Under the Bidasoa

- Eneko Aizpurua makes an exhaustive review of some recent passages in the literary essay Bidasoan gora (Elkar, 2020). I stitched the documentary work with the gaze of the walker, narrates what was seen and learned in the journey from the marsh of Txingudi to the source of Xorroxin, being always in the posterior plane the Bidasoa, in some meeting points of different, metaphor of the tragedy, in others. The women of the poxpolo factory of Irún, the police assembly of Mikel Zabraise, the murder of Eduardo López Moreno, the Lakoizketa loca, the port traffic and other stories of those who have lost on the road, have wanted to relive part of the journey.

The crossing of Endarlatsa is characterized by its literality, without the need to know the stories of Eneko Aizpurua (Lazkao, 1976) in his attempted ascension by the Bidasoa. The N-121-A road, which connects Behobia with Pamplona, becomes a bridge between Lesaka and Bera, and the one that deviates under the main bridge, in the same place where the Republican militiamen exploded to prevent the passage of the races that circulated along the Irun road during the Civil War. Next to the Bidasoa River, Aizpurua is located in the resting area next to an abandoned hydroelectric power plant. “It seems that here we immersed ourselves in another time underneath. The past is here, standing, and progress is there, at full speed, on that road that has caused so many deaths.”

Without the mist of the rivers of the morning, but as a fading, the closed gorge adds to the place a tetragic air, which will be burned by a large fire three weeks after our appointment. “Pío Baroja said that in this collado there is something perverse, terrifying,” says Aizpurua. In his words, there is no economic erudition of some amateurs of the quote, but it stitches the data of the faithful reader with the observations of the good walker, both in the book and in the interview. “V.S. I read to Naipauli that a place has no real trait, until a writer places it in a book.” A passage from the Eleven Steps of Ramón Saizarbitoria, located in the area, “not in vain” has been recalled. Writer Iñaki Abaitua and Etarra Eduardo Ortiz de Zarate park at the junction of Endarlatsa to cross the river and flee to the other side of the border. They are killed in that effort. “I think Saizarbitoria voluntarily chose to set the scene here. Because it is symbolic and also here is the tragedy, being the border between Gipuzkoa, Navarra and Lapurdi”. He points it to the other side of the bridge, where the commemoration of the 42 carabineros shot by order of the priest Santa Cruz resides.

A few meters further behind is the stone of Txapitela and, within it, the first border cairn, from which the journey of today begins. The 19th century is the treaty by which France and Spain set their limits. It specifies: From the Txapitela stone to the sea, the Bidasoa river marks the natural border and from the Txapitela stone to the interior the jones. “Bidasoa has always been a meeting point, a natural resource used by both sides for trade. This agreement uses it to separate the meeting point, making it first a ‘natural’ border and then a political border.”

.jpg)

Right to doubt

We have progressed slowly, attentive to the ground, avoiding the wells to the maximum. Aizpurua asserts the rhythm and perspective of the pedestrian as a counterpoint to the rigid world of ideas. “Many times our theories are closed constructions and clash with reality.” On the contrary, those who see, smell, hear along the way, serve him to complete prejudices, gathering the diversity that early ideas can hardly receive. After intensive documentation work, he left the Txingudi Marsh on a June 2019 day and completed his six-day tour in the Xorroxin Cascade. He didn't plan with the unforeseen of the road. The book is a rigorous treadmill, critical not only to the environment, but also to its condition: ecoobo, dominican… We could add “flâneur” if it did not exist long ago in the list of poorly used pedants. But Aizpurua's literary essay also has it. Remember how you like W.G so much. Sebalde attached great importance to walking. “Literature has the will to collect the detail, and walking is linked to it. Now, for example, we're getting to the Endarlatsa tunnel. According to the official version, Mikel Zabraise was brought here in 1985. When you walk around here, your head starts spinning; when you go to the sad road on the general road, you don’t realize that there is this tunnel here.”

In parallel to the old Bidasoa railway tunnel, Aizpurua says: “The official version is false. Mikel Zabraise was tortured in Intxaurrondo, he was given the bag and went by his hands. After his death, they had to draw to decide to which Civil Guard would take charge of the package before the courts. Once the body was moved, they began to prepare the assembly, which led him to inspect a hole that was around this tunnel and, at one point, to escape from the central opening of the tunnel to the river. He was wearing the burgundy. How was he going to escape them? He doesn't have his leg or his head. What is surprising is that Spain has not yet acknowledged what happened. The official version says he choked to death on the Bidasoa River. Family members are desperate, tried to open the case recently and were rejected again. It’s like hitting the wall over and over again.” Aizpurua still does not know, but in a few weeks there will be an audio that gathers the dialogue between the two Civil Guards and that demonstrates his thesis.

"Literature has the will to collect the detail, and walking is linked to that"

Ten years after the appearance of the Zabraise body, Spanish police Eduardo López Moreno was killed at the abandoned Civil Guard headquarters, a few meters from the Endarlatsa tunnel. While he was fishing in the Bidasoa, he came for a moment into the old barracks. There, with something strange, he began to explore an object. It broke into his hands. It was a pump placed by ETA three months earlier. They knew it hadn't exploded, but the rectifiers didn't find anything, and the question stayed there. Aizpurua recalls how the same day of the explosion the attack on José María Aznar took place. “I was in college and I remember being offered to Aznar all of Tele 5’s information. The murder of López Moreno was commented on in the last ten seconds. At that time I didn’t look at him, another police officer has been killed and ended.” During the preparation of the book he contacted his son, who knows by his mouth what they lived since the attack. From him they had to go to live in Andalusia, their mother's village. But there his son felt strange. “I was from Bera,” he said. They would take his hair and say that he was weird... That’s literally very powerful.” After fifteen years he returned to Bera. “I could follow the road calmly, looking the other way, but I wanted to pick up that diversity in the book.”

Aizpurua relates writing to the sowing of doubt and defends the right to doubt on many conflict-related issues. “It seems that many know where we came from and where we go, what had to be done before and what now. They’re always signaling the right path.” On the contrary, she has been “looking for the lost on the way”. “There were a lot of people who agreed with many of the demands from one side and with many arguments from the other, but it devoured turbulence. When the paradigm ‘with me or against me’ is imposed, many stories and experiences are on the way”. It recalls the image observed at the height of the conflict – when ETA had kidnapped the entrepreneur José María Aldaya – in front of the Good Pastor of San Sebastian: concentration on one side of the road in favor of his release and concentration of counter-concentration on the other. Between them, the passage of zebra and an old woman passing through it, pulling the food cart, looking down on the ground. “What would that woman think of what was going on?”

Risks of lost arcadia

We go back to the junction of Endarlatsa, enter the car and head towards Legasa, following the course of the river. Along the way, green meadows, small hills and bucolic landscapes of all kinds tempting for nostalgic people are opened. On the contrary, Aizpurua believes that there is nothing like looking at a river to cure melancholy. The mystification of the landscape is on the alert. “The Austrian fascists also invented a glorious past and resorted to the mythic landscape to underpin very dangerous political ideas. That wonderful Basque landscape, that bucolic green, is a lie. Beware of nostalgia and the mystification of the past, which is what causes the current nightmares.” These readings seem very interested to you, because the past, for anyone who wants to explore, has many images beyond green grasses. The poxpolo factory of Nuestra Señora del Juncal in Irún, for example. Created at the end of the 19th century with Jewish money, more than 600 women worked in very harsh conditions: phosphorus made teeth and gums. An average of 23 years, single and syndicated. They were united in Britain with those who worked like them, and they managed to improve conditions after the tough struggles. “To us comes the story of the peasant family caregiver woman, the legendary Basque Arcadia. I have nothing against the caserío – in the book caserades and mills are collected – but many times they sell us retrograde ideas in the name of the caserío”.

.jpg)

In view of the legasa, we slow down the march and turn right to the house of José María Lakoizketa. According to Aizpurua, Lakoizketa perfectly embodies lost people along the way. It was called a ‘lacquered nut’ because at all times it was seen, next to the basket, gathering weeds from the bush. He was a member of the French Botanical Association in 1877, wrote two books and formed an herbarium with 2,500 herbs. A woman appears in the lobby just before discovering what her unknown feels around her house. When he explains that we want to take a picture of the mural for a report on Lakoizketa, among others, it has disappeared at full speed and soon returns with a leaflet. “For you,” he issues Aizpurua. The Dictionary of the Basque names of medicinal plants (Dictionary of the names in Basque of medicinal plants), written by Lakoizketa in 1888, is an original copy that collects the names of medicinal plants in Spanish, French, Latin and Basque. The leaves are packed with rat knives. It presents us: Kontxi Bergara, a native of Etxalar, married to Narbarte. The socket suffers when talking about Lakoizketa, but also the illusion that someone will be oblivious. It explains the calves that have happened with the herbarium: They had it in the school of legume friars, and when they moved to Pamplona, the relatives proposed to leave it in the Lordship of Bertiz. The mayor denied them. They had to keep him in the stable of his house, wrapped in newspaper paper, until they managed to take him to the Museum of Natural Sciences of Vitoria through his family member and writer Eduardo Gil Bera. “It’s Europe’s second herbarium and think about how we’ve gone.”

The ingenious Portuguese drama

After passing the Legasa bridge, we took to the left and there is the Katxaine farmhouse, the cradle of Blas Andresena. In his book, Aizpuruak presents what the Portuguese told him that passed from 1962 to 1965 on the other side of the border. While the Franco regime prevailed in Spain, the Portuguese landscape was no better: In addition to the Salazar dictatorship, there were colonial wars in Angola and Mozambique that forced many to go to war. In addition, the country was in a severe economic crisis. In this situation, a great migratory flood crossed Spain to move to France, where there was a need for a workforce. They traveled underground, pickled in trucks to Pamplona and from there, on different roads, to the border. Andresena acted on one of these roads as a border. As he told Aizpurua, from May to November, more than 200 Portuguese were passing daily. From the area of Pamplona they were brought first until the sale of San Blas, from there to Legasa, and as they went in line through the pair of Katxaine they were given a snack, passing the bridge and from monte to monte to go to the Baztán. Thus emerged the Portuguese path, a road traveled through a place where nothing was.

Aizpurua interviewed the limiter Pierre Aprtegi for the book, who told him how he found the corpses of about ten Portuguese near his house. Asked about the total number of deaths, he replied “this is only known by the Bidasoa River.”

Aizpurua explains that a photo of the migrants left the house was divided into two to leave half and bring the other half. If they were able to reach France, they would send their half by mail to the house and the family would pay the last part to the smugglers. However, there were many who lost their way. In addition to Andrés, Aizpurua interviewed the border Pierre Aprtegi for the book, who told him how he found the corpses of about ten Portuguese people near his home. Asked about the total number of deaths, he replied “this is only known by the Bidasoa River.” More information was found in the newspaper library: News from the Basque Journal says that only in 1972 did 182 Portuguese die crossing the Bidasoa. Rosa Arburua, author of the only research work on the issue, questions this data, suggesting that it may be inflated. In any case, the generation that can testify to this tragedy will not last long, and Aizpurua is concerned that it will go unnoticed: “Today we take very much into account what happens to those who come from Africa to Irun, the media tell us what is happening in Gibraltar, and yet we know nothing about the drama that happened here just 50 years ago. We don't even look at him. Why? Because they were strangers.”

River without spring

.jpg)

To finish the tour we approached the Lordship of Bertiz. We have closed the doors of a natural park of just over twenty square kilometers, which, in addition to native species, houses over 120 exotic plants. The marriage formed by Pedro Ziga and Dorotea Fernández gave it the current form, between 1900 and 1949. High-class people, with the family, only managed the heritage. Aizpurua says that they were a “very open” partner for this time and that, for example, they had a special sensitivity for the rights of animals, languages and the environment, unlike other lords in the area. “They wanted to build an idyllic place, but is it possible?”

Ziga built a villa on Mount Aizkolegi, on the top of the manor, as a gift for his wife. There, he installed an observatory with a telescope to observe the stars. When Fernandez died, Ziga was left alone in his perfect paradise. “Among the population, I was rumored to look at that telescope more to the sky than to the beaches of Lapurdi, to see the naked women.” The last stop of today's tour lies in front of that garden of your dreams. Contrary to what many believe, the Bidasoa is not born in the waterfall of Xorroxin, which is the Baztan stream, but later, next to the Lordship of Bertiz, at the point of confluence of the waters of Zeberia with those of the Baztan stream. High, there is also a little bit in this account: “There are those who say that the Bidasoa is born in the area of Doneztebe/Santesteban when the Baztan takes the waters of Galbaiaralde.” Whatever the case, there is a clear question: Bidasoa has no springs. And on the Bidasoan pages there is also going to be one missing for the reasons of the facts. You will only have to open the book randomly to meet the uncertainty: “The more steps are taken along the road, the further the head of the river or stream in question appears. Therefore, wouldn’t it be better to slow down the step and instead of putting your eyes on your head, to quietly look at what’s in front of you?”

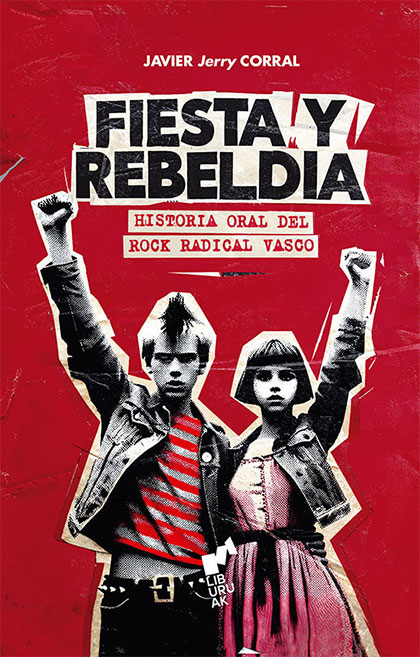

Party and recreation. Oral History of Rock Radical Vasco

Javier 'Jerry' Corral

Books, 2025

------------------------------------------------

Javier Corral ‘Jerry’ was a student of the first Journalism Promotion of the UPV, along with many other well-known names who have... [+]