Transformative Municipality

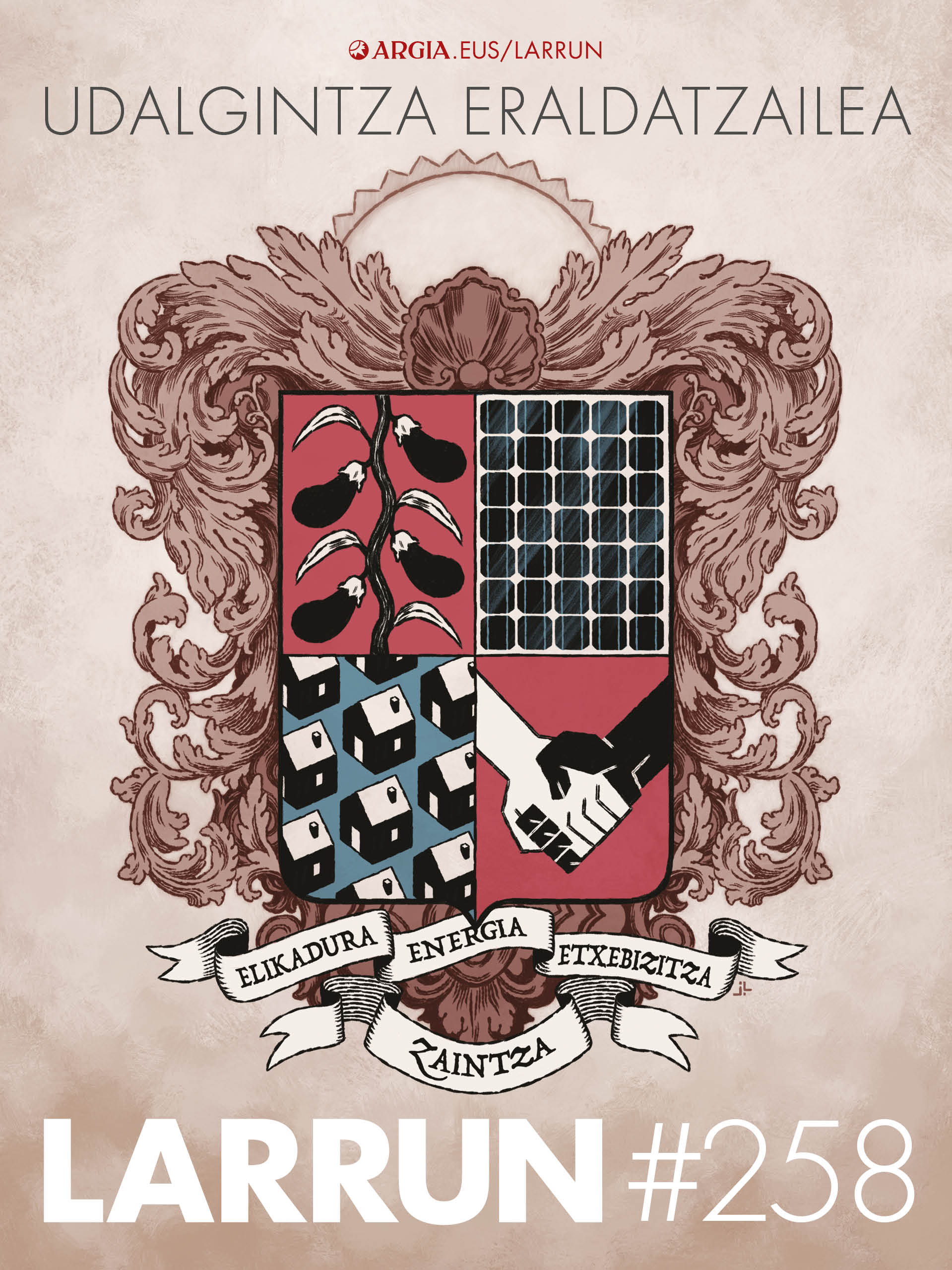

- Transformative social economy (SE) projects demonstrate in daily practice that it is possible to put values other than the accumulation of money at the centre of activities. Their networks are strengthened with the aim of increasingly endowing each phase of economic activities through ESE projects. And since that intercooperation, they've been looking through the territory, because the transformative social economy, instead of being a bubble, is a tool to transform the environment. If instead of promoting toxic activities that benefit a few in our peoples, do we devote the local economy to meeting the vital needs of the community? What if the citizens were to own the economic decisions of our environment, involved in the processes of economic activities, sovereign of our work? The transformative social economy is developing concrete proposals to present this approach in municipalities and development agencies. We address the sectors of housing, food, energy and care, priority for the sovereignty of life. Let us work in partnership between communities, municipal entities and ESE agents. There are concrete practices for this. On the road the beauty of life will flourish for all, and economic sovereignty can be won by the citizens, the peoples, the Basque Country.

Capitalism leaves more and more territories and people out of the system, emptying rural areas and pushing more and more people into unemployment or extreme precariousness. In addition, this pandemic has shown that the market does not monitor any of the activities that are precisely priorities for the maintenance of life, such as food and care.

The transformative social economy (hereafter, ESE) wants to see these spaces abandoned by capitalism as an opportunity to expand its model: in territories that are undergoing depopulation or high unemployment, and in priority sectors to maintain the sovereignty of life, such as food, energy, housing and care (including social services), to sow and cultivate an economic model based on values beyond capital accumulation.

With the aim of training and accompanying people who want to launch social economy projects, five years ago the KoopFabrika entrepreneurship programme was launched, among other agents: the transforming social economy network Olatukoop, the Gezki institute of the UPV/EHU, the Lanki research centre of Mondragon Unibertsitatea and various public institutions. Since its inception, KoopFabrika has had a territorial vision, that is, it has been aimed at integrating social economy projects into the surrounding communities and reconciling the offer of this project with the needs of the people. In these five years, KoopFabrika has helped to germinate over 80 projects, but the organizers recognize that the greatest weakness has been noted in territorialization. And to work with it, the most effective area seems to them to be the collaboration with the municipality: on the one hand, because they are the entities closest to citizenship and, on the other, because it is the municipal entities that have to respond to local needs.

What can be created if both fields are combined? That is, if the values and practices of the transformative social economy are aligned with the strategies and works of local economic development?

Current scenario: Mushrooms in municipalities, a vision of investment in development agencies

During the last ten years several collaborations have been carried out between the social economy and the municipality: the REAS network of social solidarity economy has a comprehensive and detailed approach to municipal policies and tries to present and implement them in the municipalities. In Euskal Herria there are very good local examples, but the member of Olatukoop Beñat Irasuegi has critically valued that “these are one-off initiatives, not the result of an elaborate strategy of the municipalities. What is most done is to publicize the social economy: days, training sessions... but when the municipal and development agencies plan the current and future economy of the people, they do not put the social economy at the center of the strategies”. Irasuegi also lacks the structure to weave and share experiences with these specific initiatives at the local level. The steps that have been taken in Catalonia in the last five years can be inspired by this path (see the title of Catalonia at the end of this article).

Attracting external investment has so far been the main local development strategy.

Thus, the transformative social economy proposes a new model in which the territory is a generator of wealth based on values.

This diagnosis coincides with that of Enekoitz Etxezarreta, member of the Gezki Institute of the UPV/EHU: “Until now, the strategies for promoting the local economy developed by municipalities and development agencies have been presided over by a neoliberal vision: the objective has been to create territories attractive to foreign capital, either through tax advantages, or through the construction of industrial buildings, transport networks or gigantic infrastructures such as those that were never to be used...”

In the face of this model, KoopFabrika proposes that local leaders comply with local economic development, promoting development based on the values of the social economy: local, not relocatable, that activates local endogenous forces, of egalitarian relations, of democratic management, that promotes the sovereignty of labor, that makes the distribution of wealth... the objective is that the territory go from being a container of investment to being a generator of wealth. And the most effective way to do so is to promote ESE, economic projects that translate into everyday practice values that benefit the entire territory: sovereignty, cooperation, solidarity, equality, economic justice, democracy, etc.

The ESE puts the “sustainability of life” at the heart of economic objectives, rather than a simple economic benefit. For this reason, they claim that local development should be oriented towards strengthening the productive and reproductive activities that sustain life, but not in any way: the control of economic activities should be centered on the recovery of citizenship. It would be a matter of managing the activities necessary for life locally, collectively and collectively, in a self-managed manner, empowering the communities and people who live their needs to satisfy them, making them owners and participants of the projects.

.jpg)

Transforming Municipality for the Recovery of Citizens' Decision-Making Capacity in the Economy

The term “transformative municipality” combines, on the one hand, the political and strategic practice that is fully related to the institutions and, on the other hand, the practices and values that are carried out from the transformative social economy. What is a municipal transformation needed for? Irasuegi answers this question: “Citizenship and organized actors must have a lot to say and the ability to decide what the socio-economic strategies of our territories will look like.”

The development of a transformative municipal policy requires collaboration between the three vertices of society: the community, public institutions and social economy agents. Etxezarreta explains the idea of the public-cooperative community model as follows: “The public guarantees universality, that it is a valid model for all people, that all people have the same accessibility, that the cooperative ensures that economic activity is a management model that follows the cooperative spirit, and the manifested community that gives voice and participation to that society or community in which it is inserted.” This partnership contains three key elements for sovereignty: ownership, project and participation in decisions. As Irasuegi explained, “there are ways of legally uniting the municipal administration, the users, the workers of this activity, the social agents…”. KoopFabrika is carrying out a legal analysis through jurists to make concrete tools available to the municipalities to make them aware of the legal nature through which Community public-cooperative projects can be structured.

The objective of the transformative Municipality is to manage in a local, self-organized, collective and community way the activities necessary for life

They attach great importance to organizing the community to meet the needs of their lives. Once again, containment has shown that the market does not meet the needs of life. According to social democracy, the State is the main and central facing the market, but Etxezarreta has questioned this view: “As we often see, the State can cope with the market, or vice versa, the State can be the best ally for the interests of the market. So how do you maintain the market? How can we stop the continuing expansion of the market in all areas of life? The community can be the dam of containment of capitalist logics, for the first time empowered by the community.” Irasuegi stressed that this is a "far-reaching process": “Organizing life in a cooperative and community way is not the most common thing today, it is not the trend of society, and you have to give it time, be clear on course and act, and act. The results will not be immediate, and so we have to understand it.” For this reason, he added, it is "essential" to promote processes and projects that go beyond the legislature to work with the transformative municipality and that go beyond the institutional logics.

How to approach the municipal transformative construction?

KoopFabrika, who works in the training of the citizens who will start the ESE projects, wanted to make a leap at the municipal level in the course of 2020-2021 and has organised specific training for local authority technicians and development agencies. In addition, Enekoitz Etxezarreta and Jon Morandeira, of the Gezki Institute, a member of KoopFabrika, have carried out an intense work of territorial sovereignty and municipal transformation, in which they have explained the approach of transformative municipal construction and have collected the lines of work and concrete practices that municipalities can implement. This paper proposes four lines that can be implemented by local agents who want to address the transformative municipal action.

First of all, responsible public purchasing by municipalities and the development of mechanisms for the cooperative management of municipal facilities. “Public institutions should make a special effort to channel public demand to small and medium-sized enterprises in the social economy,” they point out in this paper, recalling that there are legally several possibilities: If it is a European directive that advises the division of public contracts into more lots, this offers more opportunities for small and medium-sized enterprises to benefit from public tendering, while large companies are constrained by the advantage of the economy of scale. Another legal tool is the “reserved contract mechanism”, which establishes the obligation to reserve a percentage of the contracts of public entities to entities of the social economy. Another tool is the social clauses, which allow companies that work with principles specific to the social economy to be better valued in public competitions. There are other legal mechanisms for developing Community public-cooperative collaboration: for example, the membership of municipalities to social economy enterprises. Or, through cooperation agreements, to channel the transfer of public equipment for cooperative management: for example, to allocate public land for the development of agroecological activities or to reserve for the construction of cooperative housing.

The second line that can be worked on in municipalities is to boost employment in the social economy. To this end, it proposes several alternatives: for example, a city council can boost the networks of users or consumer groups of citizens, directing their demand to the agents of the social economy. Or it can direct the processes of recovery and transformation of companies towards formulas of social economy.

The third line is that of public subsidies, which would give economic impetus to the players in the social economy, both from a fiscal point of view and through public spending.

And the fourth line is the one that most public institutions do, but which are the “softest policies” for real transformation: initiatives to make the social economy known and visible, that is, days, constitution of sectoral tables at the municipal level, provision of advisory services, organization of social markets to articulate the sector, financing of training programs and research...

Concrete actions that may be carried out by municipalities on the basis of their purpose

In addition to the four lines that municipalities can work to address the economic transformation, Etxezarreta and Morandeira have explained in detail three intervention models that can be carried out in municipalities, proposing concrete actions for these models. Depending on their purpose, the following three intervention models are distinguished (see the title “paid, used, processed” at the end of this article): The objective of the intervention defined as “Subscriber” would be to create the right conditions for generating new social economy experiences in the territory. The objective of the intervention called “Empléate” is to respond to the needs of the territory through the formulas of social economy that are already under way. And with the intervention of “Eraldatu” the city council would become an active agent in the generation of new experiences of social economy. In this way, the strengthening of the ESE would result in the renewal of the traditional way of making public policy of the classical municipality and, ultimately, in the representation of a local development model closer to the values of the transforming social economy.

The work of Etxezarreta and Morandeira also makes a more concrete approach: they explain with concrete actions how to apply each of these three intervention models that can be carried out from municipalities in four economic sectors. These four economic sectors are strategic to ensure the sustainability of life: housing, social services (care), food and energy. The paper proposes what concrete practices the transformative city council can carry out in each of these sectors if it wants to “enrich”, “use” or “transform” the social economy.

"The real challenge is to reach the technicians and train them so that this approach is not something that one or another political color can take and take away"

Enekoitz Etxezarreta

Etxezarreta wants this tool of possible interventions to be useful to public representatives, technicians, socio-economic actors, etc. “The next step is to develop informative materials that explain these three intervention models in a simple way, and then explain them.” Olatukoop is in contact with several municipalities and with Udalbiltza to disseminate these concrete approaches (see article explaining the experience of Udalbiltza). However, Etxezarreta has assured that "the real challenge is to reach the technicians so that this is not something that one or another political color can remove and remove". In Catalonia, that is something that is very much underlined. If we come to train technicians, that is, if the technician knows what the social economy is and knows the tools that can be used at the municipal level to promote these experiences, interesting processes can be generated.” However, Etxezarreta has admitted that access to municipal technicians in this proposal “requires political will on the part of the mayor, so that municipal officials give the opportunity to social economy agents so that technicians can give these formations”. The dynamics of the development agencies are different, and they are gradually reaching out to their technicians.

You can also drive from the community and the company.

"Start with the small and the feasible is the key. Then it will join with the north and with the strategies, but it is important to start from action and think from

action” Beñat Irasuegi

In addition to municipal managers and technicians, the transformation of the local economy can be promoted by other social agents. For these processes, the work of Etxezarreta and Morandeira proposes three structural levels: the micro level would be that of companies, and the key would be for capitalist companies to make their way towards a transformative social economy. The meso level would be the articulation of cooperative ecosystems to achieve, through intercooperation, the provision of all phases of economic activity through structures of transformative social economy. And it would be a macro level to sew the network of the territory, towards models of public-cooperative community governance that meet the needs of peoples' lives. Irasuegi stressed that “starting from the small and from the feasible is the key and starting from the action”. It will then be linked to the north and strategies, but it is important to start from action and think from action.”

To undertake, in each place it can be a type of agent that acts according to the strength of each of these local agents: municipal public institutions, community and agents of the social economy. Irasuegi has provided examples of three nearby valleys, each of which is pushing an agent: “Debagoiena 2030” is underway and cooperativism has a great force in this valley, so it also has the strength to drive this process forward. In the Goierri, on the contrary, quite apart from the large cooperatives, small players and many people have gathered together in the ‘Biziola’ project. In other places it is the institutional city council that takes the initiative, for example, the municipalities of the region of Beterri-Buruntza are working on the creation of an ‘Iturola’ space in Hernani and on the elaboration of the networks and relationship strategies that are emerging around that space”. However, Irasuegi has warned that in many other territories there are no such dynamics and that their impact is strategic. Thus, the economic sovereignty of the whole of Euskal Herria would be worked with solidarity and networking.

.jpg)

CATALONIA: THREE EXAMPLES ON THE ROAD

The research of Enekoitz Etxezarreta and Jon Morandeira, members of the Gezki Institute of the UPV/EHU, gathers the path that Catalonia has traveled in the transformative municipal sector in the last 5-10 years. For this purpose, they have been based on works published by Jordi García Jané. According to García Jané, in Catalonia there have been two parallel processes: on the one hand, the internal debates of the agents responsible for local development; and, on the other, the internal debates of the agents of the social solidarity economy.

Solidarity social economy organisations were becoming increasingly clear that they had to make concrete proposals to the actors involved in local development, and the result is a 15-point proposal prepared by Xarxa de Economia Solidaria (XES) (Olatukoop has taken over the roadmap). But also other traditional sectors of less transformative cooperativism, such as the Confederation of Associated Cooperatives of Catalonia, made a proposal to co-operate the municipalities.

On the other hand, among the agents responsible for local development, the reflection developed by the professor of the University of Barcelona, Joan Subirats, was gaining strength: until then local development had been carried out without a clear direction, with the objective of generating any type of economic activity to face unemployment. In the entrepreneurship programmes that were set up to deal with unemployment, they met with the figures of the social economy.

Therefore, these two processes that were taking place within the actors of the social economy and local development were taking place at the same time and at a particular time were crossed. When? According to García Jané, the turning point occurred in the municipal elections of 2015, due to a change in the correlations of forces and a favorable situation: some municipalities remained in the hands of Comuns and other leftist parties and then began the institutionalization.

Toilets, town hall network and plan

In the organization, García Jané points out three keys: Cooperative Service Network Programme financed by the Generalitat by Labour Advisor Dolors Bassa. The Athenaeum are a public service that is based on social economy agents to generate entrepreneurship and new jobs at the regional level.

Another important key is the creation in 2017 of Xarxa de Municipis, a network in which municipalities share the practices of municipalities and define common intervention models (in France there is but in Euskal Herria there is nothing of that). In total, 32 municipalities began to be part of this network, which currently has 41 municipalities. Some of the most important initiatives they have developed jointly are the training of technicians with specific training of social economy in solidarity in the municipalities, the creation of a municipal service of social economy in solidarity as a driving entity of the municipality, the development of tools to detect, know and map the social economy in solidarity, the creation of a bank of experiences of social economy in solidarity...

And the third cornerstone is the case of the City Council of Barcelona. It established the municipal entity Comissionat, the interdepartmental, which launched the PIESS or plan to promote the social solidarity economy: This is the most ambitious plan in the Spanish State, both for its comprehensive approach, as well as for its funding and collaboration with the solidarity social economy and the City Hall.

.jpg)

FERTILISE, USE, TRANSFORM

Depending on their objective, municipalities have defined three types of interventions that can be carried out: Sovereign territory and transforming municipality of Enekoitz Etxezarreta and Jon Morandeira, members of the Gezki Institute of the UPV/EHU:

Fertilise

Objective: Create the right conditions for generating new social economy experiences.

Dimensions: Territorial diagnoses and research; mapping of social economy agents; experience bank; days of socialization of experiences; markets and fairs; empowering users of social services to collective satisfaction of particular problems; training technicians from different municipal departments; creating commissions and municipal work tables; developing appropriate regulatory frameworks to prioritize the social economy in public procurement; promoting community care networks...

Governance: Leadership belongs to municipal institutions.

Use

Objective: Use and strengthen the social economy formulas already in place to respond to the needs of the territory.

Dimensions: Promote the supply and demand of the transforming social economy. Supply support: technical support for social economy enterprises; development of tax incentives for these enterprises; development of funding lines for social economy enterprises...

Boosting demand: the transfer of municipal equipment to the service of the social economy and the transfer of public contracts to entities with a transformative social economy (creating specific social clauses and through contractual reserves).

Governance: Leadership belongs to municipal institutions.

Transform

Objective: That the City Hall be an active agent in generating new experiences of transformative social economy.

Dimensions: To offer free public programs of social and cooperative entrepreneurship in the municipalities; to activate dynamics of regularization and cooperativization of care for working people (to use cooperatives as a tool to regularize the situation of people without papers); to participate as partners in cooperatives that group users and workers...

Governance: Community public-cooperative. Structures involving three actors would be put in place to this end:

· On the one hand, the involvement of civil society or the Community network, i.e. the users of the services, both in the design and planning of the activity. Regain control of services by citizens.

· On the other hand, social economy companies would participate in the planning and management of the service. In management, we have to rely on structures that guarantee the participation of users, such as the formula of integral cooperatives, in the decision-making spaces of the users.

· Thirdly, there would be the participation of municipal institutions in all their functions: design, planning and management and control: to ensure the fulfilment of social objectives and the access of all citizens.

These Public-Cooperativiews-Community Colleges can take various legal forms.

Experiences of municipal transformation

In the following articles we have brought experiences of transformative municipal construction:

Programme Hauspotu de Udalbiltza on the road to municipal transformation

Experience in Orduña Alimentaria

Budgets and the closure of annual accounts are nothing more at this time, from the domestic economy to most of the socio-economic spaces that we share. Large companies have begun to extract calculators and implement major plans for 2025. Small and medium-sized institutions and... [+]

One of the major projects developed by Olatukoop with other actors is KoopFabrika, a programme created in 2017 with the aim of boosting social entrepreneurship and which is currently underway.

Initially, the first idea was that the cooperatives and agents that gathered around... [+]