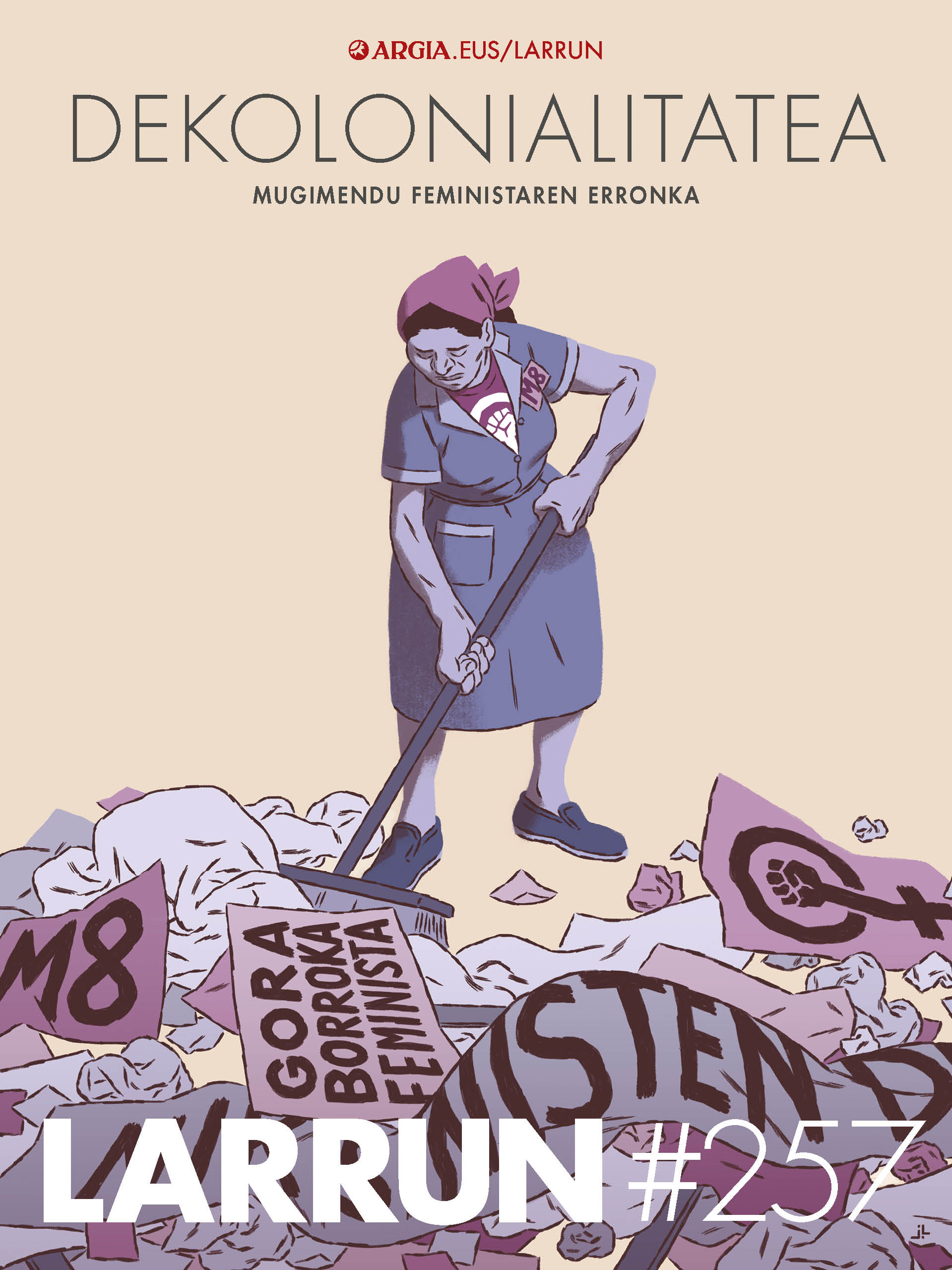

How do we free the slaughter from colonality to weave the anti-racist feminist movement?

- Decolonality, anti-racism, are not terms that were raised last night in the feminist movement of the Basque Country; on the contrary, and as the speakers on these pages nuanced, there is time for the migrant and racialized partners to question and emphasize the need for decolonial practices. In this sense, it should be understood that the V Edition of the Basque Country Championship held last November in Durango. That in the Feminist Conference a central table on decolonality has been offered. From there the reflection of the social category of race in the feminist movement was noted, and if the one who had heard did not leave anyone indifferent, the discomfort that had been accumulating in the environment became suffocating when the racist aggression that took place after a round table was known. Evidently, one of the household occupations for the future was the richest, if one really wanted to accommodate diversity. “Together we can, but decolonized,” they put the condition of moving forward from the decolonial table.

A year after the conference, and after having had time to stabilize the barriers and analyze the feelings of then, we have met with five members of the feminist movement to continue talking about the issue. We’ve met at the Deusto Youth Venue to talk about how the road to decolonial feminism is being and how it should be in the future. They say that we are at the beginning of a process and that the notebook is halfway, but from the work done so far by each of them they have drawn up some points in the roadmap that must be followed to weave feminism that will not be colonial and that puts anti-racism at the centre of their agenda.

RAPPORTEURS:

Cony Carranza Castro

Santana, El Salvador, 1963. He has lived in Euskal Herria since 2004, and as far as the feminist field is concerned, he says that he was received by the Babel eta Garaipen groups of Munduko Emakumeak. He continues to work on them today, and participated in the V Edition of the Bertsolaris Championship of the Basque Country on behalf of Garaipen. Round table on Decolonality in the Feminist Conference.

She's a calling educator, but she's been on call here. He has recently been awarded the Emakunde Prize for Equality 2019 and has used the award as a speaker to denounce the following: The Aliens Act and social racism reduce the employment of migrant women in domestic and care work.

Afaf El Haloui

Sale, Morocco, 1977. He arrived in the Basque Country in 2012 and became part of Munduko Emakumeak Babel. He says that he experienced the first process of personal and collective empowerment. It has also gone through other groups until in 2014 it decided to create the Brotherhood, with the idea that its process could serve another as a model of integration. Ahizpatasuna is a sociocultural association that brings together Moroccan and indigenous women, and on his behalf he participated in the V Edition of the Basque Country Empowerment Fair. Round table on Decolonality in the Feminist Conference.

Emilia Larrondo de Martino

Puebla, Mexico, 1983. He arrived in the Basque Country in 2017 with a teacher scholarship. She started her career in feminism in her homeland, and she's been happy because when she came here, the World Woman met Babel. He participated as spokesperson for the group at the 5th National Congress of Collectivities of the Basque Country. Round table on Decolonality in the Feminist Conference.

In Mexico, I worked at the university. Once here, he has had to leave the university's work behind with the exhaustion of the scholarship and dedicate himself to other precarious works. “You realize that not being born here puts you in another position,” he says.

Naia Torrealdai Mandaluniz

Gernika, 1992. She has been a member of Bilgune Feminist for five years. He explains that over the years of the institution the triple oppression – gender, class and popular repression – has had a constant presence, and from this ideological base a permanent rethinking has been made. Since a couple of years ago the issue of race and decolonial practices within the feminist movement has been on the table, work is being done in this regard.

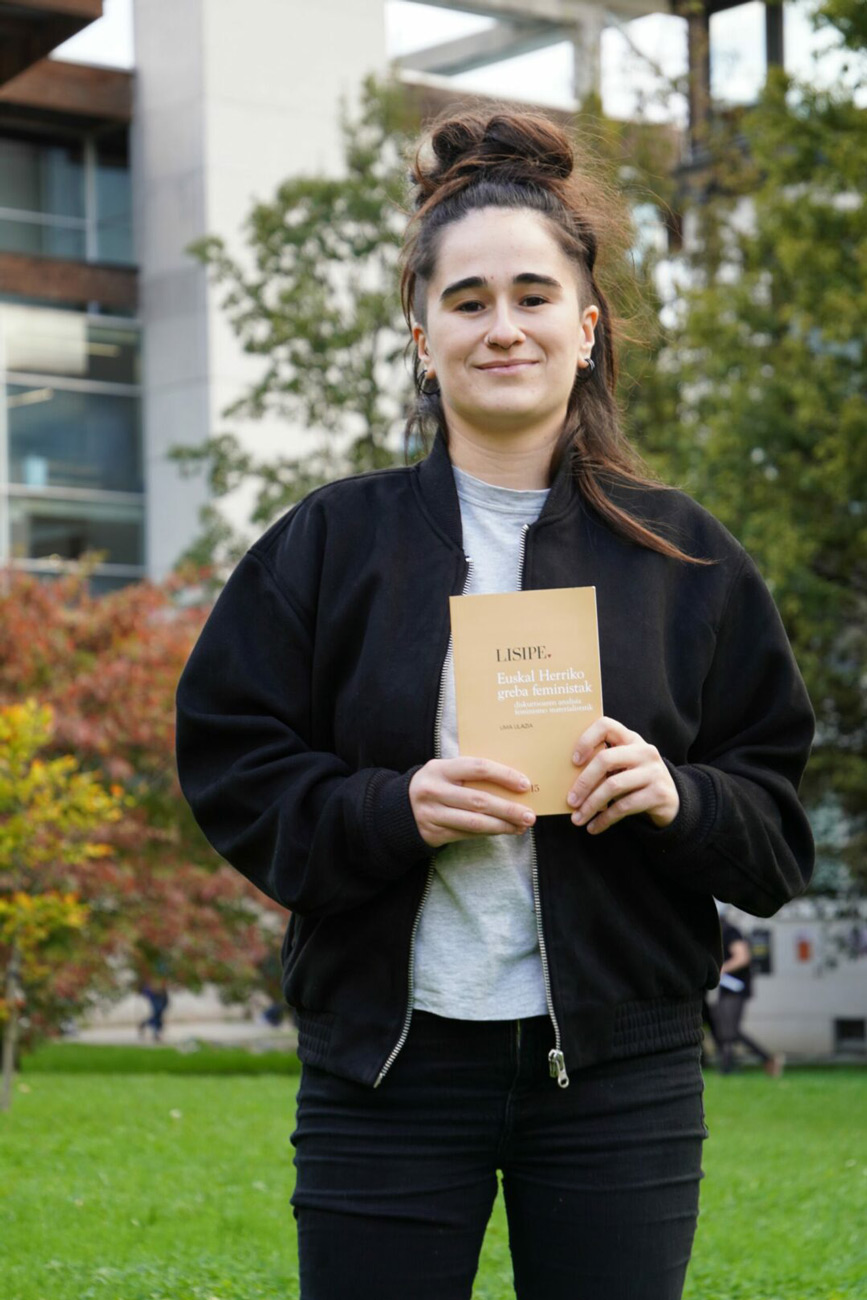

Garazi Goienetxea Díez

Santurtzi, 1990. He joined the militancy in the university era, amid the feminist struggle. However, he says that in 2014 he made a more conscious penetration of feminist consciousness, when the feminist group Marimatraka was created in the people. Since then, it has “shook its nose” in various feminist processes, and thus it has reached the World Women’s March. He has stated that he is very happy to find this space and is very keen on the process of returning from decolonality.

A year ago, the feminist days of Durango were held, in which it was found that decoloniality was one of the main challenges in the shared agenda of the Feminist Movement of Euskal Herria. What is the work that each of you has done in this regard during the time that has passed?

Garazi Goienetxea: Following the book on the days that will be published recently, in the previous edition I was reviewing the work we have done. Looking at the things that I wrote a year ago, more than once I thought that what I wrote on that occasion I would say now in a different way. There is a reflection of what we are doing.

At the Women's World March of the Basque Country (EMM) we began an interesting process. The Fifth World Women ' s March has been celebrated throughout the year. International Action, but because of the shock and pandemic we were experiencing, we decided to postpone it until recently in the Basque Country. Transnational corporations, migrations and borders are the subject of action, and as we have approached, we have realized that not all EMM members are crossing us in the same way, in that sense the exercise of paying attention is being as nice as it is hard. In short, and to give you an idea of how the process is going: in the team that drives action we are all white except one, there is only one person who has migrated, if we take into account where we are looking at the subject with all its influence. It is so true that when we were working on the issues the bridge came out as a symbol, understanding that it is something that unites and communicates; but when we shared the work we did about the bridge with the migrated women, it was very much problematized. In fact, from where you look, the bridge can also be the border, which allows the passage of goods, but not of several people. All of a sudden, there was a lot to go into. We've been exploring around, and thanks to the reflection and work of the migrated and racist members of the feminist and anti-racist movement, we began a process that was closer to dialogue than to dialogue.

They've opened up to us a world -- at least I've lived it -- a new way or logic of understanding, which gives some keys to when we talk about privilege, when we talk about how this system is built.

Emilia Larrondo: I didn't know the Feminist Days, it was unprecedented, and I couldn't imagine or imagine what I found in Durango. I participated in it on behalf of Women of the World Babel (MEB) and to prepare for such participation we carried out a work in which we asked ourselves what the privileges were passed on to us. Because SEM is a mixed group* in which the contrast between indigenous women and those who have come from outside is clearly reflected. Although there is also diversity in these two groups: among the indigenous women there are precarious jobs, with decent work, which correspond to the normative sexual norm and not, which know what it is to live in the countryside and live only in the city; and among the migrated women, diversity prevails, not only with respect to their countries of origin, but because each one has a history with it. Contextualizing all this diversity is quite problematic, it has implications, but at the end of the days we put more emphasis on it, it served as an excuse to work in this line. Because it is difficult to maintain and deepen the subject, as it involves touching many sensitive things. Although the work we have done so far is not very thick, we have begun to make the way. I think it's the beginning of something.

I would say that the work has been done in two areas: inwards and outwards. Meanwhile, we have begun to speak and define what are the oppressions or experiences that have marked us, showing different pains. In this task and among migrated women, sometimes it seems that there is a kind of competence to demonstrate a higher level of suffering, and that is very good, but we also have to work it, because it is not healthy to stay there. Therefore, the question is how we can move from those pains to obtaining tools that allow us to heal, taking us beyond the personal and taking advantage to network with other women. Isn't that? Pain must be cured, because sometimes it is pain that makes the person meet and makes dialogue difficult.

Emilia Larrondo: "The difference between us, actually, is what the system produces, and he crosses us all, even if it's done at different levels."

Work has also been done abroad, with other groups, conducting workshops that enable dialogue between migrant and indigenous women. I have not been to many of them, but, as has been shared in the assemblies, the experiences have led to confrontations with oneself and to other realities. In this regard, I remember how a person who was talking to a trade unionist friend, a woman who was very old and who worked as a cleanser, who apparently had been working on this work for about thirty years and never had a free weekend, told me. I asked my friend where I was from, and I was amazed at what he said to me: the woman was from there. I mean, sometimes in our imagination we don't imagine that indigenous women can be in exploitative situations like that. That is why I believe it is a challenge to avoid being locked within the limits of one's own experience, to have at hand the paths that make it possible. We have tried to create the two work spaces cited in order to share experiences and look beyond them to observe what we could have in common. Because the difference between us, actually, is the system that provokes, and he crosses us all, even if it's done at different levels.

Afaf El Haloui: Soon after the end of the conference, the organizational work began on March 8, and the initiative to form the anti-racist axis was put on the table. Fraternity took part in it and I noticed that there was a kind of impatience and a desire to let go of what we're inside. The fact is, there were clashes between us. There was something similar to competition, a desire to be a protagonist or, so to speak, to make the voice of oneself heard. This is the first time I have spoken publicly about what happened on the anti-racist axis on 8 March, and it has not yet come to light. It was a kind of cry, and we were left with the pain that caused us, incapable of redirecting the feeling, as the confinement was established after March 8. From there, serious problems arose such as police violence, economic problems or chauvinist violence. We got to work on that line, more than anything.

.jpg)

Poverty, rent-related problems, problems with Lanbide, machista violence… in Ahizpatasuna we have been mainly concerned with responding to these kinds of demands. With so many injustices that we suffer as a community and the demands that come upon us in relation to them, we have not been able to do the work that other feminist days demand. The work demanded by the days was great and learned. So when the days came, we thought to ourselves: “What do we have to bring to light? What do we have to say?” We try to make visible the diversity of Arab Muslim and non-Muslim feminism, to show that not all of us have the same discourse and that within them there are many contradictory realities. We've already begun to work a little bit on feminism, including Muslim and non-Muslim feminisms, Amazigh and Magrebis. But, as has been said, we have been dealing mainly with the needs of every day, such as the economic needs.

Naia Torrealdai: In the days of Durango, we were questioned as white European citizens, questioned as Basques, and there was conflict. According to the reading we have made from Bilgune Feminist (BF), interpellation and conflict are not bad in themselves, and that can be enriching as well. For us, therefore, the first step is to listen to everything that emerged, to make an active listening, and then to analyze what has been heard and take responsibility for it. Listen actively, everything that was said without homogenization, because there is a tendency to say “we were told from the decolonial table…”. But at that table, very different things were said, and we are interested in taking up those different perspectives. This last year we have heard more than read it.

At BF, we have created different spaces to work on racism that we reproduce at the individual, social and institutional levels. We want to look at what we can change. For us, practice is very important, in addition to the theory that we must assimilate. In other words, how can we put all this into practice? And in this sense, for us, the Abertzales Women’s Meetings that we will be holding in December will be very important. In time we saw more back that we had to talk about what was happening in the feminist movement, that we had to analyze how the racial axis can be placed in our political project and update our gaze. The exercise we want to carry out is as follows: on the one hand, from our position of oppressive bumpers, to work our responsibilities and privileges; and on the other, to see how we can demolish our experiences, experiences and oppression in such a diverse feminist movement. For us, it is necessary to continue sewing shared processes.

A. El Haloui: I liked one thing he said and I would like to underline it. The table of the decolony of the days was not homogeneous. It is called a “decolonial table”, but each group and community in which it was represented has different demands and an understanding of feminism.

The topic of decoloniality was the one that generated the greatest discomfort in the days. Cony, in the interview you dedicated to ARGIA in those days, commented that this unease and pain could be a turning point, if it allowed us to make our own feelings, accept them. Looking back at the current context, do you think that that inflection has occurred or that the seed is being gestated to give that inflection? What have we done or are we doing with discomforts?

Cony Carranza: I've had different sensations. I would say that some people want to think again about the issue and pick up answers, and for the time being I think they will become experts in decolonality. It's OK to read, but what we want at MEB is to land all of that, to do anti-racist practices. I have also seen colleagues who are hurt, who feel that their solidarity has been called into question. I would say that we are not questioning the solidarity of these close members, but how can we make them understand that it is a denunciation that is made by looking at a more macro level and that we want by our side? I believe that some have gone back and are not as willing as before. In the face of something that harms us, we have different ways of responding: either we don't want to join, or we separate, or we come together to make way for our anger. I don't want to think it's a burden, I want to see it as an opportunity, and also what we need. We need plurality of voices, diversity of ways of being. And today more than ever, feminism has to be anti-racist, because the indentation of our peoples, the expoliation … needs us all and all, because we need the commitment of all and all. I think we have to calm down, but I want to believe that we are doing well in the search for answers. And those who want to stay by our side will stay.

A while ago, following a reflection we made among feminist members, we were told to Latinos that we were not feminists, that we still needed to become feminists, and someone said: “Well, we’re going to go up to the top and see if we meet.” And I say that this time it won't be that way. On this occasion, we will make the way together, well looking for paths together.

.jpg)

R. Larrondo: To what Cony said, I would add that we will meet women who are willing to review themselves, understanding that we are also among them. Because although we are part of the collective of migrated and/or racialized women, we also experience different inequalities. That is to say, it is not a matter of passing the ball by saying to the neighbor “check you!” You have to look at yourself, knowing that we're not all in the same situation, that's it.

A. El Haloui: I say that it is still too early to draw conclusions, too early to be able to say whether or not a turning point has been made. Let's be honest: we've only made a diagnosis of the disease. Much work remains to be done and the land is not yet cultivated. What we have to do is go and work that land and "when?" Answer questions like “how?”

Afaf El Haloui: "Let's be honest: the only thing we've done is to diagnose the disease. Much work remains to be done and the land is not yet cultivated"

N. Torrealdai: I would like to add that in the days of Durango the conflict was made visible by the participation of more than 3,000 women, who were broadcast on television, who had presence in the media. But I think it should be emphasized that this knot comes from years ago within the feminist movement of the Basque Country. It seems to me that we have to think about it, because otherwise it seems that the subject suddenly appeared, a year ago. For us, EMM is the space that made that interpellation and highlighted the need for decolonial practices, and now I mean several years. I think there is a need for recognition. This issue was also in the heads of militants of the feminist movement.

R. Larrondo: Maybe all of that was catalyzed in the days, right? Because I think it was a Molotoff cocktail that fell unexpectedly.

N. Torrealdai: Yes… but it seemed that the anti-racist movement, the migrated and racialized women had just reached the feminist movement through these days. And that's a lie. We've been finding ourselves in different spaces.

R. Larrondo: What I believe is that they have not had a voice, or simply a table made up of them.

N. Torrealdai: Yes, of course. That was historic. It was the first decolonial table.

R. Larrondo: That says a great deal, because that is the fruit of all that pre-debate that you mentioned, right? A specific table was set up to deal with these issues.

Continuing with what was said in Durango, aware that universalizing and homogenizing is colonizing, it was also clear that the subject of the Feminist Movement of HD must be plural and inclusive. The point is that, although diversity is often given a joyful character, as Itziar Gandarias said, it has a close relationship with conflicts, with discrepancies, with disputes. And so we have to work the closeness, but we also have to manage the distances. How is balance maintained?

The great C. Carranza: As Gandarias says, we have to work on diversity. I still don't know where we're going, I'm like in the middle of the fog. But I do believe that, as has been said, we need active listening. We cannot be afraid of meeting, of continuing to question, of continuing to seek anti-racist practices. And if whites want to be there, they can do it, with some things that at first glance don't seem so important: getting marriage papers with someone, offering help to get hire or registration -- they can help with a thousand. If you like, you can find those little things. But that's what requires feminist and anti-racist listening and gaze.

We have a notebook full of white leaves to keep working, learning from other experiences. I'm hopeful, I think it's possible to build something.

A. El Haloui: On the road taken by Cony, I too regard the support and complicity of everyday life as important. Whether it's the census, the rental or the papele -- it's OK to be there. But not from tutoring, it is also important to underline it. It's OK to be there, but keep going over yourself and privilege. If you do these things day by day, and you have to do them, they're tasks, we can talk about solidarity between women. In this solidarity, the keys are the abandonment of tutorials, the reduction of the gap between them.

In addition, when we meet and give our perspectives on feminism, it is necessary to give voice and make active listening. Much remains to be done.

R. Larrondo: I liked, Afaf, to raise certain issues properly. There are different levels of privilege, both indigenous and migrant. And the exercise of certain actions from the place that privileges grant to one, often does not condition that privilege and, at the same time, contributes to reducing the existing gap with that other person. In addition, the assignment of spaces is one of the tasks.

There are many things that can be done on a day-to-day basis, and then we have a political agenda, that is where we have to explain the problems. I think we have to act on those two levels, the macro and the micro, and that can guide us to other practices. Although I believe that total change is long-term, some changes that can occur in daily life can lead to a 360 change in the lives of people who are migrated and racialized.

.jpg)

N. Torrealdai: I think one of the keys is mutual recognition and empathy. Because in the days there was a time when there was a feeling that you created an artificial. There are different positions between us, both between migrating and racializing and among the indigenous. Because after all, gender is not a universal experience. The first challenge would be there: in visualizing and defining those positions. And in that sense, we believe that there is still work to be done as far as power relations are concerned. And then decolonial practices, which should be terrified and settled, build community and weave practices from day to day, should be promoted. All this, as it could not be otherwise, without falling into tutorials.

These are issues that move within, and there is obviously resistance. In this regard, I believe that we must look responsibly at these resistances. Accept that they are there and think about what to do with them, how to turn them around and implement anti-racist and decolonial practices. And there, I think the key is to build trust. And it's that it's real experiences of coexistence that are going to allow us to make our way. This includes the realization of decolonial practices, the search for solutions to everyday material needs. Like Cony, I think in Euskal Herria we have the opportunity to create something, and those keys can help us.

Naia Torrealdai: "Resistance must be looked at responsibly. Accept that they are there and think about what to do with them, how to turn them around and implement anti-racist and decolonial practices"

Dr. G. Goienetxea: I would like to add an account. In our imagination we represent diversity in a way, but then in reality the landscape is different: power relations, structures… diversity is lived and embodied like this. In this way, and taking into account the words of Angela Davis, I would like to stress that the anti-racist struggle must be at the heart of the feminist struggle. Maybe that's what can make them come closer and make diversity more and more similar.

A. El Haloui: We ask about distances and approximations, and we turn to cracks. This has one reason: in the cracks is what can make us closeness. Once the gaps are removed, we will be able to build approximations in place. Because if you don't work inequalities, there's no closeness.

Dr. G. Goienetxea: So I think it's important to bring anti-racist struggle to the feminist agenda and work from there. Let us not take the law of foreigners, let us scream against it, and let us leave this, on the periphery, because it has no centrality in the agenda of our political project.

R. Larrondo: This also came to light in the OVM: instrumentalization of migrated women, going to an action as a representation fee, more than anything. Here it is a question of materializing this representation so that there are improvements in personal or collective life.

Speaking of distance and closeness… Can the existence of mixed and non-mixed spaces be the calibrator of this balance? What do you read about each of these spaces?

The great C. Carranza: I myself, both at MEB and Garaipen, work with indigenous women. Of course, most of them are women willing to go down this road. But the truth is, those spaces are bubbles. You go out to reality and it's terrible. I also have this voice, this skin color, these factions -- I'm reasoned. It is hard to put into words all that everyday racism means. However, as we said as Victoria, we are in favor of mixed spaces. Always respecting people who want to stay in their own room. Since we began to build the classrooms of the SEM, ours and the women of the area, we want to continue with them. So I don't want to question a group like Razes. Where do you want to flush? They will do their work and their way, and it will be beautiful if they ever want to make another thought. What's more, I think they're doing it. I have a lot of respect for those who don't want to be in mixed spaces, but I, for today, want to be in mixed spaces. With the women who want to undo and transform, and I in the spirit of continually transforming.

Afaf El Haloui: "What can make us closer is in the cracks. Once the gaps are removed, we will be able to build closeness in place"

A. El Haloui: I agree with Cony: you need to be in mixed spaces. On the contrary, it will be impossible to boost the change we want to make. Because non-mixed spaces offer ghettos to us, they take us out of different fields of oppression… but they are also a way of being angry. And anger leads to hatred and hatred for separation. I myself, and also Brotherhood, are in favor of mixed spaces. As we have said before: no mentorship, because it is about protecting and helping the next one, not victimizing. If we are going to work with you and migrate together, we have to take care of these aspects, work inwards. There will certainly be clashes, but there will be conflicts that will reach some port. I believe that without going through these conflicts there will be no change. However, if there are mixed groups that are so angry, it's for something. And if you have to protect them. But I think you have to be in mixed groups.

R. Larrondo: I would say, in short, that they are not mutually exclusive. It is possible that a certain group of a group may at some point need their own space. But if an interview is not then given on what has been worked on in the non-mixed group, it is difficult to contrast it. And you get tangled up in that one speech. Therefore, I believe that they are not mutually exclusive, each space has its moment and responds to different needs, but I believe that the combination of both is important.

Dr. G. Goienetxea: As a white woman, I find it hard to pronounce my opinion. But I say that if there is a need to create non-mixed spaces, it will be for something. The analysis I do is limited to comparing as a woman with what I have done. I belong to a feminist group that does not accept any man and that has its reason to be non-mixed. In cases where race is among them, I think it is the same. This example is the one I use as a mirror. And I think they're not mutually exclusive.

On the other hand, I am very grateful to be able to participate personally in mixed spaces. I confess I need them. Although I frequently ask questions that I may not ask the migrated members, it is up to me to work mine. Someone will send me to the devil one of these days because I always get cotton from antipathy or decolonality. Because that too happens.

.jpg)

N. Torrealdai: I think it's not up to BF to talk about this. It is up to us to listen to the debates that migrant and racialized members have, they are the ones who have to talk about how to organize the anti-racist and feminist struggle.

R. Larrondo: I'm going to put my finger in there. I had the opportunity to attend a session of intercultural dialogue and I found it very interesting, as there were many stereotypes of indigenous women that we had the migrated people and vice versa. Sharing was great. It was very hard to hear what had been published. The session was not perhaps a feminist group that has done a lot of work, it was normal women, but I still believe that those of us who have worked on some issues also reproduce those ideas. That is why I think it would be good if women here also had room to talk about what the presence of women from outside in their communities has meant for them. It may not be politically correct to talk about it, but they are things that are there and that would be OK to talk about.

The great C. Carranza: At this sitting, the closure was important, as it became clear that similar issues are going through us. Similar fears were expressed: loneliness, decay, sadness…

R. Larrondo: Finding those common points is what will strengthen us as a collective. And that doesn't mean hiding the differences. If we're here making this effort, it's because there's a lot going through all of us. I believe that to build bridges between them it is important to listen, respect and build.

The others, how do you think they should be bridges to each other?

The great C. Carranza: We tell men to take a step backwards, for here the same thing. Easy, right? Tell me more, allocate more time... you now have to put yourself behind, or next door, but not later. Along with this we have to listen, without judging, because the truth is very well composed and while the colleague is talking we are working on the answer. It is not an easy practice. We have to review it and let others do it without being on the front line.

N. Torrealdai: I believe that we, individually, must ask ourselves what it means to occupy a hegemonic position. And we have to ask ourselves how I can withdraw from it. Likewise, in the case of BF, it seems important to think about the ways to bring to feminism the topic of popular oppression. In this regard, and in connection with what Afaf said earlier about language, I believe it is up to us to demand linguistic policies that go beyond putting the Basque country at the centre of a Spanish system and that are accessible to all. Because a person who is poor in time and material does not have access to the minimums of the process of Euskaldunization.

As for what affects us, we see a need for a bilateral process: to review our history – to observe what the patriarchal pacts that have been given in Euskal Herria with the implementation of modernity have been – to analyze the role of the Basque explorers in the era of colonization in Latin America and Africa, and to see what the responsibility we have in this regard – and also to specify what responsibilities we must demand. And finally, what for us would be key: to think together how we are going to build a feminist Basque Country, with a shared agenda, and to reflect on how we are going to jointly propose transformative practices.

The great C. Carranza: I would like to point out that we have to go back a lot. Because the step back has to do with rhythms, spaces -- everything. Because you have already established a meeting model that destroys us. Whites have a wealth of time to lengthen the meetings, and we have some strength, but you also do those agendas… and do not realize what we are talking about when we say that we have to reflect on taking a step back. It's not just a step backwards in the demonstration. Without idealizing anything, but learning another rhythm of life comes from South America. We have to pay attention to other looks, to the most localized forms of work they have in Africa and South America. When I got here, my mother would tell me: “But what happened to you? Always running, thinking about time.” And that affects everything. And so, each one of us reacts in itself, because we don't get there. You can't stop there. The models of meetings must be broken.

As we saw in Durango, the fact of talking about (de)colonality makes it compare with the oppression of this people. How do the two processes intersect?

R. Larrondo: I think it is important to talk about this, because I think it is two different processes that cannot be compared. Without any intention of belittling the oppression suffered by Euskal Herria. It seems to me that the colonization of South America, which differs from the colonizations of Africa and Asia, was a milestone. This allowed it as a racial category; before, people differed according to factions, but this differentiation acquired another force through the colonization of South America. I believe that at this turning point this capitalist system was inaugurated, which has as its axis the differences between women and men, which determines who has access to resources, and also what distinguishes by race. As a result of colonization, people ' s experience is permeated by mass rape, exploitation, non-discrimination murder, the experience of the people who lost representation and became a small percentage, a process that is still in progress in a different way. That experience, in itself, I do not think is of the same significance as that of the Basque Country. That is, the oppression that has taken place here, looking at the world, has not had the same influence as the conquest of Abya Yala. What I mean by this is that colonization was fundamental to building the world we know today, and that can't be compared to other processes. I think it is healthy to have the differences clear, without subtracting a single gram of pain from the experience of Euskal Herria.

N. Torrealdai: For us this is the main question. Clearly, I have no answer for the moment. One of the questions to ask for BF is: What kind of approach can we make to popular oppression from the practices and theories proposed by decolonial? Because when we talk about an era of expropriation in Europe, we lack a word to talk about what this people has suffered. And it doesn't have to be colonization, I'm not going to go around. But we need to review our memory, because when we talk about epistemicide, we connect it with language, with ways of thinking, with ways of doing, with our land, with witch hunting..

We are in a two-way process: from the point of view of race, privilege -- we must reinvent ourselves and, from that decolonial perspective, make a review of our memory and our history. It is important for us to carry out this review, and its ultimate objective is to develop a political project, located in the Basque Country, that is liberating and allows us to be sovereign. And along with this, the constitution of a Basque feminist community that makes demands and demands visible at the structural level. All of this, of course, must be done by avoiding comparisons. For I will never know what it is to go through the experience of another like, as he does not know what it is to live what I have lived.

Garazi Goienetxea: "It seems to me that decolonial reflections make us a mirror in which we reflect something that we have not worked on. And it makes me uncomfortable when you put in that mirror that we use the wild of popular oppression."

Dr. G. Goienetxea: To contribute to the debate, and based on how I have lived on a personal level, I will say that this issue causes me discomfort. What a coincidence? Who not? It makes me uncomfortable because it seems to me that decolonial reflections make us a mirror, reflecting something we haven't worked on. And it makes me uncomfortable when you put in that mirror that we use the wild of popular oppression. What brings me outrage or discomfort is that when we look at the point that our colleagues point to us, we look at something else, not all the anti-racist work that we have to do. In the days, in my opinion, it was our duty to keep quiet about what we said at the decolony table.

N. Torrealdai: I totally agree.

R. Larrondo: But what happened is a good sample.

Dr. G. Goienetxea: Well. The point is that sometimes we have to decide what to give priority to, because not everything is on the agenda. So what really needs to be put at the center? I am very clear: anti-racism. We also have a lot of work to do, but right now I think that's one of the challenges: putting anti-racism at the center.

R. Larrondo: Going back to the beginning, and to make it a little clearer what the process distinguishes between one and the other, the key may be to compare the current situation in each of these territories. Differentiate what is happening in the global South and the global North. Because the expropriatory processes initiated in times of colonialism remain in place, and it is so true that one cannot compare, or at a distance, the quality of life of one another. I think the key is to look at what the current geopolitical role of each territory is, to understand the differences between oppression and colonization.

A. El Haloui: I would say that when these kinds of issues are put on the table, we are very far away. As for the problems, we also have cracks. We are also moved by this topic, we also have a history of our own colonization, the culture that tarnished us and other realities and ways of life that imposed us, oppressors too. Colonization impoverished us. But today, attention is focused on everyday vulnerabilities; we don't know how to get out of those situations, so how are we going to question such profound questions? And I say this, let us understand that around a table that brings together different groups and that we have called “decolonial”, there are different priorities among the problems.

What are the challenges for the future? What are the strengths and the obstacles?

The great C. Carranza: I was drawn away from being part of what I doubt. I'm dedicated to caring for migrated women, but I haven't yet found a way to meet those women I work with, to see if I meet them through popular education. I don’t want to think I crush, but I have to keep checking to see how I develop the conversation, how I create closeness, how I listen… so I don’t victimize, so I don’t become paternalistic. It feeds me to hear myself, because at the moment I feel like I'm part of this Western world. And I from this north want to build the reflections of the south.

N. Torrealdai: Making a positive contribution, I would say that I believe we have strengths: we have a self-critical feminist movement, which is not afraid to talk about these issues, even if they are so theoretical and abstract. And I also think we have to recognize ourselves, because we've been on the road for some time and we're still on the road, in the different spaces that we find ourselves in.

As for the challenges, I have one identified: to see if we can speak and discuss without measuring the oppressions, from mutual recognition. Because it seems to me that in recent years there has been a tendency to question the center; Basques, racialized, chaplain, trans, rural… everyone has questioned the hegemonic feminism. But the question is: Who's in that center? I think one of the challenges would be to work on that point together. Because the retreat from the center is not only to leave the space, but also to build spaces for critical debate. I think the role of those of us who are in a more privileged position and those of us with the most resources is to create those spaces. There we have work to do. And with all of this, of course, we have to keep coming out against our enemies and monsters in common, that we are increasingly in more vulnerable situations. For me, the ultimate goal, in addition to doing theoretical work, is to continue to make a path.

A. El Haloui: Yes, we have to create spaces without labels. And in them we will have to take care of the rhythms and vulnerabilities of some: how will there come those who do not have enough to pay for transportation, how to allow the presence of children… there are many things to take care of.

R. Larrondo: I'd like to get back to something that was talked about during the interview: that of mutual recognition and empathy, and to work honestly with yourself. Because we are not of a single dimension; on the contrary, we fill in the roles of victim and victim depending on the situation. We have to be aware of it and get closer from respect and listening, seeking to share and understand the following. After all, as has been said, we have things in common. We have to be clear about what they are in order to move forward. Because I think many times we lose ourselves in the grandeur of all that the oppression that we live as women, or other identities that come across us, entails.

On the other hand, there is also the question of reparation. When we talk about bridging the gap caused by inequalities and changing reality, it is all very well to denounce and point out how these inequalities are constructed in daily life and what their consequences are in daily life: oppression and privilege. But once this awareness has been internalized, we have to take positions and demand repair. In other words, we must not only talk about ending colonization, but also about the remedial measures that we can use to bridge the gap in inequalities between the global South and the global North.

It seems to me that we have to see and rescue the beautiful parties, because we have taken enormous steps. We should balance the challenges and what we have achieved so far to moralize ourselves. I think it is important.

Istorioetan murgildu eta munduak eraikitzea gustuko du Iosune de Goñi García argazkilari, idazle eta itzultzaileak (Burlata, Nafarroa, 1993). Zaurietatik, gorputzetik eta minetik sortzen du askotan. Desgaitua eta gaixo kronikoa da, eta artea erabiltzen du... [+]

This wedge that the announcement on the radio Euskadi to replace the bathtub with a shower encourages the commencement of the works in the bathroom of the house. A simple work, a small investiture and a great change are announced. There has been a shift in toilet trends and a... [+]

Zalantza asko izan ditut, meloia ireki ala ez. Ausartuko naiz, zer demontre! Aspaldian buruan dudan gogoeta jarri nahi dut mahai gainean: ez da justua erditu den emakumearen eta beste gurasoaren baimen-iraupena bera izatea. Hobeto esanda, baimen-denbora bera izanda ere, ez... [+]