Pasta and monopoly

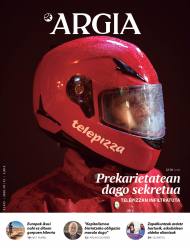

- In May of this year I published an article entitled Glovolization: I spent three months as a distributor for Glovo, to investigate the working conditions of the workers. For the most part, I only received positive answers about the article, both from the readers and colleagues of Glovo (which the company calls riders). Most of Glovo's dealers felt as exploited as they were marginalized, and readers, above all, wanted to see how one of the most modern forms of exploitation works today. However, there was a small exception. A Rider contacted me and complained that I was discovering the fake appearance of the company. He said that there is a lot of precarious work in the sector, for example in Telepizza. In short, I thought Glovo's critique was becoming fashionable. He wrote that he was working for Glovo (who had never heard of a single rider I interviewed) and also, if there are many companies that mistreat the workers, why do you have so much concern with Glovo? However, in addition to using that old fallacy (in English whataboutism) to justify the exploitation of Glovo, that person had a clear reason: criticizing this company is easy for the media. On the contrary, talking about traditional forms of precariousness is not so exciting or has the freshness of new things. So I started working at Telepizza. Here's what I found.

Getting a job at Telepizza was a very easy task. I was called immediately after filling in the Internet request. They asked me if I had a driver's license and when I could start working. A few days later, I was hired and sent to an intensive course. There they explained to me how to use yoga to manage work stress and that it is better not to face armed robbers. After I had received all my training, I signed a fixed contract, helped a colleague in a couple of shipments, and started on my own. The process that I lived with Glovo was very similar, except for one thing: when I asked if I would charge my time at work, the manager, excelled, gave me the following answer: “While you’re here we pay you.”

Some aspects of the work had obvious differences with respect to Glovo, did not have permission to smoke at work (irrationally, the most suffocating of the whole experience). I had to wear a poor quality uniform, I didn't have a zipper in my pockets, and when I was on the motorcycle, I had to avoid losing money. To do so, I had to buy a belt bag, because the cash every night was half my one-month salary.

This time, though, I knew what I was charging, even though it was lower than the minimum wage. He had public holidays, unemployment benefits and real insurance in the event of an accident. Unlike Glovo, he did not spend half a day without doing anything and without charging, which also helped to spend more time faster.

At all times under GPS control, I felt under much greater control. If I diverted a bit with the bike they

called me from Barcelona

However, the most obvious difference was that Mrs. Ganja was more than with Glovo. The basic wage was EUR 5.20 per hour or EUR 832 per month if working full-time (compared to EUR 900 of the minimum wage in Hego Euskal Herria). With each shipment they pay a plus that allowed me to collect more than EUR 6 per hour: A little more than I gained with Glovo and much more than the benefits of many riders, as I've been told. It is true, with more contract and more pay I was forced by a boss who banned me from smoking during working hours, but... Compared to the “freedom” offered by Glovo? I would prefer a contract.

At Telepizza, despite finding ways to smoke during working hours, I felt much more subject to control. For example, if I diverted a little from the road with the bicycle, they called me from Barcelona. Of course being older isn't fun, but much less that it's GPS-controlled at all times.

Overall, the older adults' activity was quite nice. I have read through the Internet many allegations of cruelty and illegal behaviour from the main Telepizza players, and I think they are truthful, but my superiors were trying to make work graceful. The schedule, however, was the worst of the work, as in Glovo. He had days of two or three hours, so to be able to do 22.5 hours a week he had to work almost every night, even on weekends. Before the start of the working day I had to be there to wear the uniform and, in addition, I was coming out too late to account. Also taking into account the time to go back and forth to the restaurant, I had to add one hour each day.

For those who spend eight hours in a workshop, working fifteen minutes without charge can be little. But for those who work in short days, these small periods can accumulate gradually until they reach the eight hours a week that have not been paid, which is 26% of the time worked. When they could, the bosses allowed us to leave a few minutes earlier to take off the uniform, but this was not common: our days were extremely strict to adapt to the clients' schedules.

The more difficult it is to find workers for a company (Telepizza wants people with a driving licence and has to pay more to dismiss employees), the more traditional the way the company exploits them. The owners of the premises try to improve the work environment, but the company pays below the minimum wage. Their uniformity makes the arrival at work earlier and not entirely satisfactory. However, unlike Glovo, we always ended up with the same phrase: “Well, we knew what work this was.” My boss also told me that when I told him I was going to quit the job, he understood the decision and didn't try to convince me to stay. If the owners abuse the workers, at least we are all aware of that.

I liked being off on a bike, but the atmosphere at the restaurant was quite disappointing. Some distributors and cooks have worked there for about nine years, some of whom had nothing to do and were already hours earlier in the same restaurant in full boredom or excessively abusing 50% of their employees’ discount. Other workers were students who were bored with their work or who were exhausted because they had more work than that. The most mysterious, though, were the older ones, especially those who took the job seriously: you couldn't understand what motivated middle-aged professionals to stay in such a place.

In the revolting waters of global capitalism Soon after I started working, I found out about a viral tweet on Twitter. One worker sent a public message to the Telepizza account showing his dissatisfaction with the treatment received by the company. The message was ambiguously written on purpose and Telepizza, believing that the person was a customer, responded quickly by offering help to solve the problem. The worker then made it clear to them that he was complaining that he was not even paid the minimum wage. As expected, the speed with which Telepizza responded ended at that time.

This is the first case in which I have known this event; later, I have seen boycotts, strikes and fights in the courts. Most workers have joined the CGT and UGT trade unions, particularly in Barcelona and Zaragoza, where more than 70% of the workers took part in the strike. After two months, Telepizza had to recognize that he was not paying the minimum wage, so he accepted a partial increase of 50 cents per hour.

This seems, in part, to be a traditional trade union struggle against an exploitative company. With those strikes, they got something. Telepizza does not have an ambiguous legal obligation on Glovo and that is why workers have taken advantage of the strike to collect the minimum wage and what is owed to them since the beginning of 2019 (although I am still waiting for them to appear in my bank account).

In this case, the potential of the traditional working-class struggle can be seen but, in turn, it has highlighted the limitations that this struggle has on the new globalised economy. Telepizza was clearly breaking the law. Subsequently, under pressure, Telepizza will only be able to give the minimum required by law, no more. Both positions have the same reason n.Para to understand the

account of these illegal wages in its entirety, we have to resort to the offices of big companies, in the United States. In this story, it is a simple enterprise, inspired by the easy money of the American dream and by the food of garbage, which wanders through the revolted waters of global capitalism.

Telepizza was founded by a Cuban after learning about the pizzas distribution business in the United States. It brought to the Spanish state that franchising system and that centralized fordist mold of selling fast food. However, he has had very strong rivals in that challenge (Pizza Hut or Domino’s, for example) and has accumulated a very high debt because of them. Following the 2008 crisis, the drop in consumption has forced the company to pay a debt of EUR 35 million per year. At the time, many believed that the company was about to disappear.

As usual, international bankers and venture fund managers perceived a smell of blood. Among them was KKR, a U.S. investment firm known in the 1980s for the aggressive purchase of weak businesses. At first, Telepizza tried to suck, but then it changed the tactic a little bit. Instead of the liquidation of their assets after the purchase of a company, they are now making huge investments in companies that allow them to monopolise an entire industry. The KCR has achieved great success with this strategy: its assets amount to 545 billion dollars, one third of the Spanish State’s GDP. They have opened offices around the world and have about one million workers, whose influence and resources resemble many states.

When I started working for Telepizza, in the summer of 2019, there was a big change in the company. It became part of a new parent company, Telepizza Group, of which the KCR was made with 80% in exchange for around EUR 400 million. In addition, at the same time, Telepizza Group purchased Pizza Hut, which has become the largest manager of many brands in the world in the pizzas distribution business and the largest market owner in the Spanish state.

Now, on this larger scale, the centralized production of pasta, cheeses and other ingredients that Telepizza has always had will be even more profitable. It will pay much less for the basic ingredients, as it will buy them in larger quantities than ever before. By reducing two management structures you will be able to achieve the same performance with fewer employees. This has been the case, as the latest reports show that after the purchase of Pizza Hut, its operating margin has increased from 10.7% to 12%.

Likewise, as Telepizza expands, workers will be less likely to find another job in the same sector, and Telepizza will have more money to pay the costs of litigation against trade unionists. As the presence increases, as more is invested in the urban landscape and in marketing and in its app, the consumer will have fewer opportunities and more difficulties to know that there is more. In a word, the stronger Telepizza is, the weaker the others will be. Or, in financial terms, poorer.

KCR’s investment with Telepizza has become a common practice among the giant investment groups: providing companies with the ability to monopolise a certain area of money, giving them a decisive advantage against their competitors. However, the firms that make this type of investment in Spain seek to obtain large profits in exchange for such an investment. The KCR has acted in the short term by buying and destroying companies, trying to gain quick profits. Now, however, they have learned that, to the extent that the acquired companies can create monopolies, the productive profit can be maintained at little cost.

Why does Telepizza not pay the minimum wage?

This is not an infamy, but the consequence of a large international system based on high-risk monopolistic investments. Its goal is for the international investment firm and the richest people in the world to become even richer by paying as little as possible to all employees. Telepizza, insofar as it is under your dependency, can do nothing else. It is not possible to maintain responsible conduct in the businesses of this scale, they have no stimulus or pressure to promote them.

Telepizza and Glovo are parts of the same system, but they operate with different business models. Telepizza can be the most dangerous of both. Why? Only because writing about it is not so exciting, but because it has consequences for our lives and our economy.

Telepizza doesn't pay the minimum wage because it's part of a global financial system that has generated historic levels of inequality. The system adopts companies in vulnerable situations and makes them efficient to maximize profits and crush souls. Glovo started with that model, Telepizza suffered a kind of half-life crisis, but now they're the same beast. A local pizzeria may have a slower or more expensive service than Telepizza, but they have a much greater responsibility both with their workers and with society. It's useless to boycott Telepizza for wages to rise. There we should stop buying and definitely abandon this kind of business.

Reporting translated into Basque by Diego Pallés Lapuente

Betsaide enpresan gertatu da, 08:00ak aldera. Urtea hasi denetik gutxienez bederatzi behargin hil dira.

2024ko laneko ezbeharren txostena aurkeztu dute LAB • ESK • STEILAS • EHNE-etxalde eta HIRU sindikatuek aurtengo otsailean. Emaitza larriak bildu dituzte: geroz eta behargin gehiago hiltzen dira haien lanpostuetan.

Jakina da lan ikuskariak falta ditugula geurean. Hala ere, azken egunotan datu argigarriak ematea lortu dute: lan ikuskaritzaren arabera, EAEko enpresen %64ak ez du ordutegien kontrolean legedia betetzen. Era berean, lehendakariordeak gaitzetsi du, absentismoaren eta oinarrizko... [+]

-(1).jpg)