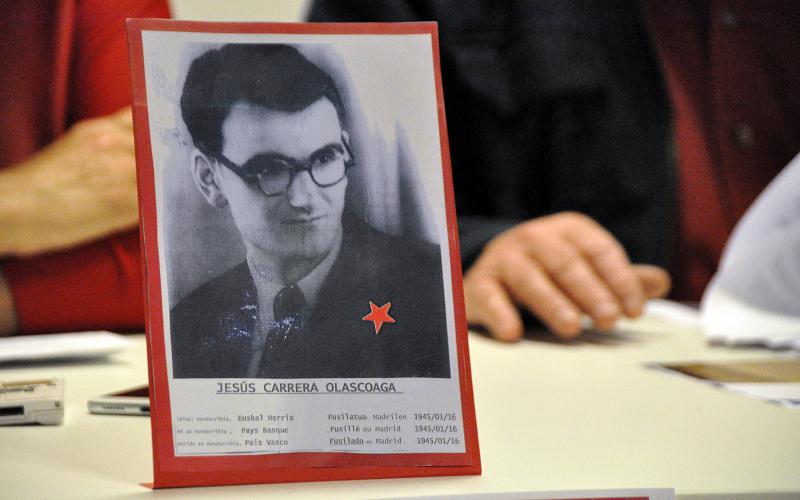

Portrait of a shattered coastal town with feathers of a special tourist

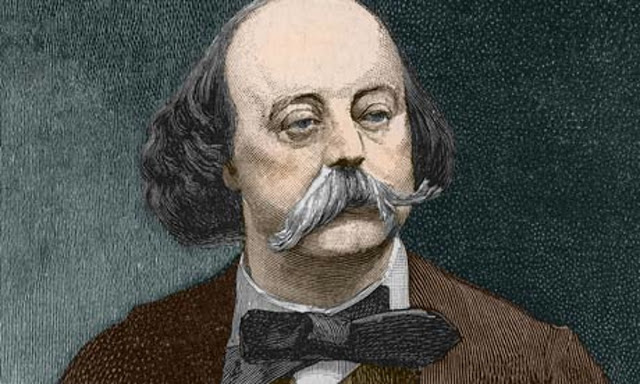

- Gustave Flaubert’s journey in Euskal Herria as a young man is not well known to the Basque public. Before the writer wrote his great works, he met several towns in the area and several of his impressions are gathered in a book published after his death. It's worth going back to them. In this article we recovered what he said about Hondarribia.

In 1840, when he was 19 years old, after a quite rough career as a student, and taking advantage of the money provided by his parents, Gustave Flaubert travelled through the Pyrenees and Corsica. He was someone who since he was young had fallen into alphabet addiction, a writer very early in his century – he was 13 years old when he published his first text in the manuscript magazine Art et progrès, created by him and his colleague Ernest Chevalier. Therefore, Flaubert, who appears in the lines he wrote about this journey, is not yet the one who with great novels such as Madame Bovary or L’Éducation would become a literary rockstar of the 19th century. But yet, it's Flaubert Flaubert. One of the great writers in French literature, entirely canonical, is a source of inspiration for many writers today. Perfectionist in the style, lived the account of the century in which he lived – if we breathe a gram of that passion for using “le mot juste” the journalists that we write more and more slowly, ah, then – and that is why the little attention he has received about Euskal Herria is striking.

Take the case of Hondarribia, for example. If you go into the municipal website, it is said that two important 19th-century French writers wrote about the people – Victor Hugo and Stendhal – but Flaubert does not appear at all. It is as if in the 1973 Iggy Pope, David Bowie and Lou Reed played in the Benta, and now we do not mention one of the three: a vacuum that draws attention, probably attributable to the lack of knowledge of Flaubert's text, which was also published in the book Voyage dans les Pyrénézulées y Corse.

.jpg)

We're going to take the sleeves to the elbow and work a little bit with those beautiful pages. After explaining that the Bidasoa has taken him to Hondarribia and despising the Island of Faisanes – which did not deserve a mention – Flaubert is at the front door of the old town. He walked in and pulled out a barefoot, "barefoot, in red suits, leaning on his shoulders. He did not turn his head and followed his path. Hondarribia is about to fall. You don't hear any noise in the streets, the grass is pushed against the scorched walls, there are no windows in the houses. The main street is straight and abrupt, surrounded by black houses, with corrupted balconies, in which large red rags dry in the sun; we have come up slowly, looking everywhere and even more looking.”

Well, if you're a little Hondarribitan chauvinist, the truth is that it doesn't start very well. But, hey, you heard the last shots of the First Carlist War when the writer, born in Rouen, went over here, you couldn't ask the people to be so nice and brilliant with the blocks of strips and freshly finished puppies. In addition, the thing begins to improve, because it seems that Flaubert had a trip in the streets of the town: “As I went through Hondarribia, I completely opened up my impressions, I enjoyed the excitement, a sensuality that I wanted to devour everything; I immersed myself with all my strength in my imagination, I completed images and illusions and I dedicated myself with all my pleasure to lose and immerse myself.”

Singing a woman interrupts this situation of satisfaction. The slow and sad rhythm of a “Spanish song” draws the writer’s attention: “She was probably an elderly woman, her voice trembled and seemed to regret something that had disappeared. I couldn't see anything, the street was deserted, the sky was blue and bright on our heads, we all shut up. What did that Spanish song, sung with an old voice mean? Was it the mourning of the dead? Back to the years of youth? The memory of a good time that no longer exists? A song of war sung about these rubble? Or the love song whispered by the old unknown?” In this doubt, another voice, younger, begins with a more joyful song that Flaubert describes as a bolero, but soon ends the song that the writer equips with the melody of the grasslands.

So keep on foot, avoiding the wells presented here and there in the middle of the street. “We don’t know where we are going, the people also have the impression of drifting and thinking about painful things.” The phrase is understood a little later, when he meets a fisherman and shows him the post that was used to shoot garlands during the war. “As the Carlists have resisted, they have fallen one by one, as the Middle Ages fell from stone to stone, but they have had to tear them off and many nails have been torn apart; every house, every door, every beam is vaulted with bullets, the church has raised cannons, the enemy howits have reached Behobia and killed men.” Suddenly, it seems that the bohemian, the stylist, the carefree traveler cannot do more abstraction than it surrounds him.

He spells out the things he has said before: the scorched walls, the black houses, the girl with bare feet who goes past without looking, the paisano stalking the visitors who have seen well, the sad song of an old woman. They are images of the postwar, the Hondarribia of 1840, the Syria of today, what matters, the corpses are still warm. Later, he will head to the Madalena district, where the children will surround him in the Samalda area, hoping to receive some alms. Flaubert: a rich man in the last village of Gipuzkoa torn apart by death and misery. Is there no mention of what this illustrious visitor wrote because he gave that sad image? The writer, however, had one clue left: “I left Hondarribia, with the pain of something loved.”

11 adin txikikori sexu erasoak egiteagatik 85 urteko kartzela zigorra galdegin du Gipuzkoako fiskaltzak. Astelehenean hasi da epaiketa eta gutxienez martxoaren 21era arte luzatuko da.

EH Bilduk sustatuta, Hondarribiako udalak euskara sustatzeko diru-laguntzetan aldaketak egin eta laguntza-lerro berri bat sortu du. Horri esker, erabat doakoak izango dira euskalduntze ikastaroak, besteak beste.

AMAK

Company: Txalo teatroa.

Created by:Elena Díaz.

Address: Begoña Bilbao.

Actors: Finally, Ibon Gaztañazpi will account for the details of Intza Alkain, Tania Fornieles, Oihana Maritorena and IRAITZ Lizarraga.

When: 10 January.

Where: Auditorio Itsas Etxea... [+]

«Gatazkaren konponbidean baliagarria izango delakoan» EH Bilduko Lantalde Feministak egindako hausnarketa plazaratu du Arma Plazan. Igor Enparan alkateari «Jaizkibel konpainiak bakarrik betetzen duen legea betearazten hasteko, eta Alarde bakarra, guztiona eta... [+]