When left and right are the same

If science contributes something, that's understanding. Understanding in communication. Need to create a common place to name and say things. In the case of plants and other living beings, a two-word system was chosen, and above the local denominations, whatever language it has, it will understand who is mentioned with those words. For example, the common pumpkin is designated with the maximum cucurbita. The first is gender, and the second is what kind of this genus it is. Within the species there can also be subspecies, varieties, crops, hybrids, etc., which complements the double-name system behind. This is intended to seek the strictest possible accuracy of the designation. For example, if the pumpkin is maximum Cucurbita, the pumpkin of Potimarro Cucurbita maxima Duchesne ssp. maximum cv. The maxim is ‘Red Kuri’. And it's true that you risk getting lost in the pursuit of accuracy, or going crazy about names. As research deepens, plant names change. What we once put into one genre we now see in another. New plants also emerge from some plants, created by natural hybridization or by ourselves, such as flower orchards and vegetables. Those who make decisions in that name mess don't have much to do!

They walk in a similar way to make descriptions of the plants, so that everyone understands us, agreeing and pacing the bases. When it comes to giving and receiving explanations about what a plant is like, we also have to understand each other.

Descriptions and explanations refer above all to what we see, the favorite is the favorite. It is rare to use other senses – smell, ear...–. So what do we see?

With the climbers there's a nice story. Climbing plants have varied tricks for climbing. To grab and stretch the bottom, some give spirals (e.g., peas, Pisum sativum), other roots (ivy, Hedera helix), and suction cups (Japanese hihedrias, Parthenocyssus tricuspidata). There are some that have sarsions at the end of the plant, and it's this climbing plant that will continue going round to what's going to mature, without special organs. When explaining the growth of sardine, it has been agreed among the botanists that if fasting takes the clockwise course, it must be said that it grows to the right; and if it grows upside down, it is to the left. If you look at the plant itself, where it is said to grow to the right, it rises to the left forward, wherever it looks. For example, the plant we call atxaparra, Lonicera spp. that's right. In the 20th century, hops (Humulus lupulus) were built in the villages of Gipuzkoa called the left madreselva. They grow to the right for botanists, they're dextrórsum. In the same way, Convolvulus arvensis and Calystegia sepium, which grow to the left for botanists, are in Euskera a very beautiful left, and we see that both grow to the right.

Botanists have defined it, but the left and the right for the Euskaldunes that we live in Euskera are the same. Apparently.

Udaberrian orain dela egun gutxi sartu gara eta intxaurrondoa dut maisu. Lasai sentitzen dut, konfiantzaz, bere prozesuan, ziklo berria hasten. Plan eta ohitura berriak hartu ditut apirilean, sasoitu naiz, bizitzan proiektu berriei heltzeko konfiantzaz, indarrez, sormen eta... [+]

Ohe beroan edo hotzean egiten da hobeto lo? Nik zalantzarik ez daukat: hotzean. Landare jaioberriek bero punttu bat nahiago dute, ordea. Udaberriko ekinozio garai hau aproposa da udako eta udazkeneko mokadu goxoak emango dizkiguten landareen haziak ereiteko.

Duela lau urte abiatu zuten Azpeitian Enkarguk proiektua, Udalaren, Urkome Landa Garapen Elkartearen eta Azpeitiako eta Gipuzkoako merkatari txikien elkarteen artean. “Orain proiektua bigarren fasera eraman dugu, eta Azkoitian sortu dugu antzeko egitasmoa, bere izenarekin:... [+]

Itsasoan badira landareen itxura izan arren animalia harrapari diren izaki eder batzuk: anemonak. Kantauri itsasoan hainbat anemona espezie ditugun arren, bada bat, guztien artean bereziki erraz atzemateko aukera eskaintzen diguna: itsas-tomatea.

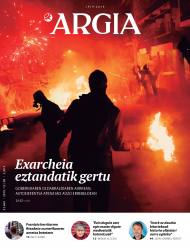

Aurten "Israel Premier Tech" txirrindularitza talde israeldarra ez da Lizarraldeko Miguel Indurain Sari Nagusia lasterketara etorriko. Berri ona da hori Palestinaren askapenaren alde gaudenontzat eta munstro sionistarekin harreman oro etetea nahi dugunontzat, izan... [+]

Sare sozialen kontra hitz egitea ondo dago, beno, nire inguruan ondo ikusia bezala dago sare sozialek dakartzaten kalteez eta txarkeriez aritzea; progre gelditzen da bat horrela jardunda, baina gaur alde hitz egin nahi dut. Ez ni optimista digitala nauzuelako, baizik eta sare... [+]

Bada Borda bat ilargian. Bai, bai, Borda izeneko krater bat badu ilargiak; talka krater edo astroblema bat da, ilargiaren ageriko aldean dago eta bere koordenadak 25º12’S 46º31’E dira; inguruan 11 krater satelite ditu. Akizen jaiotako Jean Charles Borda de... [+]

Donostiako Amara auzoko Izko ileapaindegi ekologikoak 40 urte bete berri ditu. Familia-enpresa txikia da, eta hasieratik izan zuten sortzaileek ile-apainketan erabiltzen ziren produktuekiko kezka. “Erabiltzaileen azalarentzat oso bortzitzak dira produktu gehienak, baina... [+]