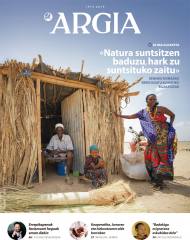

The life of North Hor in Kenya becomes a resistance action for farmers

- The climate emergency has forced nomadic farmers in Kenya to change their customs. In the rain stations, the drops do not fall and, as a result, the water wells have dried up. These communities could become climate refugees in the not so distant future.

In silence and following a certain rite, the men of the village of El Boru Magadho have cut their heads to the goat. It is a common action every time the new station arrives. People wait for the goat to bleed to death and take out the intestine. It's not a Macabre rite, it's a century-old habit. The intestines serve as a climate prediction for members of the Gabra community in Kenya. The elders of the village, the Junta de Sabios, read the intestines and “correct” what the next station will look like.

After the death of the goat, five elderly have been cited in the vicinity of the intestine. It is about analyzing the color of the digestive system and the main lines to predict how the next season will be. The Board of Wise Men does not doubt that. “The rain is approaching and the next few weeks will be good,” said one of the five. The others were intimidated. Among the villagers, who have been spectators of the rite, there is joy.

.jpg)

However, the farmer Guyo Gonjoba is not very convinced. “My father is one of the five elders, but in recent years he doesn’t know. However, not a drop falls. Three months ago he said the same thing and nothing.”

For years the nomadic farmers of El Boru Magadho have been suffering the consequences of the drought but 1993 was a turning point

For years, nomadic farmers in El Boru Magadho have been suffering the consequences of the drought. Guyo, 45, remembers when he experienced the change: “The year 1993 was a turning point. The rainy seasons failed and I went to look for answers to my grandmother.” But the matriarch of the house said: “The Arbayas (the gods) have become angry.”

Since then, the situation has gone from bad to worse. “The rain does not respect the usual stations and we are seeing extraordinary wind streaks,” Guyo explained. The Gabra community lives around the Chalbi desert between Kenya and Ethiopia. North Dotes is the largest municipality in the area. “We are farmers and we are used to living in extreme conditions,” Guyo said. But in recent decades, the balance between nature, man and animals has been broken.

Older people join Christian and animist customs to respond to the lack of rainfall. However, young people know that the climate emergency has been caused by

human abuse.

Climate emergency? The farmer has no doubt: “If you destroy nature, he will destroy you. Amalurra doesn’t forget it.” In this forgotten corner of Kenya, there is a generational shock. Older people join Christian and animist customs to respond to the lack of rainfall. However, young people know that the climate crisis has been caused by human abuse and that the transformation has scientific roots.

Most farmers in North Hori live in small villages, a few kilometres from each other. Families build structures called manyattas, circular houses of logs and fabrics. In the centre of the desert there are oasis of springs and palm trees, but farmers prefer to live far from the lagoons. The malaria rate is very high, and mosquitos like oasis.

.jpg)

In the dry season, men bring animals to fresh foras or grasslands. “The fora of our community is 35 kilometers from here. We need several days walking to reach camels and goats,” explains Guyo. Animals and men pass the entire dry season out of the village. Women, for their part, assume the full responsibility of the community.

Gubo Ukuru, the mother of seven children, heads the women ' s assembly of the village of Goricha, involving 35 women. “It’s my responsibility to care for the whole family when your husband and your older son are out.” Ukuru, 52, seems more veteran: “Life has not been easy, always focused on the well-being of the family and the community.” Ukuru reminds us of the time when people were moving according to the station. They were nomadic farmers and it was women's responsibility to build manyattas. Ukuru married a neighbor named Godana at the age of 18 and became a member of the village of Goricha.

.jpg)

In any case, there has been no relocation of the small town in the last five years. The Gabra community is becoming a sedentary people. Ukuru has never wondered what his life would be like if he was born somewhere else. He doesn't have time to think about it. The woman has two children, who are infected with brucellosis, according to the same source. Brucellosis is a common infection among farmers. From animals it is transmitted to humans through milk. Families do not let the milk of goats and camels boil, which causes contagion.

“The milk of the camels is not as good as before. Animals don’t eat enough,” Ukuru said. Guyo is of the same opinion: “Camels can spend 20 days without drinking water, but without eating they can’t spend much time. The lack of rainfall has brought poverty to the farming communities. In dry areas, poverty has spread. As for green pastures, there have been conflicts”. Thus, the farmer fears

that drought may lead to a war between the communities, which have not yet recovered. “Gabr has never had problems with neighbors. The pastures of our family are located next to Lake Turkana and we share them with other groups. In this area there is no private property, the lands are state,” Guyo explained. But lately there's not enough field to fill the vientres of all animals.

.jpg)

And not only that. Many of the wells where water is extracted have dried up due to the evacuation of aquifers. Many other wells are contaminated by corrosion of minerals: “Do you see that big hole?”, says Guyo, “it’s a big pond, but last January 175 camels died for drinking water from the area.”

Because of the problems arising from climate change, Guyo assumes the responsibility of the community: “Two years ago my father called me on the phone. I was very worried. He told me that family survival was in danger and I didn't think twice. I fired from Nairobi and returned to El Boru Magadá,” the farmer remembers. In fact, Guyo was for many years a Protestant priest: “When I was young I wanted to know the world and I went to the capital. But I am the older son and I have a great attachment to the family.” So, Guyo marries a girl from the village and lives with her wife and her two daughters next to her parents' manyatta.

.jpg)

The farmer has introduced new technologies in the daily life of the community: Guyo joined the pioneering project launched by the Polytechnic University of Turin in Italy. The initiative is called TRIM, and it's a mobile app. TRIM collects meteorological data, animal diseases, flora and wind direction and provides farmers with a database based on the GPS system. The objective is to signal through the mobile the location of fresh water wells and grasslands.

"Mobile app doesn't work miracles but it makes it easier for us to do the job."

Guyo becomes a data collector: “The new application does not work miracles, but it helps us understand certain patterns. We identify what climate trends are and try to give them a faster response. We know it’s a temporary patch, but it makes our work easier.”

.jpg)

Continuing to live in North Hor has become a resistance action for livestock communities, and that struggle is not only linked to the climate emergency. From Marsabit it takes five hours to get by car to El Boru Magadel.Hay than to cross the Chalbi desert and there are no roads. The isolation of the area has helped to maintain customs, but the Kenyan authorities have begun this year to pave the way. "What's going to happen when village elders die?" ", Guyo asked. It seems difficult for the new generations to maintain the livestock tradition. “Many young people have gone to college and others have escaped to the tourist areas of the coast. My brother, for example, works in a big hotel in Mombasa,” Guyo said.

The authorities in Kenya have begun to tarnish the path. Urbanize or abandon. These farmers can become climate refugees.

Urbanize or abandon. The farmer sees no alternative. In fact, it's clear that climate change doesn't turn back. “Maybe we have to cross the borders of Kenya and hit the gates of another country. I want to remain a farmer, but for that we have to go further north of Ecuador.” Guyo does not know what climate refugees are, but it can soon become one of them.

There was no one or all. That we all suffer at least if the necessary changes are not made so that no one suffers the climate emergency. You – reader – I – Jenofá-, they – poor – and they – rich. The fires in Los Angeles did not give me satisfaction, but a sense of... [+]

The understanding and interpretation of the mathematical language is what is important in the learning process, at least it is what we say to our students. The language of mathematics is universal, and in general, the margin of error for interpretation tends to be small. We... [+]

Recently, when asked what the climate emergency consisted of, a scientist gave the excellent answer: “Look, the climate emergency is this, you increasingly see on your mobile more videos related to extreme weather events, and when you realize, it’s you who are recording one... [+]

In recent weeks it has not been possible for those of us who work in architecture that the climate phenomenon of Valencia has not been translated into our work discourse. Because we need to think about and design the path of water in decks, sewers, plazas and building parks. We... [+]

-(1).jpg)