Allende's spirit is embodied by students in Chile

- In Chile, immersed in the neoliberal economy, there is a political subject referent to other countries of the world: students. 2019 has started with incidents, and there are those who announce a hot course, as the government has also come to face serious difficulties.

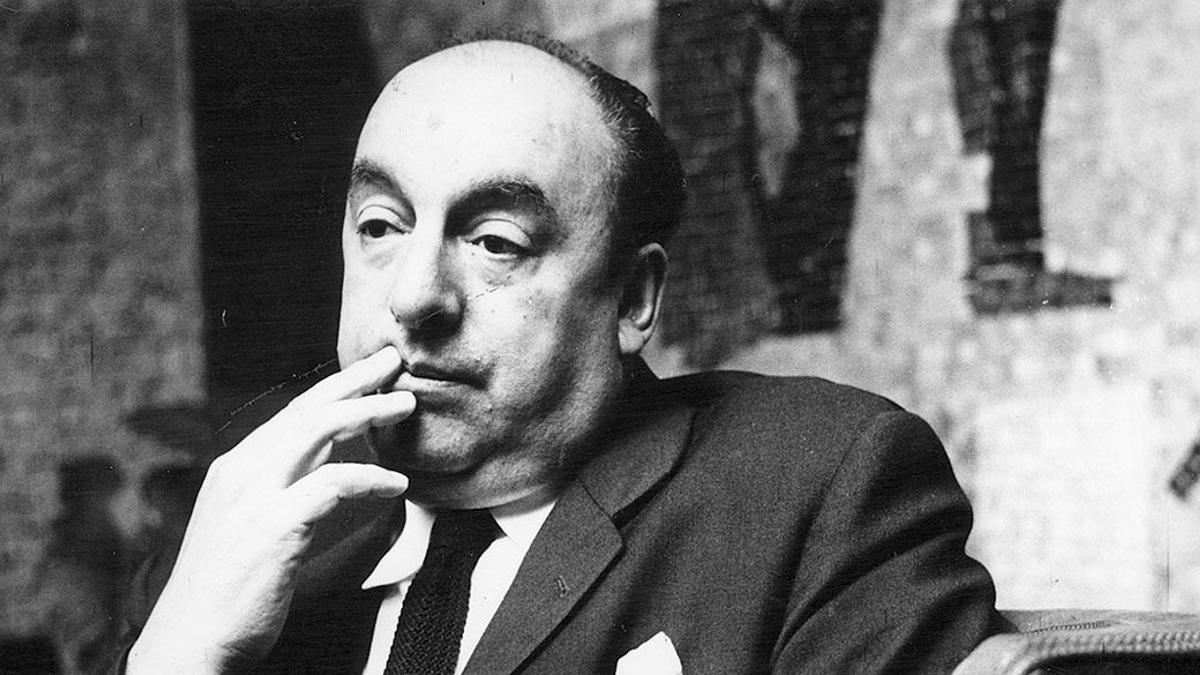

The figure of Salvador Allende, with a rifle in his hand, has been stuck in the imagination of many citizens. However, it is not so well known that in his youth he was an important representative of the student movement.

In 1921, when he finished high school, he met anarchist zapatero Juan Demarchi in the city of Valparaiso. Man taught him to play chess and he himself recognized that it had been one of his main influences, as during time they were dedicated to playing and speaking in chess. Allende first received Marxist texts from Demarchi, which helped him strengthen the social conscience he had already awakened.

While in jail, his father died and swore that he would take the fight for his ideas to the extreme.

In 1926 he began studying Medicine at the University of Chile and for years he was an active agent of the student movement. He founded the Avance Group with several of his colleagues and became vice-president of the Federation of Students of Chile, from where they fought against the dictatorship of Carlos Ibáñez. In 1932 it barely lasted three months when the people active in the Socialist Republic of Chile suffered harsh repression during their subsequent government, and Allende was arrested that year. While in jail, his father died and swore that he would take the fight for his ideas to the extreme.

Chile, since the 1973 coup d ' état, has been immersed in neoliberal policies and has for years been the principal ally of the United States in South America. Since the end of Augusto Pinochet's dictatorship in 1990, leftist and right-wing governments have shared power, but investigator Felipe Portales denounces that Chile has never made a transition to a real democracy. An example of this is that some dictator’s laws are currently in force. The liberalized activity, designed by the Chicago Boys in Economics, is a leader in the country. To this neoliberal policy, students have been opposed as active subjects and for years have taught constant teeth to the political class.

“The homeland will not wait!”

In 1987, the rector of the University of Chile, Roberto Soto, took the necessary steps for the democratic election of high university officials. Pinochet saw this with bad eyes and impeached Soto. He replaced José Luis Federici, a civilian who held important positions in state-owned enterprises, as rector. The students responded immediately, understanding that the new election was contrary to the democratization of the university. A few days after the election of Federici, teachers and students denied him legitimacy and called for the strike.

Despite the cruelty of the dictator, the streets of the major cities of Chile were filled with students during those days and received the help of many citizens. On 24 September, an event took place which completely conditioned the future of the protests. A demonstration that started at the university as she approached the Municipal Theater was shot in the head by a carabinera (Chilean military police) and was arrested on charges of "assaulting a police officer." However, a means of allegal communication, called Teleanalysis, had recorded the event and the recordings show that the protester did not carry out any type of attack, but fired for no reason. Turning upside down the version of the official media, the role they played for the dictatorship became apparent, and it conditioned the days that followed.

This led to the polarization of the movement and some students started a hunger strike. The demonstrations multiplied in the Chilean capital, which led to clashes between the strikers and the reactionary groups in favor of the dictatorship.

The end of these protests took place at the Law School of Santiago de Compostela. In the streets of the capital, crowded with students, Federici changed the Dean of the Faculty of Law and established a lawyer in favor of Pinochet. This provoked the indignation of the students, who entered the office of the new dean and destroyed it. Pinochet himself approached the university, and in the face of the gravity of the situation, he asked Federici to resign on October 29.

“We will take this fight to the end. Here there is no draw, we will win everything or we will lose everything”

As a result of these strikes, many citizens from different sectors fought together against the dictatorship: workers, students, teachers and civilians. The majority of the population managed to get their views on the system at the time on the table. From that time it is the general strike they carried out under the slogan “Bread, work, justice and freedom!”. The words of the president of the Chilean Federation of Students of the time, Germán Quintana, to the Teleanalysis medium, highlight the extent of the tension these days: “We will take this fight to the end. Here there is no draw, we will win everything or we will lose everything.” Pinochet placed the philosopher Juan de Dios Vial in the position of Federici, which the opposition considered a great triumph. In addition, the shortcomings of the reactionary and military groups favorable to Pinochet were evident.

The Penguin Revolution

The main conflict between the Chilean student movement and the state in recent decades has been that of the Penguin Revolution or the Penguin Movement in 2006. This movement, which refers to the similarity of the students' uniforms with the bird, is for many the most massive mobilization of the 20th century students in the world. Not only because of the number of students who were able to move, but also because of the size of the offensive they made to the state. This phenomenon completely determined the politics and daily life of Chile and was internationally renowned.

At first this movement called for the improvement of secondary education infrastructures. However, the mobilizations also had another background: to put the debate at the centre of the political agenda on the quality of education at all levels and the role of the State in education. And they did.

This fighting period lasted from April to October 2006. During the disturbances, in April, a group of students mobilized to demand access to university and free school transportation, and 47 students were arrested. Even though these mobilizations were quite marginal, they were the background to what would come next. In May, the students began to organize themselves, and on 26 May, unexpectedly, thousands of students went on strike and out on the street. Last day 30, the National Student Strike was convened, which mobilized more than 700,000 students in a country of 19 million inhabitants. The facts originated from the government's alarm, and the following day the president, Michelle Bachelet, with the intention of calming the situation, showed in a press conference in favor of the students: “Students have made their requests known and I find them fair and legitimate, because they want to improve education.” In the following days more strikes were called, and before the success of the previous call, he tried to deactivate them: “The calls for strike that are currently being called are not necessary,” he said.

However, the movement quickly acquired a larger dimension and called for the repeal of the LOCE education law. LOCE was Pinochet's last major bill, as it was passed on the last day of the dictatorship. As in many other areas, the dictator liberalised education and made it available to the private sector. In these 2006 protests, students demanded that education be in the hands of the state and public investment to solve the problems of public education.

The students demanded that education be in the hands of the State and public investment to solve the problems of public education.

Strikes and mobilisations continued in the coming weeks, but the movement began to erode, as the contradictions between radical and moderate sectors led to an internal breakdown. From there, part of the students continued to mobilize, but the movement did not have more strength or higher level of initial unit. However, the movement has a great influence, as two years later the General Education Act (LGE) was passed, following a cross-cutting agreement between the political forces and Congress.

In a study carried out in 2007 by a Research Institute on Governance in Paris, one can read the impressions of Natalia Núñez, who, 17 years old, was immersed in the Penguin Movement at that time, according to him, what are the strengths and weaknesses of the movement.

“The movement has been the best phenomenon in this country. It was achieved above all by unity”, notes Núñez in the study, emphasizing the strength of society to fight in specific situations. It says that there was great pressure on the Government, and that that, at the same time, made the demands really possible. However, he considered that the petitions were excessive, which took away seriousness, giving politicians the opportunity to “infantilize and discredit students”. On the other hand, he said that excessive demands "complicated the internal environment of movement" and he assured that it was one of the causes of internal fractures.

The 2006 Penguin Movement was a huge struggle among Chilean students and was the first political experience of many young people.

'Aula Segura' Law against Students

In 2018, the government, chaired by the independent Sebastián Piñera, adopted a new measure against students fighting through a direct route. The law is called Aula Segura and offers school principals facilities to expel students immersed in “cases of violence”. This fact has revived the student movement that was off after the 2011 marches and strikes.

The Aula Segura Law aims to end the "cases of violence" that have occurred in recent years in various schools in Chile and has been criticized by various agents of the student movement and the educational community. Two experts from the Observatory of Education 2020 and Educational Policies of Chile have denounced that the law was made “with little patience and without much thought”, in an attempt to seek “a quick exit” to some incidents that occurred with groups of students.

The students immediately identified this measure as a direct aggression and mobilizations have been launched. In this situation, high school and university students have started in 2019 with mobilizations and strikes, and there have been clashes with the military police in the demonstrations. On April 25, 20,000 students took to the streets in marches organized by the Chilean Federation of Students and 35 students were arrested in clashes against carabinierías. Six underage students were arrested in their homes, accused of using "incentive bombs" against teachers, according to the same sources.

The spokeswoman for the Chilean Federation of Students, Belén Larrondo, has denounced that the Government does not respond to the demands of the student movement: "The Government has not shown its willingness to improve ill-implemented measures, such as gratuitousness, and is taking continuous steps to address the shortcomings. However, these measures do not have the objective of radically changing Chilean education”.

Protests against the Aula Segura law have not been strong enough to mobilize the student mass mobilized by the Penguin Revolution, but have served to demonstrate that the student movement in Chile remains firm and that it can be a real challenge for the state. After all, the student movement in Chile has internalized Allende’s philosophy: never give up, although in some times less people can move around.

One of the main conflicts of Chilean President Gabriel Boric since the beginning of his mandate has been the conflict in the territory of Araucania in the south. In recent years, the struggle between the Mapuches and the Chilean state, among others, for land ownership has... [+]