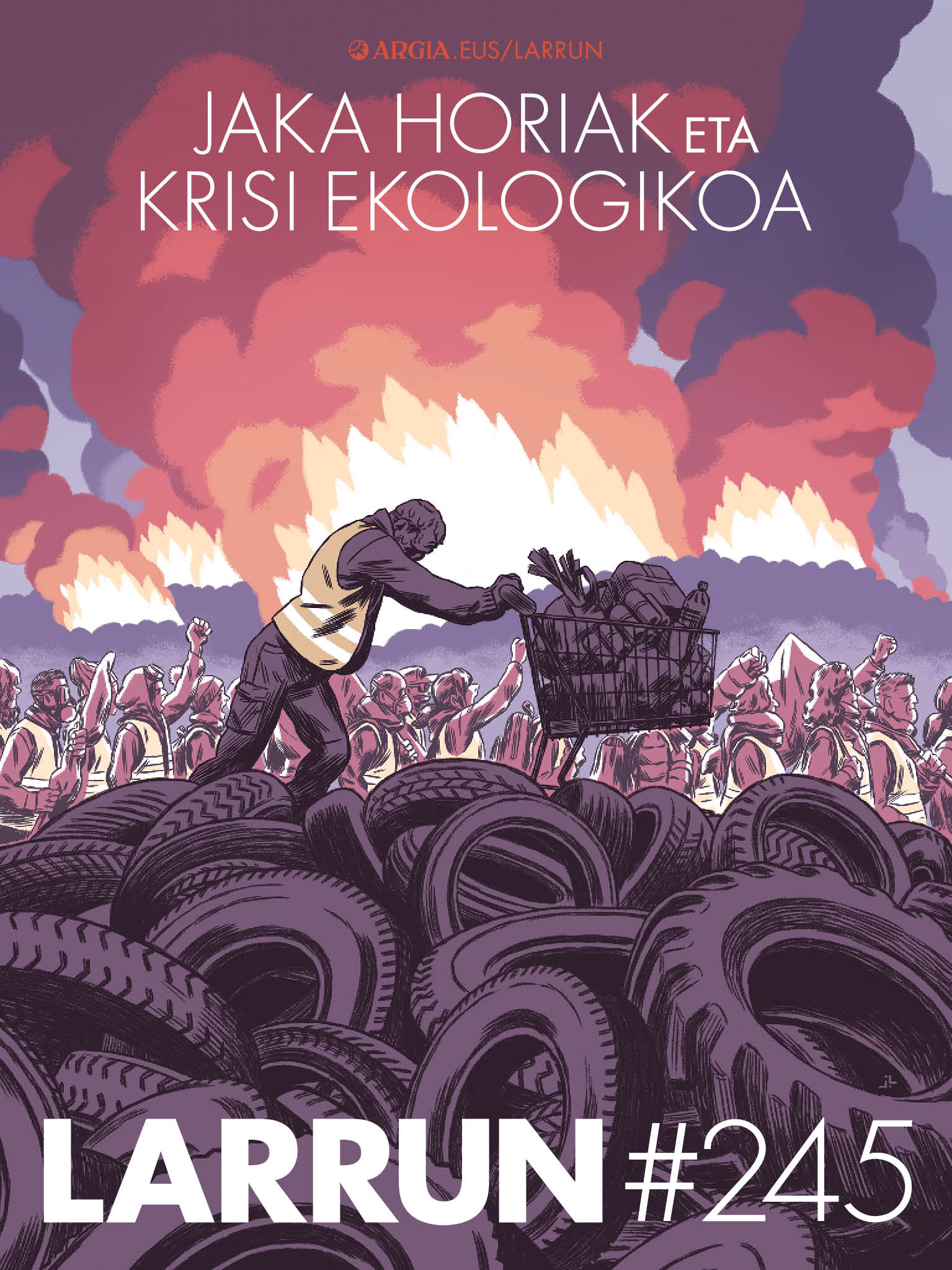

Yellow Jackets and Ecological Crisis of France: End of month versus end of the world

- The movement of Jaka Hori (Gilets Jaunes, in French) started in October 2018 and a year later is still alive. Is it too early to take stock of what it has brought and what it has failed? From the other side of the sea, from England, Simon Fairlie has tried and published the End of the Month, End of the World that we have translated into Basque for LARRUN, after spending several documented weeks on the subject and getting to know Jaka Horiak from France. Yellow Jacket explained by an English to the British… can be an interesting perspective considering that the Light is mainly used by readers with Spanish ID. He has already written in French: May 1968 in the Countryside (May 1968 in the countryside). The farmer and journalist Fairlie has just brought him to the pages of ARGIA Keys (Is it sustainable and ethical to eat meat?) on account of the vegan/non-begano debate: Meat has just published arguing that small livestock farming is beneficial to the environment: To Benign Extravagance (Okela, gutizia, no harm). After working with the finished university in agriculture, grazing, quarrying and other trades, he was director of the mythical magazine The Ecologist between 1990 and 1994. Since she left, she has been working on a collective agroecological farm in the region of Dorset: cattle breeding and pigs, she provides harvest courses and sells scythes, while making communications and movements in favour of the environment and agriculture. The Land Magazine is a small but referential magazine that promotes the association Chapter 7, which wants to flee from cities to the countryside and advises those with less resources.

With them I found myself for the first time in a roundabout of the variant of the small industrial village of Bedarieux, in the rural area of the Languedoc region. He had been in France for a couple of weeks, had read a lot about them, had crossed the car window with his paper sheets, had seen his hi-vis vests [high visibility, reflective visible from afar] in the car desks, but he had never been with me. In that place there were a lot of banners and posters, in addition to the French Tricolore flag; the Acte XV. the act], number 15 of the mobilization.

I put the car on and I walked up to the table. About twenty of them were drinking wine, grilled and in a good mood, sitting around a long table on a donkey. I asked them what they protested: their main complaint was the increase in life, how hard it was for them to reach the end of the month, at the end of the month. “On crève de faim” (We are starving to death) said a man combed backwards by the ralo gominoso hair, although the longanizations of the grill and wine of 1.50 euros gave another aspect. Another man, with charreteras and mustache, realized that this exaggeration did not help much and explained that if you earned the minimum wage, less than 1,200 euros, and it took 400 to rent housing… that didn’t seem to pay for the things that today’s life demands. While politicians, corporations and shareholders take the profits into their pockets, President Emmanuel Macron further reduces taxes on elite people.

The concern about the increased lifestyle makes Jaka Among them there is a consensus. But as he continued to talk to two men, the ideological differences between them became evident, which became more evident in the issue of renewable energies. The Gominatario said that if solar panels were used for everything, “it would be necessary for it all the surface of France and we would not have land to produce food.” The mustache did not agree, in his country they have solar panels, which is not widespread in France, where nuclear power is the king. It seemed to me that the gominoso was probably from the right wing of Marine Le Pen, the Rassemblem National, while the vibratory was able to vote for Jeann-Luc Melenchon,[1] equivalent to Jeremy Corbyn in France.

I found that same gap between the different groups and within each group. In the town of Decazeville, in the old rusty city of the Aveyron region, Jaka Hori, I asked a group if they were from the left or the right. “We have no political tendency,” they replied, but then two of them started to talk badly about immigrants, about how they destroyed the homes they offered them for free: “If you like the English so much, why don’t you take our ones?”

After touring twenty-two kilometers on the road, in the next village, Capdenac, I asked the same question to another group and received a different answer: “Here we are all on the left,” a woman told me. “This afternoon we will go to Figeacera for a climate mobilization.” He handed me a hand sheet from the leftist union CGT (Confederation General du Travail).

The exception is that the political choice is so transparent. Its whole movement is difficult to classify in the traditional left and right axes. Its changing character and perseverance beyond what was expected have generated a great national debate and there the lessons are useful for Britain.

.jpg)

Color has become an icon

The movement started from a national day of action against the new petrol and diesel taxes imposed by the Paris Government as part of the ‘green transition’ strategy against climate change. The truck driver Eric Drouet, who had launched the call, came up with asking people to show their love for the yellow jacket that had to be used in the command post of his car. On the one hand, all the drivers had one because it is obligatory to drive in a car to run on the French roads, but they also make it easier for them to excel in the demonstrations and in the photos and, in addition, you can bring the slogan you want written with a marker behind your back.

Seen from this part of the sea [from Britain], it doesn't look like a very clever choice. For British activists, these jackets are the uniform of the enemy or, more specifically, that of the security guards. Here is known as “Yellow Wednesday” the forced dispersion of the Twyford Down camp since 1992, also as a consequence of the call of Drouet, organized by a national movement in that successful campaign of direct action against the construction of new highways. On the other hand, who would choose as his uniform something as ugly and anti-ecological as a PVC jacket? Soon the answer [in Britain] would come: When the supporters of UKIP [ultra-right party] showed their support in their hearings.

In addition, the mobilizations of these jackets had a striking similarity with the blockages to British refineries organised by truckers and baserritarras (as was then said with the unrecognised consent of fuel companies) 2000.ean. Its aim was for the authorities to withdraw the “Fuel Duty Escalator” law, one of the few good things the conservative government decided in 1993 to deal with the annual inflation rate plus 3% global warming. Prime Minister Tony Blair, who two years later would send troops to Iraq to protect the interests of British oil tankers, was not prepared to risk the fuel supply at home and soon gave in to the Protestants.

The rate imposed by Macron in France was very similar to that of the British years ago and Macron himself regressed as quickly as Blair in the face of citizen protests. However, even though Macron abolished the tax following the violent demonstrations on 1 December, the French Protestants did not return home. It was not the truckers or the peasants, but a mixture of ordinary people who used the possibility of protesting fuel taxes to put pressure on many other demands. They were angry because Macron had lowered taxes on megashorts and they were angry at their arrogant behavior towards the vulgo. He once called them “people that are not worth it.” Another mistake Macron made in September reminded us of the famous ‘On Your Bike’ by conservative politician Norman Tebbit in 1981, which recommended unemployed people to complain less and take the bike: “In the 1930s my father was unemployed, but he didn’t go to organize the clashes, he took the bicycle and sought work until he found it.” Translator’s Note]: recommended to a young farmer that if he wanted work, he had to “cross the road” to find work. The woman answered that she has to “overcome the mountains” in search of work.

.jpg)

It is no coincidence that the issue of fuel taxes is triggered as quickly as a protest whose iconography is so deeply embedded in the car culture. At first, the movement spread over the Internet, but in fact its image materialized in the yellow jacket placed at the command post of the cars: if you didn't have a car you wouldn't have a dashboard and probably not a yellow jacket. The site of the protest was not in the factory or in the university, neither in the court of the City Hall nor in the neighborhood itself: it was in the roundabout of circumvalations of the towns – where only conductors are seen – and sometimes in the toll areas of the motorways and gas stations. In addition to the abolition of fuel taxes, the abolition of motorway tolls between the initial demands or the rule that recently reduced the maximum speed of roads from 90 to 80 km/h.

In recent months it has been noted that people engaged in the protest are from the periphery of society, as in the geographic meaning of the word sociologically 1. In the movement are not the rich urbanites, the people of bobo [bobo: summary of the concept of bourgeois-boheme. Sociologist Camille Peugny defines it as: “A person with a non-extraordinary but good income, mostly with a university degree, who uses cultural resources and votes on the left.” Translator's note: people, left-wing intellectuals or students; neither baserritarras, who would use the barricades if they were. The Jaca de Bedarieux told me that there was not one single farmer among them: “We don’t mix them or us.” Nor were the poor low-class immigrants in the slums of the metropolis (banlieu) who participated in the destruction of 2005. One of those who had been in the city's riots told the newspaper Liberation: “Why should we help them if they have never helped us?”2.

France, “Grand Pays Automobil”

If they have a common characteristic, the people of Jaka Hori live mostly in areas that were formerly small towns neighbouring the cities and that today have become dormant neighborhoods, or where they previously had commercial or industrial activity and economic globalization has left them out. In these deserts, the search for a job often entails the need to move on a long road; and if ever the city had a center, it has been destroyed. France felt quicker and happier than any other European country with US policy. United States It's about putting on the outskirts of towns the shops that are called big surfaces here. A French professor who teaches urban planning writes:

“This has not happened by chance, it was not inevitable. In the 1980s and 1990s there was a strong impulse of the peri-urban urbanization... even though the neighbors and prey wanted to see how their municipalities developed, which meant the dispersion of the individual houses, the large commercial areas and the public services in the exterior areas of the towns. This dispersed development, which took place on a larger scale than anywhere else in Europe, was promoted by the many tax incentives granted by the urban development government”4.

In the shopping area of Bedarieux almost half of the shops are empty. All the shopping sites, including the village's largest bakery, are located outside the city and people need a car to get to them, just like the Modernist Lyceum named after the artist Fernand Leger. His closest city, Beziers, proudly shows the two gigantic shopping centers of its exterior, while the old town of its central area is completely abandoned and the idea of buying in it causes nausea.

The phenomenon of the people of Gilet Jaune reflects in part the frustration of the car culture for failing to deliver on its promises. In the words of lehendakari Macron, France is “grand pays automobilismo”. The road network in France is three times higher than that in Britain, even though its surface is twice that of the country. They have 11,612 kilometres of highways, many of them run by private companies, and most of them built after 1994: that year Britain decided not to add more to its motorway network, which does not reach 3,500 kilometres. In France, however, the average car ownership of citizens is only 9% higher than that of the British and the French only travel 9% more by car than the British.

.jpg)

In other words, the French do not use them as often as they could, and that seems to be the case because they do not earn enough to pay. According to the newspaper Le Fic5, in 2016 in France each citizen spent 6,000 euros a year in his car, which was 43% of the 13,836.5 euros that represent the minimum wage. We cannot be surprised, therefore, if the people living on the peripheries complain about the price of fuel. French governments have allowed road builders and large surface corporations to build U.S.-like infrastructure in every corner, but it would only be accessible to most if fuels were as cheap as in the United States.

In his writings it is observed that the Yellow Chaquetones are aware of this problem. Of its requirements, in the list that completes 42 in total, seven have to do with transport (in the order in the list):

- Incentivize small businesses in towns and villages: start building large shopping centres in the urban environment, so that small traders do not remain out of the market.

- Withdraw taxes on petrol and diesel.

- Halt the relocation of industries and protect their knowledge and jobs.

- Withdraw the CICE (corporate profits tax) and invest money in France to launch a hydrogen based automotive industry.

- Stop closures of public transport, post offices, schools and maternity hospitals.

- Prioritising rail freight transport.

- Tax fuel for ships and aircraft.

The role of the media

If the rebellion of these jackets is associated with some technology, it's not with the car, but with social media. Experts have attributed the success of the movement to the agile communication offered by Facebook and Twitter, the impact of the filter bubble of Facebook algorithms, or even the reach of Russian hackers. But the previous riots are not classified according to the main media they have used, be it mouth to mouth, the written press, the telephone or the email, so we must question the imputation of the current one to social networks. If the revolt had not spread beyond the Internet, it would have had a small effect.

.jpg)

In any case, the organization of the protests carried with it the dialogue between the social networks, the main media and the street, which was catalyzed by a local newspaper. In May, Priscillia Ludosky launched an on-line collection of signatures against rising fuel taxes. In five months, it didn't get much, just 700 signatures. But then the Seine-et-Marne Republik made it a hole, on October 12 he mentioned it in an article and read in the area the woman of Eric Drouet, driver of a truck. Drouet contacted Ludosky, placed a collection of signatures on his Facebook page, on November 17 he launched an appeal to mobilize and the issue became viral.

In less than a week it reached 100,000 signatures. On October 21, the newspaper Le Parisien dedicated a chronicle to the movement, and soon the other press did the same. For next weekend, according to Drouet, on 17 November, people committed to mobilizing increased from 13,000 to 93,000. On October 24, Drouet put on the internet his magnificent idea of using Yellow Jackets to express his agreement with the protest and in a few days they began to see the streets of the desks. By the end of October the famous Drouet had already been made, who was interviewed for seven minutes in the most viewed news chain of France BFM.

Mainstream media undoubtedly helped to increase the number of participants in the first protests (287,000 on 17 November, according to the government). But it is also common for the press to present spokespersons and generate leaders: in the coming weeks, as in the newspapers, several supposed TV leaders appeared, from the moderate Ingrid Levavasseur to the hardest right, such as Maxime Nicolle and Christophe Chalençon 7. Some journalists tried to introduce Drouet to hard-right men, which seemed in part, but if I was a follower of Marine Le Pen, I masked it very well, denying who voted in the presidential election, because that wasn't important.

The different political parties, aware that the mobilizations were leaving behind, joined Jaka Hori in different ways. Marine Le Pen placed the yellow jacket from the glass of his car Citroën, but it remained apart from the mobilizations arguing that "it is not the place of a leader of a political party". Jean-Luc Mélenchon, leader of the leftist party La France Insoumise, made some awkward gestures to approach Drouet, who received a negative. The CGT trade union first condemned the protests, but then thought about it better and in February organised a strike in solidarity with them8.

As for the people who have been or have been identified with the May 1968 protests, Bobo and Soixante-Huitard, who in England we would call “The Guardian readers,” many look away. These Jackets are pleased because they face Macron’s neoliberal agenda, but they distrust the clumsy character of the movement, its right components and what the Libération newspaper called “magma of Order Sapphire Salsa”.

Defending the climate, including social justice

But to what extent are these demands scum sauce? It is true that throughout the country there are many autonomous groups that are giving their views outside any central organization, but the petitions they have made public are often extremely similar and have great coherence.

Most petitions are aimed at tackling austerity and precariousness: increases in minimum wages and pensions, income control, tax increases for the rich and corporations, nationalisation of public services, combating tax fraud, etc. Some of these can be considered as green measures, such as support for household insulation and tax relief, taxation of airlines and fuel they use. Other demands tend to turn government and constitution into democratic, such as the establishment of a referendum system similar to that of Switzerland. Only a few (4 of the 42 measures mentioned) mention the most sensitive issue of immigrants.

Last April, the Assembly of Assemblies, composed of 235 local groups in Jaka, published the “Last Call” with the following applicants:

"(…) an overall improvement in wages, pensions and social services, especially with regard to the nine million people living below the poverty line. Bearing in mind the serious need to redirect the ecological crisis, we say ‘end of the world, end of the month (end of the month, end of the monde, end of the mois), single logic, unique struggle’”.

This slogan was adopted by the Assembly of Jakas Amarillo to former minister for the Ecological Transition, Nicolas Hulot, who resigned in protest about Macron's policies: “We have to redirect the anguish people suffer to end the month [to pay everyday expenses], but we also have to face the threat of an end of the world.” If at first there was any concern that right-wing climate deniers and xenophobic nationalists could take over and manipulate the campaign against fuel tax, the risk has not

materialised. On the contrary, within the movement of these Jackets it is assuming with broad consensus that climate change measures will only serve to the extent that they are compatible with social justice.

Yellow jackets and moral economy

Social researcher Samuel Hayat stresses that “what gives coherence to the movement of these Jakas, which keeps them alive, is: It’s rooted in what’s called ‘people’s moral economy’.”

Concept of “moral economy” P.V. It was created by historian Thompson to indicate the nature of the food riots of the 18th century, demanding the general public to maintain and comply with the norms related to the price and sale of bread. These riots, although they fought enthusiastically and imaginatively, had little revolutionary, on the contrary, their objective was to re-establish in the relations between classes the habits and standards that served, in part, to guarantee equity and reciprocity and that had been ruined by the force of an aggressive market economy. The rebels were progressive insofar as they advocated a more equitable distribution of wealth, but they were conservative insofar as they spoke of an already established and broken morality.

Something similar to what many Jaka Hori have: they do not agree to impose an increasing tax burden on the poorest to favor the richest, they are angry to see manufacturing industries delocalize, precarize jobs and reduce public services, while the ‘creative class’ of the bobos works perfectly. The moral economy that combines a progressive social programme with a conservative sense of culture and obligations has been what has allowed the right and left angry people to work together and cosen a coherent set of demands.

The four demands that affect immigrants, whether or not they agree with them, are also basically calls on the government to comply with its obligations. In the first two we can tell the influence of the left progressives and in the last two of the conservatives:

- The problems at the root of forced migration must be solved.

- Asylum seekers should be treated with dignity, ensuring stay, security, food and education.

- Asylum seekers who have not been admitted to the application must return to their countries of origin.

- A comprehensive integration programme for immigrants, including the learning of the French language and culture, must be put in place.

.jpg)

neighborhood in La Baule, Brittany.

However, if we analyze the set of their demands, it is evident that in them the progressive left agenda predominates. A study carried out on the Bordeaux Jackets, one of the most important centers of the movement, showed that 42% were from the left, 12% from the right and 33% without political affiliation9. It can be thought that the left-wing elements of the movement are better articulated politically than those of a right-wing agenda. Consequently, although the right-wing view of some of the leaders exaggerated by the media is full of concerns towards immigrants, nationalities, etc., most of the demands that the movement has presented are progressive. As academics Sandra Laugier and Albert Ogien have written in Libération, leftists Jaka Hori “since their political commitment, have contributed to the formation of a list of political demands (wages, tax justice, direct democracy, etc.). which have managed to entrench the xenophobic, homophobic and authoritarian tendencies present in the early stages of the movement”10.

Looking from England to these Jackets

It is fashionable at this time to say that the old differences between Left and Right in politics are collapsing. This seems to corroborate Jaka’s rejection of his political parties and that, like Le Pen, Melenchau has failed to take advantage of the movement. The revolt in these Yacarés has meant that their left-wing and right-wing forces have joined in a rather coherent programme of resistance to neoliberalism and austerity, and that they have called for fair application of fiscal measures to channel the environmental crisis.

But that does not mean that on the one hand the currents of nationalism and on the other the currents of anarcho-socialism go as one line. Under the yellow PVC varnish, they remain variable. A request for a referendum such as that of the Swiss can be turned into a markedly democratic appeal for policies against refugee mares and freedom of movement in Troy, as has already happened in Switzerland. It may also be the case that the Frexit – which France leaves the European Union – is being strengthened, which already has many supports among the Yacarés carrying a tricolour flag, although this objective has been considered too “political” to include it among the demands.

In Britain, which has already split Brexit into two, there are very few possibilities to create a left and right front against austerity and neoliberalism. Surely it is not going to happen that the Protestants have similar colors to those of the anti-rebel police and guards of seguridad.Pero the British have much to learn from the path that these Jakas have torn in the right direction. Anti-fascist protests against the purposes of Tommy Robinson, an ultra-right-wing and well-known British Islamophobic asset, barely manage to curb the rise of right-wing populism, and may even aggravate it. It would be better to ignore him. A more hopeful step forward would be for the misled to move towards a non-partisan platform for economic, fiscal and environmental justice.

This is particularly true of the environmental movement and supporters of Extinction Rebellion, many of whom are young bobos. The handling of climate change, with the remaining time, will require the Spanish Government to adopt austerity measures in the face of the crisis. If your burdens fall weaker than they are proportionally, there will be a great likelihood of strengthening an opposite right-wing movement, in line with Trump.La alternative is a broad popular front ensuring that the richest consumers will be first and the most charged in the name of environmental justice (in other words, the proportional distribution of burdens). We have a very long road ahead, but the Jaka Zure movement gives us some hope for the way in which they have tackled these issues.

.jpg)

1 In the analysis of the role of the peripheries I owe a lot to Christophe Guilluy, author of the book No Society. See C Guilluy, ‘France is Deeply Fractured. Gilets Jaunes are Just a Symptom’, The Guardian, December 2, 2018.

2 Cited by Jeremy Harding, ‘Among the Gilets Jaunes’, London Review of Books, March 21, 2019.

3 In the Ile de France region, which covers the Paris area, Eric Drouet and Priscillia Ludosky spend 75 minutes a day in the car, while the people in the countryside spend 45 minutes. Enquête Nationale Transport et Déplacements, 2008, cited by Aurélien Delpirou, ‘La Teinte des Gilets’ in J Confavreux (ed), Le Modem de l’Air est Jaune, Editions du Seuil, 2019.

4 A Delpirou, ibid.

5 C Maligorne, ‘Ce Que Vous Coûte Réellement Votre Voiture’, Le Figaro, 29 March 2018. The cheapest car analyzed was a diesel Dacia Logan, which costs 4,900 € per year.

6 F-B Huyghe et al, Dans la Tête des Gilets jaunes, VA Editions, 2019. Rhys Blakely, ‘Russian Accounts Fuel French Outrage Online’, 8 December 2018.

7 Ingrid Levavasseur temporarily stood in front of a list of Yellow Jaca proposed for parliament. Maxime Nicolle became popular with his racist proposals. Christophe Chalençon has been a right-wing candidate in several elections and in January he met with the Italian populist deputy prime minister, Luigi Di Maio.

8 ‘Gilets Jaunes au Bout de Souffle’, Aujourd’hui en France, 23 February 2019; Le Journal des Gilets Jaunes, No 1, February-March 2019.

9 F-B Huyghe et al, op cit 6, p 31-2.

10 Sandra Laugier and Albert Ogien, Un Gilet Jaune à l’Elysée? Libération, 13 December 2018.

Herria eliteen aurka. Edo beharbada errealitate konplexuagoa, historiaren barrunbeetan sartzen zarenean. Horrela islatzen dute Éric Vuillarden liburuek. 2017an Frantziako letren saririk handiena, Goncourt saria jaso zuen L’Ordre du jour liburuarengatik.

The movement of the Yellow Vests, as soon as it was lifted, was condemned to shut down. There it goes. It seemed that I would get nothing. Because he rebelled against a simple tribute? Or because it didn't pose a serious redistribution of rewards and riches? Now the discourse is... [+]