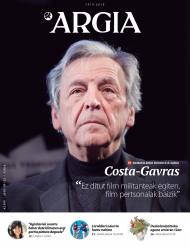

"I do the show, but it cannot be empty of ideas or thoughts"

- The French director of Greek origin Costa-Gavras will receive the Donostia Prize of the San Sebastian Film Festival this year. It is a recognition of a whole trajectory, from the mid-1960s to the present, to film production with a critical perspective. The last time a public event was held in the Gipuzkoan capital was in 2016: The Basque Filmoteca organized a colloquium with him and Imanol Uribe. In this interview prior to this act, in addition to commenting on some of the most important films of his trajectory, he referred to his personal way of understanding film.

Since his first films in the mid-1960s, he began using the thriller formula, which many interpreted as an American style. This contradicted the demands of a militant film of the time. For some people on the left, this kind of film was a retriever, a product of the capitalist system. How would you respond to this kind of criticism?

As for the police architecture of films, Edipo is the inventor of it, Sophocles. Edipo is a black gender story: it comes, it happens what happens to you and then you know it; and we want to know what happens next; and until the end, until Colona, she asks “how is this possible?” So, I don't think anyone has invented that in America ... If you take the films of the cowboys today, they are built just like the Greek tragedies. Three parts: first, second and third.

Take L’Aveu (1970) for example. The story begins as a police officer, “what’s going to happen to you?” and so on. And then, at a given moment, we stopped the movie. We say “look, live, it’s there, it’s very good, it’s handsome.” And from there, it's necessary for the audience to continue with the story. Will it live or not live? But more politically, I understand what happened to him and why it happened to him, who did it, why, etc.

With regard to the aforementioned debates, their choice caused problems in left-wing environments, because they detected it ...

No, that's what he did -- no, there's a difference. That word you mentioned, a “militant” movie. I don't make militant films. I make personal films. The first thing you have to define is what a militant movie is: that's if someone decides whether they're going to make a movie about an idea or about a group, about the ideas of that group. It is not, therefore, a film that comes from it, even though it has done so sincerely and sincerely. It's not your personal view. It explains the view of other people, of the communist party, of the X or Y party, of the church, whatever it may be. That is “militant,” putting it at the service of something. And I don't serve at all. I tell a story. I do a show. I want to repeat that point: I do the show. And in this spectacle I have to bear in mind that the spectacle cannot be empty as far as I am concerned, that is, it cannot be empty of all ideas, without thoughts, without thoughts.

"Cinema can change the

world, but

not a film or two films: cinema as a whole can generate questions, provoke reactions and show things"

In a slightly in-depth analysis of his work, it seems that categories such as “fiction” and “documentary” are not correct. They don't address the complexity of their work. What do you think of the tension between historical documentation and fiction? How can we reconcile these two things?

To make a documentary you have to have images, but we don't always have images. This is a very general consideration. And furthermore, we try to be as close as possible to the “truth” with a documentary – I put the truth in quotation marks, because we tell the truth that has happened in six months or three weeks in two hours, right? Another thing about the documentary is that we talk to people who tell the story, so all of these features make the public of the documentary generally very limited. In addition, it's an impression we have, which is a concrete story, no metaphors, no extension. And fiction gives you the choice to open it. For example, if we had made a documentary, we would say that this is happening in Greece, in this environment, at this particular time, etc., under these conditions. Well, we didn't. The viewer must participate, try to understand, so you have to create a kind of relationship with the viewer and the work in the first place. And the other thing: the mechanism that we're showing is not just a Greek mechanism, but something broader. In a film like Section spéciale (1975) there are much broader mechanisms and fiction is the one that gives the option to do so. The documentary can also give it, but how to reflect on it. Fiction, which, I insist, is a spectacle, generates absolutely particular feelings towards the work, the characters and the actors.

We want to ask you about your position as a deportee in France. You were in a foreign cultural space, and that allowed you to make a film like Z, explicitly critical of Coronel's dictatorship.

My generation escaped from Greece because it was part of a class that had no rights and no future. The only way to try to have a future, as in the case of those who are now leaving Africa and around the world, was to study outside. And that, for free, could be done in France, because you had to have a lot of money in other countries, in England, etc. In addition, I had tremendous luck, because I fell into an environment that accepted me, in France -- [Yves] Montand, [Simone] Signoret, Chris Marker, Michel Foucault -- in the midst of all those people. And I learned life differently, also politics.

But at last I felt Greek, I wanted to try to explain in a different way what had happened since the colonels took power in my country. I was angry because I said, "This is not possible, this country, like that." And Z is made of that fury in that direction.

.jpg)

In Section spéciale you touched on a rather serious issue in France [the film shows the attempts of the Vichy collaborationist government to create an ad hoc law to punish six French people after the attack on a German official].

For the foundations of France, yes.

We could say it was a kind of social taboo.

Yes, absolutely.

Do you think your Greek position gave you the opportunity to touch that sensitive material?

Possibly the presence of French people on the team also helped. To understand this, we have to understand how French cinema was made until a certain time. It was done by the children of the high French society, that is, the upper-middle classes. Why? Because to make a movie, you have to wait, learn, have knowledge, take time to write, all that. And -- you can't work every day and make a movie at a time, you know? That changed a lot in the 1970s and 1980s, a lot of people were introduced into the movies, the French system gave them the opportunity to do so. It is therefore true that at the time when I made the film many preferred not to touch these kinds of issues, in general. Or they touched them, without a direct mention. But something like Section spéciale probably wouldn't.

Do you still think film can be a means to change the world?

You can change it, but not one or two movies. Cinema as a whole can generate questions, provoke reactions, show things or interest history. But it's not cinema that brings him to the end. That is impossible. But it is clear – and I repeat this always – that all cinemas are political. Well, Barthes said that, Roland Barthes: “All films are political.” We can look at all the movies politically, or, which is the same, there's politics in all the movies.

"The spectator has to participate in the film, try to understand it and to do so we have to create a special kind of relationship between it and the work"

With Le Capital (2012) it seemed to us that he tried to face the structures of capitalism, which was an attempt to break the logic of depersonalization used by the system. Do you agree with the definition?

Yes, yes, and I'll come back to the question you asked me earlier. There, cinema plays a role, because it puts a face, it puts people. You see in that case the men who rule the economy. There are men who previously, also in L’Aveu, study other men and make other men speak. It's not just a system. Therefore, in today’s economy we know that there are links: there are banks and there are bankers. There's something we don't know, which I found in a French book, by a large banker, [Jean] Pyrespade. His book Le Capitalist Total (Total Capitalism). Among other things, he says that democracy is a local placebo in the opinion of big companies. It says that the bosses of the big companies, those faces that you spoke to, if it's not the shareholders who distribute the dividends that they want, throw them away for others to grab them and do their work. That is what it clearly says. He continues to say that today money is used to make more money, but not to create goods for society. And what he says is a banker, not a leftist. So, cinema can present this kind of thing, it can prove it. With some difficulty, you have to find the story. And this story has managed to synthesize it, which is not easy to find.

Since you made the first film, your film has polarized the audience a lot. There are people who have supported you a lot, but also people who have criticized you a lot.

Testers.

Why do you think this happens? Because is it a film that tries to take a moral position?

Because unanimity never happens in the movies. Maybe in some movies, like Gone With the Wind. And many more. But I believe that the films I have made cannot achieve unanimous applause, so I cannot fail to do so.