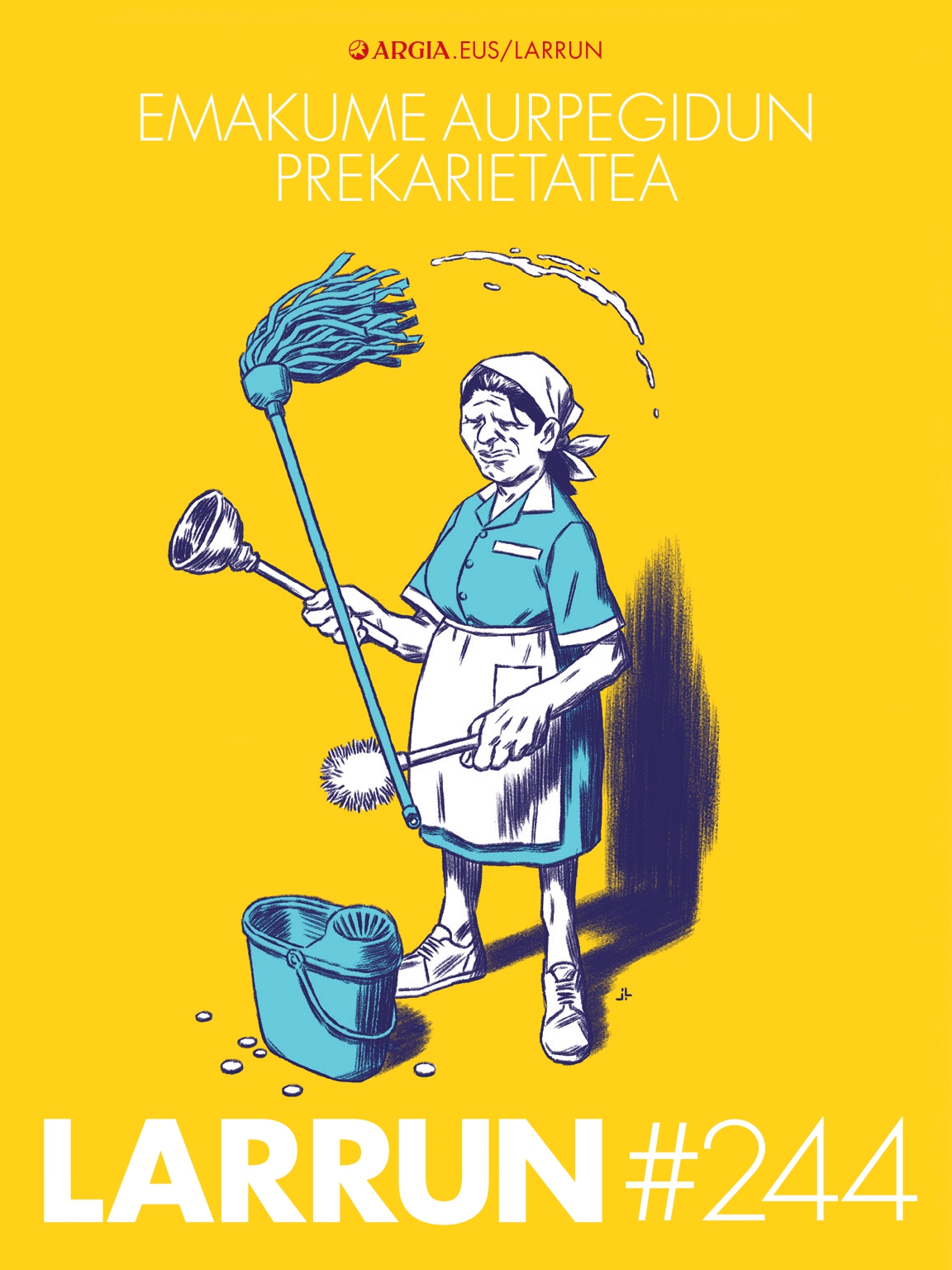

Precarious people raise their voices

- On 27 March, as part of the commemoration of the centenary of this media, you will have a paper round table “The struggles of care workers” organized by ARGIA and the Manu Robles-Arangiz Institutua Foundation. In order to talk about what should be collective but which is generally supported by less privileged social sectors—precarious, or precarious, and migrant women—the topic of care was raised at the Kafe Antzokia in Bilbao that night in March.

As diners, women who are dedicated exclusively to care (a household employee and a head of nursing homes) or those who, indirectly, work in the sectors that go through the care tasks (a hotel cleaner and a baserritarra) were invited. Particularities of the sector of each one of them, the four precarious, working women and in two of the cases because they are migrants; the four women who have come out in the street in defense of their rights and in struggle for social transformation; those who, beyond breaking the glass ceilings, are also giving us a thorough review of the viscous soils of the labor market.

The need to put life at the center and to collectivize the responsibility for the care tasks was valued in the feminist strike of March 8, and it is not surprising that on that occasion the Feminist Movement of Euskal Herria said that in order for feminist transformation to occur, conflict is necessary, “especially in those areas that have been left out of the political conflict”. One of these areas is care, and the roundtable summarized on these pages is one more step towards politicisation, not of all kinds. This is illustrated by the content collected on the pages from the speeches of the four rapporteurs.

In conclusion, the reading has also been divided into two parts: in the first part the reader will find a conversation with the members of the table Soraya García Pablo, Silvia Rugamas Rivas and Arantza Arrien Goitiandia, while in the second part the conversation held with Elena Vasconez Cevallos, fourth vowel. In both cases, journalist Onintza Irureta Azkune is a moderator in this house.

Onintza Irureta: What is being precarious in your sectors?

Soraya García: I say that the precariousness we live in the residences of Bizkaia is the most typical of the typical. It is a sector of high temporality in employment, which generates tremendous insecurity in women on temporary contracts. Furthermore, contracts are formalised in legal fraud, mostly in the area of partial activity. In a group of women who have spent little time in the labour market and are over 50 years old, part-time working days mean that they will come to retirement with the minimum contributions and that they will suffer the same precariousness as they are today. On the other hand, there is a sector with a great physical and psychological overload due to lack of personnel, and the schedule and shifts make it extremely difficult to reconcile work with the family. As for wages, they do not give enough to meet basic needs, and I am not just talking about housing, food and clothing, but I am increasingly concerned about an unusual type of precariousness, more linked to the personal aspect of life. In fact, the lack of satisfaction of our personal needs causes marginal damage to our social needs: if we cannot meet the basic needs, the less we will be able to meet those related to leisure. We will not be able to take any courses in order to achieve a better working situation, we will not be able to spend money on cultural events, or make great trips. It is a precariousness that I find very worrying, which in the case of women leads us to isolation, to a shorter social life and to lower self-esteem. And those are the main problems for women. Working women are becoming more and more aware of job insecurity because we make our working conditions visible, but we often forget about that precariousness and I think that it is important to be careful. The social isolation and the loss of self-esteem generated by this precariousness often lead us to difficulties to move in the labor world, feeding the role of a submissive woman, without friends and without culture at home. In my view, therefore, economic precariousness in the world of work affects both social needs and basic needs.

Soraya García: "The lack of satisfaction of the personal needs we have generates lateral damage to our social needs: if we cannot meet the basic needs, we will be less able to meet those related to leisure"

Silvia Rivas: I think precariousness has a female face. Poor, migrated, paperless, isolated woman with few resources and tools. Six decades ago, impoverished women from the Spanish State came to work here, who were given the name of maids. For now we, women from Latin America and Central America, are dedicated to care, to sustain life. We are new servants. We will only have one option: to perform care and care tasks, either inside or outside the house. And we who have papers, if we live in a double precariousness [for being a woman and migrated], think about the situation of undocumented domestic workers who spend 24 hours a day in jobs that no one inspects. All rights are violated: they are not entitled to unemployment benefit, nor to an inspection that controls the work they do at home. Consequently, many women suffer abuse of power, emotional blackmail, sexual assault. And what about the women who are in these situations? Because they're alone and they don't have paper, they just have to devour the situation because they're afraid. Because they have to sustain the lives and lives of those who have left fear in their country, and that drives them to withstand these different subdivisions and labor violence. There are women who have told us that they sleep in the same room or bed with the person they care for, and beyond care, they have to do various tasks like cooking, washing clothes and sanding. Most contracts are based on lying: They tell you “this we will do to you for social security”, but in the contract there is no record of a 40-hour working day, they put your hand on the day to day, until you double your obligations.

In addition, we have the Aliens Act, which puts us under the umbrella of multiple violence: they ask us to live three years to regularize our situation, and that is possible if you find an “honored” employer willing to hire that allows you to obtain the regularization card. Otherwise, it can still be paperless even if time has passed. However, when you get the papers, you realize that the situation only changes a little, you feel a little freer, but the precarious situation is similar. There are women who work 14 hours a day and who have neither social nor family life. They have burdens, diseases that no one recognizes, like depression.

Silvia Rivas: "When you get the papers, you realize that the situation changes a little, you feel a little freer, but the precarious situation is similar."

Arantza Arrien: This is a masculinized, non-feminized agricultural sector. We think that the oppression of all kinds that we live today comes from where patriarchy and capitalism converge, and in our case that happens when the agro-industrial system is put in place and imposed afterwards. This industrial system has brought about a radical change in our relations with work: industrial agriculture is that of men and women working for them; for man, for business or for the system. Because today power is in money, and whoever has money has the power to decide. This system also implies the elimination of collective working spaces and the implementation of a great individualism in agriculture. Before, it was not possible to work a single person in the dwelling, that is not the nature of our work, but today in most farms we only work one person, with all that means: it means isolation, and it means that it is encouraged to go to the city to look for another kind of work; it also increases relationships of dependency and we have more employers. Although we believe that what we consume is freely chosen, however, at the same time as they tell us what to consume, when and how, they also instruct farmers what to produce and how to do it.

Our precariousness has mainly to do with the following things. In this monetized society, money is one: our average economic remuneration is below the interprofessional minimum wage, we are the majority who charge below. Money says who can be the land at the moment, who has the right to exercise this profession. And it is clear that this cannot be the case, that the main obstacle to food creation cannot be money. On the other hand, there is a distribution of aid: A significant proportion of European budgets are taken by agriculture, and 20% of people receive 80% of the money; women receive 32% of the aid and men receive 68%. Considering the average amount charged per person, women charge 55% less than men. This is particularly true of our agricultural model. In addition, it must be borne in mind that in agriculture we are two types of workers, although some are considered to be entrepreneurs: self-employed workers and wage earners. The salaried staff is a feminized sector, with dire working conditions: some are forced to wear diapers so they do not waste their time urinating; and there are also cases of seasonal workers joining strawberries in Huelva. It's often thought that we're self-employed all the farm workers, but there are a lot of salaried people, and a lot of them are migrants right now. Apart from all this, it must be borne in mind that, particularly in the case of women, many of us do other work apart from taking out a small salary and meeting expenses. And women are also affected by another kind of precariousness, that of time. As we usually work back home, we do not have a fixed schedule and the productive and reproductive jobs are mixed: at the same time as it turns on fire, hangs the clothes, takes the grandmother to the doctor and practices the leeks. We therefore believe that we need time to enjoy, rest, militate and implement other alternatives.

Soraya and Silvia, why do you think you are working in worse conditions than the masculinized sectors and the male workers of your sectors.

S. García: As we have been saying throughout the conflict and the strike, because we are women who are going through what was going on. With our work it happens that these are jobs that women have done throughout history to fulfill the role of women. Care work has come to the market because we live in a model of society that privatizes services such as elderly care, as well as public money. It has become a big business for companies. And also, how lucky, women do these jobs, because they're what they've done all their lives and they've done very well, and if we give them a little bit of money for what they've done so far, this is the business of the time [ironically]. The jobs we perform women are not given any value, it has always been so, when women worked at home the same, they were not given any value. I have always said that they do not regard us as working women, but only women. Our work does not have enough recognition to have an economic value that allows us to live from our work. Our work is the prolongation of the role of woman that drags us in time, machista society assigns us certain jobs since we were born.

S. Rivas: In our sector, there are male caregivers who do fulfil the role of auxiliary caregivers. The people they care for are taken to the park or to have coffee, but they don't do the homework and employers don't lend them to work at the neighbor's house, their cousin or their aunt's. For women in foster care, this is hard, because we see that women are always given the easiest jobs, while women are added to work at all times. Not only that, but men are also paid more, there are big differences between the salaries of men and women who care. There are also men who are guardians inside the house, but there they are also dedicated to custody and assistance, not to housework. I would say that in some of the houses where there has been a male, they have rehired the female caregiver so that she can also do the housework.

Silvia Rivas: "Male caregivers do not do household chores and employers do not lend them to work at the neighbor's home, their cousin or their aunt"

And you, how would you explain the difference between Arantza, the woman and the baserritarra man in terms of precariousness?

A. Arrien: I mentioned aid and paid work. In addition, there are a lot of women working in the farmhouse, although they don't see anywhere. So many invisible women as active women work in this sector. The main reasons are the small economic benefits and priorities: in many cases the purchase of a new tractor or any other in exchange for the woman’s contribution is premium. In professional holdings, 58% are male holders, 25% are female holders and 18% are female members. The oppression of women from the agricultural system is what characterizes our agricultural model, as I have already mentioned. 58% of the women in the workforce work less than two hectares. We don't go anywhere, and everything is an obstacle. What if I make eggs, juices, vegetables, fruit,…? Well, I need an installation to make juice. Today we know what any work means, and furthermore the health system – I mean the one that controls food – fulfills a number of requirements: everything is panels, all doors and sinks. It's very expensive. I would have to make an investment in order to be able to register myself: we will sign with the premises, some EUR 50,000, and I am not going above that. Suppose that in addition to juices, I want to produce eggs: I would need another room to do it, and one more room to store the packaging. If I wanted to jam the same way, I would need another place. Furthermore, what is being promoted is the personal construction of all these works and infrastructures; the existence of groups is not being defended at all. That is one of the struggles we have at the moment: to accept the collective workers. We believe that it would be much more sustainable and enriching both for the situation of women farmers and for the system we have, as it would mean a significant improvement in conditions.

Arantza Arrien: "So many invisible women as active women are working in this sector"

In addition, there is another difference in representation between women and men in agriculture: the agricultural political bodies are completely masculinised. Cooperatives the same, and unions too. And that's what happens to us in all the structures of the primary sector. In addition to all this, as I mentioned before, most women farmers do some complementary work, because this other work we do outside, in most cases is related to care, in school canteens, etc.

As before, in three out of every four sectors you are here, you perform care and cleaning tasks that are still considered as women's tasks. Do you think your work is not valued?

S. García: The jobs that women have historically done at home have gone out of the house, but women continue to do so in a precarious way. Therefore, it is no coincidence that in the labor world the roles we have been playing for a long time are fulfilled: cleaning, care, housework, children… As it is no coincidence that precariousness is today a woman’s face.

I think it is clear that women have ceased to be silent and defeated, as we said during the strike “we are not afraid and the silence is over”. As all this went out into the street, it can be said that she has begun to talk about the work of women and about precariousness with the face of women. But this is not new, nor is the strike of yesterday or of the old people’s homes in Bizkaia, which comes much further behind, since women did their homework for free, without anyone looking like anything else. These women were so subjected that they could not take a step without their husband because they lacked wages. If on the street conflicts have become visible, people have started to take into account the women who protest, if women have come together and we have started fighting, one thing is that women have put themselves on the idle: that the most precarious jobs are those of women and that they are directly related to the jobs we have done historically in our homes.

S. Rivas: I believe it is high time that care ceased to be the work of poor and migrated women. In my opinion it is important to socialise these works, to make it clear that it is also the responsibility of men and that they must also be mixed up. It is enough for women to deal only with care, it is enough to put roles from the moment we are born. It seems that we only serve to clean and care. It is time to reflect and develop the social awareness that we have to share the care tasks, so that public institutions, as it is time, intervene in this matter and exercise control over them. Because the in-house worker who is going to perform these tasks is also worth resting, you cannot afford to have the burden of custody 24 hours a day. In my opinion, domestic work is the most precarious, the most invisible, the ones that have not been recognised. More and more is being said about the subject, and we are naming the work. Well, I think there's time to join and fight. So let's go on.

.jpg)

Arantza, the baserritarra does not focus on care, but do women farmers have more weight than men in caring for the house and their relatives?

A. Arrien: Yes, no doubt. It's not our axis of work, but care is part of our work. We have peculiarities in relation to the urban centers, and that is that we live on the margins of the people. That is why we have a transport load that is added to us when we have to walk from one side to the other. On the other hand, we have cleaning things, because we live in big houses, and we have blocks, and we have a pavilion, and extraordinary upheavals. In addition, we have other care directly related to our work, which are feminized: making preserves, keeping seeds, collecting different herbs... for example, if we need camamil for the whole year, the woman collects it. Work like this transmission of knowledge is another kind of care. Faced with all this, we have an advantage, and that is that in small towns we have a great potential to generate social care, both due to the same need and the situation.

You have many years of experience in your work. Has the situation of working women improved in your sectors?

S. García: Our situation has improved and much improved. It is clear that if it has improved it has been through organisation and union within companies. We women have realised that the people responsible for our working conditions are ourselves, that we are the ones who have to take the lead and fight, and that we can fight it through organisation and union. The situation has changed dramatically: In 2003, the Bizkaia housing agreement was initialled by the Spanish State Agreement with a profit of EUR 632.77 and we have achieved a salary increase of more than 200%. We can therefore say yes, that the situation has improved a great deal. During all these years we have had to go on strike and fight for all the agreements, and we have not seen any setbacks, because we have not recognised them. If so, I believe that we have improved a great deal and that we have much to improve. We've all internalized that it's possible, and the struggle has empowered us a lot: in these kinds of conflicts, when you know what your job reality is and you know it's up to you to change the situation, when you feel part of a group, you're empowered, which tells you that you're capable. You're aware that you're able to get what you have in your hands, that helps you deal with fears and insecurities, and it encourages you. Many of us have lived through this process throughout the conflict and it has given us enormous strength. So, yes, our situation has improved a great deal, and it is worth it. But the organization, the unionization of companies and the struggle are essential on the road to victory. We have therefore won.

Soraya García: "When you know the reality of your work and you know that it is up to you to change the situation, when you feel part of a team, you are empowered."

S. Rivas: I have been working as a guard for twelve years and I do not see that the situation has improved, quite the opposite: we are becoming more and more precarious. Until the situation is regulated and convention 189 is legalised, I do not believe that we will see any improvement [refers to convention 189 on household tasks of the International Labour Organisation, that if it were adopted there would have to be legislative changes, especially as regards social security]. The sector and labour are not regulated. At all times we have remained in this special scheme, and we are not entitled to unemployment benefit or reduction, nor to the inspection of the work we so badly need. In this sense, I feel discouraged, but I also know that we have made progress on many things, since at least the care has been put at the centre and the subject is discussed. In this sense, the situation has changed for a few years: two years ago, I participated for the first time in the feminist strike on March 8, and on the part of feminist groups I felt the openness to work on care work. Because it was thought to be important, then we started talking about it, and then we started taking our demands to the streets. I participated in mobilization, in the axis of care, and since many women home caregivers could not be there, we were spokesmen. We recorded audios with the voices of women who couldn't be there to take their presence to the street.

There's still a lot to do, there's a lot of consciousness to work, and only we can't, we need help. The tasks of care are transversal, they affect us all, so we should become aware and give way to collaboration and alliances to keep fighting and achieve the regularization of this work. Like Soraya, we have managed to say that we are ever here. But if you do, it will be in a group and through alliances.

A. Arrien: The group of baserritarras women is increasingly diverse. New people are being incorporated and with it other perspectives and forms. This has been an improvement for us. On the other hand, we have also worked with other groups, such as the equality technicians of some municipalities, and from there we also perceive an improvement. Subsequently, a legal figure of co-ownership was created that regulates the management of the exploitation in case the heterosexual couple worked in a farm and that allows a compensatory pension for women in case of distribution. Another legislative change has been that of the Statute for Women Farmers, which gives opportunities, although as always happens, if you do not put in human and economic means, it is little. At the moment, the Basque Government has sent a letter to all the agricultural groups in which it states that in all the bodies 40% must be made up of women and that if this measure is not complied with, they will not be able to access the aid. It has started out there, it has great potential, but for the moment we are in it, even though there is something. If we have not made progress at all, it is in the recognition of our work model. Research on our model is not encouraged, everything is directed at other models, technology and research are far from women in agriculture.

We can see that street photos are changing: we're seeing working women on the street, fighting for their rights. Do you think you've managed to bring your struggles to the front line?

S. García: Well, we've managed to socialize and make our work more spectacular, but it's for the work we've done, of course. We have had to do historic work. The conflict has been socialized leaving every day to the street – from there 368 days of strike, that is the task of visibilization – going from town to village, explaining our situation in all the places that invited us. In addition, we have strived to bring the maximum number of collectives and create alliances, because it was clear that it is always positive to join with the feminist collective, with Pentsionistak Martxan, with Babes Uz, with the association of families of residents… All these sums made the conflict more and more visible. But behind there is a whole process, a process that includes many assemblies and that requires the participation of other collectives with you.

The struggles are present because we live in a situation that only requires struggle in the workplace, we have to go out in the street because the work situation we live in is painful. The precariousness in our sector is getting worse and worse, and if we do not fight, if we do not bring the conflict to the streets and do not let people know what happens to us and we charge, society will not be aware of the situation and will not help us, we will not achieve anything. But, I insist, the conflict has become something spectacular because we have worked to make it that way. Society, employers and governments have not cooperated. The workers have made the conflict visible, and the associations have wanted to listen to us and help us. And in our case, the support offered by the ELA union through the means made available has helped us to bring the conflict to the streets.

S. Rivas: I also believe that the collectives, increasingly, are willing to do something to make our work visible. The nice thing is that houseworkers are the protagonists of this work to make the conflict visible. We are currently working on an awareness-raising campaign in which the protagonists are the domestic workers themselves. This is a campaign that will be visible at all the stops and in which you will see the faces of the women who take care of children and the elderly and clean their homes. It is a way of questioning society, making the theme visible and socializing. I think we will move forward as a turtle, little by little, but we will come to say “we have achieved it”. It's important.

Arantza Arrien: "Our proposal is to impregnate with feminism the food sovereignty and feminism of food sovereignty, and as far as we are concerned, it has made it clear to us that feminism has also claimed food sovereignty. On the other hand, we go slower: we wear our feminism sector, we go harder"

A. Arrien: To start with, thank you and congratulations ARGIA, because these kinds of things make us more visible. Our proposal is to impregnate with feminism the food sovereignty and feminism of food sovereignty, and in what has made us see that feminism has also assumed the claim of food sovereignty. On the other hand, we go slower: we wear our feminism sector, we go harder. I would like to comment that the precariousness of our trade affects us all, because we all eat and the consumption habits of all affect our situation. We are all baserritarras, as we say. Given our responsibility for climate change, we say that we are part of the problem, but also of the solution. And in relation to precariousness, I would say the same thing: we are all responsible, but the solution is in everyone’s hands.

You, Elena, left Ecuador in 2003. Why?

Elena Vasconez: Like many other migrants, I fled my country in search of a better life for myself and my daughter and my parents. I left my four-year-old daughter to give her a better future. Imagine what it's like to lay off a child for months or years, if we go out with a bad body when we leave it often in daycare for a few hours. Two years after my departure I was able to take her with me.

In 2003 he moved to Valencia. What jobs did you do there?

R. Vasconez: When I arrived in Valencia, I got my first job as a home worker, looking after an older person. In that work, I spent my time until the death of the person I was caring for, who was in his last days. I also worked on childcare, field care and cleaning. That's what's out there, without papers, it's hard to find anything else, and you accept the first job you often find.

You spent a few years in Valencia and came to Euskal Herria, thinking that here the working conditions would be better. What did you find?

R. Vasconez: Well, the difference was big. Here you pay a little more for the work, but of course the expenses for rent, food, etc. They're also older. It is true that here I have met very nice people, with whom I have worked for a long time. Much better than in Valencia, to tell the truth.

What work has he done here?

R. Vasconez: The same ones I did in Valencia. I've done cleaning work, I've looked after the elderly, I've looked after the kids -- I've looked after a child from 8 months to 5 years old, it's a young day, we see each other and she loves me a lot. I got papers through an employer’s contract and started to have a slightly better situation: I went on to pay, which brings some benefits, such as unemployment benefit and social security.

I have heard you say that racism and xenophobia are everywhere. Have you lived it in your skin?

R. Vasconez: In jobs, I have not experienced any of that, because, as I said, I have found good people here. But in public space, yes. Once on the subway, the next thing happened to me, when I was pregnant: a woman recriminated me that I was sitting in the subway seats, and it wasn't, because I was sitting as I could and for seven or eight months. In addition, people say that we come to steal work, to ask for subsidies and others; but that's not the case, you don't have to generalize, because many of us work honestly, maybe we do jobs that the locals don't want, so that our children and our families can go ahead.

Let's talk about his last job: hotel workers have gone on strike.

R. Vasconez: We stayed for a while inclining, simply accepting what was given to us. We were paid 2.5 euros for each room washed and we often had ratios of eighteen rooms. If we didn't come to settle all these rooms, we were paid for the rooms and we had to sacrifice a day of rest to pay off the debts. All this in order to achieve a salary of EUR 800. Faced with this situation, many of us spoke in the corridors, we wanted to unify, but nobody dared to do so for fear of losing their jobs if they complained. A lot of people struggled to make the decision and go on strike, but all of a sudden we took a big step. We've been on strike for 47 days, we've got a lot of improvements, but we're still fighting, because the company is denying us a lot. Even though there's a chord, we're still in it.

You've premiered on strike as a union delegate. Why did you decide to take this step?

R. Vasconez: As has been said, many colleagues are afraid to complain. In addition, there are a lot of foreign people at the hotel who find it very hard to discover Spanish. If so, I may speak and understand better; I have often given explanations to others. Maybe that's why I've been supported as a union delegate, because they've found that I have communication skills.

I have heard you say that migrants work in worse working conditions than indigenous people.

R. Vasconez: Yes, I think that's because migrants always think we have to lose. “I’m working, where will I go if I leave this job? What am I going to work on? I can’t work in a company, I can’t pay, I won’t have benefits if I stay unemployed,” he thinks when he works without papers. Therefore, people who do not have papers have no choice but to accept what is there. Natives don't have this, if they're comfortable at work and they like what they do, they're still there, and if they don't quit the job, because they know they're going to find something else.

You don't work all day long, even if you told me you had to do it yourself. Being three children, the reason why we do not work all day is conciliation?

R. Vasconez: I cannot work full time, because I have three children. Although my oldest daughter is 21, I have two young children. And as you know, we women work at home as outside the home: it is our responsibility, in addition to work outside the home, to take care of children and domestic work. If the children have to go to the doctor, if they don’t have school… I have to organize myself. It doesn't allow me to work full-time. We are paid for the work we do outside the home, but not inside the home.

Women in precarious jobs are going to the streets to defend your rights. You are more and more showy, both you and your labor conflicts. Do you also live?

R. Vasconez: Yes, we are increasingly making ourselves known. We are in this struggle to be valued as women and workers. That is why, at the feminist strike on 8 March, we went out into the street to claim our rights. We must continue to fight, not everything ends here, there is a long way to go and we must move on. As a friend said: we must love ourselves, from respect for ourselves, so that others respect us and value us.

VOCALS

Silvia Rugamas Rivas (Household employee)

Born in El Salvador in 1977, he has resided in Euskal Herria since 2007. She is domiciled in Santurtzi, and that of the household employee is an office. Since he migrated he has not changed his profession, he has cared for the children, first without papers and then in regularized situation. She is a member of the Association of Non-Domesticated Workers (Non-Domesticated Workers), which emerged from the Schools of Feminist Economics of Euskal Herria. She works as an out-of-home worker, but she also knows the reality of women working as domestic workers.

Born in El Salvador in 1977, he has resided in Euskal Herria since 2007. She is domiciled in Santurtzi, and that of the household employee is an office. Since he migrated he has not changed his profession, he has cared for the children, first without papers and then in regularized situation. She is a member of the Association of Non-Domesticated Workers (Non-Domesticated Workers), which emerged from the Schools of Feminist Economics of Euskal Herria. She works as an out-of-home worker, but she also knows the reality of women working as domestic workers.

Soraya García Pablo (Senior Nursing Home Worker)

Born in 1968, he lives in Etxebarri. She is considered a feminist and a trade unionist. He has worked as a  manager in the residential network of Bizkaia for eighteen years, thirteen of them as a union delegate of the ELA union and in recent years as a full-time liberated worker. He has been at the negotiating table in four of the five agreements in the residential sector of Bizkaia. The strike began in March 2016 and was on the front line until the negotiation of the last convention that was held until October 2017.

manager in the residential network of Bizkaia for eighteen years, thirteen of them as a union delegate of the ELA union and in recent years as a full-time liberated worker. He has been at the negotiating table in four of the five agreements in the residential sector of Bizkaia. The strike began in March 2016 and was on the front line until the negotiation of the last convention that was held until October 2017.

Arantza Arrien Goitiandia (Casera)

Arantza Arrien Goitiandia (Casera)

Born in Aulestia in 1963, a decade ago he moved to Ozaeta. He is a baserritarra, trained agricultural technical engineer and member of the Etxaldeko Emakumeak group, whose axis is food sovereignty. They intend to dress feminism with food sovereignty and, at the same time, to incorporate the feminist perspective into the movement rural.Ha was delegated from the EHNE trade union for years and currently works half a day in the Rural Development Association of the Llanada Alavesa.

Elena Vasconez Cevallos (Hotel Cleaner)

Born in Ecuador in 1980, he emigrated to Valencia in 2003, leaving his four-year-old daughter in charge of a  relative in his home country. There he worked in surveillance, field and cleaning, until he decided to move to the Basque Country in the hope of finding better living and working conditions. He currently serves as a cleaner at the Hotel Barceló Nervión in Bilbao, through the Constant subcontract. Demanding the improvement of their working conditions, they held 47 strike days between November 2018 and January 2019. There he premiered as union representative of ELA.

relative in his home country. There he worked in surveillance, field and cleaning, until he decided to move to the Basque Country in the hope of finding better living and working conditions. He currently serves as a cleaner at the Hotel Barceló Nervión in Bilbao, through the Constant subcontract. Demanding the improvement of their working conditions, they held 47 strike days between November 2018 and January 2019. There he premiered as union representative of ELA.

Economists love the charts that represent the behaviors of the markets, which are curves. I was struck by the analogy of author Cory Doctorow in the article “The future of Amazon coders is the present of Amazon warehouse workers” on the Pluralistic website. He researches the... [+]

Buñueleko (Nafarroa) kasuan, 34 urteko gizona makina batean harrapatuta geratu da. Arratzun (Bizkaia), aldiz, garabiak goi-tentsioko linea bat ukitu ostean hil da 61 urteko gizona.

Betsaide enpresan gertatu da, 08:00ak aldera. Urtea hasi denetik gutxienez bederatzi behargin hil dira.

2024ko laneko ezbeharren txostena aurkeztu dute LAB • ESK • STEILAS • EHNE-etxalde eta HIRU sindikatuek aurtengo otsailean. Emaitza larriak bildu dituzte: geroz eta behargin gehiago hiltzen dira haien lanpostuetan.

Jakina da lan ikuskariak falta ditugula geurean. Hala ere, azken egunotan datu argigarriak ematea lortu dute: lan ikuskaritzaren arabera, EAEko enpresen %64ak ez du ordutegien kontrolean legedia betetzen. Era berean, lehendakariordeak gaitzetsi du, absentismoaren eta oinarrizko... [+]

-(1).jpg)