"It's all an image, but people don't have time to see those images."

- He's never drawn a bird, although he's passionate about birds. He'd like to go through cities behind birds' feathers, looking for different colors, different stories. Being a painter makes it rare, especially when it comes to figurative works and black and white. Rara avis is free.

He does not know for sure whether he is to blame for the documentary The painter of Oier Aranzabal being published in black and white – the film reflects on the selection, the difficulties, the solitude of the creator from the experience of the musician Mikel Urdangarin. “He should say that… In fact, the documentary is rolled in color. Oier has already taken a few photos and has always told me that he was not able to edit them in color. The same as in the documentary, when he started editing my part, he couldn’t do it in color.” He also participated in the documentary Alain Urrutia (Bilbao, 1981), making a certain counterpoint to his friend Urdangarin. Urrutia is a wandering bird. He flew from Bilbao to London in 2014, and there he had his nest for three or four years. Last year he went to Berlin. Always in search of new challenges, new cities and birds, new lights and colors, even black and white. Study by Schönhauser Allen, small, white. A table filled with brushes, a corner of thought with slate and three walls coated with its walls. He received us at the end of spring, at the Casado Santapau gallery in Madrid, before the exhibition The Age of Anxiety.

The change from London to Berlin has not affected you: you're still black and white.

Well, there's a lot of black and white. What is that behind you, black? [Pointing out one of his works] No, a blue one, right? My jobs are colored. However, we don't have color memory. There are different white and different black: hot black and cold black; hot white and hot white. I use different whites and blacks and sometimes I also add them red and blue. There's and I use hues, but people don't perceive them.

Do the painter's eyes help distinguish these blacks and whites?

We have thousands of ways to call the trees in Euskera, depending on height and whether they bear fruit or not: tree, tree, bush, zuhaiztxo… and we, today, do not differentiate many of them. The farmers, the peasants, etc., yes. People who work in clothes know how to distinguish colors. I put hours and hours in charts. You learn to see with time.

Does the use of black and white, even if it is diverse, have a special symbolism for you or has it been a practical issue from the outset?

Practicality is something I've never been told, and the initial reason was that it was practical. I was very lazy to work, and a friend told me, if you want to be a painter, you have to paint every day. No matter what you want to do, you have to do it every day. There is no other choice, and I forced myself to paint. I started painting a portrait a day. My intention was to spend an entire year like this. That was in 2006, and I spent five or six hours doing each portrait. I went out into the street, with my pocket, taking pictures and then portraying what I had seen. Every day, I agreed. I made about 86, all black and white, and the reason was practical. Because it was easier.

Has it not even proposed for the time being to resort to more intense colours?

The color is shown in my grays, and in the last exhibition in Madrid it is much more evident than in the previous works. That doesn't mean I'm going to jump into more vivid colors. I'm not happy when I'm surrounded by vivid colors, I feel out of place. In our environment, in nature there's no vivid color either. And probably, yes, the time will come to paint a red sky, but at the moment I can't predict when. For now I intend to continue painting in gray and it will be shown if the color has to be shown. As the letter of Zea Mays states: “…coloring the black white with each beat”.

In the film The painter tells the difficulties he has to be a musician, the pressures of those around him, etc., because he often does not relate to a trade. When did you decide to be a painter and lived that pressure like Mikel Urdangarin?

I had by nature turned to science, but at the last moment I decided I wanted to learn art. My parents said to me, “Alain, you’re good at science, engineering comes out, you study architecture...” Well, in the end they accepted it, but they told me why I didn't study design inside Fine Arts, and so I did. I liked to put myself in front of the computer, to draw drawings… The third year of my career I went to Italy, through the Erasmus programme, to Milan. 18 September 2001. I knew nothing in Italian. There everything changed. A week after the twin tower. That day, I decided I would be a painter. They came to college and asked me. “What you do.” I answered: “Design.” The design is drawing for them, painting. So I got a professor of painting and drawing. I understood the mistake, but I decided to shut it down. So I decided I wanted to paint, and I realized I wasn't stressed out: with a beer I was painting, in class, with peace of mind. That's one more step to take the paint seriously, but it was that germ.

Do you consider yourself a painter, a painter?

This is an old controversy; you take it as a creator ... I have worked as a burial in Wisconsin, I have worked as a nougat or as a tabernacle; I have also been a magician, I have done sport, sometimes more serious than in others… I would not define myself as a painter, but I know I do nothing else… I don’t know if I will come anywhere with what I do, but at the moment I intend to do it. In Greek, the painter is called Zoegraphos. Zoe is life and Graphos is a writer; with that I identify myself more. I've been writing life with painting for a long time.

.jpg)

worked in Bilbao and London and currently lives in Berlin (photo: Gorka Erostarbe).

You first went from Bilbao to London, then to Berlin. Always looking for contrast?

A friend says we always have to do what we don't know how to do. And I try to paint what I don't know. Otherwise, we don't learn anything. A lot of people are comfortable with what they know how to do and it's OK, but I need to go and look for it. In Bilbao, I was very comfortable. I worked at the Kafe Antzokia, I painted, I won a lot, I saw as many concerts as I wanted… life was extraordinary, I needed nothing else. But I tended to look for discomfort. In addition, I am a great tongue lover; I arrived in Berlin a year ago. I started studying German and I won't say I speak, but I feel able to communicate in a very basic way. And I know from here I'm going to move somewhere else and learn another language. I know where I'll end up. Basque Country. Middle -- the road will tell you.

In the movie, there's a very powerful sequence. You and Urdangarin are in London, in the white giant noria. And you're talking about success, about being up or down. What is success for you?

It will be a topic, but what I want is to live peacefully. Paint, expose and earn enough to live. I don't need much. I wouldn't know how to describe it, but it can have something to do with quiet.

Is this not in contradiction with the point of discomfort?

Yes, but being uncomfortable doesn't mean you're not comfortable. That is what happens to sport. You make an effort, you feel uncomfortable, but then you feel at ease and calm. What I want is that calm that happens with sport. You can't control the reception of your work in people. What I want is for people to change the way I see my work, to change their time.

What do you mean by time change?

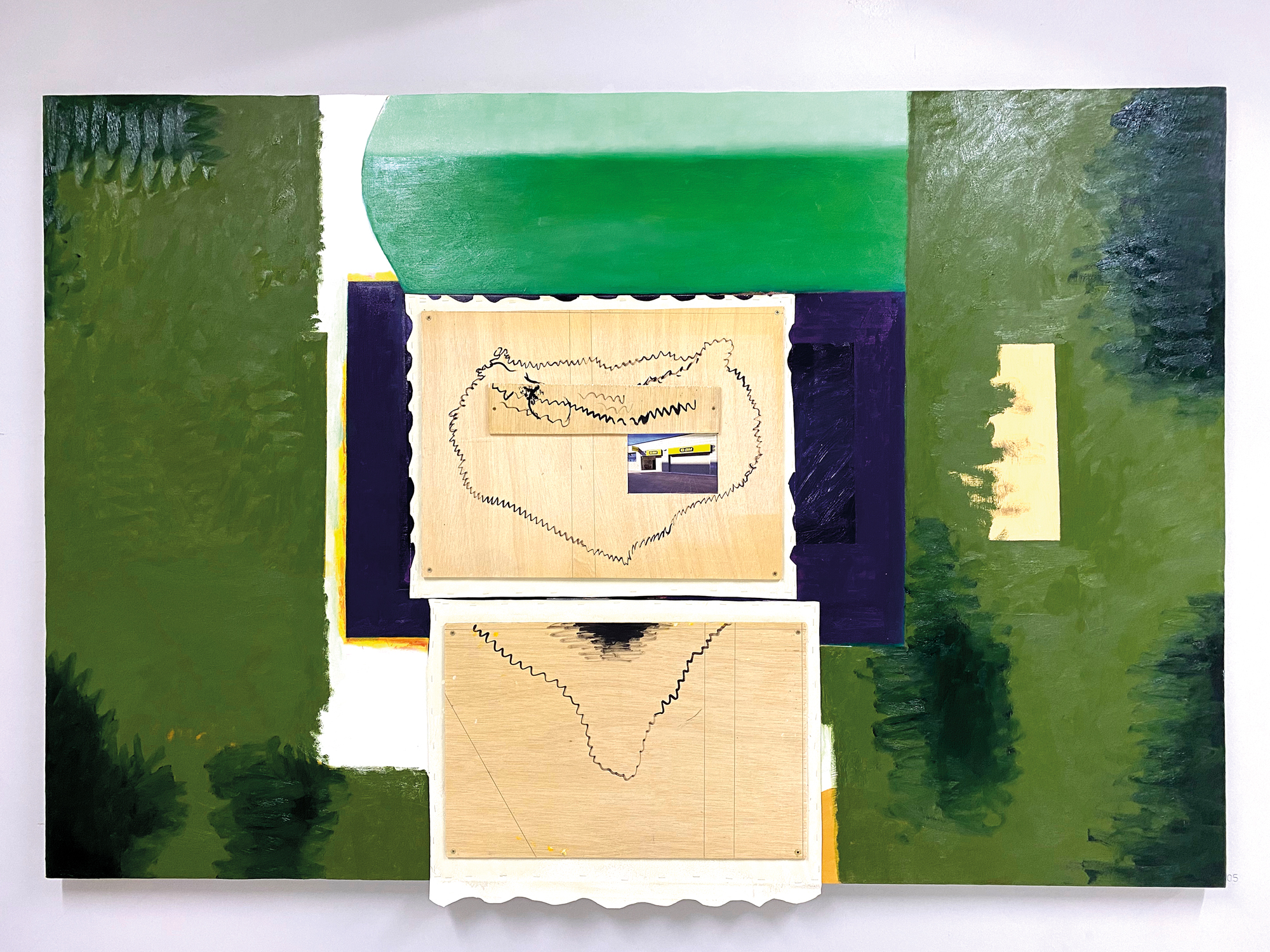

When people see my little squares, it takes a little longer. What I'm doing is people are analyzing and thinking about how they consume art. A few years ago, when I put the exhibition at the Guggenheim, I had a hallway to put works. In that hallway, I put a piece of four and a half meters high and eleven meters wide. Why did I do that? If I saw the distance or not, I would see it. I was just a Fine Arts student and had just finished my career. People went to the museum to see large exhibitions and works of known names. This was my opportunity to draw attention. To gain attention and time. I see it at the opening of the exhibitions: people see hardly any works. Talk, take some wine, but it doesn't take time to see the work. Instagram equally. Everything is picture, but people don't take time to see them. Against that, I made another exhibition with nine small paintings. A completely different strategy. You walk into a gallery and you have to zoom in to see those little paintings. The exhibition I made in Madrid was titled 20 minutes of abstract thought. I didn't want to write an explanatory text to see those paintings, I didn't want to condition your gaze.

"In the opening of the exhibitions, people barely see works. Talk, take some wine, but it doesn't take time to see the work"

Do you not like these expositional texts?

I don't like to give too narrow explanations; I can give clues, some keys, but open readings or encourage the viewer to explore more. Not limiting reading, the challenge is to extend it further.

Margolaria explains the relationship between the musician and loneliness. How do you have it?

Today we have difficulty concentrating. So I also put that title: we need 20 minutes to develop abstract thinking. I've often thought about that when I run. Loneliness is good at developing this abstract thought. In this same study, I spent hours and hours alone. I'm just leaving the studio. And I'm not lonely, I'm social. But painting has a lot of loneliness; the paintbrush, the curtain and yourself. You spend hours in front of a little painting. Productivity is ridiculous of art. Take the hours and the hours, but you may only find a job useful.

It's about giving time ...

I need a lot of time to paint the paintings, I take a lot of time. In June I had an exhibition in Madrid. I painted the pictures of that exhibition when I arrived in Berlin. I finished them last summer, and then I let them breathe, and the last hairstyle I did at Christmas. Many artists are changing things to the last moment. I cannot do that, and in the same way I try not to show the works done on the Internet in advance. The media and today's society are demanding speed, and I try to avoid it. A lot of people say: “I have seen that picture.” No, no, you've seen an image of that painting on the Internet, but not that picture.

Against anxiety, time?

Anxiety is what I perceive in our current life... and hence W. H. Use of the title of Auden’s poetry as the title of the last exhibition in Madrid: The Age of Anxiety. The anxiety that Auden wants to express in his poem is totally different from what I wanted to express in the exhibition. Also, the main axis is the social gap that remains after the Second World War. But in mine, what today is a great facility to read images or life. Speed. I ask the viewer for attention when it comes to understanding my work, time.

How does it affect you to be in Berlin as an artist, to be outside Euskal Herria?

It would be harder for me to be there right now, or how I could have made him be a painter while there. The painting is not in the mouthpiece in Euskal Herria. There, I probably wouldn't have a place. I have achieved respect, but I managed to do so when I started making exhibitions in Madrid. I wasn't in Madrid either, and I got respect when I went to London, and so ...

The painting isn't in the mouthpiece. Conceptual art or performance. How have you experienced that interdisciplinary tension?

Inside the painting I am also a little weird avis, as I work the figurative. That I will not manage to make the way by following its rules, well… Since the end of the 20th century there has been much talk about the death of painting. There have been many thinkers who have written about the death of painting and that is what many painters today complain that they do not find their place within the artistic system, what they say in self-defence. If you ask a sculptor, photographer, performer or any other artist, their concerns and concerns will be very similar and their defense will be done in a similar way.

And now, what?

I have projects in my hands, in Bogota, in Mexico City, in the Basque Country… I don’t like to set goals, because when you get there, what? It's about sticking to yourself. Think I have the following objective: I want to show it at the Guggenheim. Did I? Now what? It makes no sense to set such goals. It is not good that the objectives should become limits.

Have you ever painted birds?

No, I haven't drawn any birds. I've had a fixation for birds for a long time… When I went to live in London, I found a crow pen in the park, and in that pen I found the grays I was looking for until then in the painting. From that point on, I was clear that I would go to other cities to look for new feathers. This idea is the starting point of the documentary Luma Berriak bila by Itziar Koteron about my work.

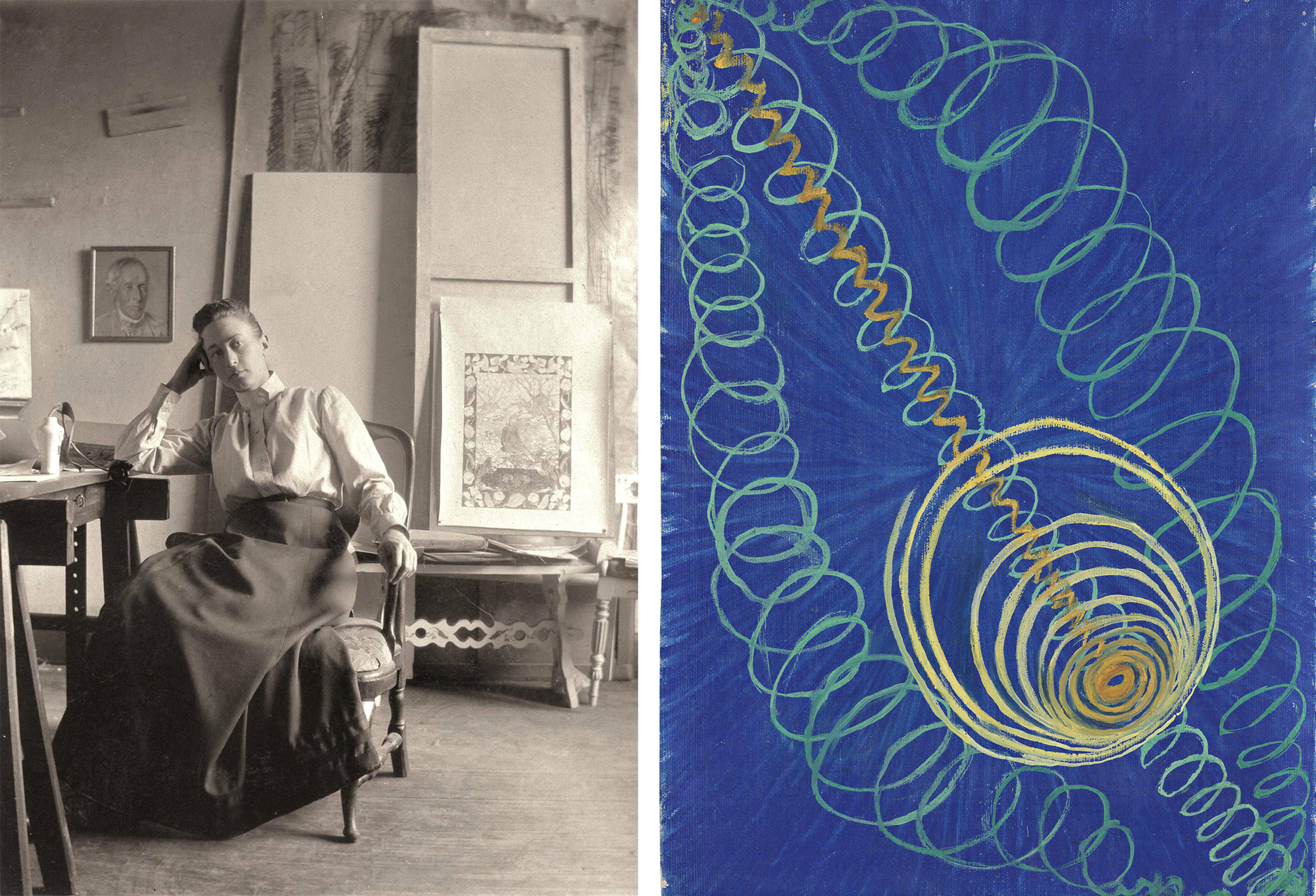

Bussum (Netherlands), 15 November 1891. Johanna Bonger (1862-1925) wrote in his journal: “For a year and a half I was the happiest woman on earth. It was a long and wonderful dream, the most beautiful one I could dream of. And then came this terrible suffering.” She wrote... [+]