Inclusion, or who

Inclusion is a subject that is on the lips of many. To the extent that we are far from being able to carry it out, both in education and in society, it is the utopia of a better way of living together. Given that in reality taking steps towards inclusion is a slow process, perhaps the literature can do a faster process. That is, it can simulate the process in a fast camera. Can literature be a place to imagine that utopia, to start drawing, to move forward? Is it already?

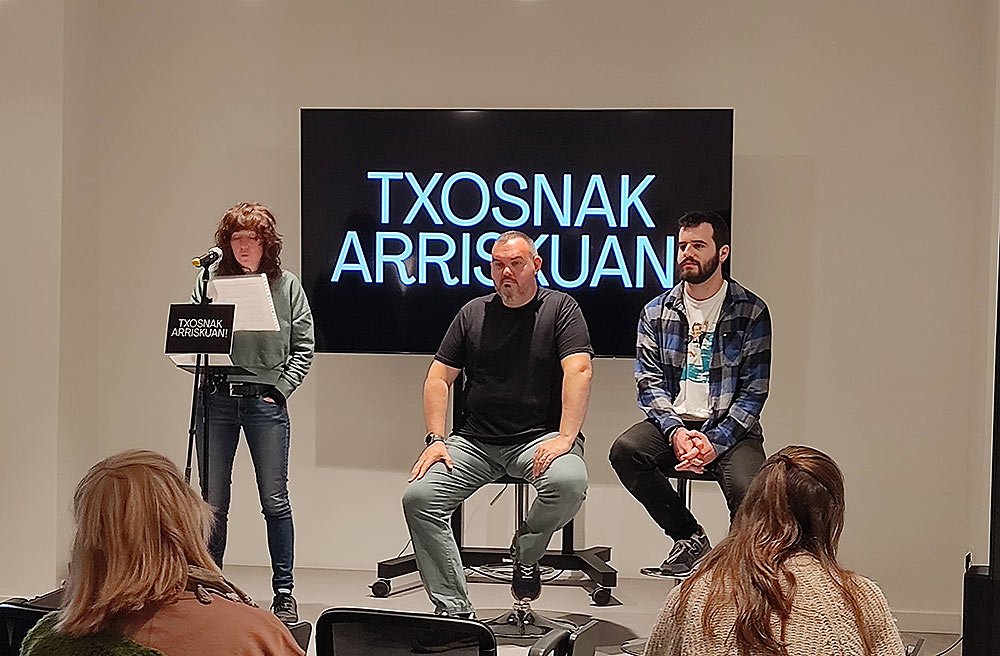

I approached an act with the intention of knowing where and how the children's and youth literature works. The inner chamber sounded for a few seconds, about a hundred people. In total, three men. The three in the front row. One of them was in a wheelchair.

At the beginning of the round table, it was found that one of the men was a participant. What I heard there was nothing new to me. Very general things were said. Among them, that everything published with good intent does not achieve its objective. In fact, it is not a question of bringing the politically correct subject to books as petachos or adornments, placing the black child or the mutilated child in the images of an illustrated album (inserting it).

The one who reads regularly is something he knows: the main (or unique) characteristic of a character. If it's a wheelchair or a headscarf, the character will inevitably be flat. This characteristic of this character (labeled, black, poor, without mother or father, transsexual, alien: x) will not like the reader that is within his identity. Readers (age and everything else is the same) cannot identify with flat characters. One of the functions of literature is to try to open windows into our inner lives and those of others. The story, if left on the surface, does not produce emotion, so it cannot create a real moment of understanding. But of course, inclusion, as in society, can only come to literature in the hands of diversity. Diversity in character types, stories and aesthetics.

In the final question turn, the man who was in a wheelchair also showed that he belonged to the project of one of the participants. I will open a parentheses in line with the above: What I have described (labeled) as a man who uses a wheelchair in a little, says on his website: “Berlin. Writer. Presenter. Author of the media. Ambassador. Inclusion Activist.” This more comprehensive list also refers to some aspects of his identity, which he has chosen to present publicly. It would still be a long way off to become the (complex) character of a fictional story! The third man, almost at the end, showed that he was deaf. When the translators translated their questions.

The clearest conclusion I got from going to this act is that no man came to listen, without being directly involved with the theme. If the man at the center of the norm is a white, heterosexual, non-paralytic middle-class man, if it is significant that none of those present in the center have attended the inclusion act. Or not?

Those who believe they are normal are the last ones who would stay to inquire if the margin gains strength by bringing the image to the end. The one in one of the corners also claims normality, but as long as we are not all normal, no one is normal.

BRN + Neighborhood and Sain Mountain + Odei + Monsieur le crepe and Muxker

What: The harvest party.

When: May 2nd.

In which: In the Bilborock Room.

---------------------------------------------------------

The seeds sown need water, light and time to germinate. Nature has... [+]