Alternative for young homeless migrants

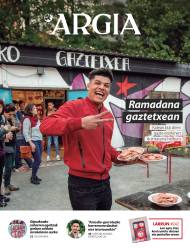

- On Intxaurrondo Street in Donostia-San Sebastian it is common to see young Arabs at lunch time. There, the friends of Caritas distribute snacks every day. As of May 6th, not for lunch, young people meet for dinner. And not in Caritas, but in the gaztetxe Letaman, located a few meters above. Thanks to the Modahara collective, these homeless Arab youths from Donostia-San Sebastian have had the opportunity to celebrate Ramadan according to their customs this year.

"I'm Ayoub, in the children's center of San Sebastian, after two months in the center, when I turned 18, I was thrown out in the street. Why is there no room to sleep for those over 18?” “Today, at night, with less than 0 degrees, an emergency shelter will open for all people living on the street. Open from 22:30 am to 7:30 pm. Isn’t the rest of the day cold?”

More than 150 young people are on the street in San Sebastian homeless: most sleep on the street, travel from one hostel to another or occupy empty houses, among other things

Several young Arabs have told their experiences through the gaztetxe Letaman’s public address. Self-managed space is transformed in the evenings from 6 May to 4 June – or until 5 June, as it depends on the moon. Members of the Gaztetxe and the Modahara group have prepared a grill fig tree so that young people who are fasting throughout the day have something to eat and, above all, to have solidarity.

Ramadan is a month-long fasting in the Arab countries. Although from the eyes of the Westerners it is linked to Islamism, so is the non-Muslim Arabs, who see it as the basis of their culture. Like Atheist celebrating Christmas, for example.

From sunbathing to hiding, you don't eat, drink, smoke or consume, or have sex, you have to be generous and honest, always according to the Qur'an. At dusk, they gather, pray, and break the fasting.

.jpg)

In gaztetxe Letaman twilight goes well. While some cook, several musicians and improvisers are setting the atmosphere in a good mood; a young man who, although he does not master the Spanish well, asks him “another”. Small football competitions are also organised, as well as other workshops: in recent months a hairdressing and laundry service is being carried out every Tuesday in the gaztetxe itself.

For the Arabs, Ramadana is an important ritual for community building. Families and friends come together and celebrate the ritual together every day. After dinner they go to the streets and the villages know another way of living. But there are those who, because of the circumstances, are far from the family or do not have it. Or as in Donostia, no house where they don't come together.

"Protest" of those on the street

“In May of last year we organized a conference on the impact of migration in the city,” says Leire San Martín, who works as an educator with migrant youths, it was clear that we had to go beyond the work of educator, that we had to overcome the institutional limits.”

The result of this process is the Modahara collective, which in the Dariya language means “protest”, which wants to go beyond mere assistance with homeless Arab youths. They have been in charge of organising this year’s Ramadan Solidarity, always in cooperation with the young.

For the Arabs, Ramadana is an important ritual for community building. But there are, as in Donostia, those who have not met without a home.

Although the exact number cannot be known, in San Sebastian there are more than 150 homeless youth: most sleep on the street, travel from one hostel to another or occupy empty houses, among others. It's the other side of the Donostia of the postcards, the one that nobody knows, the one that doesn't want to know.

The members of Modaha underline that behind the joy that is being experienced these days in Letaman “it is a very difficult situation”. Educator Ana Revuelta is also part of it: “If you know a young man who has a lot of strength, who is absolutely optimistic, you think “what the fall is like.” Because you know it's going to fall down, down, down, especially from the point of view of mental health." Ander Mujika, who works as a volunteer, is also present. Know the situation of people living on the street well: “They spend nine months on the street before entering a shelter. They arrive well in San Sebastian, but when they enter the hostel they all have a collection of pills, especially to sleep.”

.jpg)

Revuelta believes that it has to do with the institutional logic: “They go through a lot of places: the place where they eat breakfast, where they eat, where they do theater, the educators… everyone builds their own relationships and it’s not easy.” Each institution fulfills its role, but they point out that there is a lack of vision that places the person in the center: the hairdressing service would be the simplest example. Until they were told, they were not offered the service. “We offer services from our point of view – and from each institution – but so far no one has thought of everything,” he says.

Letaman respirator

Volunteers and young people are in charge every day of shopping in the city center. Young people are in charge of cooking. He comes to Abdelal every day, but today we've been told he's got "work."

St. Martin makes it clear: “Working in a horizontal space with young migrants as educators and militants marks me a lot: I’m living a process that excites me completely.”

Among the members of the gaztetxe who are not accustomed to being with the homeless and the neighbors who go to dinner, the wonder is the same: “I feel that to understand this I have had to remove a part of my brain.” “It’s beautiful for me to live this together and get infected with these feelings,” adds another. It has given me a new way to get closer, seeing a new path to relate to the next one.”

It is creating a very nice relationship and in these dinners you can find photos that are not easy to find in Donostia. With the dances, songs and exchanges of experiences of young people, really exciting situations are happening, as we've been told.

But without going any further, in the bar next door, several neighbors look at the young people with suspicion. And then you realize that even though the work of these volunteers is impressive, there's still a lot to do. Because racism is very alive in the institutions and in the citizens of the area, also in oneself. Modahara and Letaman propose a model for taking steps, for everyone who wants to make the way.

"We're so grateful."

Azedine Bahloul has come from Morocco. He has been living on the street for six months in Donostia, and every day he goes to Gaztetxe Letaman of Intxaurrondo at Ramadan dinners. He didn't want to show his face in the photos.

What is your current situation?

I am 18 years old and have been living in San Sebastian for six months. I've been in a children's center in Melilla for four years, and when a friend came out, he told me to come to San Sebastian, who would help us here. I have to be on the street for nine months, and then I hope to go to a hostel.

What is Ramadana for you?

It allows us to come together with God to feel closer. It is very important to us. On the other hand, cleaning is important for the body and helps to keep it more sana.Para washing the body and soul. It's also a good way to connect with the family and with our community.

Does it relate to religion?

Some pray and others don't, we don't just Muslims. Some of us go to the mosque at the end of the fasting. But in any case, everyone does Ramadan.

How do you live in San Sebastian?

Harder, by the distance, but we've found a beautiful place. For me, the first and last days are the worst, I am very hungry in the first and I really want to eat in the last.

What is your relationship with the young person?

We are very grateful to the people of Gaztetxe and the rest of the volunteers, they are being very generous and give us the opportunity to meet each other. Our situation is not always easy, but they give us strength to move forward.