They killed the daughter of the Sun

- The lack of justice feeds the memory. The more unjust the wounds are, the more we remember and carry in our hearts those who suffered them. With Gladys Del Aparl something similar happens, since from the first minute it was detected that the citizens were facing an unjust death, if there is a fair death. The reaction that led to the killing of the environmental activist in Tudela by the sub-rifle of a civil guard on 3 June 1979 during a pacifist session is hardly forgotten: the general strike paralysed the Basque Country until the collapse of the anti-nuclear pot. For this biography we have talked with the friends who met him, we have analyzed documents, newspaper archives, newsletters, records, messages... and we have brought to light unknown data. In these forty years the shadow of impunity has prevailed at dawn, as the agent who killed Gladys has not paid for what he had done, but for the medals. The black tint of the official version has stained the story. But ... No! That was not a disgraceful accident, but the consequence of a calculated repression which during those years filled our shores with smoke and lead jets. And Gladys was not by chance on that bridge of the Ebro, but had been driven there by his commitment and temperament.

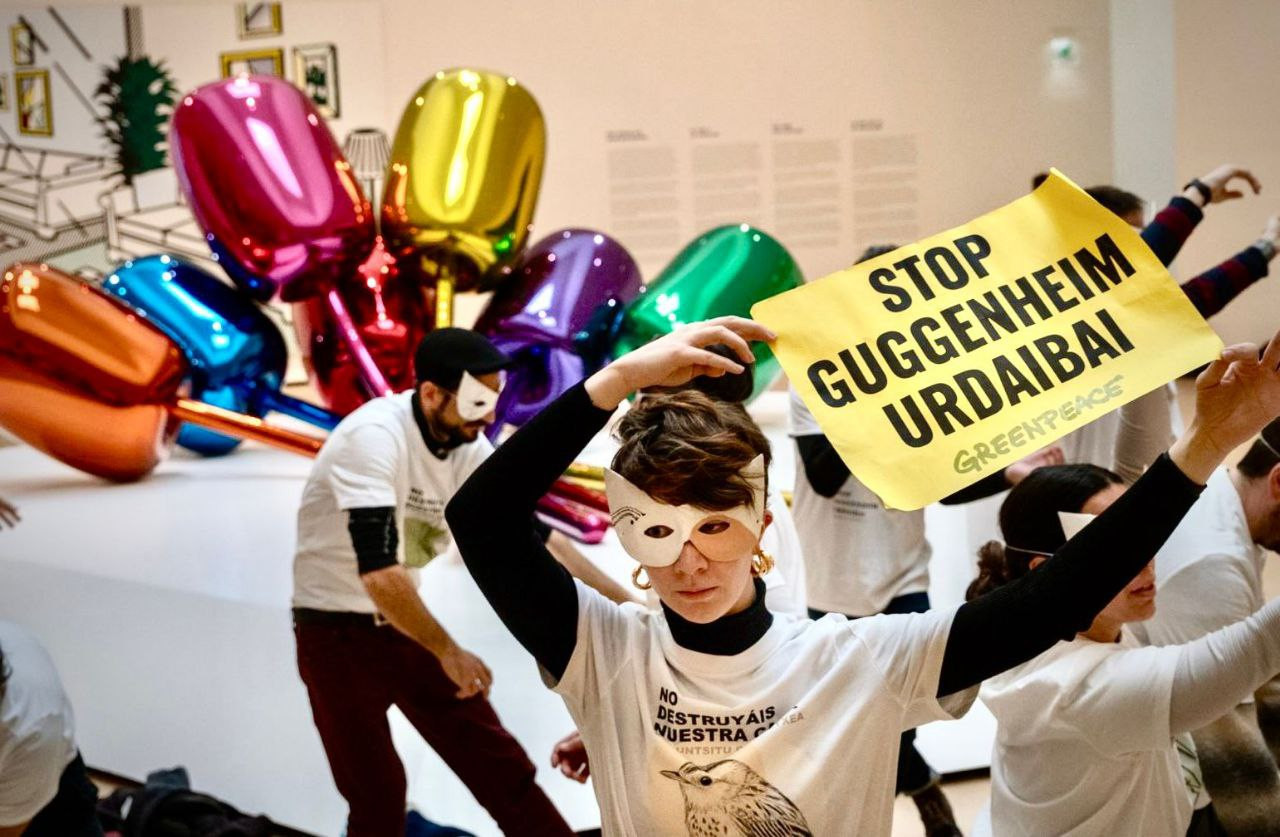

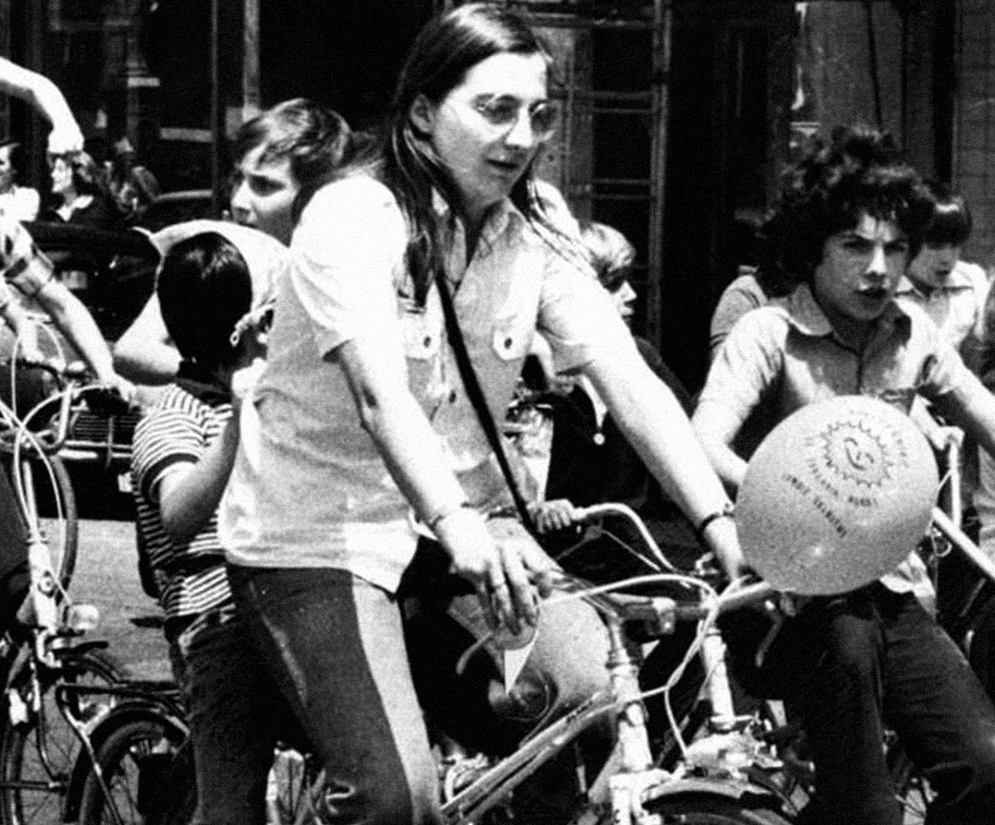

A smile came out of his cheeks. Behind his round glasses he had a look of cordiality. He wears his hair long and loose, stroked by the wind as he pedalled. Balloons in the handlebar, a drawn antinuclear sun. And behind the chair a child helps him. Gladys Del Sat did not miss the opportunity to participate this Saturday in the bicycle march for the youngest by the streets of San Sebastian with his Orbea Cometa as a prelude to the great mobilization that was going to take place in Tudela. The cameras caught up with it, and that's how the Egin newspaper got to its surface the next day. The day he was killed.

The International Day of Action against Nuclear Energy was celebrated around the world on 3 June 1979. In the western countries of Europe, Japan and the United States, great protests and demonstrations took place, as the serious accident that took place two months earlier in Harrisburg revealed the lies of nuclear power stations: there was no safe power station. In Euskal Herria, Tudela was the main nucleus of the mobilizations. Just seven kilometers away, the Franco's energy plan contemplated the construction of a nuclear power plant in the area of Soto de Vergara, in Arguedas.

.jpg)

The organizers prepared the program all day, in a festive and festive atmosphere. But as for police controls and provocations, they soon realized it wasn't going to be a quiet day. Not very much. Early in the afternoon, when the crowd was returning to the buses, a civil guard killed Gladys del Estal, across the bridge across the Ebro, with a head shot. He was 23 years old. From there, we already know the general strikes the following day, the police repression in the months of Donostia, the trap in the sewers to exculpt the murderer…

Since then, the death of the Donostian entrepreneur has become a symbol of the environmental movement in the Basque Country. Every year they have remembered it in the Gladys-Enea Park of Egia or in the march against the shooting polygon of the Bardenas, and we have seen his smile along with a lot of stickers and afixas next to an orange sun. But who was Gladys Del Estal?

From Venezuela to Egia: three committed generations

You wanted to defend a greener

people so that relationships

with the sun would sing out

of necessity ...

This is what a poem he wrote after his death says.

...from

the plant

the fruit of the seed

grows from the flower and restarts.

Gladys Del Estal Ferreño was born in Venezuela in 1956. His parents exiled themselves to the country after the 1936 war.

Enrique Del Estal Añorga was born and died attached to the bicycle. In the prewar he ran in Barcelona, and when the fascists took over Gipuzkoa, he had to flee from San Sebastian on two wheels. He voluntarily joined the Basque Army and militated in the front line socialist battalion Meabe, from Legutiano to Cantabria. Then concentration camps and labor slavery. Prisoner of Father Montjuïc, shot the older brother... So he went into exile. It's curious, another brother fought on the opposite side. Tragedy of war.

.jpg)

Henry would take the monkey out of the garage every time he could. After his daughter's, we would continue to see the bike at the front of the marches. The painting and radios were destroyed in 1989, when the tree of a revolt was killed.

Eugeni Ferreño Rodríguez, the mother of Gladys, also ended in Caracas after the war. Affiliated with the union of the Clothing Industry of Gipuzkoa, Red Euzkadi stood up for supporting the Communist newspaper and its name is on the lists of evacuated people from Euskal Herria. Gladys' father, grandfather, was shot and then stripped of the bar.

The passion for the commitment of our ecologist was not born from scratch, but was fed by a string of several generations.

The .jpg) Del Estal-Ferreño family decided to return to Euskal Herria in 1960 with their four-year-old daughter. They were installed in the Egia of San Sebastian, at the beginning of Aldakonea Street, but were quickly moved to the fourteenth floor of the Atotxa Tower. That was where Gladys first hung the antinuclear banderola out of the window of his coarto, so that it could be seen in the legendary matches of the Real.

Del Estal-Ferreño family decided to return to Euskal Herria in 1960 with their four-year-old daughter. They were installed in the Egia of San Sebastian, at the beginning of Aldakonea Street, but were quickly moved to the fourteenth floor of the Atotxa Tower. That was where Gladys first hung the antinuclear banderola out of the window of his coarto, so that it could be seen in the legendary matches of the Real.

But we have hardly any news of his childhood, only that I walk through the school Presentation of Mary: “It’s amazing, when we started asking ourselves, we realized that the people of San Sebastian didn’t know him in childhood,” says Sabino Ormazabal, who worked with Gladys in the popular movement of Egia. It is also late. His brother Paul has stood aside and has never wanted to talk about his sister. “When the parents died, we lost that information.”

Member of the first environmental group

A smart, “hyperactive” person liked to learn. In this way it became popular with the friends of the university. When the computer race ended, in which one of the classrooms at the faculty will be named and an exhibition has been organized, the first course in Chemistry began. But he had the idea of biology, because everything related to nature was interesting to him, and he started working as a payment programmer at a small company. In the house shelf, books and reports on pollution or nuclear are overflowing in the black and white photo: “Gladys was self-taught, read a lot and was very aware of the society we had,” explains Ormazabal. She also started giving talks when she started working in the coordinator.”

The ecologist's endeavor was not born out of nowhere, but was fed by a multi-generational navel.

Here and there, nature lovers were organized in that coordinator. Two people used to give lectures, one of them Gladys, as part of Egia. In this neighborhood, an ecologist group of the former was created around 1976.

The writer Pello Lizarralde lived from within this group: “My colleague then and I were very concerned about a very new word for us: ecology. We didn't know where it came from, but we knew what it meant. There were serious problems in Euskal Herria, there was nothing but seeing what had happened to industrialization or how many pines were on the shores. We didn't know where to go, and suddenly we read in Alfalfa magazine in Madrid that they had created a group in Egia. I met Gladys there.”

In the ad, they only asked for ecological publications to sell them in the neighborhood. But that small step was the beginning of a fruitful route. Throughout Gipuzkoa there were no similar groups – except for some movements of the Urola and Goierri environment – and “as was so little, we met with everyone”. Gradually, these small groups were very effective. Lizarralde recalls that with the theater group Orain performed over 60 functions in the villages, “we did street theater, we knew it wasn’t very refined, it was like doing an action.” A bit of people separated the antinuclear wave from neighborhood to neighborhood and village to village.

.jpg)

At the beginning, moreover, this movement was not united with any party, the politicians were far away: “The people who were there had libertarian concerns, taken in the broadest sense, rather than patriots,” says Lizarralde. I think it wouldn't happen today, because parties always want to bring leadership to their side, but then there wasn't yet. That's why it spread so much. That terrible demonstration against Lemoiz, I remember it as a wonderful, sunny, joyful day... And we said to each other, "When will these [ETA] come in?" They were offside, because the political movement had no such concern."

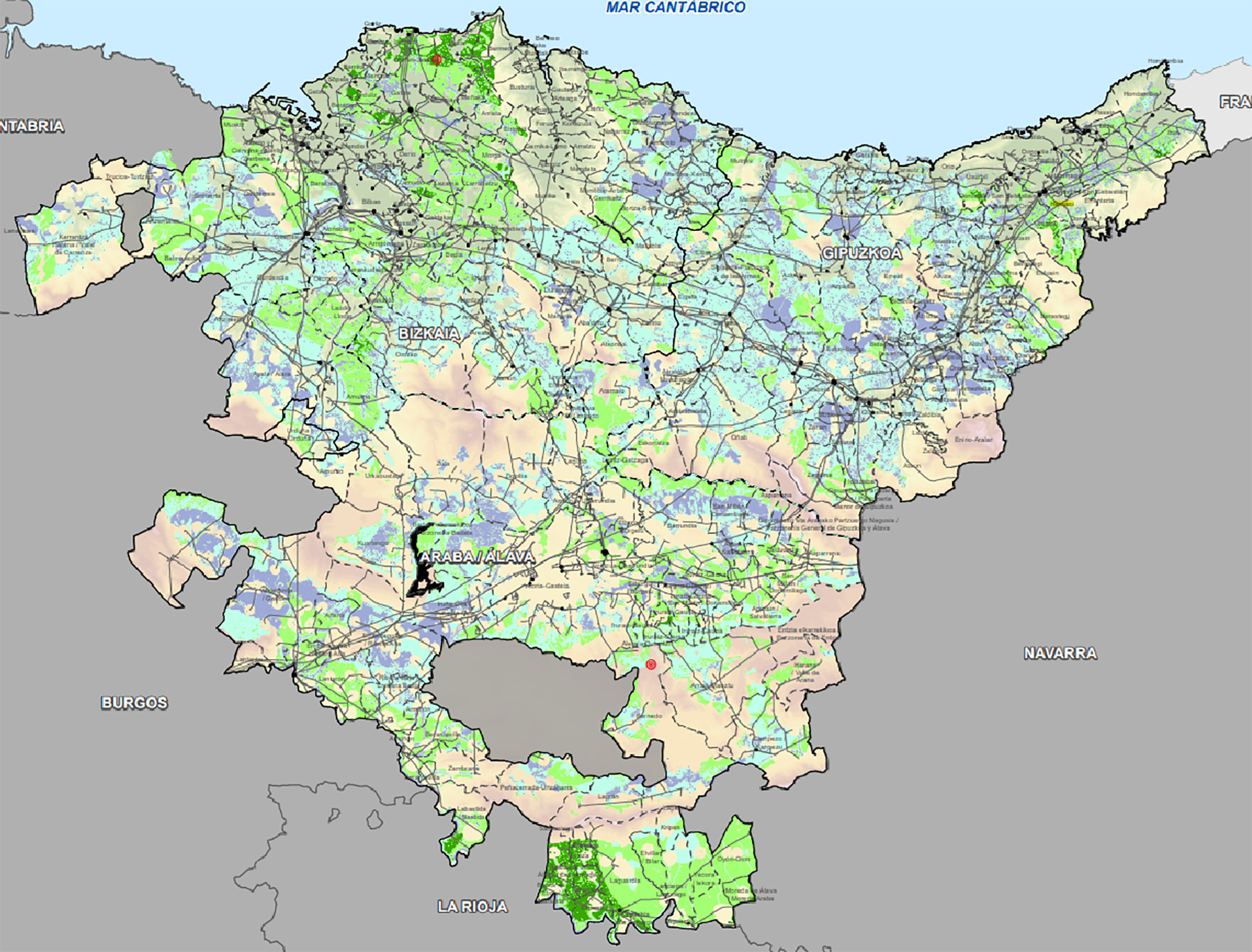

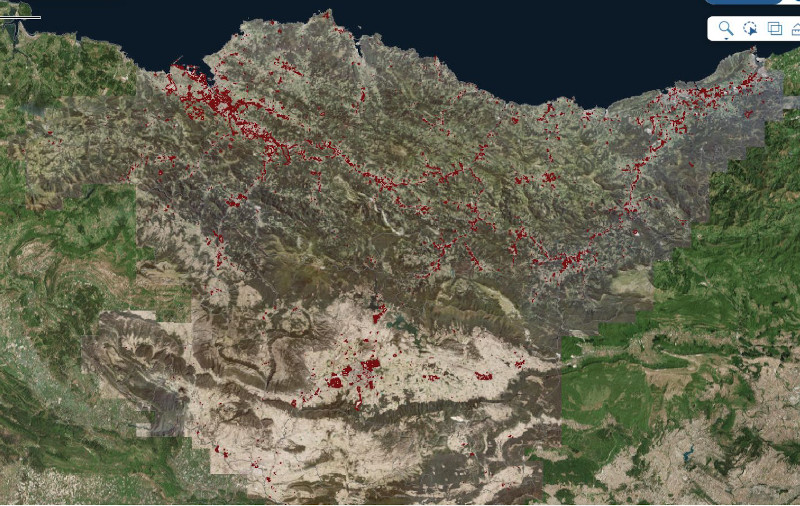

In 1964, the Franco regime passed the law to support Spanish nuclearization and the prolonged shadow of Iberduero quickly spread along the Basque coast: The company planned to install a nuclear power of 25,000 megawatts in the municipalities of Lemoiz, Tudela, Ispaster and Deba. The last three projects were stopped, among other reasons because the citizens quickly realized the practices of the electric company. On the contrary, the construction of Lemoiz had already begun. Thus the Pro-Costa No Nuclear Basque Commission was set up in May 1976, with the help of associations of families from different peoples.

"When traditional roads run out, the imagination of the people destroys the knot and opens a new path of struggle:

civil disobedience (not even the anti-nuclear magazine).

That sunny and joyful day reminiscent of Lizarralde was 14 July 1977 and 200,000 people gathered in Bilbao. Previously, ETA had placed three explosive devices in the dining room of the works of Basordá, and a few months later a member of ETA was seriously injured in a shooting between a command and the civilian guards who attempted to access the plant, in which David Peña passed away. In the following years there were more attacks, more kidnappings and more deaths. The location of the nuclear power stations at the centre of the armed conflict reinforced political opposition. In April 1979, the Basque General Council, the pioneering body of the current Basque Government, agreed to promote a consultation on the power plant, which, in the opinion of the antinuclear, was “undetermined, insufficient and inadequate” and which sought citizen demobilization.

In the meantime, the dockers initiated a general boycott so as not to land the material containing the reactor at the plant. Neither the magazine nor the magazine had a clear message: “When traditional roads run out, the imagination of the people destroys the knot and takes a new path of struggle: civil disobedience.”

When the Harrisburg nuclear accident took place in Penssylvania (EE.UU. ), which was supposedly “impossible”, caused much hunger for information and it was becoming more and more difficult to swallow the atomic project. Professor José Allende Landa wrote a letter from Caracas to a comrade of the anti-nuclear movement: “Iberduero, S.A. is a paper tiger. He has no arguments, and the reasons he uses are children's and stupid, who flee from Lemoiz's reality. These clumsy groups will always be won in confrontation. We are convinced of the arguments and that is our main weapon.”

A dangerous barricade in the Ribera

If he wanted something, he resisted getting it. I think that was one of the causes of his death.” In Tudela, when the police broke the festival, some decided to sit on the Ebro Bridge as a sign of peaceful protest at the disaster. Among them was Gladys. That is why Rafa Alday says that this way of being also influenced his death: “I didn’t agree and I had to do something.”

Alday met Gladys Del Estal in different movements of Egia. Among others, they taught at Maria Reina School to adults who wanted to get a high school graduate. He thought he was a serious and militant person. Many others who met the Donostian ecologist have also told us the same thing: it was rigorous in the conversation and in the ideas, firm, which led to the discussion to the end, but at the same time simple and smiling.

Alday met Gladys Del Estal in different movements of Egia. Among others, they taught at Maria Reina School to adults who wanted to get a high school graduate. He thought he was a serious and militant person. Many others who met the Donostian ecologist have also told us the same thing: it was rigorous in the conversation and in the ideas, firm, which led to the discussion to the end, but at the same time simple and smiling.

“I’ll speak

to you

in Basque Gladys, I heard

you killed...

But for those

But for those

of us who

have known

you,

you're alive.

You’ll always be alive.”

The bus that departed from Egia to Tudela on June 3, 1979 was organized by Gladys, a member of the district’s urban planning and environmental committee, responsible for a children’s environmentalist group. But his site became empty.

The festival was not organized by chance in Tudela. It was also intended to make visible the military risk of nuclear technology, and the bombings of the Bardenas were there: “At that time the six mayors of the area published a document against the project of Arguedas and the polygon of the Bardenas,” says Ormazabal who worked in the organization; they also began collecting signatures, with Mario Gabiria as the protagonist. This is how we intend to do something between ADMAR (Association for the Defense of the Environment of the Bank) and the antinuclear committees of the Basque Country. The poster read as follows: Absence of nuclear power stations. Out yankis of the Bardenas.”

.jpg)

If you start exploring in the internal file of the Pro-Costa No Basque Nuclear Commission, you will find a list of “interesting contacts” pointed with a coarse marker on the lid of a cardboard folder. There are the names and telephones of many of those engaged in nuclear research at the time: José Allende, the radiophysicist Pere Carbonell and also the Navarre sociologist and ecologist Mario Gabiria.

That joke of the stories of Asterix and Obelix summarizes the environmental policy of Navarre at that time: we will cut the forest and build a natural park. There were many conflicts in the old kingdom (pollution of the Arga River, second phase of the highway, ski slopes of Belagua…). Gabiria, he founded the ADMAR association when he returned from California in 1975. He brought to the shore of the Ebro what he learned from the anti-nuclear movement with Milagros Rubio and others. Thus the sokatira was launched against the construction of the Arguedas power plant, as well as the fight against an arms factory, the Ablitas aerodrome and the shooting range.

“What were the ecologists to Tudela? Protest against the power plant and the shooting field. In this symbolic struggle between military and military opponents, there was a real, non-symbolic struggle” (Karlos Irujo).

Putting the barricade of environmentalism and anti-militarism on the Bank, to what extent did that movement turn into dangerous for the State? The Wikileaks cables also show worldwide concern on the ground about the shooting of the United States. On the other hand, the issue of territoriality was at its height, and on the same day of the “national” festival of Tudela a plenary session was held in Vitoria-Gasteiz to discuss the draft Gernika Statute.

.jpg) The cocktail contained too many ingredients to please the police. And the police already had a history of this kind of stress, as was shown in the week of the amnesty or in the Sanfermines of 78. Controls were installed in the Tudela area and buses were forced to make a return of 50 kilometres to deviate from the Ebro. “The txofers were given a map with everything!” says Ormazabal. In their opinion, they prepared him militarily, because he was in a “sensitive” place. Karlos Irujo is of the same opinion: “What were the ecologists to Tudela? Protest against the power plant and the shooting field. In this symbolic struggle between military and military opponents, there was a real struggle, not a symbolic one.”

The cocktail contained too many ingredients to please the police. And the police already had a history of this kind of stress, as was shown in the week of the amnesty or in the Sanfermines of 78. Controls were installed in the Tudela area and buses were forced to make a return of 50 kilometres to deviate from the Ebro. “The txofers were given a map with everything!” says Ormazabal. In their opinion, they prepared him militarily, because he was in a “sensitive” place. Karlos Irujo is of the same opinion: “What were the ecologists to Tudela? Protest against the power plant and the shooting field. In this symbolic struggle between military and military opponents, there was a real struggle, not a symbolic one.”

Irujo is a member of the Lera Research Center of the UPNA and for the Government of Navarra has prepared an anthropological report on the memory of Gladys del Estal, with Txuri Ollo and other members of the Research Center. As we have been told, Gladys's death in a quiet action had not been successful: “People were sick of those people, too many people were dying because they were alone in the street,” says Ollo.

“When I heard the shot, I started running.”

Despite all the .jpg) administrative authorisations, including at the request of the representatives of the PSOE in Tudela, the planned actions were delayed for two hours that day due to the obstacles to controls. Still, according to the chronicles of the hour, between 6,000 and 10,000 people gathered at the Paseo del Prado in Madrid. Talks, snacks and jotas. The suffocating summer day developed in a good mood, until, after eating, a police bus and several service vehicles arrived at the festive enclosure at the gallop. The storm soon broke out: the first incidents, a detainee, the protest of the people, the pelotazos, the fear – “we were in a camp!” In vain the councillors and conveners tried to negotiate, the celebration was suspended, as well as the march to the shooting range scheduled for the afternoon.

administrative authorisations, including at the request of the representatives of the PSOE in Tudela, the planned actions were delayed for two hours that day due to the obstacles to controls. Still, according to the chronicles of the hour, between 6,000 and 10,000 people gathered at the Paseo del Prado in Madrid. Talks, snacks and jotas. The suffocating summer day developed in a good mood, until, after eating, a police bus and several service vehicles arrived at the festive enclosure at the gallop. The storm soon broke out: the first incidents, a detainee, the protest of the people, the pelotazos, the fear – “we were in a camp!” In vain the councillors and conveners tried to negotiate, the celebration was suspended, as well as the march to the shooting range scheduled for the afternoon.

But the police had drawn the military trap well. In order to reach the centre of Tudela, the underpass of the railway was closed and headed towards the Ebro Bridge to the population, families and children running. On the bridge the traffic was cut and around a truck a grupid had sat, chatting and merging. On the other side of the river, the civil guards of the road surveillance patrols began to hit without speaking; one of the first to straighten the hair gave a stab of blame to the woman on the ribs and shot her in the head.

“I started running when I heard the shot, to know how many meters I put fear in my body. I came back knowing that the wounded man was Gladys, I had to know where they were.” When Alday returned to the bridge he had already taken Gladys to the outpatient clinic, but the agents had grabbed him on the ground for twenty minutes without allowing anyone to approach. A few years later, Enrique Del Pope could not hide his rage from the press: "The doctors told me he might have been saved if they had taken him faster. That’s why I can safely say it was a murder.”

“While we were there, one of the girls realized that in the streets of Tudela no death was yet known, before the agents went down the window and yelled: We've been killed by Gladys! Gladys have been

killed!” (Rafa Alday)

Along with two Gladys friends, Alday managed to take them in a police car to the health center. “While we were there, one of the girls realized that in the streets of Tudela no death was yet known, before the agents went down the window and yelled:

We've been killed by Gladys! They've killed us Gladys!"

The cry sounded straight away. Within a few hours, the Tudela Corporation unanimously approved in the assembly a communiqué in which, inter alia, police chiefs are decreed and resignations are called for, and a general strike is called, backed by dozens of recently democratically constituted municipalities. The following day there were mass arrests in Navarre and two days later throughout the Basque Country. Machines in kietos factories, thousands of people in the street, cars and offices of Iberduero burning. In the Rochapea de Pamplona the security forces had to use snow-blasting machines to dismantle the giant barricades, as can be read in the Egin monograph.

Meanwhile, on 3 June, they were awaiting Gladys’ corpse at Donostia-San Sebastián. “They first took him to the reservoir of the Tudela cemetery,” says Sabino. I saw it. He had all the bloody clothes, and some municipal officials brought his daughter’s clothes.” There were Karlos Trenor, Fito Rodríguez and the three, along with other neighbors, until Gladys' parents arrived.

A multitude of truths never seen met in the burials. The outrage was so great that even a paisano agent was beaten. On the way to the graveyard, the police charges again. “I remember it as something special, I can count almost every minute. They were terribly insensitive to that attack. I was not beaten by chance, because I hid in an empty house, but the police entered the houses,” says Lizarralde even with a shiver.

There are photographs of then for history: in the coffin they buried the daughter of the sun with an ecologist-orange symbol. “That’s where the person ends and the symbol starts,” Irujo explains.

Official version: “cooperated” to commit suicide

Gladys Del Estal’s image has been linked to environmentalism, but also to impunity, as the civil guard who killed her received a ridiculous sentence – 18 months in prison, although it is not certain that she did – and was then decorated twice (see page 12).

The  version of what happened by Tudela's command is funny: a demonstrator wanted to take off the metralleta and, losing his balance in the fight, shot straight at Gladys' head. The judge charges the murderer "a crime of reckless recklessness resulting in death", which has already been arrested. In addition, Gladys was to blame. We have read this in the files kept in Pamplona, in the reply of the Ministry of the Interior to a judgment appeal: He says that Gladys was involved in the disturbances, along with the other demonstrator, and that he was “cooperated” for death, “to the production of the harmful event.”

version of what happened by Tudela's command is funny: a demonstrator wanted to take off the metralleta and, losing his balance in the fight, shot straight at Gladys' head. The judge charges the murderer "a crime of reckless recklessness resulting in death", which has already been arrested. In addition, Gladys was to blame. We have read this in the files kept in Pamplona, in the reply of the Ministry of the Interior to a judgment appeal: He says that Gladys was involved in the disturbances, along with the other demonstrator, and that he was “cooperated” for death, “to the production of the harmful event.”

What was about an anti-militaristic and peaceful celebration was presented as a stumbling block for dangerous activists. Minister Arias Salgado insisted on this idea to justify the operation, stating that some groups went to Tudela with the aim of “distorting the event” and that “terrorism was exalted”. Ormazabal still tears his voice: “In Black and White magazine they wrote that controls were put in place to “prevent the introduction of commands”... today you realize how far they were.”

To dismantle this version, the friends of San Sebastian made a popular report in which several of the respondents confirmed that the agent shot in front of Gladys. Alday doesn't know whether or not he intentionally did it because he was behind his back, but he has one thing clear: "In the official version it is said that they wanted to take the weapon away from the Civil Guard and the Civil Guard. That's a lie, a lie. I can assure you.”

Researchers at the UPNA have explained that although there were many people in the area, it is not easy to pinpoint exactly what happened: “You hear a shot but you don’t see anything, they killed him in that confused environment,” says Ollo. The Navarre Parliament also immediately opened a committee of inquiry, although the results were limited. We have had access to these minutes of Parliament and on our own we have seen the lack of detail of the testimonies: one closed his eyes, the other with the truck up to ... In the trial they behaved with these small nuances to impose only a slight punishment to the one that killed Gladys.

Report of injustice

Although forty years have passed, some maintain the civil guard version that that death was an “accident” – this has been done by the councillors of UPN and PP of Tudela at the municipal plenary held on January 30, 2019. Attention is drawn to the attitude of the socialists, the forcefulness they showed in denouncing the death, which has become an unconstitutional day for them. The official and institutional memory has “a character of truth”, explained to us from Lera Ikergunea. “They will never admit that it has been a state,” says Irujo, “this kind of death is always the result of personal behaviour or accidents.”

There are not few who think that Euskal Herria was turned into a laboratory of experiences in those bloody years of the Transition. Behind the policy of public order was a whole chain of command, from the Lieutenants to Rodolfo Martín Villa or Antonio Ibáñez Freire. The latter, the Falangist pro Nazi military, was Minister of the Interior of Spain when it occurred in the town of Tudela.

“But a sad Sunday was killed by the

civil guards in Tudela...

“We’ve found it written in

the

book of

poems …

They’re still walking through the

vignettes of our eyes

hidden behind those that allow him to kill gunmen

to the neck.”

“Injustice ignites memorialist movements,” the researchers say. But how do we remember Gladys? They distinguish the memory of family members from that of associations: the former remember the same person, the latter their activism and commitment. In addition, memory and discourse have been adapting to new times and new demands.

A special tribute is being prepared for this year through the Gladys gogoan initiative. On 1 June, events will be held in Pamplona/Iruña, Tudela and Donostia-San Sebastián. Before the tribute Eguzki organizes each year, a bicycle tour has also been organized to remember the one that took place in 1979 on the occasion of the International Day of the Sun. The images that are recorded on that day will serve for the documentary that is being produced about Gladys Del Tapa. The screenplay of the film was made by Sabino Ormazabal and is directed by Bertha Gaztelumendi, who will be presented in November at the Zinebi International Film Festival.

They will combine the smiles from before with those from now, as the past and the present are not so far away. Alday says that the demands of that time are almost equal to those of today: against the power of the military and the energy companies, for freedom of expression… “It happens that if you take a sit-in today you may end up in jail; before we received blows, now punishments. They want us to remove the instruments of expression, but we need to show our disagreement.”

So did Gladys Del Sat. And that's why we needed it alive.

[*Photos: Archives Argia, Fototeca Kutxa, Focus]

AEBetako Estatu Departamentuari Madrildik bidalitako mezuen bidez jakin dezakegu Bardeetako tiro eremuaren inguruko guztiak garrantzi berezia zuela bi gobernuen arteko erlazioan. WikiLeaksek filtraturiko kable batean azaltzen denez, Tuterako gertaerak baina egun batzuk lehenago –1979ko apirilaren 30ean– Manuel Gutierrez Mellado espainiar presidenteordeak telefonoz hitz egin zuen Edmund Muskie AEBetako senatariarekin, esanez Bardeetako eremua “urte askoan” utzi ziela amerikarrei, eta hori kontuan edukitzeko euren arteko “harreman berezia” estutu zedin.

Mugimendu antinuklearrak ere kezka sorrarazten zuen eta Madrilek azalpenak eman behar izan zizkien AEBei Gladys Del Estalen heriotza zela-eta. Kableetan inplizituki onartzen dute hilketa izan zela, slaying edo killed hitzak erabiltzen dituzte, besteak beste: “...was shot and killed by a civil guard”.

.jpg)

José Martínez Salas guardia zibilari 18 hilabeteko gutxieneko kartzela-zigorra ezarri zion Iruñeko Lurralde Auzitegiak 1981eko abenduan, bere arduragabekeriak Gladys Del Estalen heriotza eragin zuelako –Espainiako Auzitegi Gorenak 1984an berretsi zuen kondena–. Ez dakigu kartzelan egonaldirik egin ote zuen, baina ARGIAk jakin duenez, zigortua izan eta bi hilabete eskasera kondekoratu egin zuten.

Bagenekien Martínez Salasek sari bat jaso zuela 1992an, zehazki Meritu Militarraren Gurutzea, Tuterako alkate sozialistaren eskutik jarria. Erabaki hori oso kritikatua izan zen eta kondekorazio bidegabeen adibide gisa aipatu izan da sarritan. José Luis Corcuera Barne ministroak Madrilgo kongresuan azalpen publikoak eman zituen: guardia zibil horrek kondena beteta zuen ordurako eta 1987tik aurrekari guztiak bertan behera utzi zizkioten “tatxarik gabeko” jokabidea izan zuelako; hortaz, ordainsari hori jasotzeko eskubidea zuen.

Baina Larrun honetako ikerketan deskubritu dugunez, Martínez Salas guardia primero-ak beste domina edo gurutze bat jaso zuen askoz lehenago. 1982ko martxoaren 20ko Estatuko Aldizkari Ofizialean ageri da bere izena: Guardia Zibilaren Merituaren Gurutze Zuria eman zioten 1982ko otsailaren 15ean, Juan José Izarra del Corral Barne idazkariordeak sinaturiko erresoluzio baten bidez. Hau da, zigortua izan eta bi hilabete eskasera.

.jpg)

Corcueraren justifikazioa hankaz gora jartzen du domina horrek, 1982an agenteak oraindik ez baitzuen zigorra beteta, eta legezkoa den argitu beharko litzateke. Epaiketaren ondorioz emandako kalte-ordain baten antza dauka bederen.

Legitimitatea ere oso zalantzagarria da, are gehiago Gurutze Zuria jasotzeko baldintzak irakurrita. Dekretu aurre-konstituzional batean oinarritzen da, eta guardia zibilak “aparteko gaitasun profesional nahiz gizalegezkoak” erakutsi behar ditu eta “jokabide eredugarria” izan.

Bigarren aldiz onartu dute abusu-polizialen biktimak aitortzeko legea, Nafarroako Gobernua sostengatzen duten lau alderdien babesaz. 2015ean beste lege bat onartu zuten, baina Espainiako Konstituzio Auzitegiak baliogabetu egin zuen. Oraingoan saiatu dira legeari izaera administratiboa ematen. Alvaro Baraibar Bake eta Elkarbizitza zuzendariaren ustez talde politikoek “ahalegin berezia” egin dute “onartutako testuak biktimen eskubideei erantzun diezaion eta indarrean sar dadin Konstituzionalak inpugnatu gabe”.

Hedabide honen galderei erantzunez, Baraibarrek azaldu du biktima bakoitzarekin egin dutela lan, “bakoitza bere testuinguruan kokatuz, inongo nahasketa eta diluziorik egin gabe”. Urrats garrantzitsuak eman dituztela dio, “nahiz eta zailtasun asko izan ditugun”.

Hain justu, 2019ko urtarrilaren 10ean erreparazio ekitaldi bat egin zuten Iruñeko Baluarten, José Luis Cano, German Rodríguez, Mikel Zabalza eta Gladys Del Estalen oroimen familiar eta instituzionalaz NUPeko ikerlariek egindako azterlana aurkezteko: “Asko izan ziren bertaratu zirenak –dio Baraibarrek–, gai honen inguruan dagoen interesaren isla izan zen”.

.jpg) Google Mapsek ez du ezagutzen Gladys Del Estal kalea Tuteran, beste izen bat azaltzen da bilatzailean. Adibide txiki horrek frogatzen du biktimen “existentziarik eza”, Karlos Irujo antropologoren ustez. Ekintzaile ekologista hil zuten zubian monolitoa jarri orduko kendu egin zuten guardia zibilek; haren aldeko plaka txikituta azaldu izan da behin eta berriz.

Google Mapsek ez du ezagutzen Gladys Del Estal kalea Tuteran, beste izen bat azaltzen da bilatzailean. Adibide txiki horrek frogatzen du biktimen “existentziarik eza”, Karlos Irujo antropologoren ustez. Ekintzaile ekologista hil zuten zubian monolitoa jarri orduko kendu egin zuten guardia zibilek; haren aldeko plaka txikituta azaldu izan da behin eta berriz.

Donostian, Kristina-Enea parkea Gladys-Enea izendatu zuten egiatarrek berehala. Toki triste eta ilun hura garbitzen aritu zen Gladys auzotarrekin batera. Han dagoen hilarriari ere lehergailua jarri zioten hasieran, baina geroztik bere horretan errespetatua izan den bakarretakoa da. Ofizialki, Gladys Del Estal pasabidea dago orain parke barruan.

Greenpeaceko kideak Dakota Acces oliobidearen aurka protesta egiteagatik auzipetu dituzte eta astelehenean aztertu du salaketa Dakotako auzitegiak. AEBko Greenpeacek gaiaren inguruan jasango duen bigarren epaiketa izango da, lehenengo kasua epaile federal batek bota zuen atzera... [+]

In recent weeks we have been reading "proposals" for the recovery of the railway line Castec-Soria and the maintenance of the Tudela train station in its current location, or for the construction of a new high-speed station outside the urban area with the excuse of the supposed... [+]

The restoration of the natural characteristics of the beach of Waukee began three decades ago and continues without interruption in the staged restoration to counterclockwork.

Samuel (Bizkaia) is an exceptional space, very significant from the natural and social point of view... [+]

The update of the Navarra Energy Plan goes unnoticed. The Government of Navarre made this public and, at the end of the period for the submission of claims, no government official has explained to us what their proposals are to the citizens.

The reading of the documentation... [+]