"We still feel criminalisation, both towards immigrants and towards the most disadvantaged peoples"

- The film Camarade Curé is dedicated to Basque political prisoners, especially the Lorentxa Beyrie Dam in Kanbo. It premiered in January in the film Le Séøre de San Juan de Luz. In March, they will return to Donapaleu, Donibane Garazi, San Juan de Luz, Kanbo and Maule. We interviewed Pierre Prouvèze, author of the work.

The author is excited about the reception that the documentary has had throughout her history. It also hopes that it will take place in San Sebastian and Bilbao. As far as openness by France is concerned, it is more difficult, as much money is needed in the dissemination: “The work of the friends and friends of Euskal Herria has been essential for the projection of the film: Thanks to Mikel Epalza, Gexan Lantzi, Pantxika Erramuspe, among others...”. He has also expressed words of thanks to the Basque Cultural Institute (EKE).

Who is Pierre Prouvèze?

I'm a Marsellés based in Lyon, because at four years old we changed family to live in Marseilles. I have been a professor throughout my life and, above all, I have advocated education. I was educated in the northern districts of Marseilles, banlieue suburbs, difficult and hostile neighborhoods. I taught French to migrants. In a room of 54 square meters, I listened to 50 foreign languages. It was a heavy job. Fortunately, I turned music into an indispensable resource for language teaching. I created songs – along with other classmates – and also palabras.Con four or five years already made us sing my mother on her way to school, I bring the music in my bowels from a young age. Later, at maturity, in 1985, we created the association Les Amis de Chansons de l’Evenement (Friends of the Songs of Events) with Alain Laurance, a railway worker and humble person.

‘Camarade Curé’ and

‘No, I don’t want’ songs are alive,

the problems of their time and actuality have not changed

What is the nature of this partnership?

Since its inception, the idea of partnership has been to work for the most disadvantaged sectors. Today we still hear “everything is OK” in rich environments, but we still feel racism and criminalization towards many people, both immigrants and the most disadvantaged peoples. Around 1968, due to the oppression that was taking place in Euskal Herria – during Franco’s dictatorship – we wrote several songs. The songs were especially made to sing in the street. That was our specialty, working on the street, “taking the street”. Between the week we worked a lot, and on Saturdays and Sundays we sang in the port and in the old town.

Have you been a secular teacher? How did you experience religion?

Religion is part of my teenage education. I was a seminarian for six years. I left the church and was a professor at the age of twenty. I was and am from the left, but with a particularity: It was on the left before the famous May 1968. In other words, I and my environment were not supporters of the Communist Party. We were mostly Maoists. Our struggle was linked to the land, to the struggle in the neighborhoods and in the fábricas.And we were from neighborhood to neighborhood, from workshop to workshop, from door to door, and we were talking about the labourers. However, I must acknowledge that, despite being a militant, that struggle was a “difficult” task for me. I realized that I wasn't born to "fight," that I wasn't a regular militant. I picked the song, the music and the word to fight.

When did you get the first news from Euskal Herria?

When I was 15 years old, in 1963, I was at the seminary. I met Priest Henry Tomei, who increased my passion for the song. He had just arrived from San Francisco, California, and he talked to us about the Basques. We asked him to sing in Euskera, but he didn't know the songs in Euskera, but he taught us the score of a music girl, and he taught us to sing it. We learned that 5/8 was the Basque Zortziko, that is, the famous rhythm of Basque dance and music. That was my first knowledge of the Basques.

Later, in 1978-1979, I participated in the committees for Basque prisoners and deportees. The refugees Mikel Goikoetxea and Martín Apaolaza were confined in Valensoles, where the Spanish Government requested their extradition to Spain. When they were free from judgment, I was out waiting for them, because I was one of the few who had the car. They asked me to take me to Aix en Provence. I traveled with Mikel, my partner Izaskun Ugarte and Apaolaza. We arrived and I asked them: “What is your first wish?” “We want to eat ice cream,” they told me.

We will focus on the documentary Camarade Curé. When did you know the songs No, I don't want and Camarade curated that they are the basis of the film?

At the Toursky Theatre in Marseille in 1975, I first heard the two songs. Colette Magny sings Le pêtre interdit... (The forbidden cure) was singing enthusiastically. It was terrifying for me to hear what the song was saying. “No, I don’t want that civilization.” Inside Magny's song you heard Ez, ez dut nahi -- out loud in the choir. For the first time, listening to words in Basque was exciting for me, and it was wonderful for us to learn more about the Basque reality. Then, our favorite singers were François Béranger, Léo Ferré or Jean Ferrat, and among them Colette Magny.Los members of the association Friends of the Songs of Events we decided to include Camarade Curé in our repertoire. However, I would like to stress that this decision was not easy. The song Camarade was not accepted in all sectors. Colette Magny was banned from singing in several rooms.

How did the project of making the documentary begin?

Martine and I were particularly interested in knowing the origin of Magny's song (No, I don't want Julen Lekuona's song). In 2016, in [Lapurdi], Collete Magny was honored. Beñat Achiary invited us and approached the world of the Basque singers. We knew Achiary before, as in 2014 he sang in Marseille the hymn of Black Panthers singing Collete Magny.

We also learned in Baiona that the Kantuz street group sang Ez, ez dut nahi. I wrote to manager Guillaume Irigoien asking him “permission to roll while they were singing in the streets or in public places.” At the same time, I met with the Basque Cultural Institute (EKE) and presented the project to him. They told me it was a traditional song, they looked at me in awe. I was recommended to go to the Agorila discography. The record player, Manex Meyzence, “is a collective, popular song with no own author,” he told me. Meyzence said it was like this on his album "harshly." I kept tracking, and I knew the song was "Julian Lekuona." “Look, you’ve been robbed of authorship and named it as a popular song,” I thought. Xabier Amuriza later confirmed to me that the song's author was Julen Lekuona. For me, clarifying and learning everything about the song has not been easy.

Why do you say that?

For example: I told EKE's friends that I wanted to meet Xabier Amuriza. They gave me their e-mail and I wrote it immediately. A few days passed without anyone responding. I went back to the EKE secretary and said, “Have you received a response from Amuriza?” I asked him: “No.” “In what language have you written?” he says. I asked him: “In French.” He made me a gesture of doubt. I understood that I had to make a special effort. I searched for a dictionary online: French/Basque. I returned the text to him. Think about the Basque language that was written. But the next day, I got the answer from Xabier, in Basque. And I, from Basque to French. I think at first he took it on a “crazy” issue. However, fortunately, the priest Mikel Epalza became an intermediary. Epalza helped us. However, I think neither of us expected the Camarade project to be a film.

We know the omertal situation of minority peoples and cultures, it is

not easy to talk about the Basque problem.

What's the movie like?

Technically, it's a simple film, it's not a work of art at all. As my friends say, “our desire is to convey the value of popular culture, we do it above all.” I'm an amateur filmmaker, trained in popular culture. For us -- the film I haven't done alone -- to tell this part of the story was on the way to our desires and aspirations. We've looked at the lives of Magny and Lekuona, we've worked on them and -- in a small part -- we've made people known through this film.

Has it been hard for you to carry it out?

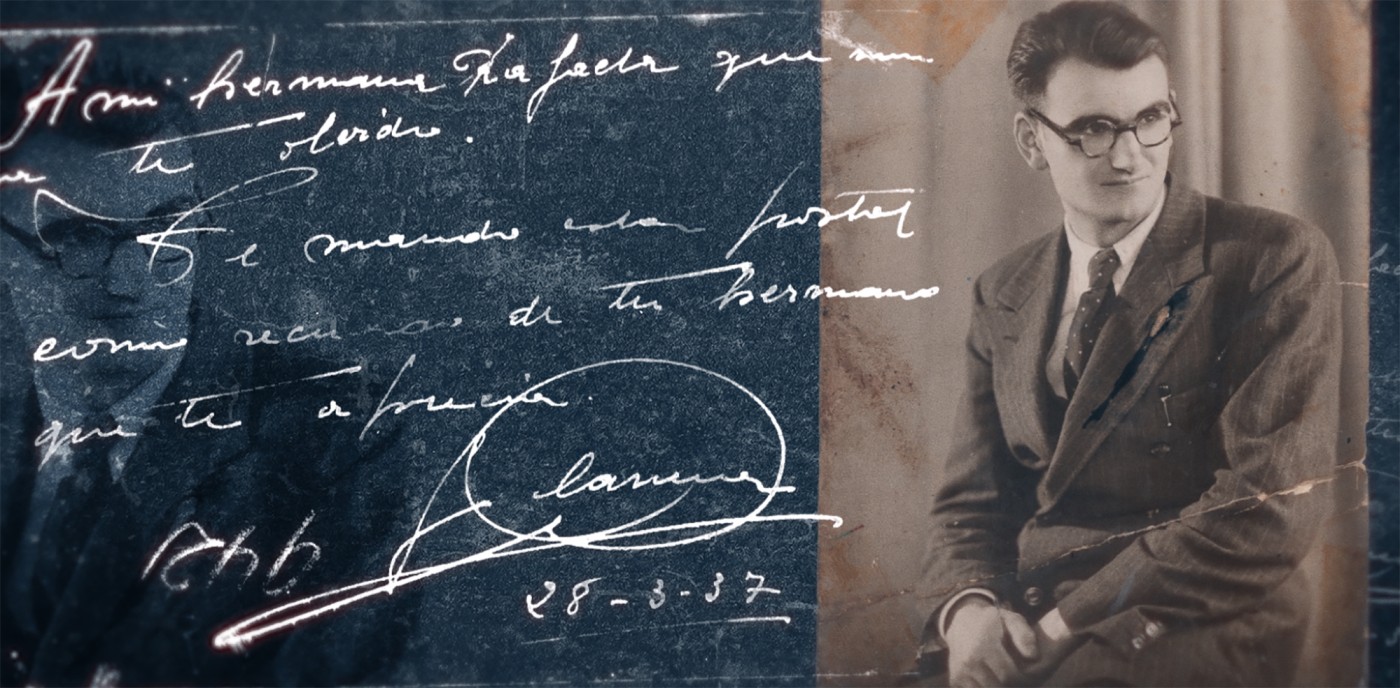

We've had difficulties, because to start with, there's no archive of the time. Thanks to Juan Mari Arrangi we have been able to get some photos, Amuriza has also passed us some, but since the time of the Derio Seminary there is almost nothing. According to Arrangi, at that time it was very difficult to photograph the demonstrations on the street, because, on the one hand, there were few cameras and, on the other, the police were always on top. One of the Police ' s objectives was to prevent photographs from being taken. “The camera should not be seen for a moment,” Juan Mari told me.

On the other hand, I looked for a producer in Marseille to make the film. “It’s a nice story, very significant, but you’re not in our editorial line,” they told me. In other words, the Basque issue is not on its agenda, they do not like it. Although I made many proposals, I found nothing but drawbacks. So, the truth is, I haven't had resources, and I decided to do it in a humble way, with few resources. I've done what I know how to do with the help of my friends.

You've joined Collete Magny and Julen Lekuona through a song.

It has not been difficult or difficult to understand. They both worked on the same logic of the song. Both Lekuona and Magny wrote songs about the sociopolitical situation experienced by both, similar situations, their songs were “questions”, they made “protest”, they were committed singers, they asked the working class… Moreover, Julen asked “if they wanted to live in that lethal state”. His people were about to die and asked, “What to do?” In the film, we've collected the two stories, which were actually in the same line as history. Large producers can make with great resources a better film, an author or a cult film. Ours is not, but it had to be. We wanted to bring together singers and activists from two different cultures. Camarade Curé y Ez, ez dut nahi kantak bizirik dago, we have shown that the problems of their time and their current situation have not changed.

Well, the film will show up in Marseilles. How do the marselleses see the Basque Country?

In Marseille there is the Basque Country Etxea. In Marseille there are some 30,000 Basque surnames. However, in Euskal Etxea there are few partners, about 30 people, very few. Once we were called to sing [Les Amis de Chansons de l’Evenement]. Now they also want the film to come and talk about it. But it is not a collective issue, but at the request of a single member of the Euskal Etxea. Not everyone looks at us with good eyes. For example, on the part of a partner, I have had to hear that my intention is to “make political propaganda.” “No,” I said. That I am not a Basque, that I do not want to lecture the Basques here and there. And I said, "It's amazing that the Basques who lived out are so uninterested in what's going on in the Basque Country."

The so-called “Basque problem” is difficult to understand in France...

Yes. We are travelling through several French regions and we know the omertta with minority peoples and cultures, the omertta is very obvious, it is not easy to talk about the Basque problem. In Marseilles, as far as I know, the Basques are divided, but that is not the case only among you. In most of the communities I know, almost all of them, there are always divisions. Not everyone thinks the same, but at least we have to learn to listen to each other. To that Basque of the Basque Country Etxea, or to the Basque of origin, I said with kindness: “We don’t think the same, OK, yet you’ve only got some ‘interested’ echoes about the film. But I want to pay tribute to those two singers who came together through a song. Just make known what they were.”

It may seem to some that a documentary has been made in favour of one of the parties to the conflict.

I want to underline two things, and I wanted to do so in the film. On the one hand, Basque prisoners must be regarded as political prisoners, and that is why we cannot forget the victims who have been in the conflict. The victims deserve all respect and empathy for them. We have made room for the peace process in the film, making known the situation of today ' s prisoners.

It is true that in the film we have received an act in favour of the prisoners, we wanted to show our support for these prisoners and their families. The act of support for the prisoners of eta lasted for 90 minutes. We have taken particular account of the history of the Lorentxa Beyrie dam. The paintings painted by Lorentxa were shown in the act. Her mother was there and she said "sensible words." However, there was another reason. Mikel Epalza told me they were going to sing the song Ez, ez dut nahi dut. In the film, we wanted to bring together the situation that the song brought about in an act of support for today's prisoners, nothing more. Surely, the associations for victims who have generated the conflict want the same respect for them. As I said to Mikel Epalza, “the documentary is open. I would like the testimonies of all the people hit by the conflict to have a place.”

.jpg)

Marseillarra da. Irakasle aritu da 37 urtez. Irakastea izan da bere leitmotiva. Musikak eman dizkio irakaskuntzaren zentzua eta bizitasuna. Ez du bizitza ulertzen musikarik gabe. Kantuak berriz, Camarade Curé dokumentalaren egilea izatera ekarri du.

Itoiz, udako sesioak filma estreinatu dute zinema aretoetan. Juan Carlos Perez taldekidearen hitz eta doinuak biltzen ditu Larraitz Zuazo, Zuri Goikoetxea eta Ainhoa Andrakaren filmak. Haiekin mintzatu gara Metropoli Foralean.

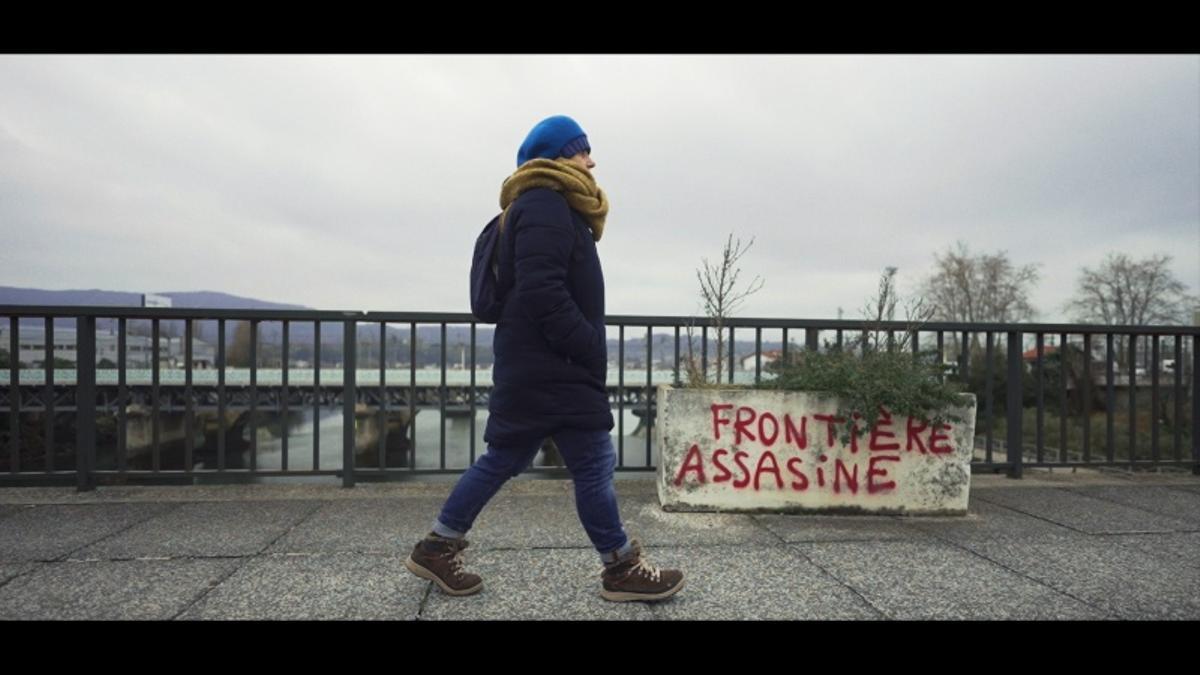

Projection of the documentary Bidasoa 2018-2023

Where: Martutene prison, Donostia

When: Friday, 22 December, 16:00h

Available as a network: Perfect on the platform

------------------------------------------------

It's Christmas. Friday after lunch. Let us go through the long... [+]

FIPADOC Nazioarteko dokumental jaialdia berriz heldu da Miarritzera. Urtarrilaren 19tik 27ra ospatuko dute, eta seigarren edizio honetan «Italia eta Afrika» izanen dira protagonistak.

Hands have a varied symbology. With hands the world is driven and with strong fists the command is supported. Power also fights with fists, picking fingers and raising hands up. Hands are necessary for those who have always been the losers of life, for that alone has been an... [+]

Lana finantzatzeko diru bilketa abiatu dute; ahalik eta gehien zabaldu nahi dute ikus-entzunezkoa, protagonistak sufritutakoa ezagutarazteko eta torturak salatzeko. Bi arnas kontatzen dira, torturaren eraginez itxi gabe dauden bi zauri: Sorzabalena eta haren ama Maria Nieves... [+]

Mikel Zabalzari buruzko Non dago Mikel? filmak Urugaiko Nazioarteko Zine dokumentalaren festibalaren sari nagusia irabazi du, AtlantiDoc Saria hain zuzen ere, dokumentu-film luzerik onenarentzat.