Hundreds of workers on the street and nothing happens here.

- Homeworkers are on strike and protest. Most of the springs of the precarious and feminized sector have:hard physical work is not taken into account; institutions find it cheaper to give economic benefits to family members or dedicate to the sector to foreign women; they have no Sundays. Construction companies have been included in the sector, subcontractors who do not know what it is to serve dependents.

PILI Larrañaga, Jone Fernández and Ana Martínez work for the company Garbialdi de Donostia. They're members of the LAB syndicate. Alicia Graña, for her part, works in the home help services of Bizkaia and is responsible for the CCOO union of the Basque Country. “It is a feminized profession and therefore also precarious,” says Graña. Larrañaga, Fernández and Martínez coincide. The last three have protested since September last year with the aim of improving their labour and social rights.

The City Hall of Donostia-San Sebastian has put the home help service to tender. Before, they wanted to reach an agreement and sign it with the company Garbialdi. After several attempts, and in the absence of progress on the part of the company, an indefinite strike was called: “They told us that the demands of the unions were abusive, but they did not make any other proposal.” In the end, they have not reached an agreement. LAB representative Iker Beristain explained that four companies have been submitted to the competition and that it seems that the Aztertu company will win: “The company was studying before Garbialdi and the workers say the relationship with them was noticeably better; of the worst we could say it is the best option.” They are therefore hopeful because if you win the Aztertu competition you could have the chance to sign a new convention.

But what improvements would you like home staff at Donostia/San Sebastian to collect in the convention? For example, wage increases: Those earning less than EUR 1,500 will have EUR 30 more and those earning more than EUR 1,500, EUR 15 more. Those who work throughout the week work from Monday to Saturday, so they want the working week to be Monday to Friday. Weekend workers are not paid more for working on Sundays.

They require payment of a shift between services. This has been explained by Beristain: “If you have seven one-hour-a-day services, you get paid seven hours, but at work you may spend nine.” That is why workers are obliged to stay free for eleven hours. Larrañaga says that he works in the neighborhood of Amara de Donostia and that he has to make a section of Amara, Loiola, Martutene and Aiete: “I need a lot of time going from one bus to another.” Martinez also moves in this way in the Gros district from one end to the other. They are not paid for services that are cancelled: “If you have to go to a house at 15:00, but the dependent person is in the hospital, you have to wait for the next service and do not take that part of the time into account.” Beristain says the situation is unacceptable: “For example, the cleaning agreement is included.”

Graña explained that in Bizkaia the situation is different: “Unlike in Gipuzkoa, we have a territorial agreement and therefore are better conditions.” However, they are not satisfied: “We demand many social improvements.” 99% of the people who work in the sector are women and believe that this “inevitably” means the “precariousness and disprestige” of the profession. In the case of home workers in Donostia-San Sebastián the same applies: There are 350 workers and 15 of them are men.

Graña has set the following example: “Our work is physically very hard, we have to gain a lot of weight, but that’s why we have no benefit. For example, in many male works that are physically hard, they retire earlier.” He believes that being a feminized profession makes all this effort invisible: “We have to lift people out of bed, wash and move them, and most of the time alone, without any help.”

Economic benefit for family care?

It also says that it is necessary to criticise the positions of the institutions: “In recent years, our company has expelled 500 workers. What's that like? Do we have more and more dependents and fewer workers to take care of them?” It considers that public institutions – sometimes the city council and others the council – are leaving responsibility in society. “It is cheaper than providing home-based services to provide an economic benefit to families to take care of the dependent person.” She adds that, in most cases, they are women, mothers, sister, sister or daughter: “Or, if not, they will hire a foreign woman to work in worse conditions.”

Graña believes that this only occurs in the area of care and in the feminized professions: “For example, the sweepers are hired by the city council and do not give a financial benefit to the citizens to take care of the cleaning of their street section, right?” On the other hand, it has denounced that, despite the loss of 500 jobs in a sector of this kind, it is not noticeable on the street: “What about the shipyards? They dismiss several workers and everyone goes out on the street.”

The home workers of Donostia-San Sebastián also consider that the institutions should act "more responsibly". “Are they the ones who outsource the companies that are in charge of home help, give them EUR 10 million and have nothing to say in their decisions?”

Working with people or bricks?

Beristain and Graña recall that many of the companies dealing with home services are construction companies: “How is that possible? We work with people and they think we walk with bricks.” In the same vein, Larrañaga has spoken: “We work with people with all the burden that this entails, for some we become the most important people in their lives.”

Although the work is organized as if they were in the factory, Fernández, Larrañaga and Martínez have repeated over and over again that they work with people and also in their homes: “We enter people’s homes, open the doors of their lives and create relationships,” they explained. They add that although technicians pass or can go to the Social Worker, it is they who spend many hours every day with dependents – and their families –. “Some are old, some are young and, in some cases, even children,” says Fernández. In this regard, he stressed that workers are affected "a lot": “It has once happened to us to know through the plague of his death over the years caring for a person.”

They believe that it is necessary to stop operating as companies operating machines and they are clear that subcontracted organisations and companies must inevitably adapt to the needs of the sector. In the meantime, trade unionism will continue to fight with the intention of signing new agreements for workers and users.

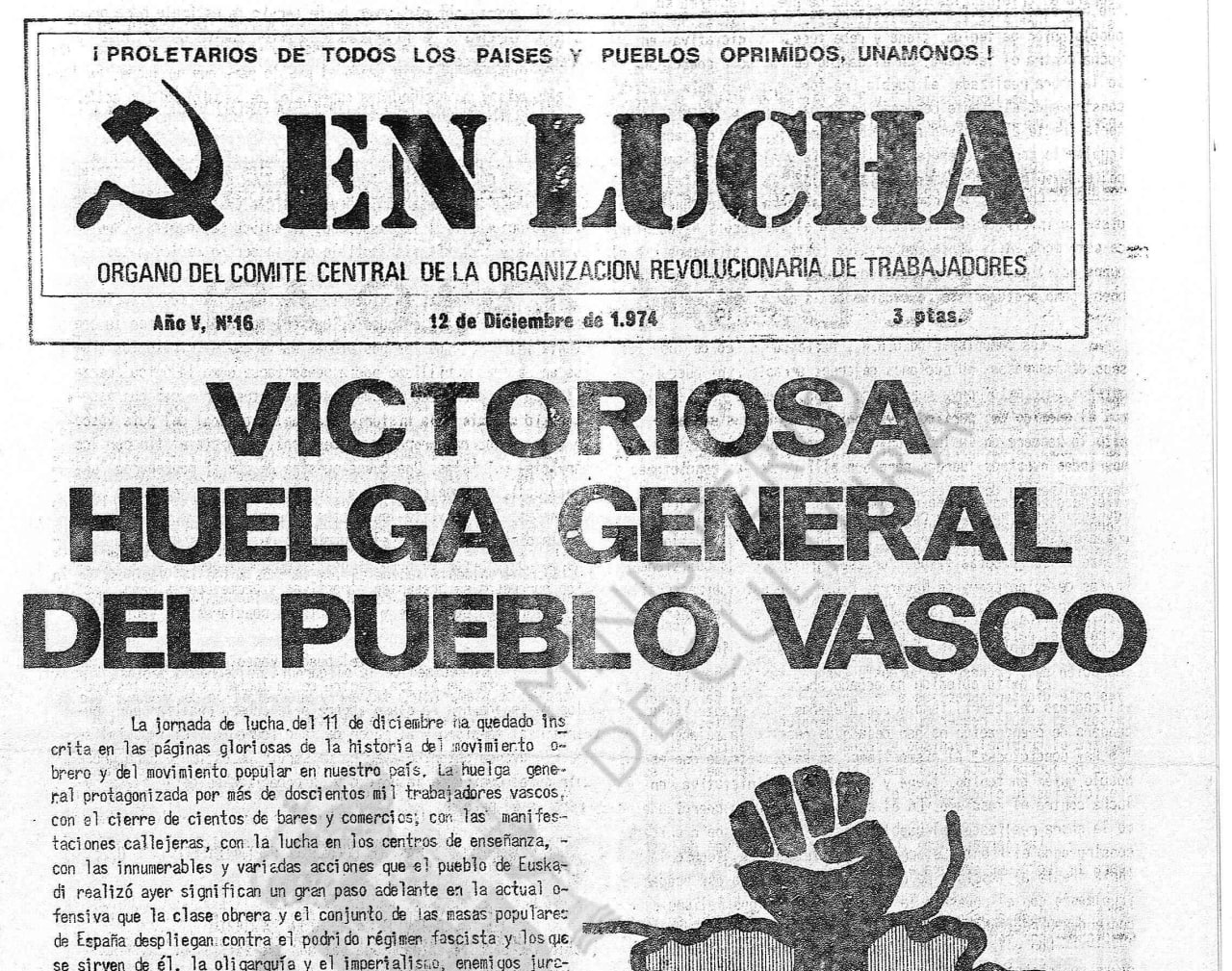

Today, 50 years ago, the labor movement of the Basque Country wrote a very important chapter in its history. In Hegoalde, some 200,000 workers went on a general strike in protest against the Franco regime, which lasted two months. This mobilization made it clear that the... [+]