More real than reality

- Since she published Twist (Susa, 2011), Harkaitz Cano, who had not published novels, returns with a bet as strong as her: The voice of the faquir (Susa, 2018). The program will investigate the life of Imanol Larzabal, who has portrayed four decades of great ups and downs in his career. We met him in Donostia, with a series of questions in the hand that the book has left us.

“It should be made clear that our responsibility is not to bring reality, but to invent references to something that is thinkable and cannot be represented,” wrote the philosopher Jean-François Lyotard. If we talk about the novel Fakirraren ahotsa, the phrase makes a lot of sense. Part of the trajectory of singer Imanol Larzabal has known the performances, his real story has been told to us. It may be approximately: He was a member of ETA, so in his youth he had to leave Euskal Herria; from understanding music as a way to militate, he started to value art, he became a singer and nothing else, although he did not abandon his political commitment, neither when he helped the flight of Joseba Sarrionandia, nor when he stood against ETA, after the murder of Yoyes, and for the second time.

This account has been made on television, in the press, in the events organized to commemorate Imanol. But is that all you have to tell? What remains unrepresented? What can't be represented through the usual ways that we use to bring reality? In short, what possibilities does a novel, fiction, have, that have no genres based on contrasting data – biographies, documentaries –? Fakirraren ahotsa offers the reader a possible answer to these questions, counting the four decades of life of the character Imanol Lurgain. Ficticio Imanol: no real, yes real.

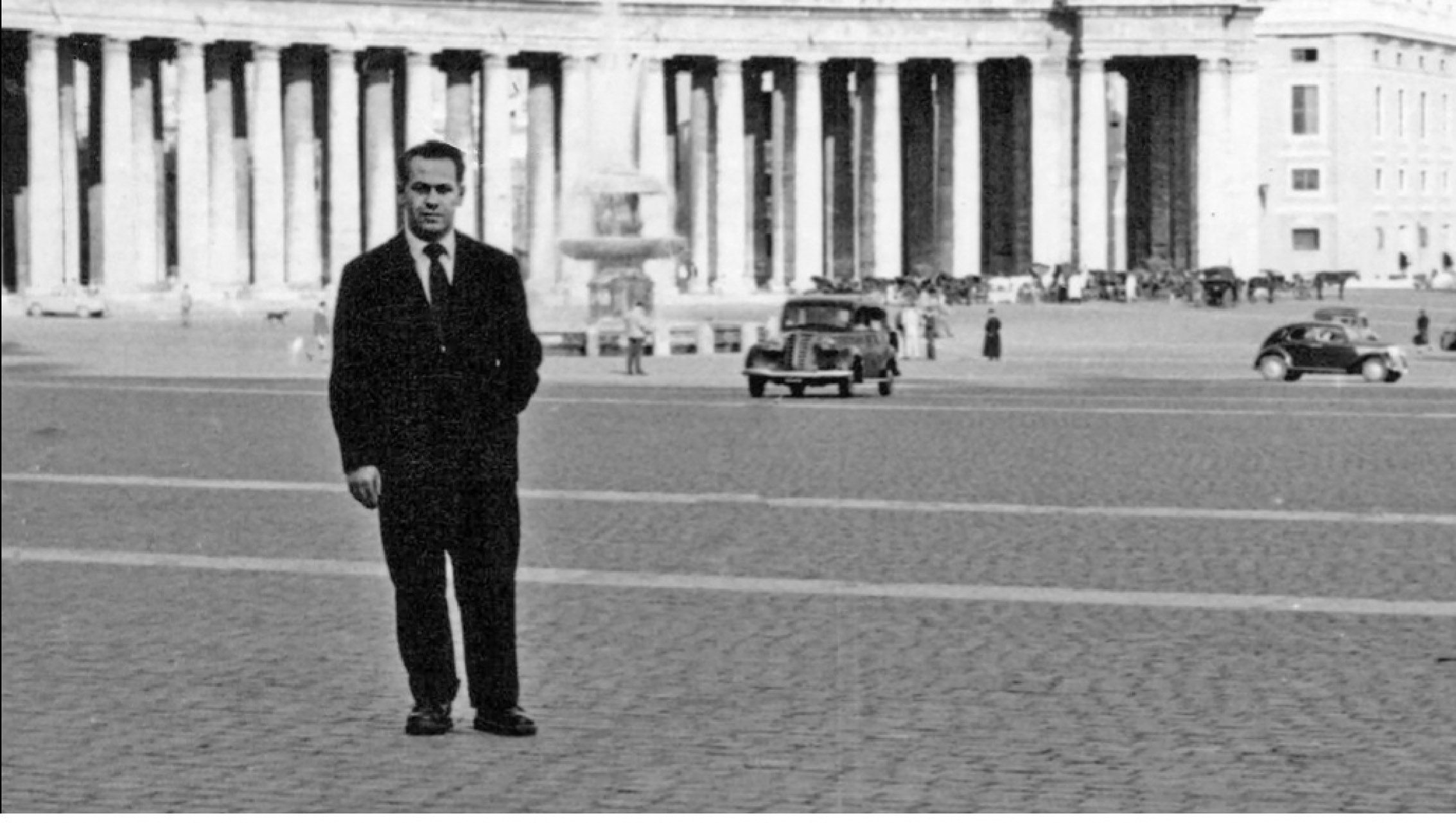

In 2017, while writing the novel, we received in writing a message from Gorka Arrese, editor of the editorial Susa: “I look for the pictures of Imanol Larzabal and then make an art cover to the novel. Are your old photos still stored in the ARGIA photo archive?” When he came to search for the images, he explained the huge documentation work that Cano was doing. We've started the interview by asking about this process.

How many interviews have you conducted to collect material for this novel?

I think it's been about 30.

And how did you think about the relationship between the fiction I wanted to tell and the reality that it's been based on? With this material by hand, it has not slipped into journalism or the documentary.

Probably by elimination. I do not know how to work as a journalist. The material I had was for journalism, but many things were complicated to prove depending on the journalistic parameters, as they were testimonies, stories from many years ago, different versions… To write the novel I have not used the data so much, but the mutations of subjective perceptions. When you interview people, even if it's a subject and an objective, people tell you their life, rather than questions about the subject you're researching. And I'm a very demanding journalist: I let people talk, my urge is not to interrupt or say, "but you've said this before, and yet now you say this," that work I haven't done. I talked to people, I didn't record anything, I took notes in such a notebook (telling the journalist he's taking notes) and I did two or three of these. But then I realized that I rarely played the notebooks, unless I was looking for concrete things. Because I wasn't interested in the data, the exact chronicle, where and when he was with whom.

In the first chapter and in the last one your head appears. Has it been a way of showing that process that he mentions?

It can also be an example of discharge, saying that “I am a writer and the writers work this way, that is, the sacrilegious I have done”. The story of this tape that appears in the first and last chapter is real, it exists, and what I'm telling you about that tape is what it really is. It wasn't quite that way, of course; it wasn't with Jean Pharos, but with Joxan Goikoetxea.

Why Imanol Larzabal?

For two things: on one hand, as the jazz standard says, “for sentimental reasons” [for sentimental reasons]. Here lived Imanol [pinpoints a street building where we are doing the interview] and I was in that house. Imanol didn't live there at the time, but there were still some things left of him. It was a coincidence, my aunt lived there renting a house. And as a child, I would be about ten years old, that house had nothing to do with the other houses I knew: round windows, cushions on the ground, oil paintings on the walls, lots of discs on the floor… I have that memory of the first time I met an artist’s house. And then they said to me, “Imanol lives here.” I didn't know who I was. And later I heard the music of Imanol -- he was very young, he could hear Serrat and Imanol and he could hear Kortatu and Zarama -- his songs I liked in adolescence, especially the romanticism of all pores. My way of reaching poetry was also that, by saturation, not knowing that it was poems that sang Imanol, those of Koldo Izagirre or Xabier Amuriza. For starters, I had a bond, the attraction to a special character. And on the other hand, there's the story that we all know, that almost circular, hard account of the Greek myth that we have of Imanol, with that raw ending, I wanted to know if it really was, or to what extent it was.

Interesting contrasts can be found between the voice of Faquir and, for example, the absence of Imanol within ten years of Imanol's death between PAUSOKA and ETB.

I know that documentary, it's pretty good...

… I found it paradoxical that the novel shows a different truth than that based on real facts and archival images.

I think Antonin Artaud said: “Never real, always true.” Between reality and likelihood, my choice is clear. In addition, the closer you get to reality, the more I'm interested in it. To me, at least, factual things don't matter so much to literature. Speculation serves me the most after the subjection of a story narrated by a person, that's my field, I'm there to taste, that allows me to move away a few times and get closer, in this case to a real Imanol. The transfer there I have never lived in this way: the transfer between your character and you, what he gives me and him, what we take with each other in borrowed clothes.

Imanol understands music as an instrument of struggle. But then it changes, it wants to be a musician.

The evolution was curious. In Paris, he radically changed his vision of what he was doing, and it's interesting how he came to it, because he met several very key people and helped him along that path. Because it seems that the artist discovers everything in his loneliness, but talking to people you realize how he met several people and how they taught him the way, they helped him, they gave him good advice: The case of Paco Ibáñez or Martina, for example [in the book is called Tatiana the woman Imanol knows in Paris]. I wanted to fade away that mythical loneliness of the artist, the outline of that construction that I wanted to illuminate, which is kept in the shade.

It is striking how the murder of Yoyes in Arakis has been reported, with this rewind effect. Did you think a lot about how to write that scene?

-I was about to abandon this novel. We talk about failure, it's

very nice, but when you really have the feeling that you're fractioning, it's hard for

you to abandon the projects."

Maybe it's the only stylistic experiment in the book, the only one that can be fascinating. I was spinning around things like records, cassettes, rewind, self-reverse, zone A, zone B, intro... I wanted that kind of thing to have its reflection on the structure of the novel, and I saw a moment for that, where it could make sense. The murder of Yoyes has been a key moment in the last 40 years. I was 11 years old and I remember, as if it had been yesterday, that in the kitchen we were listening to Mariano Ferrer on the radio. But I don't know how I got to that moment in the novel: two or three weeks ago I was with Anjel Katarain in Ordizia, we walked up and down the plaza and maybe it emerged there, with that walking movement almost. “This happened, but it could happen that it wasn’t,” I thought. “And how many people I wish it hadn’t happened.” I was slowly trying to get into their heads. And that's how I came to tell it. At one point I thought about taking it off or telling it differently, but now I've realized that a lot of people have stayed with it. “You can’t ask people to read a book twice, but you can give it the text twice,” I thought. Why not? Why do we do so few experiments? Sometimes we come together. Too much. And the truth is, I was very comfortable looking for that effect, some phrases that might work in a similar way forward and backwards, but with different echoes. I wrote that in Getaria, when I thought I was finishing the novel, but…

In fact, this book was expected last year.

I, too [laughs]. I was about to quit. We often talk about failure, it’s very nice – “refrain again, fail better”, as Samuel Beckette said – but when you have a feeling that you’re really crashing, you have a hard time leaving the projects. I've already left a couple of them, and this was also one of them, who had the risk of putting them aside. Then it gave me strength to think that, after talking to so many people, I had a debt – although some of the people I was talking about seemed not to like it.

Did you feel it? What people you've interviewed won't like?

Rather than like it, when people tell you stories, they expect to find the same stories that they told you in the book. And I was trying to explain to him that this was a novel. But it's useless, people want to see what they've told you, it's logical; and they might see it, but not as they expect. People met him very closely, and most of all, people who met him at a very specific moment, have very much in mind some memories and events, but of course, talking to people who met him at different times in his 40-year career, they tell you very different things. My job was to govern everything. And that, along with the mutation of fiction, generates some sensations in those who knew it close, let’s say, “this wasn’t so.” It's a toll to pay.

Joseba Sarrionandia's flight is another passage that has an important place in the collective memory. But you said that differently.

Those who had read the book before publishing it told me: “He’s told the most frequent… It’s not… I expected more.” It was a deliberate attempt to tell from another point of view a very heroic episode. That leak has his song, his legend, his exiled writer… What could he bring there? I could have made a film, a form of escape from Alcatraz, or any other than a way of looking. But I think there is something closer to the facts than the flight of Sarri, which is in the popular imagination.

Is there also an account adjustment with Donostia in the novel? We have read phrases like “a neo-gothic cathedral that is not worth a sketch”…

The chronicler says it, but he would sign it. I've been living in Donostia for 28 years, but I came here with 13-14. It's a complicated age to be a friend of a city: I've always felt that feeling of having an love-hate relationship with Donostia. It's a beautiful, undeniable city, but do we have faith in the beauty of the city? You go to Santiago de Compostela – I was two weeks ago – and there is nothing, there are no children, there are no street stands, there is nothing. The city is with its people and their vibrations. And you say: “What a good thing.” It needs nothing, it is the city and the inhabitants have faith in the city. And I have the feeling that San Sebastian, many times, does not have faith in how beautiful it is, that we are camping in the search for the complements.

“‘War dynamics’ could be said and agreed. “Killing people is harder.” It is a phrase that gives some thought to the terrible consequences that some euphemisms may have. This is a novel going through a conflict, what is the role of words in a situation like this?

This is a very important issue for me and perhaps we underestimate it, for example, when another ETA member tells Imanol: “Won’t you believe that only with the guitar will we get away?” There's a terrible truth: history shows you don't go far with guitar alone. And then there is a humanist ideal, which we often defend, but which leads us to collide against the wall: between these two paths, who is realistic and who is innocent, and what is the consequence of being too realistic or naïve, there is the development of everyday life and history. And that this has not been articulated, that our discussion has been poor, that it has been done with the wrong words, in many contexts, we have paid it expensive. But that is the result of a poor humanist tradition. The Basque Country can also do its bit: to be able to reach the details of this humanist tradition in Basque. And I don't know to what extent we're using this.

Related to this, how do you see our cultural environment lately?

I've done what I've almost never done at the last Durango Fair: I've been there almost every day, in the morning and in the afternoon. And besides checking that it works “to sell or not to sell” – that is, that being there sells – I have realized that there is a much younger generation reading and buying books. It was a novelty to me. So far, I haven't experienced that sense of relief, of buying and buying books from 25-year-olds, and that's both made me happy and surprised.

As things stand, it doesn't seem easy for that to happen, no.

"When publishing in Spanish, there is a rather perverse and subtle dynamic that makes you feel like a subordinate writer. And I don't know if I'm willing to play that dynamic."

Iván de la Nuez has published a nice leaflet, Rearguard Theory and says that we have been sold multiculturalism as a reaction against globalization, but that multiculturalism has been the exotic phase within globalization and that is over. And it struck me as a phrase as true as the lapidary: the visibility of small languages and small cultures – a word that is so fashionable – the place we occupy or have believed to fill in the ecosystem, is very much in question. The roller is overtaking and that requires a heroic resistance that we are not oblivious to, we are trained, but there too I see the Basque culture. Very healthy in quality and quantity, perhaps healthier than ever, as Gorka Arrese says, but our articulation in structural parameters is not much stronger. Many times we live in bubbles and it seems to us that things are improving, but then “the world is broad and strange”, as Sarrionandia said. We need to be vigilant. And with language, I feel -- I've done a lot of things from time to time, because I've translated things, and I don't know if that corresponds to me. My body asks me to retire.

In what sense?

I don't know if it makes sense to translate my book into Spanish, as I'm doing now. And I've believed it has been for 20 years. But now… as a Basque creator, I don’t know why I do this. Spanish is also my language. Here's a community that lives in Spanish, yes. Yes, they're literary. Outside, someone could read it. But the sum of these four parameters I don't know if it's enough to translate my book into Spanish, as a Basque writer. I don't know if it's a waste of time. If I didn't have to dedicate more to Basque and Basque.

It has to be a problematic issue, when it comes to being a writer.

There's a schizophrenia, there's a pretty perverse and subtle dynamic that makes you feel like a subordinate writer. And I don't know if I'm willing to play in that dynamic.

Astelehen honetan hasita, astebetez, Jon Miranderen obra izango dute aztergai: besteren artean, Mirande nor zen argitzeaz eta errepasatzeaz gain, bere figurarekin zer egin hausnartuko dute, polemikoak baitira bere hainbat adierazpen eta testu.

Martxoaren 17an hasi eta hila bukatu bitartean, Literatura Plazara jaialdia egingo da Oiartzunen. Hirugarren urtez antolatu du egitasmoa 1545 argitaletxeak, bigarrenez bi asteko formatuan. "Literaturak plaza hartzea nahi dugu, partekatzen dugun zaletasuna ageri-agerian... [+]

1984an ‘Bizitza Nola Badoan’ lehen poema liburua (Maiatz) argitaratu zuenetik hainbat poema-liburu, narrazio eta eleberri argitaratu ditu Itxaro Borda idazleak. 2024an argitaratu zuen azken lana, ‘Itzalen tektonika’ (SUSA), eta egunero zutabea idazten du... [+]