A century in the mud of journalism

- There is no constant continuity between Zeruko Argia, founded in 1919, and ARGIA, but there is a fine and strong line that unites them: the desire to do journalism in Basque. This thread makes ARGIA the most veteran media in Euskal Herria. Around this thread many dreams have arisen and have been extinguished, and, by pulling it out, the magazine reaches its centenary, ready to serve another hundred years in the service of the committed and independent Basque journalism.

The Semanary Zeruko Argia was born in Pamplona in 1919, as part of the flowering of Basque culture at the end of the 19th century and the beginning of URL 0, with the hand of Capuchin monks. Father Damaso Intza and Father Buenaventura were the creators and, in the words of Intza, especially thanks to the latter, “he was tenacious”. Buenaventura went to the provincial father. “We can create a 25-page page page each month that can give us new Euskaldunes themes in Basque.” This was reported by Damaso Intza, about to turn the century, in an interview carried out in Pamplona in 1986 by Iñaki Camino. In 1918, Eusko Ikaskuntza was also founded and in his lap, in 1919, the Royal Academy of the Basque Language.

.jpg)

It was a religious journal, like most other publications related to the Basque Country at that time, and was published monthly until 1936, extended to all Basque citizens. Secularism was arousing throughout Europe and was a way of conveying the message of the Christian press to the citizens. It could not be said that this magazine and the current Argia had much in common, but shared an important component: to see and tell the world through the Basque Country.

Argia de San Sebastián

The present Argia has a double flow rate. The general information weekly Argia was created in 1921 in San Sebastian with the help of a group of Euskaltzales with the objective of bringing the Basque culture, the news of the peoples and the rural world to the Basque households. The Jesuits Ramón Intzagarai Elurmendi and Bittor Garitaonandia, Gregorio Muxika, Ander Arzeluz, Antonio Lizarraga, Anbrosio Zatarain or Ricardo Leizaola were their creators. This also lasted until the War of 1936 and, due to its character and weekly frequency, came to have a great influence on the world of vasophiles. It is said that it started to shoot 800 copies and that it had 7,000 subscribers.

Xabier Lizardi himself worked as a writer in the newspaper of Donostia and the bells of Argia were key to the project of the Basque newspaper of 1929, whose zero number was also made but was not finally published. To make the project profitable, Lizardi calculated that 3,000 readers were needed, but finally the PNV environment opted for the bilingual newspaper El Día, created in 1930, which was expected to reach more readers, and the Basque newspaper project was relegated. The first newspaper in Basque would be created between the shooting of the war, the Day, in January 1937 and would last until June of the same year.

As far as journalism is concerned, this Light has more to do with the current one; and as you can see in the first issue in the greeting written by Elurmendi, there were also more similarities. Surely the current reader is not surprised by his words: “…all the wisdom of the society that bears the name of Head is gradually being lost”. The Argia Working Group did not go very far from them when it chose the motto for the centenary “Propelling since the age of 100”.

The post-war repression of 36 brought with it a break with everything that smelled the Basque nation and the Basque culture. Between 1946 and 1948 there were fifteen numbers of the Light in Venezuela and New York. In the logic of exile, these Lights were more political and more linked to the nationalist world. Some numbers of Zeruko Argia were also published in the period 1954-1959, some of them as fortnightly by the Capuchin of Hondarribia, including Kaietano Ezeiza.

.jpg)

The weekly again

In the 1960s, and especially in the 1970s, Basque culture experienced a new boom. The repression of everything that was Basque had very negative effects, but in society numerous responses were articulated to deal with the oppression of Franco: there could be ETA, the ikastolas, the Ez Dok Amairu movement or the creation of the Euskera batua. In that oxygen bubble, the Celestial Light also grew. Under the impulse of Agustin Ezeiza, brother of Kaietano, he resurfaced in 1963, this time as a weekly, working the general information, in newspaper format and under the property of the Capuchins. In these decades, journals such as Anaitasuna, Jakin, Goiz Argi, Egan or Karmel flourished. In Ipar Euskal Herria, after the closure of the former Eskualduna magazine in 1944, the same year the general information magazine in Basque Country Herria was launched, which is still alive.

In the 1960s, Zeruko Argia went out to modern journalism. In the 1920s there was a close relationship between Zeruko Argia de Pamplona and Argia de San Sebastián, but on this occasion the same mancheta also denounces the need to combine the tradition of both: With small celestes and Luz en grande copy the typography of the Luz de San Sebastián. When the official church was on the Franco's skirts, giving importance to celestial things wasn't the best way to get closer to the citizens, but it didn't even forget what its basis was.

Ezeiza says that at the time of Franco's time it was not possible to make an open collection among the citizens, and that he had to resort to specific people in search of avalists. Due to the impossibility of doing so in San Sebastian with the information officer of Garai, he went to Pamplona to print the magazine. Many of the later great names of Basque culture began to write at that time, among others, Rikardo Arrangi, Ibon Sarasola, Txillardegi, Xabier Lete or Mari Karmen Garmendia.

The foundations of Basque journalism

These were times when journalists worked without a fixed salary. By the end of the decade, the incorporation of wages into the group began. Look at Jone Azurza, who had just finished her journalism career, was hired as a director in 1967 and worked on her until 1972, when she left the journal due to the vicissitudes she had with her work team. He had an initial salary of 6,000 pesetas and at the end of that year, 15,000 pesetas, was hired at the time by Mikel Atxaga. Luis Alberto Aranbarri Amatiño also began in the late 1960s with a Zeruko Argian of Eibar; his Zenbat Gara column became well known at that time. Nemesio Etxaniz, recently deceased Xalbador Garmendia, Donato Unanue and Begoña Arrangi are other articles of this time.

The weekly was written on Okendo Street in the Guipuzkoan capital. It was years between smoke, the strict censorship of Franco and the need to write and read between lines. In any case, the following facts may serve to understand the appalling situation: At the time of Azurza, two fines of 25,000 pesetas were paid, one for the use of the word batzoki and the other for nationality. There were also others, among them by his editorial during the 1970 Burgos trial. The foundations of the Basque press were laid in these two tens.

Final Line of 70

In October 1970, they celebrated the publication of the number 400 on Okendo Street. Juan San Martín, Martín Ugalde, Anjel Lertxundi, Gurutz Ansola, Edorta Kortadi, Mikel Ugalde or Gorka Knörr were some of the names that have been swept away so far. The end of Franco and Transition were the hardest times of Celestial Light and the most powerful journalism. Everything was in Basque society and the young journalists of the journal joined the fluidity and warmth of events, trying to homologate Basque journalism with that of neighbouring countries. After leaving the 40-year-old prison, Basque society began to shift the trends and ways of life of the democratic countries of Europe.

All round, but then, as 43 years later, the Basque press needed readers and Zeruko Argiak, Anaitasuna and Goiz Argi declared 1976 the Year of the Basque Press. That year he jumped from the newspaper format to the journal we know today, dedicating the front page to the Lemoiz nuclear power plant, which was widely rejected in Basque society. The hot topics were happening in the magazines, preparing at the same time the road to hell: in the spring of that same year, for the first time in colour photographs, he took the bruised body of Amparo Arango, torn apart by torture, and several months later filled the ikurrina, four months before its legalization. The magazine was in its peak, “people came to Okendo’s residence to buy the magazine,” says Elixabete Garmendia, director of the magazine and the finest chronicle of Zeruko Argia’s life of that time. In the last section of that writing of Celestial Light, women identified themselves: Garmendia herself, Pilar Iparragirre and Lurdes Auzmendi.

.jpg)

Decadence

These were glorious times for the journal, but since 1977 there has been a decline. On the right side of nationalism came Deia and Egin, and Zeruko Argia bled, both from journalists and from subscribers. Garmendia himself explains this: “Above all, many PNV militants were discharged for not agreeing with our radical and fighting edit line.”

The magazine had many collaborators. As colophants, Bixente Ameztoi, Antton Olariaga or Jon Zabaleta, for example; many people writing, among them, Joseba Sarrionandia, and also Koldo Izagirre and Ramón Saizarbitoria with the section “Baietz aste mal”. In that environment of decay, Baleren Bakaikoa brought Joxemari Ostolaza to the journal, and later Joxemi Zumalabe and Jon Barandiaran. The tension with the Capuchins, owners of the media until then increased and, stimulated by editorial discrepancies and debts, in 1980 the rupture occurred. In an interview on page 38 of this journal, Ostolaza himself tells in detail how everything lived.

Orena de ARGIA

.jpg)

In compliance with the condition imposed by the Capuchins, they had to remove the Sky from ARGIA. Ostolaza, Zumalabe and Barandiaran remained and soon another group of young people arrived, including Josu Landa, Pello Zubiria and Iñaki Uria. They were set up as cooperatives and gradually emerged from the disaster, consolidating a very important key to this day: The light-publishing company, regardless of its legal structure, would be available to workers from then on. Zeruko Argia could not be the name of the magazine, but it would become the name of the company that edited Argia until 1997.

Light experienced a very complicated situation in the early 1980s and had to pause for two months in 1982, which gradually abandoned, to the point of turning the initial volunteer group into workers. In this context, it emerged in 1982 as a support for the journal Argia Eguna. In the middle of the decade, the project rose again, keeping the weekly witness of the Basque press. In that decade the Anaitasuna fell and left its legacy in the hands of Argia.

As circumstances improved, the team took steps at the technological level and since then, in 1985, the computer company Apika was created, a precedent that would later be ASP. Two years later the printing press Tamayo has been purchased and with the name Antza has become the company that was created then. In the 1990s, Argia, ASP and Antza created the Ametzagaiña group, essential for the survival of the Light, without which the prolific trajectory in the world of technology and the Internet would be incomprehensible.

Newspaper in Basque

In the 1980s, the ARGIA working group launched three milestones. First, he took Argia out of the hole, gave dignity to the Basque press and demonstrated that it was viable outside of bilingualism; secondly, he created a business fabric that has guaranteed him to survive to this day; and thirdly, he put the starting point and the infrastructure to create Euskaldunon Egunkaria on 6 December 1990. The Basque Government’s subsidies to the press vasca.En were also opened in the 1920s,

Argia became a reality that Argia was unable to carry out, along with eleven more players from the Egunkaria sortzen platform. In 1930, it was Bilingual Day promoted by the Jeltzales who buried the newspaper’s project in Basque. In the case of Egunkaria, the PNV and the Basque Government presided over by him wanted to carry out a public project in Basque, but it did not go out and Egunkaria finally saw the light.

.jpg)

The literary magazine Susa, antecedent of the current editorial, and the thought magazine Larrun, today distributed as a complement to Argia, were founded in the prolific decade of Argia. And the first edition of the Argia Awards to be held on 25 January at the Atxega Restaurant in Usurbil was also held in 1989. The Argia Awards cannot be understood without mentioning the recently deceased Félix Sarasola. In addition, it made it easier for ARGIA to organize the prizes in the restaurants Txartela, Chespín Negro and Atxega.

At the same time, between 1987 and 1990 a large group of journalists were gathering to carry out the journal. Argia was done mainly in Donostia-San Sebastian, but in Bilbao a group also started to join, among others, Laura Mintegi, Antton Azkargorta and a group of students studying journalism in central Bilbao. A group of journalists from the first promotions of studies in Basque from the UPV/EHU landed on Ametzagaiña Street in the Donostiarra neighborhood of Egia to the writing of Argia that had made Mundaiz Bidea: Imanol Murua, Luistxo Fernández, the cousins Lorea Agirre, Sabin and Iñigo Makazaga, Joxe Angel Aldai, José Luis Aizpuru, Andrés Gostin or, among others, Xabier Letona. At the beginning of that decade, the local press was also created, with the Navarre magazine Ttipi Ttapa in 1981. The weekly Arrasate Press, created in 1988, would give the push and model to the local communicative explosion that broke out in the 1990s.

Deep crisis

.jpg)

But not all was gold, most of the Argia journalists and the company’s top cadres went to Egunkaria – the first director was Pello Zubiria and CEO Joxemi Zumalabe – and Argia bled to death. Garbiñe Ubeda – director, Pablo Sastre, Juan Joxe Petrikorena, Iñigo Makazaga and Xabier Letona remained in ARGIA. The reinforcements would soon come, among others, Josu Landa and Pello Zubiria, who had gone to Egunkaria, or Joxemari Irazusta, who was in charge of organizing the company as a manager. The crisis was at least three: economic, linked to the journalistic model, which for the first time Argia had to work with a newspaper in Euskera, and the business model.

As a result, Argia suffered the biggest attack in the mid-1990s that it suffered in the last 30 years. The closure of Susa magazine, coordinated by Gorka Izeta and led by Patxi Larrion in Larrun, was another milestone in the fight against male violence. There were also cuts in the working group. In 1997, the crisis had a major impact on Basque society, especially in the Basque sector. In his atrium, in 1994, Zeruko Argia SAL purchased the current Lasarte-Oria pavilion, which would be his first headquarters and would allow him to go on borrowing from the banks. On the contrary, Argia was unable to maintain open representation in Bilbao in the late 1980s; in Ipar Euskal Herria he has also had collaborators for the last 40 years and for the first time hired a journalist in Ipar Euskal Herria, Mikel Asurmendi.

ENAM long arms

From a human point of view, 1997 was a serious crisis, which greatly affected the drafting team and left deep wounds among the team members. In any case, the internal and external causes were confused in this crisis. The Basque National Liberation Movement (MLNV), the main centre of the organization of the Basque Left, had at that time an avant-garde trend and a great influence on many popular movements in the Basque Country. The exception was not clear and there were times of tension with the ENAM structures, both because of the cracks that were taking place in the rest of the Abertzale left as a result of the armed struggle, and because of the avant-garde nature of ENAM’s tendency to control the associations and institutions of the popular movement.

.jpg)

In 1997, for example, many leaders of Herri Batasuna denied talks to Argia – until “your internal problems were solved” – or personalities of the Basque culture and the Abertzale left concentrated in front of the Lasarte-Oria headquarters with a banner calling for “the situation to be resolved”. And worst of all, from the core of ENAM, messages were also issued not to buy Argia and unsubscribe from subscriptions, which caused significant damage to their subscriptions.

But from there, the majority of the working group also emerged and in order to deal with the crisis Zeruko Argia SAL was left behind and in 1998 Komunikazio Biziago SAL was created, which currently publishes the journal. The name chosen indicates a lot of the environment in which he was, since after the creation of Egunkaria, Argia struggled to find his place, and a stronger and more solid communication was essential. Light was reformed and since then everything was printed in color. Since that deep crisis, two values were reinforced that were already within his bosom: one, the possession of the worker, and the other, the independence of the project.

Available for Internet

In the months and years following the crisis, a new wave of journalists filled the editorial gap, including Onintza Irureta, Nagore Irazustabarrena, Eriz Zapirain or Estitxu Eizagirre. And at the center of the crisis, in the mid-1990s, the first echoes of the Internet began to be heard. Unlike most of the local media, the magazine saw the survival window and soon began to digitize its contents in the Luz en Red portal. In 1997, Argia published all interviews between 1963 and 1996 in a CD-ROM. In 1996 Ttipi Ttapa put the first contents of the press in Basque and in 1997 ARGIA did the same. Put it on the network and spread it, as through the Hari@ newsletter it soon began to send the news that it treated the 2,000 people subscribed to the service daily.

By the end of the century, Argia was already ready to maintain the digital revolution of the 21st century. As in the rest of the media, for years there has been debate about offering content in a free or remunerated way, and on more than one occasion Argia has been about to give the key to its contents, but in the end the option of offering them free of charge has always prevailed. The Basque in itself has quite a few obstacles in today’s society to put us more; therefore, before profitability – which is very doubtful even if the lock succeeds – Argia has preferred dissemination in the first two decades of the twenty-first century. The journal reaches its centenary with this vision: all contents are free and licensed CC by-sa, so that it can be enjoyed by whoever wants, provided that it disseminates them under the same conditions. In the opinion of the journal, this formula may have a great future to share and disseminate content among the Basque media as it had never before. It is a formula widely used in daily Internet content, incorporating news from other media of the same license to ARGIA.

Also web TV

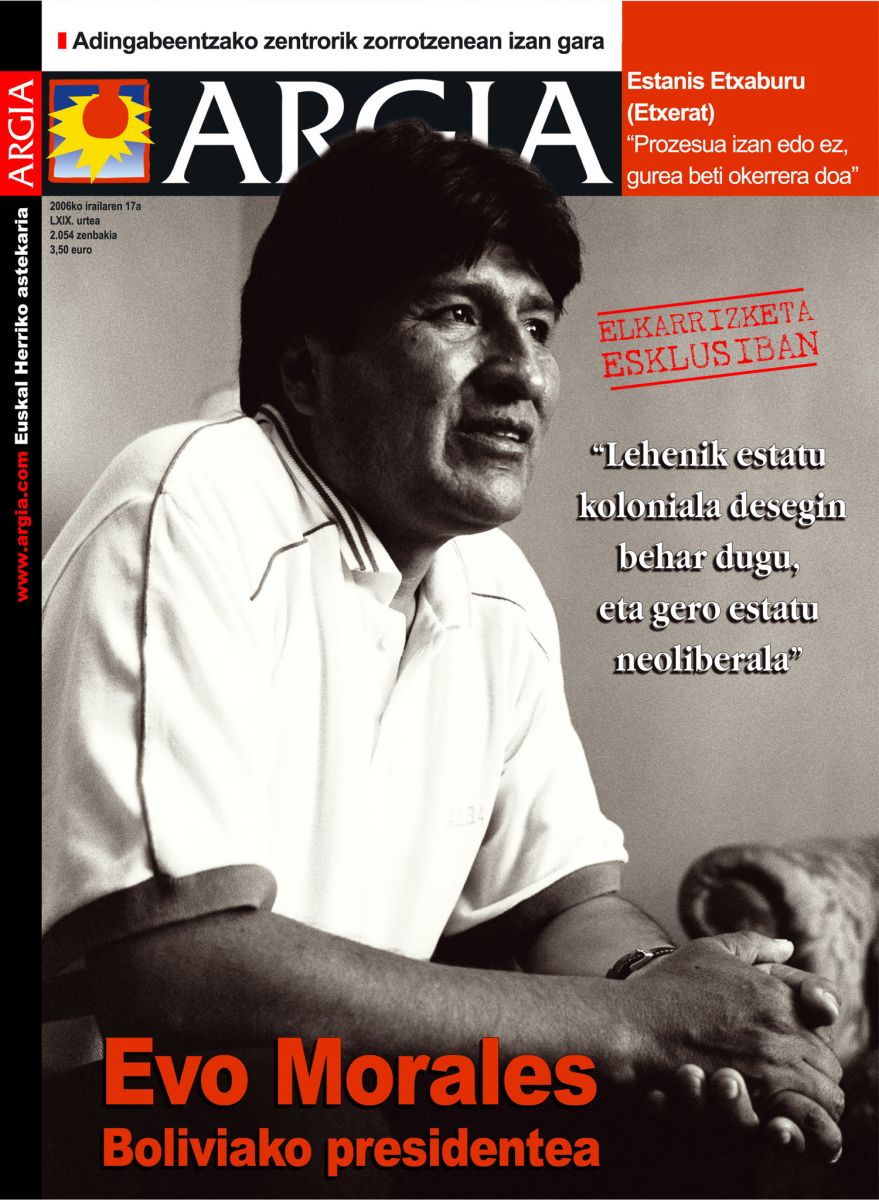

In the first decade of the 21st century, the process of transforming journals into multimedia media began entirely, not only through the integration of all written contents, but also through the production and dissemination of audio-visual, seeing that the Catalan Vilaweb did so. The first was an interview that the president of Bolivia, Evo Morales, interviewed in 2006 with AMETS Arzallus and Txomin Txueka. Then there was a great list, among which the bertsolarism session Hitzetik Hulera or the satirical Beranegi informative that achieved great success among the young. In the first decade of the 21st century, dozens of young journalists who landed in the writing of Argia were key to strengthening social networks, multimedia and journalistic content: These include Urko Apaolaza, Unai Brea, Jon Torner, Gorka Bereziartua, Mikel García, Lander Arbelaitz or Axier López.

In addition to multimedia, Argia has taken important steps in these two decades from the point of view of business diversification. He held the Temporapas Yearbook TXT, a company dedicated to digital technology and content Iametza Interaktiboa that is currently working on the creation of the Luditoys games company, along with other companies of Ametzagaina. In this context, the Bizi Baratzea project is also part of the project, which is being promoted by Jakoba Errekondo. It was also introduced into social networks from the very beginning and has been widely disseminated and influenced by Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, Telegram and Mastodon.

.jpg)

Distribution of powers and salaries

Looking outward, in recent years he has worked intensively on the creation and development of the Basque media association Hekimen. Small projects are currently being carried out with the Mbolo Moye Doole association of Bilbao, which brings together Senegalese migrants, or several book publications with ELA. He is also a member of the OlatuKoop Transformative Economy network. From the internal point of view, worker participation and labor democracy have been present in the identity signs of the last 40 years, but in the last five or six years has been dedicated to delving into these values and working horizontally, sharing power, responsibilities and wages in the most egalitarian way possible. Argia also maintains its attempt to strengthen territoriality. Proof of this is the fact that Amaia Lekunberri has been hired to bring news from Bizkaia.

There are many names mentioned in this report, those that do not mention that with this knower a lot of injustice is done, that in most cases do not work as journalists, and that are as essential as journalists for Argia to reach its centenary. Subscribers, readers, advertisers, workers, sponsoring companies, subsidies from Basque institutions… each of these elements has been fundamental for the survival of this project. Today, the Argia team continues to work independent journalism in Euskera, Euskal Herria, fully committed to Basque cultural and social transformation, working and claiming the free journalism that any democratic society needs.

"EITB euskalduna, zuzendaritzatik hasita!" lelopean, otsailaren 25ean egingo dute elkarretaratzea, asteartean, EITBko ELA, LAB eta ESK sindikatuek nahiz Aldatu Gidoia ekimenak deituta.

Vietnam, February 7, 1965. The U.S. Air Force first used napalma against the civilian population. It was not the first time that gelatinous gasoline was used. It began to be launched with bombs during World War II and, in Vietnam itself, it was used during the Indochina War in... [+]

Hirietako egunerokoa interesatzen zaio Sarah Babiker kazetariari; ez, ordea, postaletako irudia, baizik eta auzoetan, parkeetan, eskoletan, garatzen den bizitza; bertan dabilen jendea. Lurralde horretan kokatzen dira bere artikuluak, baita iaz argitaratu zituen bi lanak ere... [+]

The other day, as I was walking through the famous television series The Wire, there came a scene that reminded me of despair. There, the management of the newspaper The Baltimore Sun brought together the workers and alerted them to the changes that are coming, i.e. redundancies... [+]

.jpg)