Break, open or appear

- At the end of November, I attended a course on literary authorship. I can't make an objective chronicle and I've tried to make an honest chronicle. How is the playing field of Basque literatures and how do we move in it?

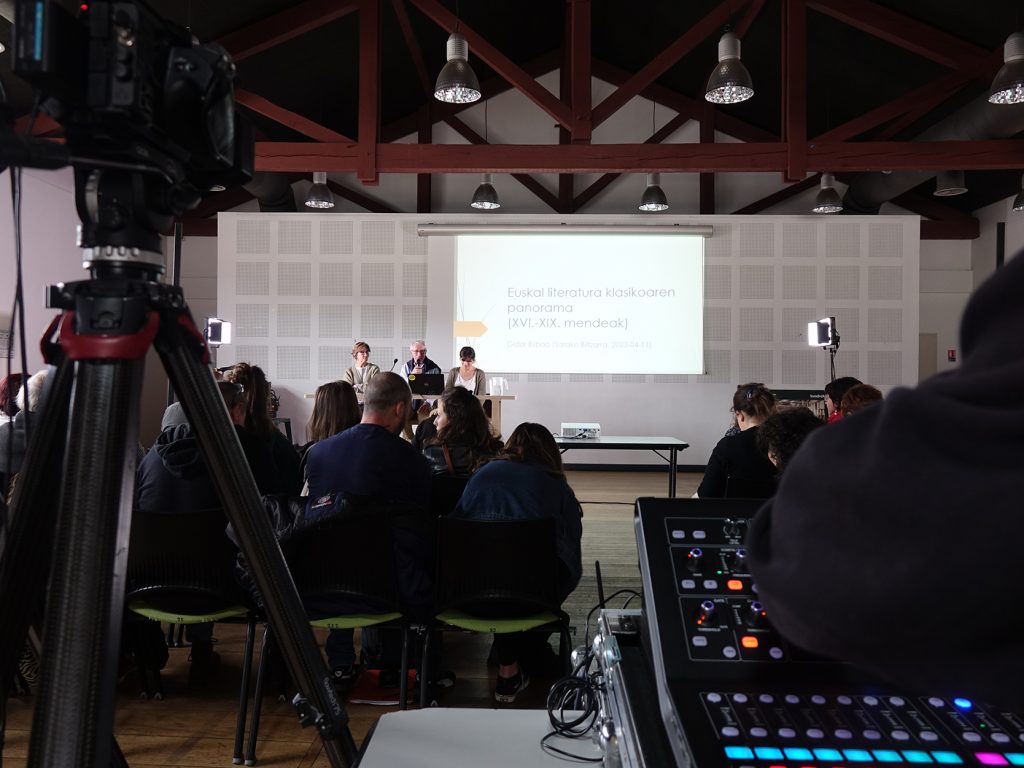

In winter there is also the Basque Summer University. On 23 and 24 November, for example, I went to a course in Eibar: “Ways to stage the activity: an approach from feminist literary criticism.” It was organized by Iratxe Retolaza and Amaia Serrano, a member of the Department of Literature of the UEU, and was prepared to continue with the string of another course. In fact, in July 2017 we met in the same place with the intention of talking about Basque literature and feminist literary criticism and in the assessment sheets many participants commented that they would like to go deeper into the subject. However, I myself.

Intentions and Intentions

I was so keen to attend this course, which coincided with my concerns over recent years, as I signed up as soon as I opened the registration period – I remember on 3 September. And not only that. I convinced the people of ARGIA that I would write the chronicle and they would post it. And I set out to gather it all together and order everything carefully and express it. And on the first day, on Friday afternoon, everything was quite normal, no surprises: a regular course, very interesting and no problems changing paper. But on the second day, something happened. Something had broken, opened or appeared. I don't know exactly what to say and I don't know exactly how to say, but at two o'clock at noon, when the course ended, we weren't like the day before when we got going. To the devil, therefore, with my projects as a discerning chronicler. I had no choice but to be a good chronicler.

What I can say objectively about the course

And what can a good chronicler do? First of all, please explain in detail what the two-day programmes were. To begin with, on the first day, Ibon Egaña offered a talk about the authorship and bodies of the authors. A historical review, some theoretical notes: the place that authorship has had in history and how visions and debates about it have changed, as the body remains warm 50 years after Roland Barthes gave it death.

Then, led by Retolaza, the workshop of texts in Basque that explain the authorship: Bizenta Mogel, Itxaro Borda, Ur Apalategi… An opportunity to see in flesh and bone the tendencies mentioned by Egaña.

The following day, first, Serrano analyzed a practical and paradigmatic case: Xabier Montoia (Elkar, 2008). The novel, a young sister of Marvels, refers to the sad and heartbreaking story of Josefina Lamberto, a very appropriate reading to talk about memory, testimonies and authorship. It must also be borne in mind that Montoia, for a long time, has not promoted his books in public: that is another way of putting his activity on the stage.

After Serrano, the turn of Eider Rodriguez: I have not said it well yet, but in the text workshop and in the talks we hear clearly that gender construction influences the way of presenting oneself to the plaza as author. And that's what Rodríguez has analyzed. In the spring and summer of this year he has conducted in-depth interviews with four writers: Arantxa URRETABIZKAIA, Laura Mintegi, Karmele Jaio and Uxue Alberdi. She asks them what it has meant for them to be women in the playing field of literature. The criteria for the selection of these four authors are from different times, they began to be published at different times, they come from different territories and all have children. In this first approach, Rodríguez has taken motherhood as a starting point.

In the testimonies collected by Rodríguez there were differences, nuances, but there were similarities; there are also experiences shared by the four writers, each in their own way. These patterns have been identified by Rodríguez and classified into groups, and presented them to us: among other things, writers have felt lonely; they have had a low perception of their position because the world has returned the same position; they have often accessed the playing field of literature by the hands of men; they have tried, in the aspect, to show themselves as neutral as possible to the plaza, with the fear that the credibility and legitimacy of their work will be impaired. The research will be read on paper next spring, within the Lisipe collection of the editorial Susa.

In conclusion, Garazi Arrula Ruiz (writer and translator), Uxue Alberdi Estibaritz (writer and bertsolari), Inazio Mujika Iraola (writer and editor) and Hedoi Etxarte (writer and bookstore) met around the roundtable on the experiences of authorship. They all answered Ibon Egaña’s questions and, in parentheses, I have placed them in a double trade, precisely because that was one of the conditions for them to be brought to the table: not only in the drafting, but in another area.

The female and male writers have lived in a very different way the activity and the plaza, and this is due to a system and a social organization and relations of power, and not to the void, the result of the idiosyncrasies of the individual author

Egaña asked them, among other things, when and how they became writers? Have you ever stopped being a writer? Did you show up as gender writers when you became authors? Who and how did gender mark and what weight did it have on your activity? Has it given you any advantage to be male authors? Do you think your voice has more legitimacy (it has had) than that of women? Does the author, creator, creator, who are you have body? What kind of body? Have you been aware of your body?

The diners, among others, talked about territoriality and linguistic option as a cause of feeling “small” in front of others. Alberdi, for her part, explained that yes, she appeared as a gender writer in the plaza of literature – and also in Bertsolarism –: “I was a 22-year-old. At the same time I went out to the square of Bertsolarism and to the world of letters.” In Alberdi's words, his gender was marked by dozens of journalists, photographers, other writers and a more adult man in the literary system who was persecuted at the age of 19. After this, Miguel Strogoff answered the question that touched Pugachov and summarized as follows: “What am I going to say after this?” Surely, the first step is listening.

The closing conference was offered by Harkaitz Cano, who developed his career as an author and commented on the doubts and concerns that currently arise in the face of the past.

In view of the gap; the way forward

And now, the hardest factory. What did it break in the course, or did it open or did it appear? What produced us, why weren't we the same before and after we started? Perhaps because it was clear, both in the testimonies collected by Rodríguez and in the round table itself and in the final speeches, that female and male writers have lived in a very different way the activity and the plaza, and that this is a result of a system and a social organization and power relations, and not in the void, the result of the idiosyncrasy of the individual author. In other words, patriarchy affects activity as much as capitalist logic. It seems the same as always, I know, repeated many times, and yet it brought something.

The organization of the course opted for mixed participation, that is, all genders had the opportunity to attend the sessions and both women and men took the floor. However, in order to determine what interests it, it has to be said that the participating women were much more numerous than the men. Despite the need for non-mixed spaces, mixed spaces have something to do with the rupture of the rock, with the opening of the gap, with the appearance of the abyss. The course broke something for everyone, opened, appeared, but being in different positions made it different, and we saw the difference. The female authors that we were there, the female authors that we are in different ways, we had already heard spoken out loud, confirmed, what we had just mentioned, and often, in our own friends. Men felt uncomfortable as usual, just as women felt uncomfortable in the public square. But in this area, it seems that they still have a critical reading of the privileges of masculinity.

Discomfort can be the starting point for giving birth to a series of theoretically known or considered principles, and it is now to be seen whether this discomfort will be fruitful, will generate more awareness and debate and change. I myself, in my humble judgment, am glad that something was broken, or that it was opened, or that it appeared. It was time and we needed it.

Now that everyone has become more Franciscan than the Pope, it’s worth remembering our unsurpassed classics. There was one in the 17th century, his grace was Arnaut Oienart. And since we can’t immerse ourselves in all his works, today we will praise O.ten youth in... [+]

Aurreko tertuliako galderari erantzuteko beste modu bat izan zitekeen, akaso modu inplizituago batean, bigarren solasaldi honetako izenburua. Figura literarioaz gaindi, pertsonaia zalantzan jartzeko, edo, kontrara, pertsonaiaren testuingurua ulertzeko saiakera bat. Santi... [+]

Astelehen honetan hasita, astebetez, Jon Miranderen obra izango dute aztergai: besteren artean, Mirande nor zen argitzeaz eta errepasatzeaz gain, bere figurarekin zer egin hausnartuko dute, polemikoak baitira bere hainbat adierazpen eta testu.

Martxoaren 17an hasi eta hila bukatu bitartean, Literatura Plazara jaialdia egingo da Oiartzunen. Hirugarren urtez antolatu du egitasmoa 1545 argitaletxeak, bigarrenez bi asteko formatuan. "Literaturak plaza hartzea nahi dugu, partekatzen dugun zaletasuna ageri-agerian... [+]

1984an ‘Bizitza Nola Badoan’ lehen poema liburua (Maiatz) argitaratu zuenetik hainbat poema-liburu, narrazio eta eleberri argitaratu ditu Itxaro Borda idazleak. 2024an argitaratu zuen azken lana, ‘Itzalen tektonika’ (SUSA), eta egunero zutabea idazten du... [+]