- The fashion of running up the mountain? They see nothing."

- This woman, who suffered the hardest reprisals of war and dictatorship, claims to be communist, atheist and anticlerical. He worked as a smuggler and a limiter. He has had time to walk on the mountain and, although he has turned 90 years old, he usually goes weekly to the mountain.

1936ko Gerraren bortizkeria ezagutu zuen txikitan: Gernikako bonbardaketa, aitaren fusilamendua, amaren atxiloketa eta familiaren mespretxua. Kontrabandoan eta jendeari muga zeharkatzen lagunduz atera zuen bizimodua gaztetan. Mendizaletasunaren aitzindarietako bat da Nafarroan, Angel Oloron senarra zenarekin batera. 91 urte ditu eta jarraitzen du igandero mendira ateratzen. Duela ia 50 urte Nafarroa Kirol Elkarteko mendizaleek eraiki zuten Belaguako aterpea berriz zabalik ikustea espero du ilusio handiz. Irailaren hasieran aterpe berriaren lehen harria jarri zuen.

What was your childhood like?

The mother was from Pamplona, teacher. In Pamplona, teachers who were not Carlists did not have a place and therefore had to leave. It started in the village of Ardatz, in the Egüés Valley, and then in Marcilla. There he met my father, who was originally from Villafranca. In 1923 they married and went to live in Pasaia. He was proposed to appear on the Popular Front's lists for the 1936 elections, and he accepted the proposal. She was told that there was a Carlist priest who offered things to women in exchange for her vote and that among them there were many acquaintances of her mother, so they proposed to introduce her to get those vows. The news had a great echo, as everyone knew the village teacher. The Popular Front won votes and many did not forgive our mother.

Immediately after the war, the father went ahead to fight for the republic. I saw the hammer and sickle in his uniform, so I think it was communist.

Then my mother and I went to Bilbao, specifically to Erandio, to a humble house of workers who left us, with another family. My brother was already in Pamplona. In 1934, he was destined to study escorts and lived with his grandmother, his mother's mother. It was a carlist. Grandpa, on the other hand, was not a carlist. He was from a brown town, a quadrilateral. It was he who built the stone palisade surrounding the hospital.

Did you witness the bombings in Bilbao?

Yes. My mother saw both of them, but I only saw Gernika. My mother would go to the villages to get food and take me to the Lutxana Tunnel to be sheltered with other children and women, while she was out. That's why he saw the bombing of Durango. He said it was harder than Gernika's, but it didn't have any boxes.

In Gernika's he came home from a scare and there he found us the boys and girls betting where the bombs of the planes would fall, as if it were a game.

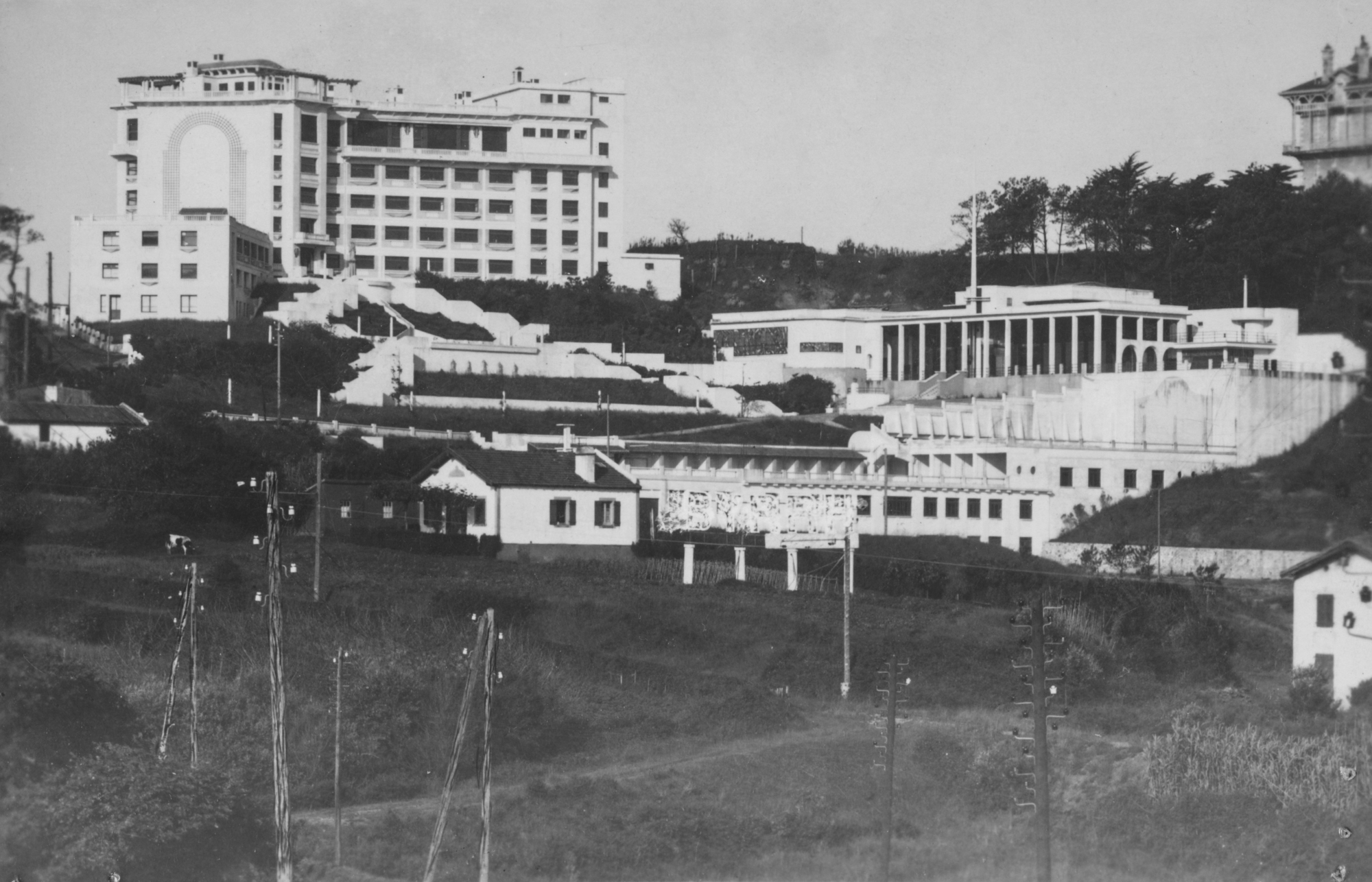

You see yourself trapped in the middle of the Battle of Santander. What was it like?

After the bombings the fascists were getting closer and closer and we went to Santander. The situation was also appalling. We arrived in August. We saw the fire bombs coming out of the planes. They looked like flares. When they were filled, people would go into the sea on their own, desperate, trying to run away in any old wooden boat. Patriots made themselves available to their people to withdraw the boats, but not to Republicans. The father and other militiamen were surrendered. The Carlists told them they would stay quiet, send them home the next day. “I will come home before you. By the time you arrive, I will be by the fire, preparing the porrusalda,” he told us. It was the last day I saw my father. Instead of home he was transferred to the concentration camp of Trujillo in Cáceres and shot on December 27, 1937.

How did you experience your father's shooting and your mother's arrest?

The letter came to her mother telling her that they had shot her father, but we have not yet found her remains. The following year, in 1938, the mother was arrested. He knew they would come and search for him and went to live outside the village. Nobody helped us. Nobody in the Bretos family welcomed me. Most of them live in Donostia and Pasaia, and recently I've gone to say goodbye and challenge them for what they did to us. Most of them are oppusies and nuns.

Less well than a former president of Emakume Abertzale Batza who was a refugee in Pasaia welcomed me into her house. I was with him until my mother was arrested. I remember perfectly well that she fired from my mother believing that they were going to fuse her. I had the phone of Matías Anoz, the owner of the well-known hostel Casa Martzeliano, because I was a friend of my parents. Immediately after she called her, she went to look for me to take her to the grandmother. Two years later, in 1940, the mother left prison and moved to Pamplona.

How did they get through?

It was very hard. Eight days after my mother arrived, the grandmother kicked us out of her house. He was not his brother, but he had given him the opportunity to stay with him. We had nothing, but from the first day we had the help of the Abertzales. Before his mother's arrest, the editorial Aranzadi gave him work and the day after his arrival in Pamplona he was assigned a job in the laboratory that had the Azketa family. In the same building there was a grocery store, the woman of a Falangist. The man moved to Madrid with a position and left his wife and five children, all of them male. Because that woman didn't know how to hold accounts, my mother helped her make the rationing cards and the store. One day a friend of his father appeared in the store in Oiartzun and Beñardo Erreka, from Quinto Real, who lived in Kanbo. He was the head of the resistance in that area. They proposed to their mother to sell smuggling stuff in that store.

Once a week, they brought him the packages and gave them the money he had sold. So we started smuggling. We sold chips, saccharin, thermometers… and bracelets with the symbol ‘zazpiak bat’.

We also brought red tobacco from Pasaia. The first time I was about 12 years old, and I put in a big coat a bunch of tobacco on the train. However, I didn't have much fear.

Did you help people cross the border?

When I was very young, I started crossing the border with people. And then quite the opposite. I didn't know their names, I didn't know anything. They slept in the Casa Marceliano and when the inhabitants came to the fair to sell their things, they came out of the inn, mingled among the people and went to Madrid to catch the freight trains.

They were combined jobs. I was going by bus to Eugenio. I slept in the last village house, and the next day, at four o'clock in the morning, a forest guard named Errea threw some stones at me in the window. Then I got up and walked with him to Urepel, 20 kilometers walk. When they arrived, they told me who I had to help to Pamplona. They were usually women of resistance. When they were too afraid, I slept with them. Many times we wore clothes. Some of the girls here were powerfully married to their boyfriends in Mexico and we took them to Urepel to take their things by bus to Baiona. There they picked up the plane and headed for Mexico.

Ideologically, how do you define yourself?

I am communist and anticlerical. And I atheist like my mother. I go to church, but I don't think so. What I think is that we have to do well here. We were previously fooled by heaven and hell, but what is that for today's young people, for those who know everything? I'm not Abertzale. I brought the ikurrina everywhere until the death of Franco, which was the symbol of the struggle against Franco. However, the Navarros nationalists were not like those of the Basque Country and they helped us a great deal. The Navarros were of Basque Nationalist Action, and they had the Carlists against, while the others were right-wing and still are today. The nationalists agreed with the Italians not to bomb the blast furnaces in Bilbao and get the nationalists in Santoña out on the boats. They brought out the nationalists, but not the Republicans. They remain the same, making deals with the right, but the ones here are very different. Those here helped enormously, for example, the left-wing prisoners who fled Ezkaba prison.

When did you start going to the mountain?

When I was young, I started hiking with other boys and girls in 1948 or 1949. On Sundays we went on buses organized by the Sports Society Navarra (Club Deportivo Navarra). At first, they were not allowed to go to the border mountains. We started to approach Orhi in the 1950s, for example, but you couldn't take photos.

How did you meet Ángel Oloro?

On the mountain, of course, and on the mainland. In the past, we women could not enter the village bars. Once in Lekunberri they took a porch with soda beer, but I don't like it. I wanted water and Angel took me a container from the bar. Then he and other friends would come home and search for me on Sundays to join the bus, because we would normally leave very early.

What has the mountain given you?

And what gives me! Everything. The relationship with nature, sounds, animals, clean air… Angel also loved nature. I wouldn't let or take flowers. Today I continue to go to the mountain with Joaquín Salbotx and other mountain companions. We will travel 8-10 kilometers on the mountain every Sunday.

How do you see the current mountaineering?

What do you say? The fashion of running up the mountain? They see nothing. I wouldn't do it even if I was 18! The same is true of those who go by helicopter to the eight-thousand mountains.

But there's a lot of hobby, right?

Yes, but now people go otherwise to the mountain to see if they make three mountains the same day and so on. Before, in Tolosa and Vitoria-Gasteiz, the hobby for sport was very special. Now less. The old ones have grown old and the young people prefer to go to the Himalayas. They don't want to go to the mountains here.

Have you, in addition to the Pyrenees, walked through other high mountains?

Yes. In the year I turned 50, we went to Mont Blanc. A friend took a little ikurrina and put it on the top. We walked through Italy and Switzerland with a R6 that I was driving.

What is the most beautiful mountain you've ever seen?

Vignemale and Neouvielle are the most beautiful, but I all like them. Mount Ezkaba, for example, I love it. Midi is also a spectacular mountain. I had a lot of materials that the Americans had left me since the time of smuggling, including a tent weighing 20 kilos. We went to Midi for the first time. While the others set up the store, I prepared the dinner: potato puree and solomillo.

On 1 September you were putting the first stone of the restored hostel Angel Oloron de Belagua. What has been that refuge in your life?

It has always been very important. The project began in 1968. At first they had to do it down, but they were told that the road would pass through and they looked for a new location. The project was launched with a loan requested by the Club Deportivo Navarro and opened in 1971. It's been closed for 13 years and it's been a shame. Angel was appalled to see him in free fall and didn't want to go there in recent years. Aid has now come from Europe to rebuild the shelter, but on condition that this special aspect of the tent is maintained. They are working at a good pace and enlargement is expected to take place next year. It makes me a tremendous illusion.

Paquita Bretosek Carmen kaleko bere etxean hartu gaitu. Kafe goxoa eta bezperan egindako bizkotxoa atera digu hamaiketakorako. Sobratu dena bi puskatan jarri eta aluminiozko paperean bilduta eman digu Dani eta bioi etxera eramateko. Argazki albumak atera dizkigu eta hitz eta pitz kontatu digu nola joaten zen mendira bere gona-prakarekin eta amerikarrek ekarritako zapata berezi batzuekin.

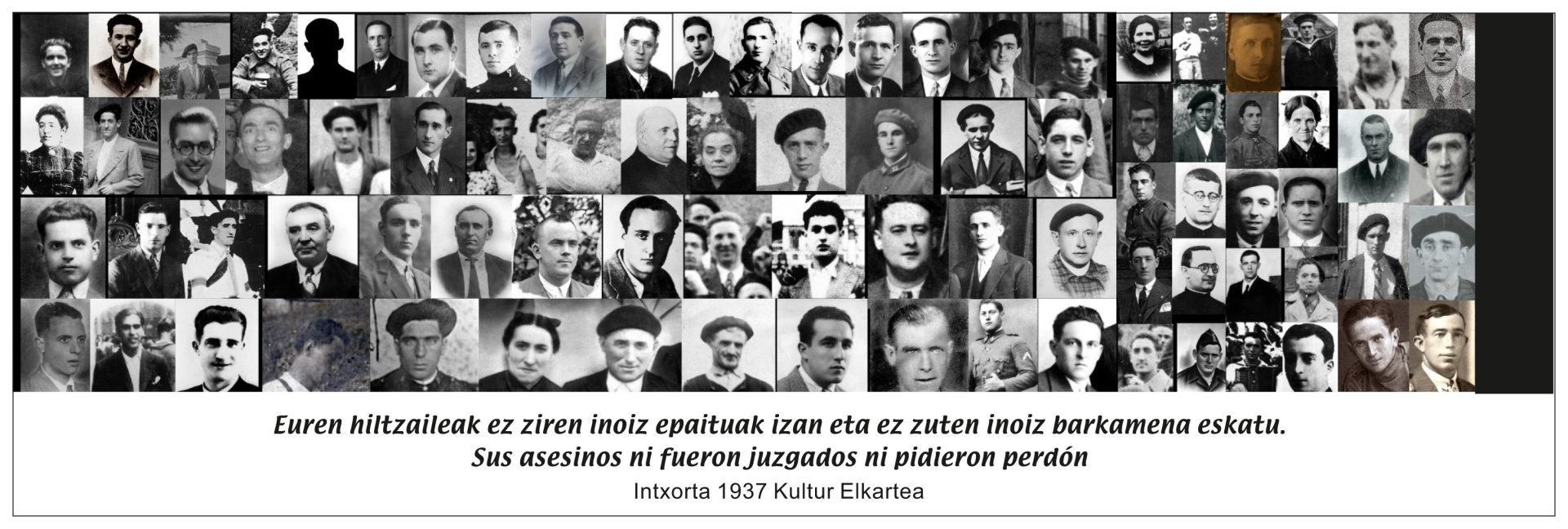

Pamplona, 1939. At the beginning of the year, the bullring in the city was used as a concentration camp by the Francoists. It was officially capable of 3,000 prisoners of war, at a time when there was no front in Navarre, so those locked up there should be regarded as prisoners... [+]

Segundo Hernandez preso anarkistaren senide Lander Garciak hunkituta hitz egin du, Ezkabatik ihes egindako gasteiztarraren gorpuzkinak jasotzerako orduan. Nafarroako Gobernuak egindako urratsa eskertuta, hamarkada luzetan pairatutako isiltasuna salatu du ekitaldian.