Changing the church to destroy the regime

- In November 1968 some 60 priests occupied the seminary of Derio and were closed for almost a month, denouncing the complicity of the Catholic hierarchy with the Franco regime and demanding the radical change of the Church. In the 1960s, these cures became the catalysts of many people and tired movements of repression and, aware of the need to give a stronger response, they created the “Sendoa” group. At a time when the pulpitas still had great power, their total activism was very important to start destroying the regime. But they paid dearly.

Josu Barandica (Bermeo, 1939) knew perfectly all the secrets of that giant building, as he studied there for 13 years. On 5 November, therefore, he entered the seminar in Derio without any problems, driving a second-hand quadribus, although by then all the surrounding areas had been occupied by the police.

They came directly from San Juan de Luz, from the press conference that accompanied the four winds the lockdown begun the day before by the Abades, with Juan Mari Arrangi and Angel Zelaieta. Through Telesforo Monzón, The Times, Le Monde, Reuters and other international media gathered at the Angelu abbey of Piarres Xarriton to address the issue. “The issue was very serious, we held a full seminar, and that press conference was our strongest speaker,” Barandica said after 50 years.

The imprisonment of dozens of Biscayan priests who remained for twenty-five days at the Derio seminary since 4 November 1968 was not an isolated event, but another eye of the chain of concern that existed within the church of the Basque Country among the young priests and seminarians. The young people who witnessed and experienced the oppression of Franco, not only denounced the close link between the ecclesiastical hierarchy and the regime, but also claimed a Church that was not “subject to the intention and life of capitalism”, called the Basque Working People.

It is wrong to believe that this is a remote history, because, as now, it was more about changing the system than about religion and faith, than about changing the same system that is now in force.

With the action of Derio they wanted to obtain the intervention of the Vatican, and although they did not, they ended the lockdown convinced that the appointment of the Basque bishop José María Cirarda as apostolic administrator of Bizkaia would bring with it some change. But the few hopes soon faded: jail, exile, torture, fines -- they continued to be the bread of every day.

Parishes as a refuge against Franco

From the very moment when the Francoist “crusade” began in 1936, the Spanish Catholic Church found dissidents within itself. Do not forget the Basque priests shot by golfers, some of them, such as José Aristimuño Olaso Aitzol, who were tortured to the point of distorting the face in Ondarreta prison. For his part, the bishop of Vitoria-Gasteiz, Mateo Múgica, died locked and blind in the Zarautz desert, after his conscience forced him not to support the uprising.

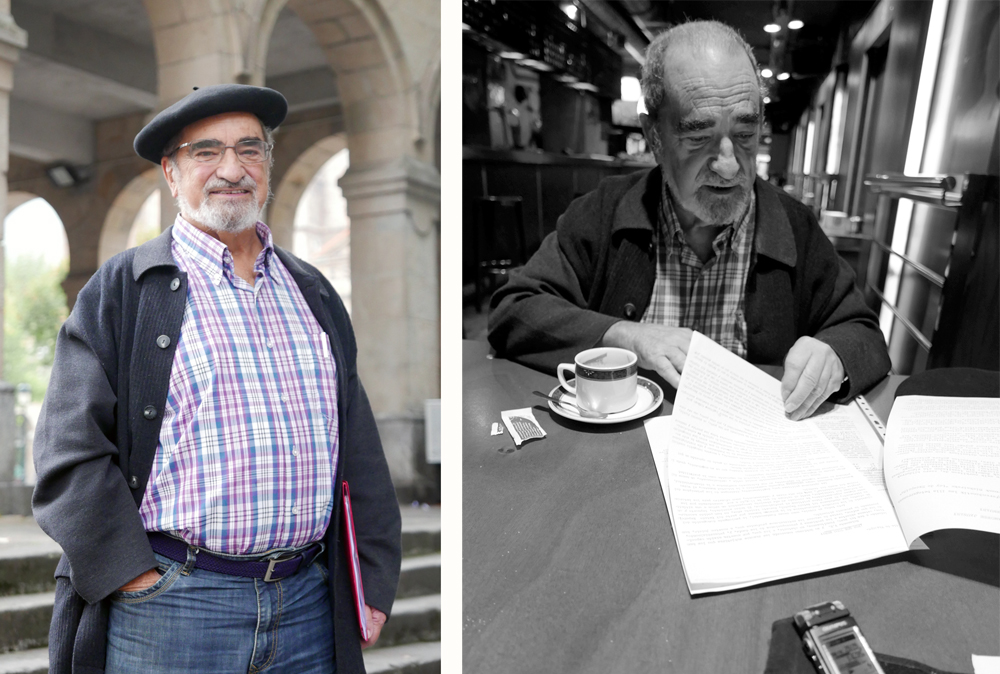

Josu Barandika:

“If something was going on in the long term, we couldn’t get into a cathedral, we needed a bed building, lounges -- and we knew it well. But above all, the seminary was a big resonance box.

The letter of the 339 Basque abades, signed in 1960, once again showed Basque dissent. ETA was born two years earlier, and both abbeys and convents became a refuge from the clandestine struggle. Through groups such as Herri Gaztedi, cultural activities were promoted in the villages. In Orozko, for example, in the parish of La Barandica, social preparatory courses were organized.

Why did they get into those cases? The question has an easy answer for the former abbot: “We use our own bells.” The Church was very strong among the citizens, but at the same time it was subjected to dictatorship, and they took advantage of this contradiction to unite the people: persecuted, with difficulties to survive, workers… “In our sermons we talked about rights”.

One of these sermons was fined by Juan Mari Arrangi (Durango, 1941) for preaching against torture and detention. Ordered at the age of 25, he began his ecclesiastical career in the mining areas of Ortuella and witnessed the situation and political repression of his workers: “The first reaction was to denounce by sermons and writings, but the ecclesiastical hierarchy remained complicit in the regime.”

After the false referendum in 1966, a group of priests and religious sent an open letter to Franco, in Spanish and Basque, in the face of the emergency situation first established in Bizkaia:

“For you and your government will have reason to take this decision, because we cannot stay without casting our cry of grief and rejecting ourselves, when we see the facts that have been pronounced and the shameful situation in our country.”

“But the words were not enough,” says Arrangi, “it was time to move on to the facts.”

Indarra Group

Among the priests there were a number of opinions among those who said that it was necessary to act more harshly and those who did not see anything clear. The House of Spiritual Exercises in Begoña became the epicenter of debates and programs. Those who were in higher ecclesiastical responsibilities accused the most committed priests of “making politics”, precisely they resorted to the political organization imposed since the war.

They met at the Abades Coordinator to start preparing the activities – the name “Borroka” began to be used shortly before Derio’s lockdown, under the slogan “Against Hardness”. The first coup d ' état occurred in 1967: The Gran Vía de Bilbao was filled with demonstrators with a fountain that joined the workers of the Etxebarri Strip Mill factory, who carried a long strike.

That's how 1968 came. The year Marthing Luther King was killed. And Txabi Etxebarrieta. Paris. Prague. Vietnam. Junta de Arantzazu and Zamora prison. Meliton Manzanas. Son of Itziar. Conclusions of the fifth assembly. The creation of different fronts within ETA will mean, in Barandica’s words, that the organization “is incorporated into the themes of the people”, which will have a great influence in the coming years.

During the months of July and August 1968, a group of priests will hold two enclosures in the offices of the Bishopric of Bilbao, including the prohibition of funeral masses in favor of Etxebarrieta to demand the rejection of the order of the Civil Governor. The answer is the same and we can read it in a letter that is kept in the archive of the Benedictine in Lazkao: “It serves as a scandal to the faithful, and as an offense to the Church and the Homeland”

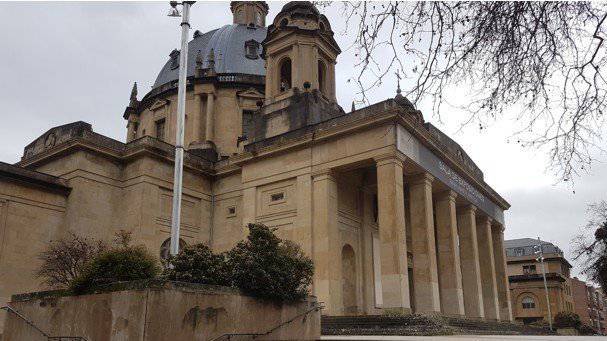

Derio: “Four, four, thousand”

4 November, at 4 p.m., and a thousand pesetas in the pocket for maintenance expenses. Four, four, thousand. This was the slogan to go to the court of Derio's seminary. Tired of the eternal answers, the priests planned this action with the intention of doing something stronger. But why Derio? “If something was going on in the long term, we couldn’t get into a cathedral,” Barandica says, “we needed a building like this: beds, rooms… and it was a place we knew well, that was important. But above all, the seminar would be a big resonance box.”

.jpg)

The lockdown had not been thought of from the next day until the next day. They had previously worked well on their message in an extensive report. The skeleton was the work of Luis Mari Laibarra, abbot of the Urigoiti district of Orozko. Laibarra lived in the same house as Barandica: “He built the document, wrote it and then commented it at night.”

The final touches were carried out in the house of Periko Berrioategortua of Amorebieta, and one rainy day on the eve of the lockdown left the report at the train station to be taken to Rome by Martín Olazar and Juan Mari Arrangi. “We tried to reach Pope Paul VI through senior religious leaders related to Euskal Herria, but there was no official response,” says Arrangi.

Shortly afterwards, the abate Martin Orbe tried in vain to do the same. And a year later, when the police arrested him in connection with the operation of the Bilbao Corridor, they made him pay his daring [see Article 25]. “You cannot be subjected to torture for a lifetime,” he recently acknowledged with ARGIA (No. 2,613) During the interview.

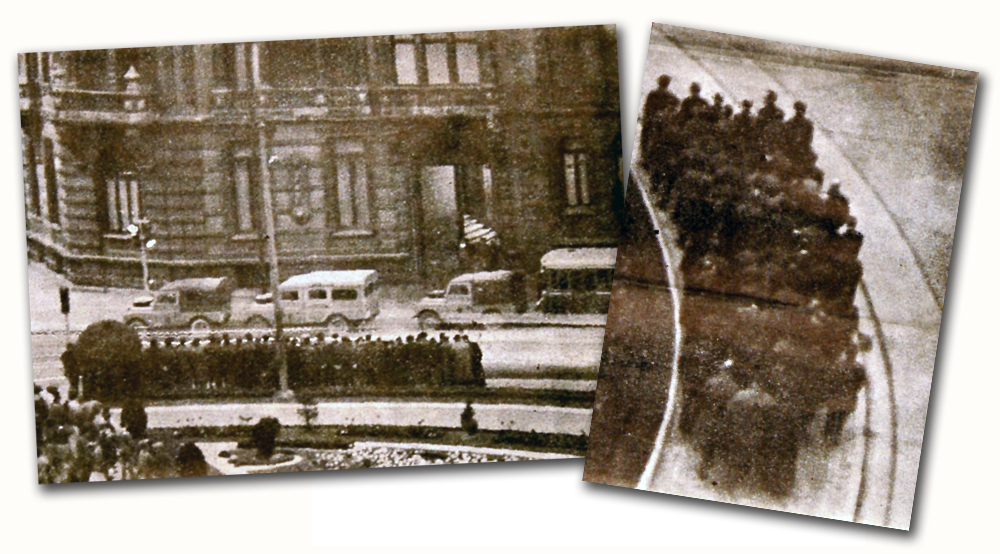

As soon as they crossed the door of Derio’s seminary, the priests became part of a harsh political scenario. Eight SEAT 1500, three jeep and two National Police buses. The agents tried to get in. Seminarians and teachers in front of them. Punishment for divinis and Sundays without mass in many towns. Solidarity of the Catalan abades: “Amb the situation in which the Poble Basc is stubborn.”

While the Spanish press called them rebel priests or problematic priests, the international press accurately explained the reasons for the action.

It is wrong to think that this is a remote story, which, as it is now, was already about changing the system, rather than religion and faith.

Among the priests, a group was formed to spread the confinement, another to talk to the parish priest and another to organize meals. The owner of the bar Cantábrico of Bilbao, which later opened the Taberna de Iñaki, prepared meals for the okupas of the seminary: “I think Iñaki did almost everything for free,” says Barandica with a thank you smile. There were many anonymous people who helped financially this action.

When the night fell, under the shelter of the night, those who were locked up in the seminary went to the people to explain their reasons. The rooms were filled with people. That was not a strike, it was to go directly against the Church: they wanted to lead their task by a “defeated” people.

After the death of sick bishop Pablo Gurorder and the inauguration of Cirarda as bishop of Bilbao, the priests left the seminary a few days later. Why? In the last issue of the newsletters that were drafted during those weeks, the following was explained:

“As far as we’ve asked, don’t forget, but we’ve decided to do it. (…) We intend to move outside, until we get our heads together with our Erriaga and for the sake of our country.”

“The Church changed us”

The priests finished the occupation with the commitment to collaborate with the popular movements. Many resigned from the state’s salary, sought civil work and participated in trade union or political organizations; they also continued the protests, such as the hunger strike of a group of priests in May 1969. “We wanted to change the Church and he changed us,” says Juan Mari Arrangi.

Arrests, torture, sentences of several years in the special prison of priests in Zamora, exile... The compromise reached put many abades at the centre of repression and in practice the Indarra group was dismantled. But they left the Borroka disk for memory.

Jose María Cirarda gotzaina (Bakio 1917, Bilbo 2008) pertsonalki ezagutu nuen Derioko seminarioko okupazioan. Gotzain horrek okupazioan izan zuen papera nabarmendu nahi nuke, itxialdian zeuden abadeen bi bozeramaileetako bat izanik –bata euskaraz eta bestea gaztelaniaz– berarekin jardun bainintzen.

Geroztik ez nintzen inoiz gehiago berarekin egon, baina pentsatzen dut ez zituela sekula nire hitzak ahaztu, are gehiago irakurrita askoz geroago, 1996ko azaroan, bere “azken konfesio pertsonala”. Erbestean nintzenean, hilzorian zegoen gure aita bisitatzera joan zen 1971n Basurtoko ospitalera, eta hori ere bada beste arrazoi bat lehen esan dudana pentsatzeko.

Gogoan dut Derioko seminarioko okupazioaren azken egunetako batean Cirardari esan niona. Itxialdiari amaiera emateko asmotan etorri zen, Pablo Gurpide otsagabitarra gaixotasunak jota hil zenean administradore apostoliko izendatu baitzuten.

.jpg)

Seminarioko areto batean geunden bilduta abade guztiak Cirarda monsinorea agertu zenean. Saiatu zen okupazioa utz genezala konbentzitzen, eta orduan hitza eskatu nuen. Isiltasun handi bat egin zen eta zera esan nion: “Gotzain jauna, gure herriak jasaten duen errepresioa, atxiloketak eta tortura salatzeagatik Jesukristo bezala gurutzera igotzeko prest bazaude, euskal herritarren eta pertsona gizatiarraren eskubideak defendatzeko prest, ziur egon gu guztiok zure atzetik joango garela, zurekin. Baina Elizaren ohiko isiltasun konplizea mantentzen baduzu, borrokan eta salatzen jarraituko zaitugu”.

Agian nire lotsagabekeria eta ahotsaren indarrak harrituta, Cirarda begira jarri zitzaidan adi entzunez. Baina ez zuen ezer esan. Hilabete gutxi batzuk geroago bai, etorri zen erantzuna. Ez zegoen prest gurutzera igotzeko, ez baitzen ausartu 1969ko maiatza arte atxilotutako ehunka pertsona laikok jasandako torturak salatzera, ezta bere abadeek jasandakoak ere. 1969ko apirilean errepresio gogorra izan zen, batez ere Bizkaian eta abadeok ere kolpatu gintuen. Batzuk atxilotuak izan ziren eta haietako gehienak Zamorako konkordatu-kartzelan giltzapetu zituzten. Beste batzuk, nire kasuan bezala, Frantziako Estaturantz egin ahal izan genuen, erbestera.

Abade horietako bat, Martin Orbe, modu basatian torturatu zuten. “Beldarra”, “paseilloa”, “kirofanoa”… Denetarik egin zioten. Cirarda espetxera joan zen Orbe ikustera. Honek torturaren arrastoak erakutsi nahi izan zizkion eta prakak jaisten hasi zen, baina gotzainak esan zion ez halakorik egiteko, berak esandakoa sinesten zuela. “Nola ez dut nire abade bat sinetsiko?”, esan zion.

Agian nire lotsagabekeria eta ahotsaren indarraz harrituta, Cirarda begira jarri zitzaidan adi entzunez. Baina ez zuen ezer esan. Hilabete batzuk geroago bai, etorri zen erantzuna: ez zegoen prest gurutzera igotzeko

Hilabetea igaro ondoren, Cirardak eta Jacinto Argaya Donostiako gotzainak –honek ere Jon Etxabe bere abadeetako batek jasandako torturen lekukotza bazuen– pastoral bateratua zabaldu zuten: “Datua [torturarena] objektiboa balitz, autoritate agente batzuen partetik biolazio injustuak egin direla esan nahiko luke. Asmaturiko edo nahita puztutako datua balitz, ordea, autoritatearen kontrako propagandan biolentzia injustu bat egongo litzateke. Ez da erraza egia zehatza jakitea, batzuek baieztatu eta besteek ukatu egiten baitute, eta gertakari horien izaeraren ondorioz ere sekretuak indar handia baitauka…”.

Bere memorietan, Cirarda jauna saiatzen da idatzi hori justifikatzen: “Ez zen koldarkeria izan. Tortura horien frogak ez izateak geldiarazi gintuen”.

Ez, Cirarda monsinorea, ez zenituen arrasto edo froga horiek ikusi nahi izan, ezta konpromisorik hartu ere, ez zinelako inoiz gurutzera igotzeko prest egon!

Juan Mari Arregi

Melaminazko mahaien egur iluna hautsak hartuta dago Kili-kili aldizkariaren Bilboko Goienkaleko erredakzio zaharrean. Armairu baten barruan, alanbre oxidatuz itxitako 40x40 cm inguruko kaxatan sartuta aurkitu dugu altxorra: Gogor diskoak.

Duela 50 urte Derioko seminarioko itxialdia egin zuten abadeek grabatu zuten diskoa, borroka luze hark iraun bitartean abesten zituzten doinuekin. Baionako Agorila zigiluak argitaratua –2012 CDan berrargitaratu zuen–, frankismoaren kontrako erresistentziaren ikur bilakatu zen berehala.

Baina zer egiten zuten diskoaren binilozko 700 ale baino gehiagok Kili-kili-ren egoitzako armairuan gordeta? Aldizkariaren sortzaileaz pare bat berba egin behar historia hau ulertzeko.

.jpg)

Jose Antonio Retolazaren magnetofoia

Jose Antonio Retolazak (Bilbo, 1929-2014) txikitan galdu zuen euskara, baina bere kabuz berreskuratu zuen, Gasteizko seminarioan. “Eliza eta euskara izan ziren beti bere bidea”, dio Etxahun Galparsoro haren suhi eta Lazkaoko Beneditarren artxiboko teknikariak. Hala, 1959an Arrazolan abade zebilela, berak antolatu zuen lehen aldiz meza euskaraz, eta 60ko hamarkadan Kili-kili pertsonaia sortu zuen Bilboko San Anton elizako katekesiaren babespean, haurrak euskaraz alfabetizatzeko, gerora komiki aldizkari ezagun bihurtuko zena.

Retolazak elizaren hierarkiaren kontra joatea hautatu zuen, eta 1960an Francoren kontrako 339 abadeen gutuna sinatu zuen. Hala “hondatu” zuen eliz karrera, bere lagun kutun Juan Uriartek ez bezala: “Firmatu izan baleust gaur ez zan gotzain izango”, dio autobiografia liburuan oraindik Donostiako gotzain emeritu denaz.

1968an Derioko okupazioa gertatu zenean, on Klaudio Gallastegi San Antongo abade ezaguna seminarioraino eraman ohi zuen Retolazak autoan, itxialdian zeudenei meza emateko. Eta berekin batera Grundig magnetofoi handi bat ere bai. Dirudienez, makina horretan jaso zituen abade errebeldeen lehen abestiak.

“Baina diskoa ez zen seminarioan grabatu”, argitu digu ziur Xabier Amurizak (Etxano, 1941). Derioko borrokaren inguruan testigantza bat uzteko helburuz sortu zen diskoaren ideia, behin itxialdia amaituta: “Pentsatu genuen bildu behar zela talde bat kantatzeko esperientzia genuenon artean, 20 edo 25 izango ginen, eta grabazioa Zornotzako karmeldarren komentuan egin zen”.

Camarade-curé

Atzean mezu politikoa zuten euskarazko kanta liturgikoak jaso zituzten, baita bertso sorta ezagunak –edo Amurizak itxialdiaz egindakoak– eta bogan zeuden abestiak ere, Julen Lekuonaren Ez, ez dut nahi ospetsua adibidez.

[Bilduma osoa hemen entzun daiteke]

Hain justu, azkeneko doinu honen gainean ahotsa jarri zuen Colette Magny kantari ezkertiar frantziarrak, handik bi urtera diskoa bere eskuetara iritsi zenean. “Apez laguna, zigortu zaituzte / Baina zure zigorra herriak beregain hartu du eta jujatu / Izendatua den apez berriak ez du nehor izanen mezan”, dio Camarade-curé abestiak frantsesez. Orain, kanta horren genealogia eta euskal abadeen historia oinarri hartuta, dokumentala estreinatuko du Pierre Prouveze zinegileak.

Itzul gaitezen 1968ra. Behin grabazioa eginda, haren masterra Ipar Euskal Herrira eraman zuten Amuriza eta Retolazak, azkeneko honen mini-morrisean, eta haiekin on Klaudio: “Errespetua sor zezakeen norbait behar genuen muga pasatzeko eta abade hura, bere 150 kilo eta sotanarekin, pertsona egokiena zen”, gogoratzen du Amurizak. Jendarmeek alto emanagatik lortu zuten kopia hura Telesforo Monzonen eskuetan uztea.

Xabier Amuriza:

“Pentsatu genuen bildu behar zela talde bat kantatzeko esperientzia genuenon artean, 20 edo 25 izango ginen, eta grabazioa Zornotzako karmeldarren komentuan egin zen”

Amuriza eta Derioko beste abade asko jadanik Zamorako kartzelan zirela ikusi zuen argia Gogor diskoak 1969ko maiatza inguruan. Erabat klandestinoki zabaldua eta guztiz jazarria izan arren –poliziak haren atzetik ibili ziren etxe partikularrak eta baita Euskaltzaindiako egoitza miatuz ere– oihartzun handia izan zuen. Ez zen meza soil bat, zapalduta zegoen herri baten garrasia baizik.

ARGIAk zabalduko ditu

Urte askoren ondoren, Julian Goikoetxea izeneko lagun bat hurbildu zitzaion Iñaki Egurrolari kalean. Egurrola Euskerazaleak elkartekoa izanik –Kili-kili hasieratik babestu zuena–, esan zion bazuela beraiena zen gauza bat. Burdina lantzeko Basauriko tailer batean, pisu handia zuen mahaia ezkutuko palanka batez mugitu zitekeela deskubritu zuten eta haren atzean zulo bat: han zeuden 12 hatz-beteko LP biniloak. Halaxe eraman zituzten Kili-kili-ren egoitzara.

Berrogeita hamar urteren ondoren, frankismoaren errepresioaren ondorioz egiteke geratu zen lana amaituko du ARGIAk, eta disko horiek zabalduko ditugu gure komunitateko kideen artean. Durangoko Azokako standean izango dira eskuragai, baita gure webgunean ere (azoka.argia.eus).

Gogora Institutuak 1936ko Gerrako biktimen inguruan egindako txostenean "erreketeak, falangistak, Kondor Legioko hegazkinlari alemaniar naziak eta faxista italiarrak" ageri direla salatu du Intxorta 1937 elkarteak, eta izen horiek kentzeko eskatu du. Maria Jesus San Jose... [+]

Familiak eskatu bezala, aurten Angel oroitzeko ekitaldia lore-eskaintza txiki bat izan da, Martin Azpilikueta kalean oroitarazten duen plakaren ondoan. 21 urte geroago, Angel jada biktima-estatus ofizialarekin gogoratzen dute.

Bilbo Hari Gorria dinamikarekin ekarriko ditu gurera azken 150 urteetako Bilboko efemerideak Etxebarrieta Memoria Elkarteak. Iker Egiraun kideak xehetasunak eskaini dizkigu.

33/2013 Foru Legeari Xedapen gehigarri bat gehitu zaio datozen aldaketak gauzatu ahal izateko, eta horren bidez ahalbidetzen da “erregimen frankistaren garaipenaren gorespenezkoak gertatzen diren zati sinbolikoak erretiratzea eta kupularen barnealdeko margolanak... [+]

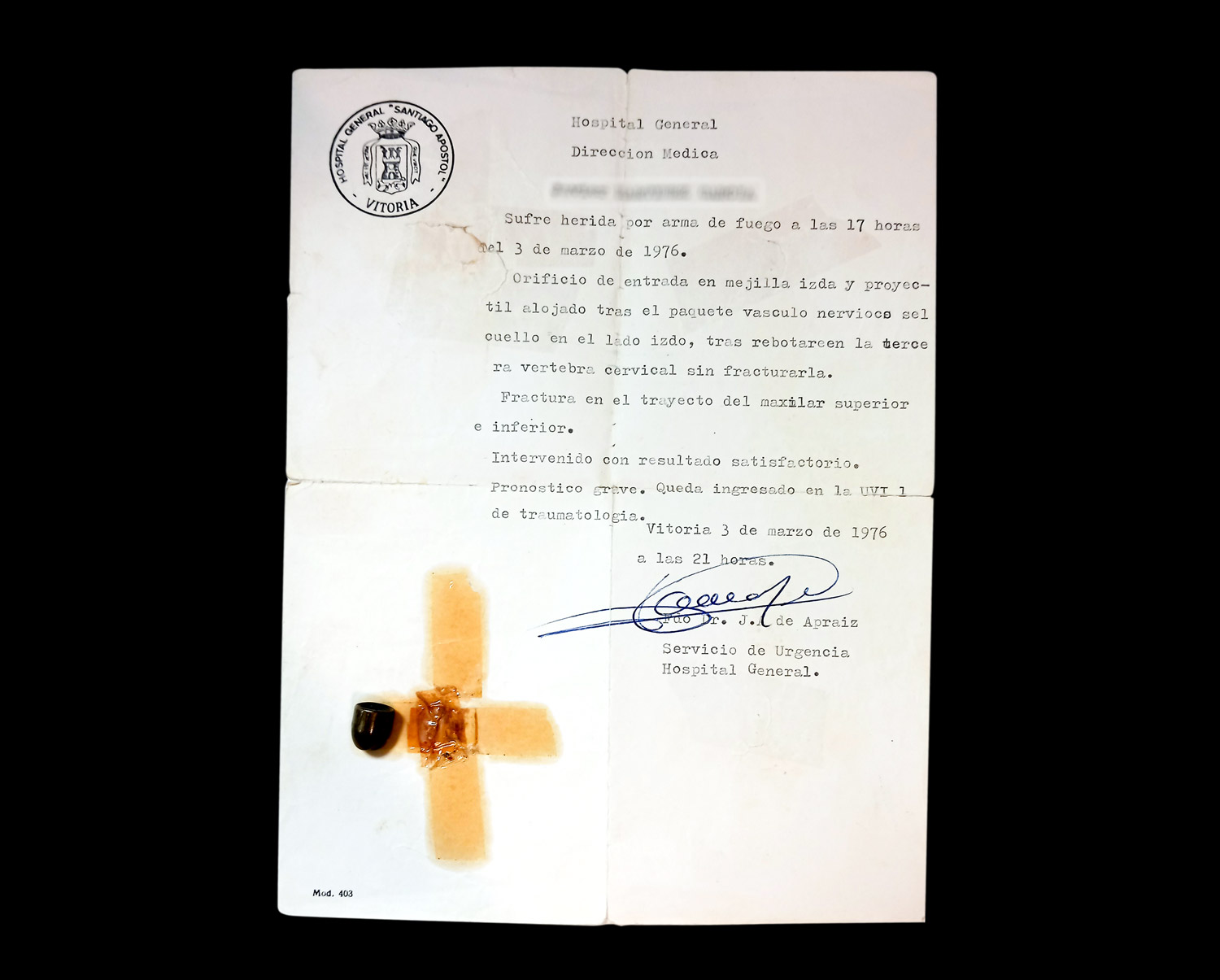

1976ko martxoaren 3an, Gasteizen, Poliziak ehunka tiro egin zituen asanbladan bildutako jendetzaren aurka, zabalduz eta erradikalizatuz zihoan greba mugimendua odoletan ito nahian. Bost langile hil zituzten, baina “egun hartan hildakoak gehiago ez izatea ia miraria... [+]

Memoria eta Bizikidetzako, Kanpo Ekintzako eta Euskarako Departamentuko Memoriaren Nafarroako Institutuak "Maistrak eta maisu errepresaliatuak Nafarroan (1936-1976)" hezkuntza-webgunea aurkeztu du.