Chevron-Ecuador: Private judges dominate the state in this way

- The American oil company Chevron was sentenced in 2012 by the courts of Ecuador to the payment of 8,100 million euros for pollution in the Amazon. A private court now acting as arbitrator in trade disputes has rejected this resolution in the Netherlands and has unpunished the damage suffered by thousands of citizens over the years. Those deprived of the Chamber of Commerce above the judges of the arbitral tribunals: this is how the impunity of the multinationals is organised.

The news has been spread around the world by the Union of Affected by Texaco with document #ChevronCulpable #NoMasImpunity: “On 7 September 2018, we heard the decision of the Hague Arbitration Tribunal, created under the Pact for the Promotion and Protection of Investments between the United States and Ecuador in 1993, condemned by Ecuador in 2007). The Arbitration Tribunal’s ruling is in favour of the multinational Chevron and its subsidiary Texaco and argues that the Ecuadorian judges have failed to comply with the obligations imposed by the investment pact.”

This is very important news that will set the precedent throughout the world and also in the rich North-West, in many conflicts between the population and the multinationals. Journalist Olivier Petitjean Multinationales.org summed it up in the observatory with the following title: “Contamination: A private international court has removed an historic fine against the oil company Chevron.”

The historical fine was EUR 8.100 million, imposed on the multinational Chevron in 2012 to repair the damage caused in the Amazon by an Ecuadorian court, later ratified by the Supreme Court. It was the largest fine imposed on a company for environmental damage in its history.

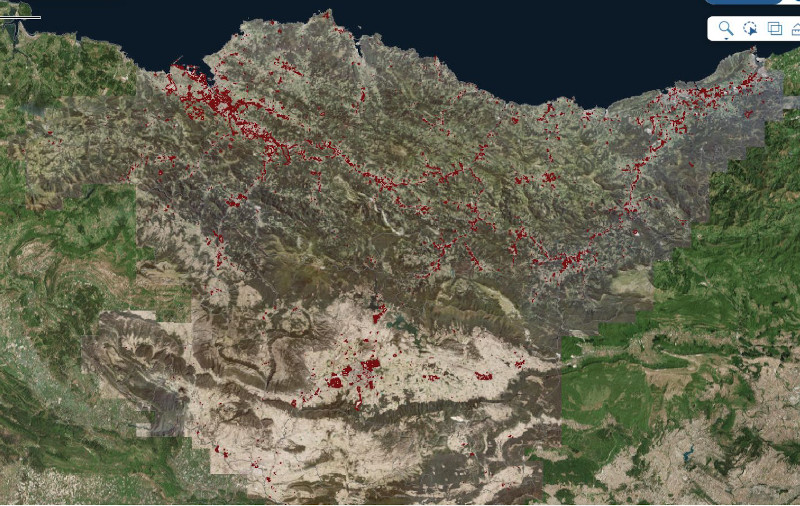

More than 30,000 residents of the Ecuadorian province of Sucumbios sued Texaco Petroleum, acquired in 2001 by Chevron, the second oil tanker of EE.UU, for dumping everywhere the remains of over 350 wells excavated to exploit the black gold of the Amazon, without any control and seriously polluting people as the nature of the environment.

Texaco managed oil production between 1964 and 1990 on an extensive area of more than one million hectares allowed by Ecuador as a concession. From the oil search holes, technicians deposited lubricants and products of all kinds that were used as extracted contagious sludge in the surveys, leaving uncovered the holes that had been dug during the search.

The Basque Government’s Environmental Justice Atlas has acknowledged that the company has over 60,000 million litres of toxic waste in its vicinity, plus 650,000 barrels of crude oil scattered around the site. The consequences have been fatal for the inhabitants of the area.

In this region there are large quantities of cancer, respiratory problems, blood circulation and reproductive problems, not to mention poisonings caused by consumption or consumption of contaminated chemical emissions from the oil industry. Because of the poisons, some localities have become empty: Tetetes, to Sansahu... They have also escaped from Cofanes, Sionas, Siekopai and many other peoples. Many farmers have been abandoned by pollution without fertile land, their cattle have died and men, like animals, are condemned to live by drinking contaminated water.

You can see on the Internet a shocking video – Chevron’s videos – showing the pride of oil exploiters and the lack of protection for their poor farmers. These are images recorded by Chevron's technicians and then some worker has anonymously communicated to local entrepreneurs. The company sent technicians to collect samples of uncontaminated land to be brought before the court as proof of the company and the video shows that they could not find clean land. The images show technicians demonstrating the immense toxicity of the soil. Several witnesses are also heard explaining their situations to the technicians, including a peasant who has lost three small daughters for contagion.

Goliath also has an arbitrator

Pablo Fajardo came to this region at the age of 14 and has scars from the oil industry on his skin. Born in a very poor, mestizo family, he managed to progress in school and access the career of lawyer at university, working day by day and learning at night. He is recognized as the leader of the forces facing Chevron and his citizens. In 2004, his brother was killed to, according to many, put his feet on Paul.

“Unlike many others with similar problems,” Fajardo told Petitjeani in 2015, we have decided that the fight will take place from within, using the resources of the courts. But 21 years later we have the feeling that the system is not done to do justice to the victims of multinationals like Chevron.” David had guessed Goliath what he was coping with.

A commercial court in The Hague has broken down what the courts in Ecuador agreed in 2012 and made it public. It is appropriate not to be lost in the forest of solemn words. Although based in The Dutch Hague, the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) has nothing to do with the International Court of The Hague or any other ordinary court. The PCA acts as an arbitrator in conflicts between states and investors. The courts of justice, composed of three professionals, are composed of states and companies and, when they do not agree, are designated by the World Bank, one of the main institutions that has designed and organized neoliberal globalization.

The president of the jury of referees between small Ecuador and giant Chevron was the president of the V Republic of Ecuador. 5. Member of the Stockholm Chamber of Commerce and the Institute for International Business Laws (ICC). The second is Horacio Grigera, director of the International Trade Arbitration Centre (CICA). And the third is English Vaughan Lowe, a member of several international arbitration organizations.

Three arbitrators have decided, as stated in the resolution, that the Ecuadorian court is corrupt, that Chevron is innocent of the accusations against him and that the Ecuadorian State must pay the cost of the cause and the compensation now allocated to Chevron.

The minimum is that the multinational in 2012 preferred to be tried in Ecuador rather than in the United States. A good law firm can remedy bigger mistakes than that. The most important thing is that a private court has misled the citizens who had so actively obtained something from the public courts, and another that says Multinationals: “This decision unreservedly confirms the primacy of business law over national courts, which the private courts of corporations send over national judges.”

Learn the new Legal Code governing the world: Investor-state dispute settlement. Arbitration of conflicts between investors and states. In Euskal Herria, we will also have to try.

.jpg)

.jpg)