Koldo Almandoz: "Always making the same film is very reactionary."

- The Donostian filmmaker Koldo Almandoz has a broad trajectory. Now, for the first time, the challenge has been to make a more convincing film(more). Oreina is the result of that attempt. He will compete in the New Directors section at the San Sebastian Film Festival and will be premiered in theaters on September 28. We talk to him as we train across the locations of the film.

The quote is from the Euskotren Station of Easo in Donostia-San Sebastián. The talks in the Tabernacle have their charm, but today we speak with the passage of the mole, the metro or whatever. From Donostia to Orio and back. We go through the geography of Oreina. You can see it's September, there aren't that many people anymore. Without looking hard, we've found a place to sit and chat peacefully.

Many protagonists and stories cross in Oreina. Where did he throw into what we can see today?

In Aginaga there is a very special house, half very well cared for and the other half with a disaster. I was interested. Who will live there? I remembered the family tensions in all the houses and from there one of the threads has emerged. Then I've combined it with another idea that I wanted to get into the movie: that we spend a lot of time on the move, alone, and that then we are more than ever ourselves. With the secrets that we can't count on anyone and with everything that we carry inside.

The locations have a prominent role. Through the surroundings of Aginaga, Usurbil and the Oria River, the city and nature that are usually very separated, you show both at once.

“In film we give too much importance to emotion n.Todo has

to be to create an emotion, everything is valued according to the ability to cry or laugh”

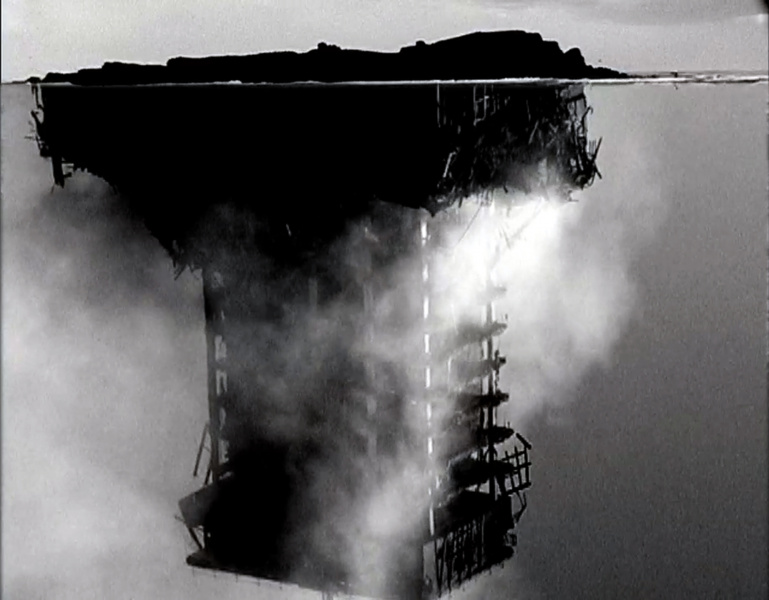

We have made an effort to touch the locations as little as possible. At first I looked at that landscape from the road, and what I saw from there caught my attention. I've traveled two or three times by the train, like today, to see how different the two sides of the river are. In one there are villages, industrial sites and urban life, while in the other part it is totally wild. There is no way in some sections. This has led me to reflect on the special periphery we have in the Basque Country. We find a periphery where nature and industries, dwellings and polygons come together. This generates interesting confusion, also among people, and I wanted to reflect that reality. That's the geography or the universe of the movie.

The diversity of the site also explains the diversity of the characters: a young Sahrawi, a forest ranger, two brothers from Aginaga who have taken two different paths, a young woman who works at her father’s gas station…

When I wrote the script, I started with an intuition of that kind, but then when we did the recording, we found a similar reality. We saw, for example, that there is a large Sahrawi and Maghreb community in Usurbil. We've talked about the people who live in those locations, because the ecosystem seemed really interesting to me. It is very current that it moves away from the prejudices that we normally have, both those that we have with the rural world and those that we have with immigrants.

The threads of these characters cross, but there are also ellipses that don't have a round closure. Is Oreina a job that requires effort for the viewer?

I believe that I owe respect to the viewer and that he has the ability to fill those gaps. We appear at one point in the life of these characters and disappear into another, but those lives continue. My bet has been to talk about people who don't normally show up in movies, normal people. They have complex personalities and different faces, as we all have. There's no Great, there's nothing very extraordinary. Not even the things that happened to them could be unthinkable. I think in film, we attach too much importance to emotion. That everything has to be to create an emotion, that everything is valued according to the ability to cry or laugh. For what makes me want to cry the most are the realitys of television. I wanted to make a film against this overvaluation and trend. There are emotions, but they appear as we live them in our lives, without underlining.

I'm struck by the character of one of them. It represents an archetype that is repeated a lot in the last Basque films: a man who does not know how to manage emotions, who defends himself in his coldness instead of resolving conflicts, dry…

It is true that this is reflected in the films that have been made lately, but I think it responds to a reality. It may be a matter of generation, but I look at my family, I look at my parents, and I think it's still the case. In part, when I look at myself, I feel identified with that. Imagine that the other brother of that character, though otherwise, is very similar. And all the other characters as well. They live looking deep inside.

Among the actors who have brought these characters to life is Ramon Agirre, one of the most renowned. You've worked with him before, and this year he'll be awarded the Zinemira Prize as a recognition of your career.

What happens to us with Ramón and others is that they're so close that we don't value them enough. It seems to us that they are our actors, but Ramón has worked with Almodóvar, Haneke… And if he has done it is because he has passed the casting, he cannot do it anybody else. There are actors and actresses that we're going to miss, and Ramón is going to be one of them. It's an impressive technique. In a sequence, to repeat things, said fourteen times, it will always breathe at the same time. My concern was not to see Ramón, but the character. That's why we've tried to look for an interpretation and a voice not to highlight too much, to make Ramón Agirre disappear and to see Martin. I believe that we have achieved this.

In contrast, he's met with an inexperienced actor in the world of comedy. Khalil embodies Laulad Ahmed Saleh.

“You’re no one

until you make a feature film for a lot of people. Now I've become a film director.

But I don’t care much, the truth.”

Yes, but it was necessary. It was clear from the outset that we would join the actors and those who were not, because it is also a way to give credibility and to work. In this case, the natural imperfection of those who are not has infected the professional actors, and the others have learned a lot by working with the professionals. I am very happy with Laulad’s work. In addition, in many cases we have not selected the phrases that are best, but the parts with imperfections. That gives it credibility. When we speak, we do not pronounce it perfectly, we do weird gestures… In cinema we tend to perfection and it seems that it is a written rule, but we have tried to get it out of there. Laulad offered it to us.

We've heard you say the recording process has to be open. Has it been so now?

When you make a movie of this kind, you need a script in which you really believe, but nevertheless, the process always has to change something. Otherwise it makes no sense to make the film, better to leave the script written. We, for example, have been greatly affected by the localization process or the work with the actors. You think a dialogue is round and when you see that in the actors' mouths you realize that it doesn't work, that it doesn't work, that you haven't written well. Then the animals have appeared suddenly, or we have taken some very nice images that we could not imagine when walking with the boat…

Has it been difficult to make these dialogues credible?

The decision I made at the beginning was not to abuse it, and what it is to do naturally, both as regards the selected Basque and as regards the mix of Basque and Spanish. Our linguistic reality is by itself complex. We have one reality in Donostia, another in Ataun… and the linguistic styles of the actors are also very different. We have tried to make it credible by pushing the actors to introduce the nuances of their Basque. It’s been curious, for example…

[We arrived at Orio and got off the train. We interrupted the conversation a little bit. In less than three minutes the train will arrive back. Almost without time to talk about other issues, we went back to Easo Square in Donostia].

I've forgotten what you were talking about... Languages?

Yeah, that's it. It was curious what happened to us with Khalil. She is Basque, both the actress and the character, but when we address a person of this kind we do not think she knows how to speak in Basque. That's what's reflected in the movie, but the other day we went to do an interview, and that's what happened to the journalist. The film has also served to emphasise these kinds of things.

You've spent the first time on the lands of a fictional feature film. It's a very different job than Sipo Phantasma or Plagan. People

usually expect what you've done before in your jobs, but I, on the contrary, feel the need to break with that. For me, it was a challenge to do something I hadn't done before, and I wanted to show myself that I had the ability to make a conventional movie. We have an obsession with authorship, with the idea of our own gaze… It seems to me a very conservative, retrograde attitude. I am not the same person as five or ten years ago, and it is normal that I do not do the same kind of work. We've all drunk different things, we all copy what we like, and you also have to notice those changes. Woody Allen's, for example, is already a constant self-plagiarism. I am not interested in that.

Even though you've done a lot of other jobs before, many have considered you a filmmaker now. In fact, Oreina will participate in the “New Directors” section of the Festival.

For a lot of people, you're no one until you make a feature film, that's right. Now I've become a film director. But I don't care much, the truth. It is true that it has a certain social prestige, but everything is cardboard stone. You don't need a special talent to be a film director, and the more I know a film director, the clearer I'm going to be.

You're critical of producers who live far away from creators. Did working with Txintxua Films make it easier?

Yes, I am very clear that I am a privileged one. Txintxua allows me to do things that would otherwise be very difficult. If I have the opportunity to make this film, it is by the producer Marian Fernández. He also pushed me to write the script. The wager, given the characteristics of this film, was not easy. Even when I have had moments of doubt, he has given me the push to move on. That said, it is true that that other aspect of film is also a bit wrong: financing, festivals, international sale, distribution… That influences a lot on the dissemination of your film, and often influences variables outside the cinema.

Does unconventional cinema have a place at the game table with those rules?

It's not easy. There's a new generation. Aitor Gamentxo, Maddi Barber, María Elorza, Maider Fernández, Juan Palacios… All of them have become accustomed to forms of work similar to those we had in Sipo Phantasma. Can they continue making movies without selling themselves? Probably not. It would be nice if they were also to push the way they are doing, but I see no commitment to that either on the part of the institutions or on the part of ETB. It's not a movie that gives Goya and pictures. It's not that one is good or the other is bad. We would need both.

Have you had to sell yourself?

“We should

overcome the tendency of filmmakers to despise the general public”

At least in part. Not so much in the work I have done, but in the relationships you have to have, where you have to be, what you can say and what not… The game of hypocrisy is also there. We all have a revolutionary speech, but then you look at some elites and you like to be there. In my case, when I started there were not so many people doing the same thing, and because of that I have been recognized by a people, I have made a way…

Recognition of the vanguard and applause of the general public. It is not easy to combine both.

It's still wrong to say it, but I make movies especially for me. With that hope of seeing the public, but for me. In this case, we have not made test or similar visits either. A movie is not a choice. No movie, no music, no general creation. Having said that, I think we should overcome the tendency for filmmakers to despise the general public. We live comfortable in the underground, we feed ourselves in a small world. We must also be able to get it out of there. We would like the general public to be interested in new or more dangerous things, but we, too, should make an effort to make this work please us and bring that audience closer. Those on the extremes are not going to be satisfied, but I've made a deliberate attempt to do something in between. This film will have the opportunity to be in the movie theaters, and the people who go will see that different proposals can be made. That there are different types of movies, different ways to do…

Now Oreina will make her way. But after you walk this more conventional path, what are you interested in?

I write, but I don't have any specific plans. Now I don't have a steady job, because of course, filmmakers don't live in film. So I am right now with a sense of disorientation. It is curious, sometimes I get scared and others make me feel at ease.

[The train arrives back to San Sebastian. We went out into the street, among the rest of the travelers. As we took photos, Almandoz confesses to us the secret of getting it right: some sunglasses. The three of us have left the station behind and we have installed on a terrace of Easo Square, with a gardo in your hand. It was supposed that then the most interesting conversation started. No recorder.

It's not the norm that an animation documentary is awarded with the public's prize. But Another day of Life is also not an animation work to use. Firstly, because part of the great war journalist Ryszard Kapuściński, from whom the book and the words are inspired A more vivid... [+]

Without making much noise, Isaki Lacuesta has already won two Golden Shells at the San Sebastian Film Festival in this decade. The first one seemed rather controversial, as in 2011 he brought to the Official Section The Steps, a rather ambitious work, with rather exaggerated... [+]