Journal of the Ghetto Centres

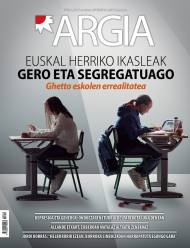

- The tendency to concentrate low-income students in certain centers is increasing in the Basque Country, and the data show this. In other words, the poor, many of them gypsies and migrants, are concentrated in extraordinary schools, with the consequences that this has for them and for the rest. What is the reality of these centers, what are their daily needs, demands and joys?

“It’s a difficult school, yes, but I don’t want to go to any other school,” says Miguel de Cervantes College Director of Vitoria, Juanan García. Miguel de Cervantes has 350 students, 90% receive a scholarship and the number of families served by social services is very high. And it's a difficult school, for example, because the mobility of students is very great: it's common for new students to start the course or for students to leave school, for example because parents have had to change from home, from neighborhood, from town, to economy, and that influences the education of the student and the rhythm of the group.

“There is also the affective factor there,” García stressed, as there are those who have emotional gaps. Because the burden some students carry on their backs is not small: “They tell you what has happened to you, or what your parents have suffered and think, what has happened is here every day, at school, and that’s a lot,” says Professor Ima Ortega. She works at Angel Ganivet School in Vitoria-Gasteiz and most of her 700-800 students live in families with scarce financial resources. “There are children who cry in June because they go on holiday,” he tells us. Many of them continue to work during the entire holiday period of the child and children have little leisure opportunities.” “To us,” García adds, one student once told us that he didn’t want the holidays because on vacation he had belly pain.” I mean, because I was hungry, because at school time they can eat free thanks to scholarships.

What is a bookmark?

The socioeconomic and cultural level of the parents also influences the academic trajectory. “The other day, in the Elementary School classroom (boys and girls from 6 to 7 years old) we started reading by making a bookmark,” explains Ortega. All of a sudden I realized that half of the class didn't know what the bookmark was. Why? Because at home, they don't have books. Then we will do the same diagnostic test to all the students of Euskal Herria, but the situation is not comparable.”

Imanol Martínez gives us another perspective: “Our experience is that what conditions the student’s situation is not so much the socioeconomic situation, but the attitude of parents towards school and learning. We have seen a radical change in the attitudes and forms of learners (also in the results), when fathers and mothers have begun to participate in the learning process. That's the key to us. What happens? Often, in educational centers with a low socioeconomic profile, teachers, fathers and mothers, students themselves… have hardly any expectations”. Martinez works at the Elejabarri School in Bilbao. Elejabarri has about 80 students and 100% of the families of these students receive the Income Guarantee Income.

Juanan García, Professor: “One time a student told us he didn’t want vacation because on vacation he had belly pain. I mean, because I was hungry.”

In this academic journey, language is on several occasions a veritable headache. As explained by Ima Ortega, in some classrooms more than half of the classrooms have as their first language not the Basque or Spanish, and more time and effort is needed for the empowerment of the Basque Country. “With him who only knows Spanish it is easier, because I also know that language, and I will understand and act accordingly, even if I speak only to him in Basque. But the child who speaks to me Ukranian or Arabic does not understand him, and the cultural shock (our gesture, our way of speaking…) influences the difficulties of assimilating the language.” In Elejabarri, three years ago they became model D centers. For Martínez, “the essential thing is the importance that students attach to the Basque country, the feeling that Euskera generates in their daily lives, and that is what the context has to say: if they see that others use it and learn, they will do it in the same way”. The Basques who have money, however, are moving to other centres.

How many shared experiences

Citing those cited, the interviewees enthusiastically defend the diversity, involvement and project of their schools. They reject the prejudices and the bad image that exists around these centers. “Many think that in centers like ours students are conflicting, they fight each other. Not much less. The atmosphere is peaceful,” said García. “We are a school of ghettos, and in view of the panorama, things will not change in the short term, but we use a positive vision: how many stories do these students and families we do not know, how many experiences we share… Our school is very rich! – says Martínez – My approach is simple: I want a school where I can register my sons and daughters. Six years ago I wouldn’t take them to Elejabarri, today yes.”

Imanol Martínez, professor: “Our experience is that what conditions the student’s situation is not so much the socioeconomic situation, but the attitude of parents towards school”

Imanol Martinez came to Elejabarri six years ago. They identified three main problems: the lack of confidence of the parents in the school, the lack of closeness to the neighborhood and the conflictive coexistence. In these three axes, the focus was focused and the involvement of parents and agents of the environment was sought (“that this participation is not only going to meetings, but that it really gets involved in decisions, problems, measures…”); on the other hand, forces were put in the coexistence and the academic situation of the students. “As we gained the confidence of parents, we made us respect students and we were able to better address the academic aspect. Using interactive groups and dialogical tertulias, we approached the students in a different way, we managed to share their experiences and open ourselves to us”. At the request of their parents, they also started teaching for their parents, among other things, to be able to help their children with their home studies.

No money, no chances?

The economy also influences excursions and representations organized by the school. In Elejabarri, for example, you cannot make one-week departures, because parents do not have money for it, but shorter departures. Cervantes and Ganivet also lead students to free performances. “We have always made barnetegis,” says Ortega, but this year we have been half a classroom without going, because we have to pay EUR 120. And there has been a debate in the center: Is it fair to go? At the same time, do those who can lose this opportunity have to lose? We are reflecting on it… The exit is conditioned by money, but this is happening in more and more centers”.

Ima Ortega, professor: “This year we have half a class without going to the barnetegi, because you have to pay 120 euros. Debates have taken place at the centre: Is it fair to go? At the same time, do those who can do so have to miss this opportunity?”

Also in extracurricular activities, the shadow of poverty is long. A few years ago there was a waiting list for after-school activities organized by the association of parents of Miguel de Cervantes: “They had the pottery, the drawing, the football, the basketball… but now there is hardly anything, because you have to pay. Our students do not have the same opportunities as in other schools, and that is a great social injustice. The Administration should put monitors and resources.” In these cases, the involvement of the neighborhood is usually fundamental to ensure a decent leisure offer. In the case of Elejabarri, for example, the district’s Gazteleku encourages free activities.

More resources, less bureaucracy, recognition and support

For these centers, respondents have demanded more resources, human and material resources. Because they spend a lot of time on social services and social affairs, also on bureaucracy. “Only managing student scholarships is an incredible and complex task, in which we are all immersed in a bureaucracy of over 40 euros.” They proclaim their recognition: “We need more protection. What we are doing in public schools should be a priority for the administration – says Ima Ortega. It’s not worth playing the same with everyone; the ones we need the most, it’s up to us the most.”

They also consider it essential to put an end to the mobility of teachers and to stabilize the situation of teachers instead of receiving substitutes from zero each course. However, we have been emphasised that working in these types of schools requires awareness and involvement. “It’s also a challenge for teachers, knowing that we’re doing a very valuable job for these students to get through in life. The satisfaction is great, I don’t change my school,” says García.

.jpg)

Take out the others as they come in through a door

Beyond asking for more resources, the bottom line is another: to eliminate ghetto schools and to ensure varied and balanced schools that avoid the existence of primary, secondary and first and second schools. Today, the interviewees see this possibility very far. The reality is that we're creating artificial centers that aren't reflective of the environment. “We are not the only school in the neighborhood, but families start to enter and exit through the other door, a phenomenon that is repeated everywhere.”

In concerts, payment is an obstacle for families. Or they feel out of place and they just take a course in the middle. Most ghetto schools are public, and within public schools, families also take into account the reception and treatment provided by the center. “Depending on the commitment and work of the management teams, how they position themselves before the families, this influences”.

Ioseba Stackanez and Maika Diaz de Alda, parents: “Being afraid is normal, but then they are not real fears and they are overcome as prejudices”

Such centres are, to mention but a few, Urdaneta de Ordizia, Ondarreta de Andoain, García Galdeano de Txantrea (Pamplona) and Monte San Julián de Tudela. In Navarre, families with less economic resources are concentrated in centers with linguistic models such as A or G.

Among the many measures requested by the Administration to seek a balance between educational establishments, one of the main proposals is the Single Registration Office or Window, which will include trade union and family representatives, to facilitate centralisation of enrolment and the assurance of fair criteria. Ortega has made it clear that the political debate that needs to be held between all parties and between all school models is as follows: “We have to decide how we want to organize society, achieve political consensus on the issue.” For Martínez, “parents also have our share of responsibility and we have a rather hypocritical perspective on this issue.”

Ortega says that a balanced center is beneficial for everyone, because the interaction between the students is of great help, because the new students feel more integrated and enthusiastic, because those who do not know Euskera will learn more easily if they have an Euskaldun language at their side, because the teacher will more easily manage the classroom...

“If education does not embrace social cohesion, we have a party”

Middle class Basques do not always avoid such schools. “It is normal that there are fears, but then they are not real fears and they are overcome as prejudices. We took off the borders we had and we learned a great deal. Beyond the individual option, getting support is also important, getting the commitment and desire to work from some fathers and mothers, because you have to spend hours. Meanwhile, of course, you have to believe that your child is learning in the best place.” This has been explained to us by Ioseba Stackanez and Maika Diaz de Alda. Fifteen years ago, when the public school Ramón Bajo, in the Casco Viejo de Vitoria-Gasteiz, was a school of ghettos, his son was enrolled there. They also managed to turn the center of model A into model D, at the request of their parents.

.jpg)

They remember more complicated and better times, but both children have learned in this school and have made a fruitful journey, both in the relationships and in the areas of greatest impediment for many parents: the academic environment and language. “Moreover, the Basque language has been the axis of cohesion, because some students still did not have Spanish as a first or second language, and the Basque language has united them”. It is true that the center had few resources and the neighborhood has been indispensable in this work: people have been involved and made aware in the Casco Viejo, and the street has been an extension of the school that opened to the neighborhood and helped to meet their needs and needs. In extracurricular activities, for example, Ramón Bajo had few possibilities and created the Goian association to expand the offer of leisure.

Stackanez and Díaz de Alda make it clear: “If education does not embrace social cohesion, it is a party. It's dangerous to live in the bubble itself, and diversity is very good for everyone. There are parents who say they don’t want their children in a classroom full of strangers or poor people, who are afraid, but if we want a better society we have to fight, we can’t look away.”

Eskolaz kanpoko jardueren eskaintza zabala egiten duten ikastetxeen aldean, beste askok ez du horretarako aukerarik; eta eskola bereko ikasleen artean ere, denek ezin dute ekintzetan parte hartu, baliabide ekonomikoek baldintzatuta. Esku hartzeko dei egin diete instituzioei:... [+]