Biometrics and control in the European Union

- The EU authorities plan to create an integrated control system for fingerprints, emotiveness, genetic information and personal data. Although it is designed for refugees and immigrants, the system could welcome all European citizens.

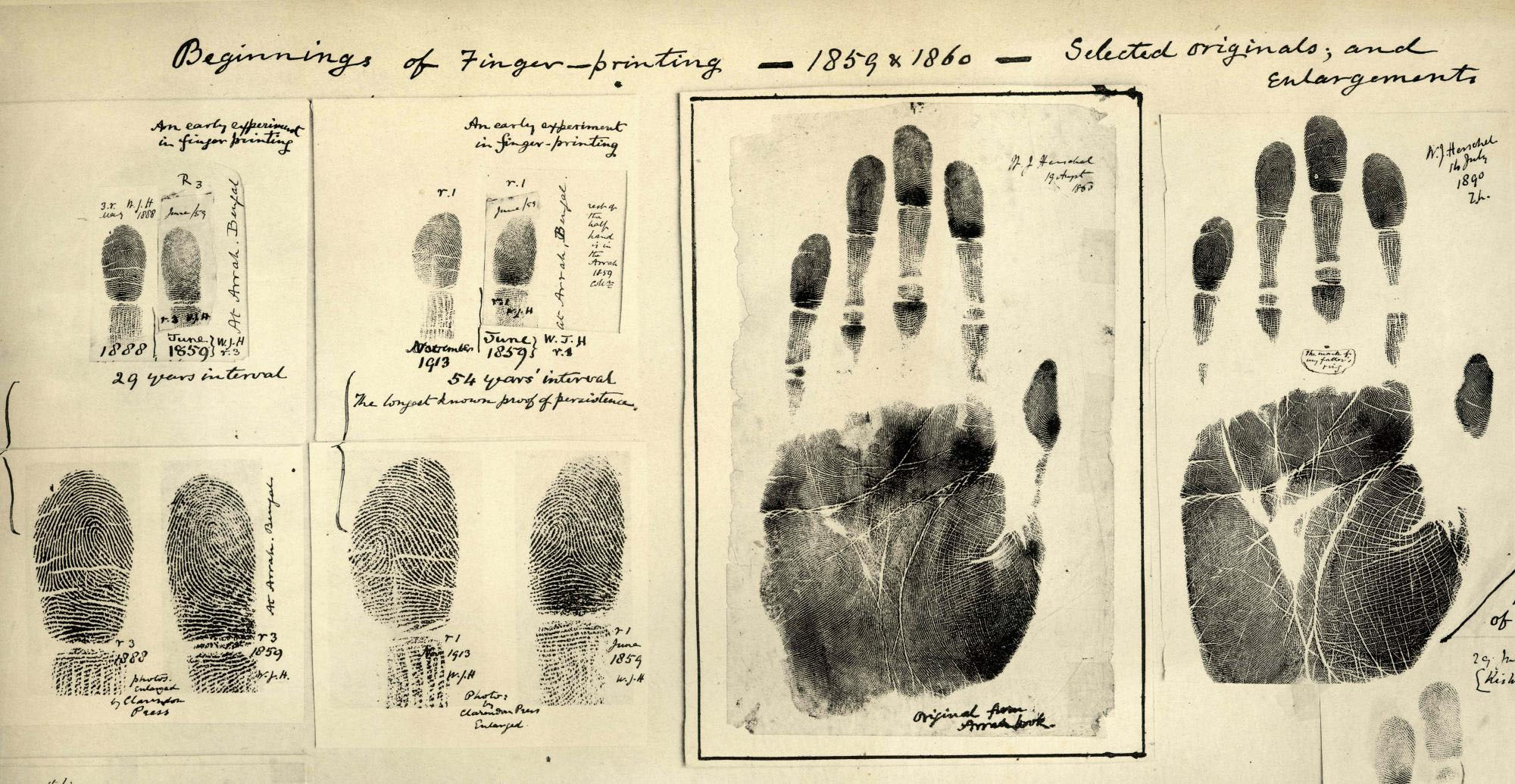

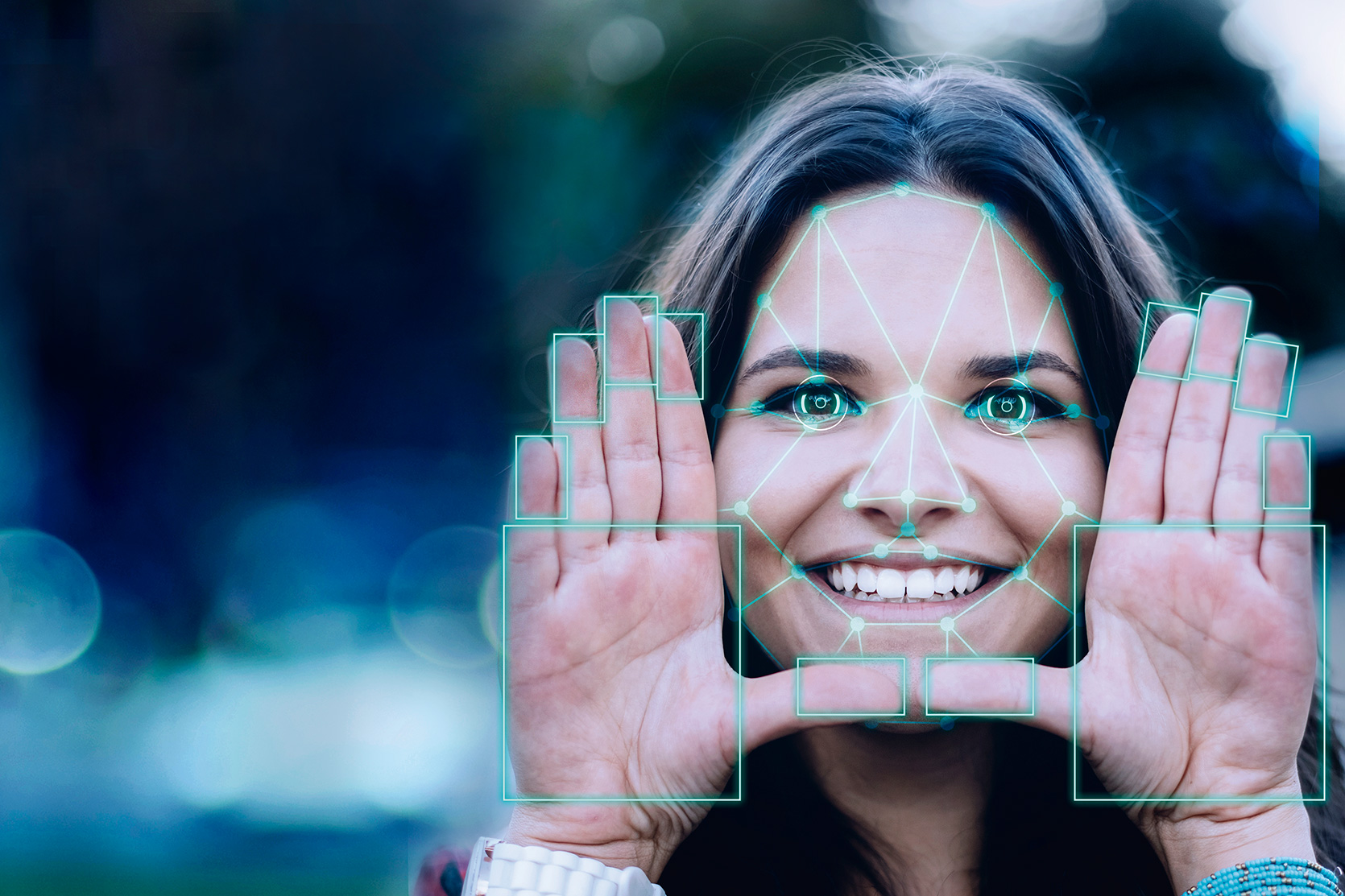

Biometrics is everything that turns your body into your passport. Or, as defined in the General European Data Protection Regulation adopted in 2016, biometric information consists of personal data obtained from processing the physical, physiological or behavioural characteristics of a person for unique and reliable identification.

Fingerprints, facial recognition and DNA are the most commonly used characteristics in the world, and the most commonly used by European public institutions. Other systems study the shape of people's hands, veins of fingers and wrists or behavioral patterns; others focus on voice, iris or retina, writing or chemical composition of body odor.

Since 2013,

due to the increase in the refugee population and asylum seekers, biometrics has been a key element in the

expansion of the ‘Fortress Europe’

The propensity to use biometric systems to verify in the most reliable way the identity of people entering a country or continent has spread throughout the world since 11 September 2001. Airports and borders have become critical infrastructures that, according to the official discourse, are access to the "worst threats", even in the collective imaginary. As a result of the current migratory crisis and especially from 2013 – due to the increase in the number of refugees and asylum seekers – biometrics has been a key element in the expansion of what is known as Fortress Europe and has become a technological, economic and legislative priority, both in the EU countries and internationally.

Governments, businesses and even NGOs are systematically expanding the technical means to obtain as much information as possible based on the bodily characteristics of all people entering, leaving or transiting through Europe, mainly in the area of care and security. This is precisely what biometric control is about. It is estimated that in 2020 the EU will receive biometric information from 218 million immigrants and asylum seekers, including passenger data from other continents, as well as information on five hundred million EU citizens.

Unlike biographical

data, biometric data indicate that it is difficult to classify the population by race and gender, but prejudices can influence them when accessing them. Studies on biometric technology show that the percentage of errors in these systems is not only small, but also reinforces the inequality of ethnicity, race, gender and social class. “Biometric systems are designed in the West, mainly white men. They do not work in the same way with all people and make more mistakes in identifying racialized people, for example,” says Chris Jones researcher and activist Statewatch and European Digital Rights.

Distortion of this information can turn

databases into a dangerous tool against fundamental rights.

On the other hand, there are studies that indicate –Nichole A. Fournier and Ann H. Ross, for example, published in 2015 in the journal American Journal of Physical Anthropology, aims to know the sex and geographic origin of people through fingerprints, as well as other data collection techniques that are currently being developed.

As for gender, the obsession with identity verification and its determination (especially at airports) reinforces the forced normalization of certain bodies, behaviors and identities, as has been repeatedly denounced by trans activists, especially in the United States.

Although the main biometric control applications are mainly targeted at immigrants and racialised people of non-European origin, there are plans to extend interoperable access to EU databases which already have biographical and biometric information from European citizens through the Prüm system. The Prüm system collects vehicle license plates, DNA, fingerprints and passenger register (PNR) data. According to the Transnational Institute, the PNR “suspects all passengers of a flight, automatically and for no previous reason.”

It is also difficult not to intimidate the dimension and content of the data that these interoperable systems will receive, and especially the use that will be given to them. In this regard, the European Data Protection Supervisor warns that “if this information fails, databases can become a dangerous instrument against fundamental rights”.

.jpg)

“The far right could get biometric data from 218 million people”

Chris Jones (Essex, 1985) is a researcher on public policy, migration, militarism and security in the United Kingdom and the European Union, and a member of Statewatch since 2010. This non-profit body conducts a critical investigation into European internal problems, civil rights and freedoms, privacy and justice. It has just published a report on the rise of the EU’s industrial security complex.

What is biometric control and how do they justify it?Biometric control measures a supposedly isolated characteristic of a person to check their identity, information that is stored in a database or compared to an example or sample

to detect possible coincidences. A biometric characteristic can be a fingerprint, an image of the face, a fingerprint of the palm of the hand, the passage of a person, the model of the veins... New features appear every week. Its use has expanded in recent years. Mobile phones and laptops, for example, have biometric security systems and are also used by military companies and organizations to control access to their offices and buildings. Large-scale examples, however, large databases are implemented by governments, especially in a political context such as the current one, which use “threats” such as terrorism and migration as a pretext to further extend biometric control.

When and how did they switch from using biometric systems as tools for migration control and asylum management to fighting crime and terrorism? How have biometric technologies become a safety issue? European

institutions and governments have been trying for years to turn biometric systems into a source of information for the police. In the case of the Schengen Visa Information System (VIS) database, it was decided in 2008 that it could be used by the police, even if the decision was not implemented until the end of 2013.

The case of the Eurodac system, which contains the fingerprints of those claiming the right of asylum, provoked a greater stir, as in 2012 they decided to amend their legislation to allow the police to use that database under certain conditions, although initially their sole objective was to manage asylum applications. In this database, it is also intended to collect data from “irregular” immigrants who have suffered this disease. In both cases, these measures violate a basic principle of data protection: the principle of limited use of information. These data already existed in these databases prior to the reform that allows for a different use from the one they originated and were not collected for the purpose now intended. Furthermore, the fact that the police can access these data raises suspicions about applicants for visas or asylum, as it suggests a greater predisposition to commit crimes.

This trend already existed, but it has now accelerated with the emergence of new systems and the interconnection of existing systems and all future systems.

The European Commission considers that biometric control of people from other countries is fundamental to the fight against terrorism in Europe. But many of the attacks in Europe have been carried out by people of EU nationality. What do you say to me?

Well, the European Commission has never put forward any particularly profound arguments to justify its initiatives. It confuses and confuses in an absolutely irresponsible and naturalised way the management of “migratory flows” and the fight against terrorism. The Commission seems to see a logical link between migration and terrorism, or that is the image they want to present.

.jpg)

The new systems and databases (SEEs, ECRIS, ETIAS) that apply, how are they going to affect people who are racialized?All these systems

are currently used with people from other countries, so it is clear that they collect data from a large number of people who are racialized. It is estimated that there are some 218 million non-European citizens who have received data from their public accounts. As for the ECRIS-TCN, the judicial systems of each country should reflect racial prejudice. Since irregular immigrants, foreigners and racialized persons are more likely to be punished or to have a background than “whites”, there is also a greater chance that their data will be made available transnational as a result of their being collected in systems such as those cited.

Most worrying is the implementation of the Outgoing Access System (ESS), whose functioning will depend on a massive national control infrastructure. If someone enters the EU and stays longer than allowed, the system will alert the authorities. Since these people will not be able to locate them automatically, road checks will be carried out and it is known that the police have a rather high tendency to categorize them by race. There is therefore a great risk that this new system will further strengthen the current trend.

“One of the biggest risks

is to think that governments and state institutions always act and act responsibly and

that everything is going to go well.”

And as for political activists?It is clear

that these databases will be useful, in one way or another, against activists or politically qualified people as “malicious”. However, SIS is the most important system in this respect. The system is expanding to get more data, like DNA. SIS allows for the creation of surveillance alerts, for example on people entering terrorist groups, but it has also been used to monitor and control the movement of political activists.

What can happen if the information gathered in these biometric databases fell into the wrong hands, for example, of the far right, which is becoming stronger in Europe?

Connecting European databases to each other and creating a single biometric data register can be a very tempting target for hackers. As we've seen in other cases, there could be massive blackmail, with very private data. If the extreme right comes to power, all this data, including those of visa applicants, will be made available automatically. One of the greatest risks of this interoperability experiment is to think that governments and state institutions always act and act responsibly and that, if data is misused, there will be compensation and everything will be fine. European history teaches us that things may not be that way and that people’s registers are used for dangerous purposes, if brutal racist governments gain power.

To what extent does interoperability pose

a threat to the rights of all European citizens?The European Commission says that, except for the SIS, data collection and interconnection are addressed exclusively to citizens from ‘other countries’. It is, however, insulting to say that we do not have to worry about systems that harm other people’s rights. Despite this issue, they intend to connect more databases and data systems that already have a lot of information about European citizens, such as the Prüm system (DNA shared registration, fingerprint and vehicle registration) and the PNR (passenger registers for trans-European flights to Europe). These systems have already begun to be connected. Threats are in a number of ways.

This data is very appealing to hackers and other governments and powers, or you can get inaccurate data from different databases and it's very difficult to fix them. The biggest threat, however, is that the creation of a mass surveillance system cannot be compatible with societies supposedly based on the rights and freedoms of individuals.

Wikipedian bilatu dut hitza, eta honela ulertu dut irakurritakoa: errealitatea arrazionalizatzeko metodologia da burokrazia, errealitatea ulergarriago egingo duten kontzeptuetara murrizteko bidean. Errealitatea bera ulertzeko eta kontrolatzeko helburua du, beraz.

Munduko... [+]

Europar Batasunean berriki onartu den Migrazio Itunak, asko zaildu dizkie gauzak euren herrialdetik ihesi doazen eta asiloa eskatzen duten pertsonei. Eskuin muturraren tesiak ogi tartean irentsita, migratzaileentzako kontrol neurri zorrotzagoak onartu dituzte Estrasburgon,... [+]

In the Basque Parliament, the legislative amendment to the Basque System for Inclusion and Income Guarantee has advanced. We need to look at the debate on the law, the agreements on the left and the right to amend it, and at the limited impact that the reforms brought about by... [+]

Video surveillance is not something new on our streets, neither in San Sebastian, nor in Euskal Herria, but what is especially serious is that the increase in smart video surveillance, which implies increased security and social control, is taking place without any kind of... [+]