"The working class is reduced to an identity account in the diversity market"

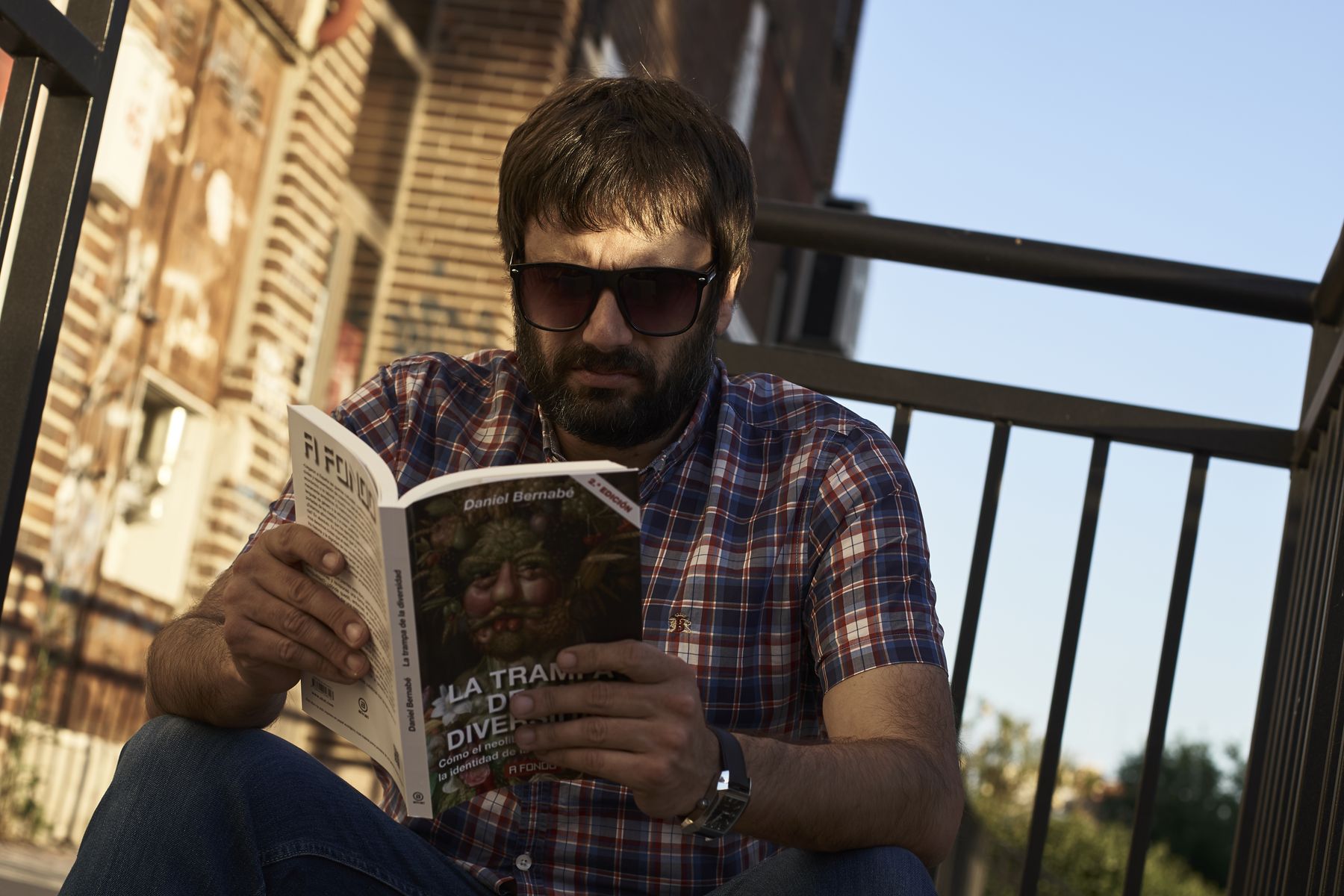

- The writer and journalist Daniel Bernabé (Madrid, 1980) was interviewed on the occasion of the publication of his latest book, The Trap of Diversity (Akal, 2018). In just two months, it has already had its third edition, and it has provoked a lot of stir, strong debates on the networks, a sign that the issues it deals with raise curiosity and itching.

His book can be regarded as a challenge to the consequences of postmodernism. How do you define the postmodernism that Fredric Jameson considers the cultural logic of late capitalism and its consequences? Those philosophical and

political concepts can be pretty big for me, as a writer. I wanted to analyse the consequences of postmodernism in our society and in our political activity. Postmodernism has become a spirit of an era and it is not about what the authors considered so many post-modernists said in their books, but how neoliberalism used these books and theories to oppose the universal spirit of Marxism and incorporate to the left permanent doubt, trying to avoid the repetition of some forms that were successful in the twentieth century, that provoked the revolutions and that the people take power.

Unlike other more descriptive currents that theorize on the material fact, postmodernism was a kind of self-destructive prognosis of the future, as if they had seen that those theories, outside the academic sphere, could serve to properly fragment and integrate into the popular imaginary, to reduce the politics of the left.

Since the 1970s, language and semantics have assumed enormous importance and many conflicts have been limited to the field of representation. Is this a word based activism? How does it work and what does it hide?

Activism based on semantics is more a consequence than a fact. In the book, I've tried to draw how our relationship with politics has changed over the last forty years. In it, I talk about feminism and the labor movement, among other things, but it's not a book in itself about these issues. These are the struggles that occur in society and that is why I mentioned them, but without any intention of giving any instruction to feminism or any other policy. In any case, I believe that my book can make a contribution to the insistence that some things are not going well, because the Left — in the broadest sense, from traditional social democracy to radical movements — has lost much of its influence in the structural sectors of society and is being relegated to symbolic issues.

In the United States, for example, there is a serious problem of racism and there are lawless police killings on the streets, but if a journalist or a public character uses the Nigger word, it would immediately be left out of the media system. And that reflects a very worrying paradox: the real problem is still there, even if it wins the battle of its symbolic representation.

“As in neoliberalism diversity takes the form of a market, it says that identity uniqueness brings value” and that there is competition between oppression. In what sense?

The other day I read an article on “surrogate pregnancy.” In it, we were presented with a person who was in favor of this practice: non-binary, black, gypsy, Jewish and “of working-class origin”. In other words, it seems that, the more specific a person is, the more rights he has, in this case, to exploit a poor woman and turn her into a child producer.

Another issue I've worked on is that since the 1970s, the three solid identities -- religious, class and national -- that came together in the 20th century began to blur. That desert had to fill itself with something, and that was an aspirational middle class. It's not an authentic middle class, but a collective cultural identity that we all want to be. The workers want to be of that kind and the bosses put that class in the middle, as a screen, so that they hide behind it. This aspirational middle class is in itself very homogenizing, so everyone feels the need to add their specific characteristics in order to compete in the diversity market. In the end, lifestyles and political identity are confused and we do not know what we are talking about, ideology or hobby.

What do you think of outrage and “activism” based on individualistic narcissistic victimization? The people

who, as activists, use this articulation to achieve their goals, seem to me to be the hardest hit here. Because while it is true that at first they can draw the attention of their environment, in the end it seems that this is their only objective, to compete in the market of visibility and to be at the heart of the public debate, and not to make concrete political action on a particular problem.

And what's the problem? For that is only a symptom and ends up bringing everything to the individual: any criticism made in the ideological sphere is finally transferred to the emotiveness itself. On Twitter, I've been a little bit critical, but those few have been terribly tough, but they haven't joined the book content, of course. The truth is that some people had found an excellent way to be visible in the diversity market and suddenly they have felt assaulted, but not at a political level, but at a personal level.

As for the person who appeared in the article on surrogate pregnancy, for example, it was said that he had “origin in the worker”. In this kind of thing we can see how the working class, which in itself was a category linked to production, is revealed to us also through an identity, has been reduced to a mere question of identity, and how all social identities shared that, which was the working class, have made it another identity. This is one of the big problems we face: that we've forgotten that most of us are working-class, just for statistical reasons.

.jpg)

According to his thesis, through the policies of the self and diversity the market offers us innumerable possibilities to make known our individuality, but without all the decisions that correspond to our material conditions of life. Developing that idea?

Margaret Thatcher already delivered unequal in her investiture speech by taking over the leadership of her party in 1975, when she became president of the government. In English, this word has two meanings: one unequivocal and another distinct. Thatcher equated both meanings, and until then the structural inequality driven by an economic system became a mere inequality, a delicious inequality that we could work to compete with each other and be the most different. The funny thing is that neoliberalism has very much homogenized us in recent decades: we all buy linens at Zara Home, we all eat equal burgers, we all go to the same sites, the movies are increasingly similar and most books are identical.

Faced with this great trend towards homogenization, we see how until the advanced stage of late capitalism, until the late 1970s, the individual who sought handles to find their difference, now loses that grip and has to start competing in that market, exaggerating its particularities, although in the case of many people they are imposed from outside.

You say that “neoliberalism will not miss the opportunity to phagocyte the women’s movement and will be turned off but with great potential to compete in the diversity market.” If there is a hopeful movement right now, that is feminism, as we have seen in the mobilizations of 8

March and in the prostems against The herd. On social media, I'm always told that I'm a male chauvinist, and I want to make my position clear. I sincerely say that this is the most hopeful movement.

But what's the problem? Well, when Time magazine chooses the feminist as a character of the year, seeing the characters they have chosen in the last hundred years, we see that behind that decision there are clearly political intentions. Stalin was elected as an ally of the United States; an American soldier in the Iraq War; in the Arab spring, the proester, last year, a feminist. So, I always say, "Be careful with your enemies or with what you criticize, but with more care with those who applaud you."

On March 8, for example, a journal published an article: “T-shirts you should wear on March 8,” in the title. I mean, it's imperative that you wear that clothes to be a feminist. Mango had made those t-shirts with feminist slogans. And at the same time, another piece of news tells you that Mango has fired a worker for being pregnant and that to make her own T-shirts she uses Syrian refugees in slavery conditions.

In view of this, the usual reaction on Twitter would be: “You’re saying that the fault of child exploitation is feminism.” No, what I'm saying is that capitalism is not stupid, that it has almost spoiled us all, and that it's going to try feminism. They will not leave the class feminism or the fighting feminism that goes against the structural foundations of women's oppression. They'll try to do something soft and nice, individual and declarative. “I’m a feminist because I say I’m a feminist.” No, feminism is a political activity. It takes more than words: you have to join other people who think like you and do something.

She's been criticized by some feminist militants, right? Are there any criticisms that I think are well-founded?

The criticisms made to me by some feminists in a discussion about the book seemed pretty reasonable to me. They said: "We have finally managed to articulate our discourse in some way, and here you, my man, come to object to our issue, especially as regards oppression and privilege, when, apparently, we were working well..." Any criticism seems legitimate to me if it is made from an ideological or political point of view, and that criticism was absolutely ideological. I didn't have to agree with him, but I perfectly understood what he was responding to.

But I find it wrong that many of those who oppose my book have not opened it up, and say that I say that the only struggle that matters is that of white and cysheterosexual men, and that the rest of the struggles are nothing but nonsense. And that's not true. It's a lie. That is not a political critique, it is a critique that responds to ignorance or misintent. What is to be done against this? I don't know.

"To say that you have to rule out anything a man has to say about a subject that affects women, because it is considered an imposition, that the possibility of opinion is equal to that of being linked to identity," he says. What do you mean?

I understand that women 0 have had a huge voice deficit, until very recently, and now women have more voice possibilities, although actually some women do. There is a greater presence of women in the media, but there are also some specific classes and ideologies. Can this be seen as a victory? It is up to you to decide, but many women in my environment say that in the end the same women always end up talking.

With regard to mansplaining, it is true that men are predisposed to impose our views and we have always had the opportunity to speak. I always try to put myself in the background when there is talk of a feminist issue, but, at the same time, I can be accused of being sidelined. And so what exactly do I have to do? Do you stay quiet? Talk? What happens is that when two adults are discussing, on an equal footing, no one tries to impose their opinion, they are arguing. Is my opinion heavier because I'm a man? Well, no. Of course, there will be things I don't see, because I'm a man and I don't have them directly ... This doesn't mean that if I've had a good idea, because I'm a man, you have to discard it and teach it right away the meme "Turkey, shut up" (Tire, treasure). I understand, of course, that women are up to the chin, because men cut you continuously ... But I'm very angry about that answer when it's being used in a cheat way, because you don't like what you're hearing in a discussion. And also, you're faced with the fact that you're imposing your opinion. No, I'm not imposing anything. We're talking as adults.

In any case, and to conclude, we can only talk about what we are dealing with. I mean, can't I talk about the Catalan question being Madrid? Or can the Catalans say nothing about what is happening in Gaza? Attention, because throughout the twentieth century it has become clear what happens to these collectives, which has meant that some groups in society consider themselves incapable of making opposition. This attitude is obscure and malicious.

.jpg)

Changing the theme a little, what is the role of culture?Culture

is the substrate in which legitimacy arises in the political sphere. Simple power is too brutal for most people to accept or respect it without further ado, so cultural forms are needed to make it acceptable. This is one of the most important functions of culture in the political sphere, and that is why some political options are considered reasonable, even if they are well-founded, and despite being a theoretical corpus that has proved useful in some historical moments, they are considered, above all, impossible to materialize. Culture limits what is tolerable, what is left inside the wall, and what is left out of it.

Cultural fact has become very important in recent times, but in the end it gives the impression that culture is the only war that matters. In the 20th century, instead, politics was about doing things. Now it seems that it will simply happen to express what we want to do. Every time one of these cultural and representational conflicts gets on the table, we must ask ourselves: “How much money will the public administration invest in this project?” Campaigning is all very well, but it is also all very well to put concrete solutions in place.

Each time one of these conflicts linked to culture and representation arises the following question: How much money will the public administration invest in this or that project? ". The implementation of campaigns is very good, and it is certainly necessary, but it is also very good that concrete solutions are put forward. Just over a year ago, the Community of Madrid suffered a serious occupational problem and dismissed workers in the telephone service against male violence. As I said, campaigns and they're great, but if you're cutting money for these accounts, we have a problem.

What are “cultural wars”? Where do you locate them and what do you think their function is?

It seems to me that cultural wars are a matter for the United States. We have brought them into the European context, but I think they are a bad business: they are the result of moving politics only in the symbolic field, leaving it to the right to deal with the economy. Recognizing that there is only one possible economy and that there is a single way of managing the economy, it seems that in the end we have only to fight on these cultural issues. The cultural wars that came to the Spanish state with the government of Zapatero, a right-wing government in economics that had to appear before its voters, were still on the left.

You have a critical view of bringing here uncritical terms — privilege, self-analysis — used in the context of the American will. Can this criticism be developed?

That idea isn't the one that's at the bottom of the book. I have offered you only two or three pages, but the truth is that it has caused a lot of jaleo. What I say is that since the individualization process of politics took place, nowadays everything tends to move it to the individual and the aspirational, rather than to the class and collective sphere. When I say aspirational, I mean something almost declarative: what we say is that we are the same as what we are, and therefore, we do not try to act coherently in our daily lives, but to create a narrative through ourselves.

I do not deny that there is a man who is examined and says: "As I have grown up and been educated in a patriarchal society, I have many macho tendencies and I will try to correct them." Of course it can happen. And I recognize, of course, that we live in a patriarchal society and that men are macho. But what I am saying is that, in general, I find it pointless for all men to try to change through a process of self-analysis. It seemed like a Catholic sin to look inside oneself ... And you do not believe that I have a solution to this issue. In any case, this question of self-analysis has never been a classic way of acting on the left in the 20th century. Throughout history, when a social class has had systemic advantages — I think this term is more appropriate than that of privilege — that class has not renounced these advantages without a struggle that has faced the structural foundations of the case. And here's something that fails.

And what do you think of the concept of

“cultural appropriation”? This concept has also come to a large extent from the United States. It was created by the African-American population, seeing how the capitalist system in the hands of whites continuously appropriated the cultural resistances created by themselves, their peculiar characteristics, their way of confronting oppression and of cohesiveness as a group…, for what and for what it is a system of seeing and that they are reasonable.

In our setting, this concept is sometimes used at the micro level, out of proportion. And this is one of the most serious problems of today's activism: once the structural conditions have been completely discarded, it focuses on the details, completely forgetting the overall view of how the system works. As within postmodern logic everything is imperceptible and too complex, so we focus on the specific.

Can we consider capillary traces as a cultural appropriation? Well, I don't think people who live in Jamaica care very much about what a man from Cuenca does. The problem is that racist elements are not only cultural, but that racism is the cultural expression of an economic fact. Because some social and ethnic groups have to explode, it was invented that some people are below us, and that's where supremacism emerged.

There is in his book a kind of nostalgia for what he could not be. What, in your view, would be the political proposal to be developed by the Left to deal here and now with the present post-modern that is living on us?

Nostalgia is a sticky element that grabs you by your neck and doesn't let you move forward. It's impossible to go back to the place we've been before, because context is never the same as what we think. In this sense, the Left is becoming one more group of diversity and the members of the Left exploit their identity characteristics in order to compete in the diversity market. Many young people have discovered communism as a result of the crisis, the truth, but they have only discovered it in an identity form: Lenin's photographs and red flags are placed on their Facebook or Twitter profiles, but as identity signs.

If the Left wants to remain alive and does not want to be reduced to another group of diversity, it has to get out of that mess and cannot do so through nostalgia. That does not mean that we cannot draw conclusions from what can be done from enlightenment, socialism and modernity in general. Because with reason, with arguments, with consciousness and with technology, and with a class perspective, the world can transform itself. It seems to me that this idea is still reasonable. And if we add to that everything we have learned, that women are not a secondary social group, that everyone must be respected despite their sexual orientation, that Europe cannot impose its vision around the world, etc., much better.

If that is the case, despite the concrete results, I believe that we must bear in mind that socialism spread throughout the world: Africa, Asia, Europe and Latin America. It would be a good thing if people from such different places and classes considered it as their own idea that they could adapt to their context. I think we should get those ideas back, and that's what I said in my book. Right now I'm trying to say that we live on the island of King Kong, an island that we don't know where it is and has no time. Our time is like the island of Kingo Kongen: we don't know where we are and we lack the measure of time. We have no past. Something confused happened, we recover nostalgic things from that past, and we're facing a futureless future: we don't want to revolutionize anymore. In this continuum, it is very difficult to imagine ourselves and to know where we want to go and where we depart from. Another idea that stands out a lot in the book is how to recover the solution. The book doesn't want to be a guide to anything. He wants to hit the table and says: "Come on, let's stop for a moment and see where we're going." We are sharing with neoliberals the idea of the end of history, without realizing it.

Finally, does it consider it appropriate that projects of enlightenment, socialism or modernity should be eternally or eurocentric?

As a consequence of historical development, in the fourteenth century changes took place in the Arab world, since the eighteenth century changes began to take place in Europe. This does not mean that the ideas of the revolution are only Western. The good thing that ideas have is that, if they're good, they're not owned by anyone; and if they're useful to humanity, anyone can take advantage of them. In this sense, although the idea of socialism was formulated by a German man, I do not believe that when the peasants rose up against the government in Bolivia, they were thinking that the Germans imposed nothing on them, but that they had received a good idea and were adapting to their context as they could.

“Houston, we have a problem!”

Well, to say that we have a single problem, as things are, can be a temerity, but this time I want to focus on an issue that concerns us and affects us internally, mental health.

Historically, suffering has had a profound meaning and meaning... [+]