Whenever laughter hits in the same direction...

- What is humor? A naive question can be complicated as much as you like. Why do we laugh at some things and others? Is the smile natural to us, or are we taught to laugh about what and who? Because humor almost always favors power, many times from top to bottom. Subject and object. Who to whom. This is one of the keys. Gender, race, identity, nationality -- humor marks hierarchies. In the first part of the report we address the national identity. The sociologist Uxoa Anduaga explains that the Basques have the hegemonic discourse of the state more assimilated than we imagine, and that it is a reflection of this, in part, the belief that laughing at ourselves is very healthy, without taking into account that humor always hits in the same direction (almost). Self-parody will be honest and constructive if power relations are equal. We have been taught this by diversion, by the arts that combine humor and denunciation. Kamila Gratien, garaztil, has explained the creative process to us. We have also talked to cartoonists Patxi Huarte Zaldieroa and Joseba Larratxe, to the extent that graphic shoots can be a tool to seduce power.

On 15 May, DIBUJANTE Dieter Hanitzsch published in the German newspaper Suddeutsche Zeitung the cartoon of Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu. Netanyahu, dressed as the Israeli singer Netta Barzilai, who was the winner of the Eurovision contest, appears with the missionary in his hand and from his lips comes this phrase: “Next year in Jerusalem.” The drawing generated a great controversy, as many believe that they reproduced anti-Semitic stereotypes. Forced by pressure, the newspaper apologized and expelled the CARTOONIST. He had previously carried out demolishing cartoons of well-known leaders, such as those of Turkey’s President, Recep Tayyip Erdogan. In these cases, however, they defended the freedom of the press and expression of those who later threw the glove on his shoulder.

In February of last year, in the sixth ETB1 Euskalduna naiz and zu programme they talked about the stereotypes that exist about the Spaniards when the protagonists were the Euskaldunes in the previous five. In a drawing of humor they were called “facha”, “paleto” and “chau”, which are the topics reproduced in the Spanish series Aída. ETB1, however, generated a great controversy because, according to many, it insulted and fuelled hatred for the Spaniards. Under pressure, ETB felt “offended” for asking for forgiveness from the citizens and erased any trace of the sixth and final chapter from its supports. Not only public television, but also the lehendakari of the Basque Country, Iñigo Urkullu, said he assumed the “feeling of offense” caused by the program. Programs that reflected stereotypes (especially Basques) that ETB already issued earlier, such as Go Semanita. However, this program was criticized by very few for teaching to “laugh at oneself”, and for giving two other examples, the films Ocho Apelsuras Vascos and Mission Pays Basque. Perhaps seeing those films would have been tempted even to clap with the ears (they are so funny! ). But it is also possible, as happened to many Basques, to be tempted to put the popcorn bought in the film court to the authors and producers separately from the background. If you are one of those, you will surely have heard that things are becoming crazy, that you have no sense of humor, that freedom of expression is sacred and that it is time to learn to laugh at yourself. To contribute to this, ETB created a reality that revolved around the north-south relationship (in the Spanish coordinates), You to the north and I to the south. Andaluces and Basques are once again stepping their heels.

Leaving aside that we have no right not to be offended, as we were reminded in an interview by the members of TMEO magazine (No. 2.553 of ARGIA), the cases of Germany and ETB perfectly summarize some of the conclusions drawn in the thesis of PhD in sociology Uxoa Anduaga on the analysis of the symbolic regeneration of the Basque nation through ethnic humor.

On the one hand, the non-hegemonic speeches were those that took measures to neutralize the things (power relations) that the agents who want to keep intact, that served to remember who has the monopoly of “normality” and recover the established order. Thus, we have been able to see what is the three-step protocol applied to practices that alter the status quo: that of redefinition (“they are not humor”), that of censorship and punishment of speech (“because the discourse is not humour it loses legitimacy and, therefore, its dissemination must be cut”) and, finally, the step that reaffirms the subordinate position of those who ‘have done harm’, that of barbarism. The third is an essential step to return to the order before the production of the damage, remembering the creator or user of said discourses that they do not have the right to have their own perspectives and opinions. [The theoretical quotes on the thesis of Uxoa Anduaga are included in the 220 issue of Jakin magazine (May-June 2017). Under the title Humor is political, he collected texts from Anduaga, Iñigo Aranbarri, Unai Iturriaga, Laura Mintegi, Mario Zubiaga and Edorta Arana]

On the other hand, Anduaga says that ‘laughing at oneself’ is the result of a power relationship, it is the victory of an agent who has had more means to impose a discourse. As he has taken advantage of humor, he has been integrated into society without apparent violence. We'll throw it away.

Laughing at ourselves, as healthy as we thought?

Pays Basque, Eight Basque surnames, Go semanita... In Anduaga’s words, all these productions transmit “the image of a determined national normality”. It is noteworthy the impulse of the media and ‘public opinion’ at the state level, which reaffirm the contents consistent with the Spanish and French national culture: the defensive use of Spanish, an area that does not take into account the seven historical territories, an identity that does not recognize nationality and that is based on the regionalist particularities… “This type of ethnic humour conveys to society a message that the Basque identity is an absolute French anomaly. But, you see, what should be insulting to the Basques is very successful in Basque society, especially in Hegoalde. “We have absolutely internalized the speeches of the Spanish State. I flipped when I went to the movies to see Eight Basque surnames and in the end almost everyone started to applaud.” In his words, we have assimilated the ridiculous figure of the peasant, the discourse Gipuzkoa vs Bizkaia, the topic that there is nothing outside the CAPV... “We’ve made them our own, and they don’t give us pain from the flow we’ve suffered for years.”

To some extent we have believed that laughing at ourselves is healthy, natural, within the logic in which we are not conscious. “Contrary to general sociological theories of humor, much of the ethnic humor that is made in the Basque Country does not parody their neighborhood (Spain or France), but uses references about their team for humor, to the point that it is a widespread belief that the Basques ‘laugh at ourselves’.”

“I find it very painful,” Anduaga says. “Let the agent who has barely tried to laugh at himself, owner of the hegemonic discourse, say what the Basques have to do…” It was the sociologist who linked it to the political situation: “When the PP was in power – between 1996 and 2004 – the Basque stereotype had little sense of humor, it was more a radical and dangerous Basque. But soon after, at the time of the PSOE, the figure of the humorous Basque gained strength, and that is where the Vaya Semanita himself can be located. ‘The Basques have learned to laugh at themselves,’ the media headlines said. We were fooled. No, when a citizen, let's say a little boy, saw the parody of a peasant in Vaya Semanita, he wouldn't feel that they laughed at himself, but at the expense of the farmer, of the breast of that figure that adheres to the Basque folklore."

What is humor? “It’s a political mediation,” Anduaga says: “Humor, in a vacuum, is social, it is something that is learned and reproduced, that is continuously being built, that is far from natural or natural and that has the capacity to influence society. There is no white, dumb or muddy humor, because it always conveys a judgment – an assessment between what is good and what is not –”. In this regard, bertsolari Unai Iturriaga says: “We all judge when humor and humor we do (all).” |

Comic imaginary to hit the Basque identity

Spain has long used comic representations of the Basques, the string of the ‘biscayno’, “which, in addition to delegitimizing Basque nationalism, contributed to reaffirm the authority of the Spanish State and increased the shame for our identity”, as read in Anduaga’s thesis. “In Franco, the regime’s reading of the language – the Basque language – united language, identity and pride; beating one of them would suffice to collapse the other two. In addition to prohibiting the Basque language, he set in motion a process of disrepute, revealing the convictions that the Basque language is a retrograde, clumsy, limited or peasant language through humor, stepping the self-esteem (pride) of the speakers and opening the gap in the Basque institution.” He showed that humor is an effective means of strengthening authority.

With the beginning of the new century, this type of humor achieved unprecedented social success until then, with the symbol of Vaya Semanita. The program had a great peculiarity that the author was not Spanish, but Basque (EITB), although he used the same language: Spanish. In Anduaga's words, it is more effective than the Basque country to internalize discourses, in addition to sociolinguistic factors, only by statistics, that is, because there are more people who understand it. “All this raudal of humor around the Basque nation has influenced the assimilation of its discourse and form.”

The trivialization of the conflict Mario Zubiaga and Edorta Arana (UPV/EHU teachers) in Jakin magazine: “In the Basque conflict there have also been processes of banalization, especially in recent times. Humor has been the instrument for this, with the tools of mass culture, television and cinema. (…) The political content of the conflict and its causes disappear for the benefit of the topics that feed the status quo of power. We are not going to put at the same level the ‘palliative’ impact that Vaya Semanita has had in the raw moments of the conflict, nor the film Eight Basque surnames that has been a great accompaniment in Spain in calmer times. However, both show what Uxoa Anduaga has shown in his thesis: Power, especially institutions and institutions, defines what is and what is not humor.” |

Whatsapp machista joke

Power relations may be related to national identity, but they are present in all areas of life and are all marked by humor.

Suppose, for example, that around March 8 you came up with a machist joke from WhatsApp and that, being so ridiculous, you decided to share it with more friends, although, in theory, you are critical of the rules established by the heteropatriarchal power system. What does that show? “As the whole environment is heteropatriarchal, we reproduce often in this way, without being aware many times; even through humor, some speeches that we do not take for good with our work. That’s why it’s much harder to find feminist jokes.”

In the same sense, the writer Iñigo Aranbarri speaks in Jakin magazine: “Making a grumpy, classicist, racist, machista humor is not difficult. We have training for centuries, it grows in the structures of a settled society, and as we get to the media, it's the sign that we have tremendous sadness for scavenging someone lower, deeper, more muddy than we do."

“If you’re the creator of a machist joke, you’ll have more opportunities to find out what you’ve created,” Anduaga says, “but if you’re a simple recipient, as it’s hard to control the effect of humor – to make you laugh – you may be able to make grace.” The question is whether you decide to continue expanding the joke or let it go off as it is, knowing what speech it reproduces. “We should think about why grace has made us, because it shows that we have assimilated more than we believe in different beliefs, social discourses...”

“What a society, what a mood,” says Aranbarri. “Humor runs along the rails of the structures that have been forged in society over the centuries. Repeating what is repeated, through humor the position in the pyramid is consolidated, through accepted laughter the daily structure is shaped, the foundations of society are reinforced”. And so it goes on to talk about the television series Aída to which we referred in the preamble: “If even in the conversations between good friends, those who came from South America to work among us have become machu pichu (outbreak, don’t take everything so seriously! ), it is not for a wonderful spark, but because a private television broadcast in Spain, not long ago, opened it to the hartazgo.”

'Women and humor' Beatriz Egizabal, in the Women and Humor workshop, talks about the position of women in humor and their ways of laughing at oneself. It follows from the interview conducted by the Portal de Tolosaldea (27-09-2017): “There are power relationships and, of course, it’s not the same to make a joke about the oppressor’s begging than to do the opposite. Everyone chooses where they stand, where they slide. And it’s not an accusation, but you also have to pay attention to that, because humor can be very oppressive, but also very transformative and revolutionary (…) Combining humor and beauty is not easy, if you don’t blur a bit. There are some limitations, but the use of humor can be a strategy for those who are less likely to occupy the public space”. On the other hand, Ane Labaka presented last year a research work on humor(s) in Bertsolarism from a gender perspective, focusing on interviews with 11 women. We have taken these words from the interviews made to him by the newspaper Berria: “In marginal areas he laughs himself much more than in the hegemonic plazas. I’ve seen the Bertsolaris go to the audience and sing about the fact that they have fallen breasts to older women, but before you sing with your chest, and as you also enter into the interior, by identification, the others laugh, and the power relationship is much more similar.” |

The humor between equals cries

Although there is a hegemonic humor, Anduaga explains that the poles have spread. “There are more sources and the speeches are more varied, partly thanks to social networks; even though the sword of Damocles is always on top, as censorship and as punishment. I find it wonderful that magma exists in the non-public spheres, in the gaztetxes, in the bars or in the parties of small towns. Based on trust between equals, a special humor is created, more plural in the speeches and with a great tendency to self-criticism (laughing at oneself). Through humor you can rethink yourself and transform things, I see a rich political action behind that. Another thing is if those speeches can be brought to the public sphere, knowing that this can act against you. If self-humor is to be done honestly, the power relationship has to be paritarian; everything else is hierarchical.”

As the “politically incorrect” discourse moves to the public sphere and demoralizes hierarchies, we want those artedramas in Euskera that unify those freedoms, theater and dance.

----------------------------------

Kamila Gratien

“We try to give what to think through humor and uncover contradictions”

Fun is totally tied to carnivals. It is a game that announces the arrival of spring, which merges theater, dance and verses; body expression and word; humor and criticism; local and beyond stories. On the other hand, the pockets (dancers) are thinner, more elegant, they represent a spring that will break the winter. We've been with a sense of shame, with Kamila Gratien Garazi, with whom we've talked about the creative process of Donibane Garazi's release and the peculiarities of his outdoor performance.

A fortnight of young people between the ages of 16 and 30, neighbours of Garazi, have taken part in the show. Although they are held on Carnival Sunday (this year on 11 February), preparatory work begins four to five months earlier. “The first thing we did was meet in October,” Gratien tells us. “We started to blur all those who went through the year, especially to Garazi, because it’s really garaztarra, but we’ve also gone further. This year, for example, the peace process had to be forcibly named, and also some international ones that affect us. But the divertiment is quite local.” In spite of the fact that it is the same, there are different ones from Garazi, Amikuze, Banka, Donapaleu, Baiona or Aldude.

The peace process, the demonstration in favor of political prisoners in Paris, disarmament, sexual abuse in the Church, the educational system, the festival Euskal Herria Zuzenean… all of this has touched (perhaps it would be more correct to say “shake”) the diversions during these years, also the themes of the time, the events in the mountains around, the stories among the peasants and, to highlight a theme, the issue of the Garonixe The residence, which was purchased in July of last year, became the gaztetxe, the most touristic area of the town, and the miserable, almost all of them back from gaztetxe, have taken advantage of to laugh at themselves, being from Garazi “the first capitalist gaztetxe of Euskal Herria,” explains Gratien with a smile.

But let's go back to the training process. Once the themes were listed, divided into groups of four or five people, they began to improvise without thinking about it too much, and from there they wrote the text of the work. The Bajonavarro writer and playwright Antton Luku has been his travelling companion, an essential reference to understand the recovery of diversions.

They all write games. Gratien tells us that it is very enriching to know each other's vision, discuss them and conciliate the discourse. “Libertinage is really the value of youth. It's not just fun. It’s true that with a smile people are drawn to it and it brings warmth, but it’s also denounced.” Asked whether the criticisms have behaved entirely freely when blowing, he replied that in the divertiment it is precisely “normal free” and leaves aside the shame. “Perhaps, because we are young, and it’s related to innocence, some things get passed more quickly. That is true, we are firmly committed to what we do, we have done it. Then we save ourselves a bit because we are talking about the stake, because it is theatre…”.

Truffle in all directions

Gratien has been libertying for four years, and told us that the issues related to the Basque conflict were becoming "safe". “It is true that this year it was quite easy to represent, to disarm, in a sense, it was a theater; bo, you understand me…” [yes, yes, I understand you, and certainly readers too]. They also address closer issues, as mentioned above: “Stories of the mountain, for example, that a farmer has seen the wolf, discussions about the land… We are not all of that world, although there are children of labourers; it is very enriching that we all participate in the process.”

The game of feminism has set us as an example: “Just as we have mocked Jean-Jaques Lasserre [president of the Council of the Department of Pau], because of the cynical jokes he often makes, we have also laughed a little bit about feminism, in the face of the contradictions he may have.” This does not mean, much less, that they have made macho jokes, but that the work of improvisation around feminism serves to reflect on the subject and to make known the discourse that can be given to the viewer, even if it does so from humor (from self-parody).

No machista jokes. We have taken this opportunity to ask you whether you think humor can be done about anything. “I don’t know how to think about that, you can laugh at everything, without taboos, but those things don’t make me smile personally. For me, when the discourse reflects top-down power relations, it's not humor." Gratien says humor is not necessarily related to smiling. “With freedom we also try to give people what to think through humor, uncover contradictions... The truffle is not always done in the same direction, around the same people; we change meaning, first over the neighbor, then over ourselves… All the issues we mention in the exercise of freedom are political and that is why we bring them to the plaza in all its crudety; through humor it is true that people become an accomplice of force”.

Crudely, but not immediately. “Synopsis often doesn’t say things clearly.” It is a task of the two bertsolaris participating in the show, who have to explain to the spectator what the actors are denouncing. Gratien tells us about the value of Metaphor, to return to the name of Antton Luku. Not in vain. The playwright has written a session on Libertentism (Pamiela, 2014) in which he criticizes, among other things, the words of researcher Nicole Lougarot about Sulatine masks because, in his opinion, he does not take into account the fundamental characteristics of our tradition, such as “chincheria”. This is what Xabier Etxabe, a dance expert, says in the written review of Luku's book Dantzan.eus, 29-01-2015): “Joviality is a humor, yes, but it seeks complicity through the ‘hint’. The joke shows us that there is no taboo, that you can laugh at everything (…) It is the laughter of the poor; what Bertsolaris have often used.”

“I can’t do theater with theory, I do it with metaphors, giving very short, concise and powerful slogans,” Lukuk said in an interview published by ARGIA magazine (No. 2,415). Etxabe also: “Metaphor demands to believe in the same poetic background, to think that there is a Basque country, that the Basque country forms a community and that there is a Basque theatre. (…) Lukuk aims at works created in Euskera and for the Basques, completely departing from the tourist shows held in Iparralde”. On the other hand, the Bajonavarro playwright said in ARGIA: “The characters arise if there are contradictory approaches between players, one defends one thing and another defends one thing. That's the essence of the tobe, that's what conditions good theater. We have to see the conflict, the forces of one against the other. The actor needs power to defend the characters. Each character has to be given its charm, otherwise we stay in parody or in pure criticism.”

Busti, Blai, H28…

According to Kamila Gratien, libertinage is a “magnificent tool” and “safe” that can also be done in the south. “The strength of the process of creation and improvisation, the freshness… is the most beautiful experience I have had in my life. I am convinced that we all need to live it. You also realize that it’s great to know the Basque.” From Euskera to Euskera. “We also reliably used the Basque translations of French words and expressions, and we spread through the Basque language in the divertimento, we have been very aware of it.”

Gratien was also the host of the Busti television programme, and he told us that there they were also looking at whether they were translating into the Basque language some of the originally French expressions or whether they were creating something of their own. “We have our values and our ideas, Euskal Herria is everything for us… and humor we did from there.” On March 4, 2015, Busti was released, a project created by the public television Kanaldude and the EhKz communication project, carried out by young people. They combined “more serious” content with humor, “lightening a bit” the issue thanks to the smile.

In summer 2016, Busti interrupted his path, after nine programs issued (all visible in URL 1), but Blai was enthusiastically launched under Kanaldude and the web Topatu.eus. He was born on January 14, 2018, and also enters “serious” content with laughter. A humorous news story through the hole and double is an example.

Perhaps, with regard to television, mention should also be made, such as the TV3 satellite polònia in Catalunya, of Wazemank of ETB1 and its heirs, but to what extent they shatter the hegemonic humor about the Basques... It is true that in ETB2 you can find discourses that are not seen and that closer references are used for Vasco-speakers, but they have also been built on traditional clichés related to identity (rural world, dialects…). On the other hand, ETB1 will hardly address such thorny issues as that of the Spanish language, which have to do with politics or the economy.

Perhaps, if you see somewhere the relationship (or the clash) between humor and politics (power relations), apart from some accounts such as Twitter or the Basque Radio Gerrenaplat program, you see it in the satirical publications and in the graphic strips of the press, to the extent that they necessarily have to deal with everyday (almost). Among the journals, we find in the neighborhood, for example: Charlie Hebdo, Le Canard enchaîné, Thursday or Mongolia. In our case, but in Spanish, TMEO is probably the best known, although there are others, such as La Gallina Vasca or Karma. Until recently there also existed in Euskera, a monthly H28 magazine that separated the blows to the right and left and that helped many vasco-speakers to enjoy; but unfortunately, it was she who cut off the road and today the press is the only breathing zone in Euskera.

-------------------------------------------------

Patxi Huarte Zaldieroa

“My intention is to question the discourse of power”

Patxi Huarte Zaldieroa is one of the comic book artists collected by H28 satirical magazines. On the pages of the newspaper Berria you will find its graphic strips under the motto De Rerum Natura; also Oiga! or in the Rainbow magazines. Many of us have the habit of stretching the newspaper first by taking it.

Do you feel calmer when you bring the Basque conflict to comic strips, let’s say that 8-10 years ago (before ETA broke its activity)?

Yes and no, self-censorship is still there, we live under the Spanish National Audience, you know. Long ago I decided to give my opinion to make my job more comfortable and ready. I mean, I wasn't going to liaise making jokes. I don't use humor every day, and for some seasons, like in the most severe crises, it's been completely gone. I am referring to the economic crisis and the crises of violence.

What should be the objective of political satire?

Assume 100% freedom of expression.

Should the draftsman stimulate power?

We cartoonists are demagogues, we highlight some things and others hide them because we have to simplify them. I would say that my intention is always to question the discourse of power, to show that there are other looks to look at things. In my opinion, it is the task of satirical cartoonists to question their powers, their supposed “legitimacy”, and when they are not clear about it.

Do you feel free to draw? Is there tobacco? It may be ETA, but you have drawn "natural" to your eaters...

Yes, it is many years and in that sense I feel free and secure, like Evax. I drew my peers and colleagues, because it seems to me that they are people and not the “demoniyus” that they have sold us. But there were also person icons. It's a mess. I drew them with the hood as well as they slept.

In most cases, the graphic strips of the periodicals have been a complement to the editorial lines taken by each medium. Is this how you perceive the "Nature of Rerum" or is it totally autonomous? His drawings usually appear in the opinion section...

Frankly, at first my tapes, you don't ask me why, they were scattered around, they demanded a special search. I often thought: “They haven’t published today!” For me I was pretty. Nobody knew where they were. Then they took me to the pages of those who think and I lost my uniqueness, I became a simple Anjel Lertxundi or Miren Amuriza (snail). I am no longer a species! But no, it's not editorial either. There is no editorial group behind it.

What are the characteristics of the drawing compared to a satirical radio program?

That you have to be very precise, there's no room for many.

Is speaking in Basque a limit or an opportunity for you? Or, quite simply, it's just one more and a half language.

I think it would be more successful in Spanish. They're just numbers. But I'm an Euskera militant, that's right. However, I recently received an invitation to participate in a project, in Spanish, and perhaps I can do something in that language. I had to say I'm bilingual, but no, I'm the polyglot!

Some character especially hard to take to comic strips? And do you draw easily? In the case of Urkullu you use a photo of yourself…

I'm not a cartoonist. I had to add “good”, but neither “cartoonist”, I am not. I tried it with Urkullu, but in the end I saw that his photo was stronger. Then I did the same with Otegi, what a mess! Obviously in Berria I was not forced to participate in a drawing opposition, it was all by plug.

When we talk about the "working" humor, we often talk about "incongruity", in places and situations that do not correspond to the characters. Is there a connection between that incongruity and surrealism that often reflects your drawings?

Yes, at the base of humor there are illogical and surprising ties. I like to draw those weird links, like an anchovy talking to a refrigerator.

---------------------------------------

Joseba Larratxe

"Exaggerating the usual absurd point of reality is the way to make humor"

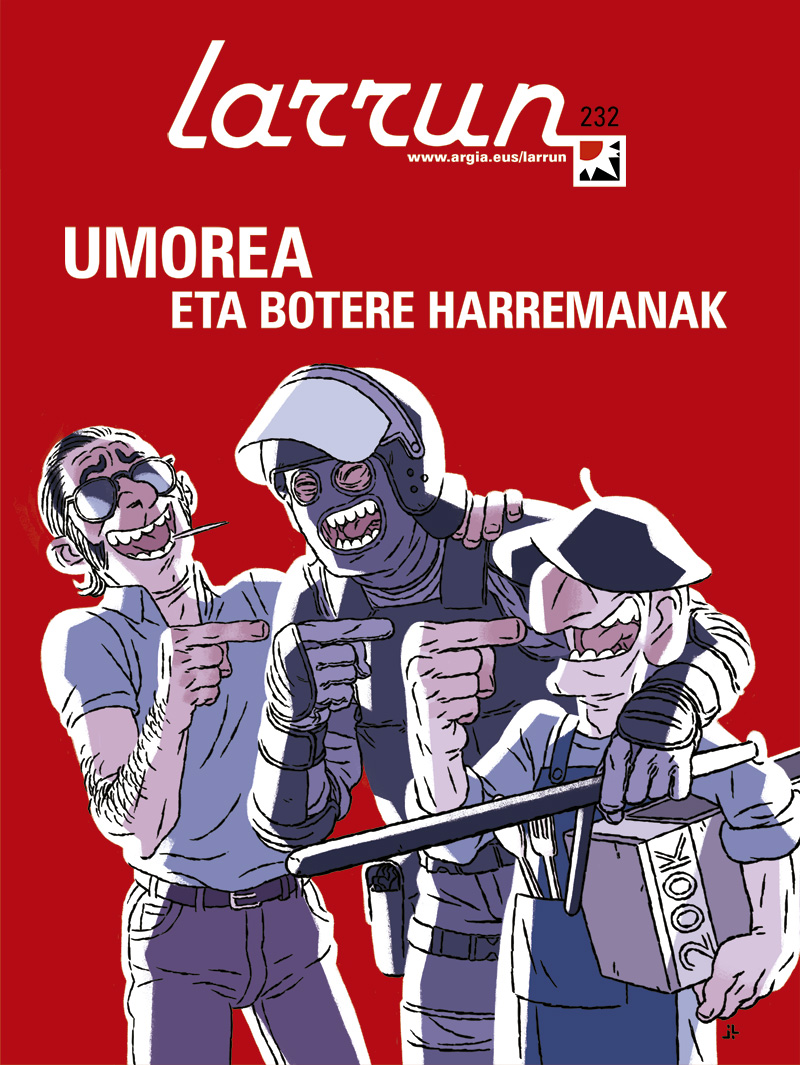

We had to close this LARRUN with the words of Patxi Huarte Zaldieroa, but we decided to extend a couple of questions to the Irish Joseba Larratxe, a H28 collaborator. He has made the shadow illustration, after the author of the report has proposed some changes to the original drawing, which was "too explicit". The draftsman seems more daring.

Are you worried -- fear -- about drawing? Is there self-censorship?

I have not been afraid of the cases of repression of the Moorish Law that we have seen lately. But I recognize that publishing in Euskera and in small media (H28) has given me a lot of freedom to draw what I wanted, I knew it was very difficult to know that the one who was in the focus of criticism had criticized it. On one of the few occasions when I've done self-censorship, it's been for other reasons. For example, a tape that I came up with for H28 didn't draw it because it seemed to me that I could be a male chauvinist.

The case of the young people of Alsasua is red alive,... How do you make humor about them? What does the interior ask you for on those occasions?

I don't think it's a conscious decision, but I think most of the humor ribbons that I've drawn were centered around the present. Unfortunately, today is full of shameful news, and I have therefore worked on those issues that concern me.

However serious they may be, they always have an absurd factor. In the case of Alsasua: if fifteen years ago we had been told that an altercation in the bar would be judged as terrorism, we would laugh and then cry. In such cases, the way to make humor is to emerge that absurd point by exaggerating. By denouncing you make a laugh and also make the reader reflect. The goal is to get a tape that meets those three things.

Attack on Charlie Hebdo Uxoa Anduaga in Jakin magazine: "The attack showed that the sense of humor is inescapable to the national issue. (...) In that racist satire of Charlie Hebdo, paradoxically, the discourse was ‘politically correct’, a transmission of humor consistent with the criteria defended by the French State. The attack, therefore, only increased the social legitimacy of that sense of humor – and of discourse – by stating that what Charlie Hebdo was doing was humor – not insult – and that if he was French, it was necessary to be in favour of it as a matter of few alternatives (...) Accepted, announced, subsidised or consumed massively conserve the national culture under a state of state.” |