"You have to know Spanish to understand the unified Basque"

- Here's a book in Baiona: The Basque of Senpere (and Lapurdi) in the 18th century (Lapurdi 1609). Pulling the thread, we've met a tolosarra who lived at the time of the founding of ETA. It is usually said “here, here the ones here”, but from here to there is Xabier Elosegi.

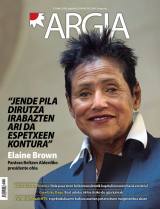

Gerra garaian jaioa, euskara gauza ezkutukoa zen Tolosako herriko kaleetan. Euskaltzale da gaztetandik, mendiak abertzaletua. ETAren sorrerako Ekin taldean zen, eta atxilotua 1961ean bertan, Donostian trena bidetik atera nahi izan zutenean, zenbait bandera espainol erre zituztenean. Martutenen izan zuten, eta Carabanchelen, Ipar Euskal Herrira betiko baino lehen. Bertan egin du bizia, lanean.

Your book starts from another book: Othoi çato etchera (Lapurdi, 2016). It’s just a letter that appears there…

Yes, that letter mentions: “Surely the tutelage here was heard, the cursed evador, prisoner of that day, in 1775, was brought to Paris by the tower of the Sabat Çena that someone killed him, and a month ago people took the road that that book has reached their etcherat Baignan…” It was a beautiful treasure, terrible. I set out to investigate. In the letters of Othoi çato etchera there are several names, among them those of Sara, and I knew them all, because I lived in Sara, and being there, I copied the whole file of the village. Eight thousand pages by death, marriage and baptism. So I had the theme of Sara, the house and the last names for four centuries (XVI-XIX). I started with Sara, but then I followed by Azkain, and Ahetze, and… And I hit myself in that forgetfulness, seeing that it had been a crime in Ahetze. I expected it to be documented, but no, the only reference to crime was that letter, written by my father to my son. To conduct this inquiry, I walked into a notary's room.

What a notary?

MARTIN Harismendy. I wanted to find something about crime, and in the research I found a lot of things, including documents in Euskera. I contacted Xarles Videgain, Euskaltzaindia, and she found it very nice. Xarles, happy. In another statement I found: “The observation made by Sabat de Behotaz at Betrikoene’s house has been exalted and estimated, in Joannis de Hirigoyen, Donibane and Bernat de Goihetche Senpere, which have already been made in that house that has been said, and which still has to be done, because it has to bring a flooded house and a recessed house. It's also rich in dictionaries, because people used words that are now lost. And so, I got really stuck at work.

This has been said in the documents of notary Martin Harismendy.

He started in 1741 and worked until 1779. That Harismendy was from Arbona, a large house, who married a daughter from the big house. It's 13,167 pages in his file, and I started seeing them all one by one, to see if I found something special. Most are in French, although there are 164 pages in Basque. In addition to Harismendy's documents, I've researched the files of other notaries. Documents are always in French, but inside they contain annexes that are called “linked to the Minutes”. They do not translate the document itself, they create another document, and in some cases, that annex is essential in Basque, because without it you cannot understand the record in French.

What do you think it shows?

Society was monolingual vascoparlant, and as for nobility, there are amazing cases. In 2012, Gervasio di César and Kike Fernández de Pinedo published an interesting work in the journal Fontes [Linguae Vasconum], in which they analyzed the case of Mari Ochoa de Villanueva from a noble family of Salvatierra (Álava), based on a document of 1571, saying that for the girl to understand a power sent by her father she had to be a translator. In Lapurdi, around the middle of the 18th century, the linguistic customs within the nobility were not only French. Not everyone, at least. Some nobles were Basque monolinguals. In Sara, in 1741, we found the case of Mari Ochoa in the Lehetea family, one of the great nobles of Lapurdi until the 19th century.

It contains various documents: debts and cancellations, expert reports, budgets, inventories, wills, marriage covenants, on the management of the Senpere forests… all that is mentioned in these documents.

Yes. In our opinion, this corpus shows a new perspective on Basque linguistics. And certainly the people's. The use of the written Basque is broad and varied, and in some way it is assumed by all the notaries: the notary himself attaches numerous documents to the document itself, saying “annexé au present acte”. Similar observations are frequently made in official documents.

What do you say about Euskera in those documents?

Euskera is a forced language in many writings. It is the Frenchman who forces it, no doubt. These texts in Basque are full of calcos, but today’s Basque himself is full of calcos. Yesterday I was in the House of the People of Baiona and there is a metal plate on the building. The text is in French and there are four translations. In Basque he says: “Today, it still houses the theater and the house of the people.” It is a disgrace! The natives would simply say: “This building continues to house the theater and municipal administrative services.”

When we talk about Kalko, what do we have in Basque “batua”? Everything goes on. It is used to pay “continue” in Spanish anywhere: “Two are still on the run,” the passage is not understandable to most of those here.”

You also criticise Euskera batua, as you wrote here and there.

The current Basque “batua” is full of Spain. You have to know Spanish to understand the unified Basque. That’s what I wrote 31 by the hand on the blog and I all said yes, I was right, but then… The written Basque is pretty good, although there are big petals. But most people don't read Euskera written. People listen to the Basque of speakers and participants in the debates. And I'm talking about the national media. The Calcos of Spanish expressions are increasingly being used, and Euskaltzaindia does not say anything about it. And the people here, forgetting the local Basque, copying what is said “unified”! To miss a leg, to touch, it’s going to cost you the sun, it’s worth it… That’s not Basque, that’s Spanish, Calco, and the people here don’t understand it.

When you were young, in Tolosa, were there any concerns about Euskera?

We spoke Spanish at home. The mother did not know it, since it had been founded in Argentina. My father always spoke to us in Basque and spent the summer in Leaburu, Goiatz, Gaztelu or in a small town around. There, the whole of society was speaking in Basque. Euskera has been the second language. Beloved, always. I remember that in 1947, at the age of 10, Father Kulixka came with a book from the series: “A book has come out in Basque!” Then, on my own, I paid Euzko Gogoa's subscription. We picked it up at home…

Euskaltzalea zu.

Always. When Orixe [Nicolás Ormaetxea] made the Mass Book, I bought it. Ha, ha… So I was very believer. I bought it, but Uncle Jesus paid me. He was Euskaltzale and Abertzale, as well as his wife, who always spoke in Euskera. In Tolosa there was a Basque atmosphere, but it was not evident. There were some sites around Anjelatxo Arrue, for example, as Anjelatxo moved theater with his daughter Mirentxu Moraiz. Another place was the Cordimarians, the Hunters. They had the parish and brought out the choir of Santa Águeda every year, Santa Águeda made by men, not by children. I had an impression. Moreover, it was not heard in the street more than a crew. And in our crew, another friend and I were talking about Euskera, almost clandestine.

Clandestine in the crew?

The crew was working in Spanish, but we always talked about two or three in Euskera among us, when we could.

You soon became part of an Abertzale society.

In 1957-58, when I entered Ekin, where he became ETA, I didn't even know what the Abertzale word was. I was Euskaltzale, I came to nationalism through Vasquism. Once I entered a closed circle, the one who took me there did not know Euskera, and it gave me anger. He was politicized, but he didn't know Euskera. It was a contradiction, and it still contradicts me.

First, Félix Arrieta was arrested. On 18 July 1961, together with the sabotage of the railway in Añorga, the Spanish flags were burned in Donostia-San Sebastián.

It was an order, if arrested, for the prisoners to stay for two days in the situation so that the others would escape their homes. Felix held her back, but in vain, no one left out of the house. Kar, kar… Felix [Arrieta] was captured on July 18, and I, at the end of July or the first of August. The cops arrived at my house with Julio Eyara, head of the municipal police of Tolosa. He brought them to our house. It was said that I was a friend of my father. Before I was in Martutene, then in Carabanchel, next to several: Imanol Laspiur, Serafin Basauri, Rafa Albisu, Julen Madariaga, Olaskoaga…

What do you say about torture?

Felix was a great hunter, and Imanol Laspiur, another of the great protagonists of the day. I saw Imanol blackened. I had been caught from the last ones, and when I got to Carabanchel, I had a broken leg. Before we entered the prison and were confused with all the prisoners, the newcomers had us apart and Pontxo Iriarte, Agirre, López de Lacalle and I were together. We were the last incarcerated, with whom I wasn't treated before I went to jail. Except for Iñaki Larramendi.

When did Carabanchel leave?

Early January 1962. The then Franco was, in a way, naif. The seven members of Carabanchel were tried in the trial known as “sumarisimos” and sentenced to great sorrow: Rafa Albisu, 20 years in prison, and Iñaki Larramendi, 10. But for example, Larramendi was released in 1964.

Were they from ETA?

Since 1961, yes. Until then we had seen ourselves surrounded by fog. A shadow, a zarauztarra, comes to my mind. They were fighting not to come with us. Some knew that there was more than one branch among the Abertzales. I would say that in 1960 things were clear. When I left jail and came to this side in 1962, we were half a dozen escapes, no more, and I was from ETA, there's no question. I arrived in the summer and worked in the fall at Hazparne School. I've always worked. But I've also met those who have never worked in life. I do not know how they have lived without working for years and years and without learning Basque. I don't know how life can happen. It's not the majority, but there are some.

What reading did you make of the end of ETA?

I read a long time ago. I did not agree with the murder of Miguel Ángel Blanco. It was a terrible blow. But it had already been a terrible blow [Anjel] to kill Berazadi in 1976. Or kill camels without tests. Just like spies. They weren't either betrayals. The death of Yoyes. The organization has always given explanations, everything has been explained, everything, but they do not serve. For me, no. And not just for me. Order multiple actions. Prisoners are not terrorists, but they have committed terrorist acts, those nationalists, those gudaris, have done things that should not be done. I don't care, don't you have to account for Euskal Herria?

What do you now say about the attitude of the governments of Spain and France, together with the end of ETA, to apologise to each other?

Spain and France want to destroy Euskal Herria, making the Basque disappear. There is no doubt. History shows it. To do so, they will use whatever it is. Do you want to apologise now? That's what you have to do. Some have done so and others have not. I think it is a gift of the person, both positions are acceptable to me.

“Oso bortitza da Baionan bizitzea. Ez da euskara entzuten, ez bada gurea, edo gure ingurukoa. Badira abertzaleak, zeintzuek esaten duten behar genukeela abandonatu Baiona Euskal Herria den ideia. Behar dugu onartu: ‘Baiona ez da Euskal Herria’. Ez dut berdin pentsatzen, baina konprenitzen dut jende horien pentsamoldea”.

“Jakin nahiko nuke Hegoaldetik heldu den jendeak muga pasatu eta non uzten duen euskara. Hemen espainolez ari dira. Orain hogei urte ez zen horrela. Euskararen aldeko harrotasun handiagoa zen orduan. 1976an Tolosara itzuli nintzelarik lehen aldiz, jende askok egiten zuen euskaraz, eta harriturik nintzen. Berpizte bat izan zen. Orain ez dut horrelako ilusiorik topatzen, nahiz eta nire gazte denboran baino askoz euskara gehiago entzuten den Tolosan”.

“Badut ezagun bat, flandriarra, polizia komisarioa izana Bruselan. Frantsesez egina du bere bizitza guzia, baita haren emazteak ere. Orain erraten du urtetik urtera zailtasun gehiago duela frantsesez egiteko. Zendako? Ez du behar! Erretretan dago, Flandrian bizi da, flandriera baizik ez du mintzo jendeak, flandriera du bere hizkuntza bakarra. Hemen noizbait horrela gerta baledi, kontent ginateke!”.

The Basque country has multiple facets in the field of the situation or status (in the use of the street, in the home, in the administration, in the literature, in the media, in the situation of the dialects, in the degree of learning of the immigrants...) and in the field of... [+]