"The need to go through Spanish for the internationalization of the Basque literature is recognized"

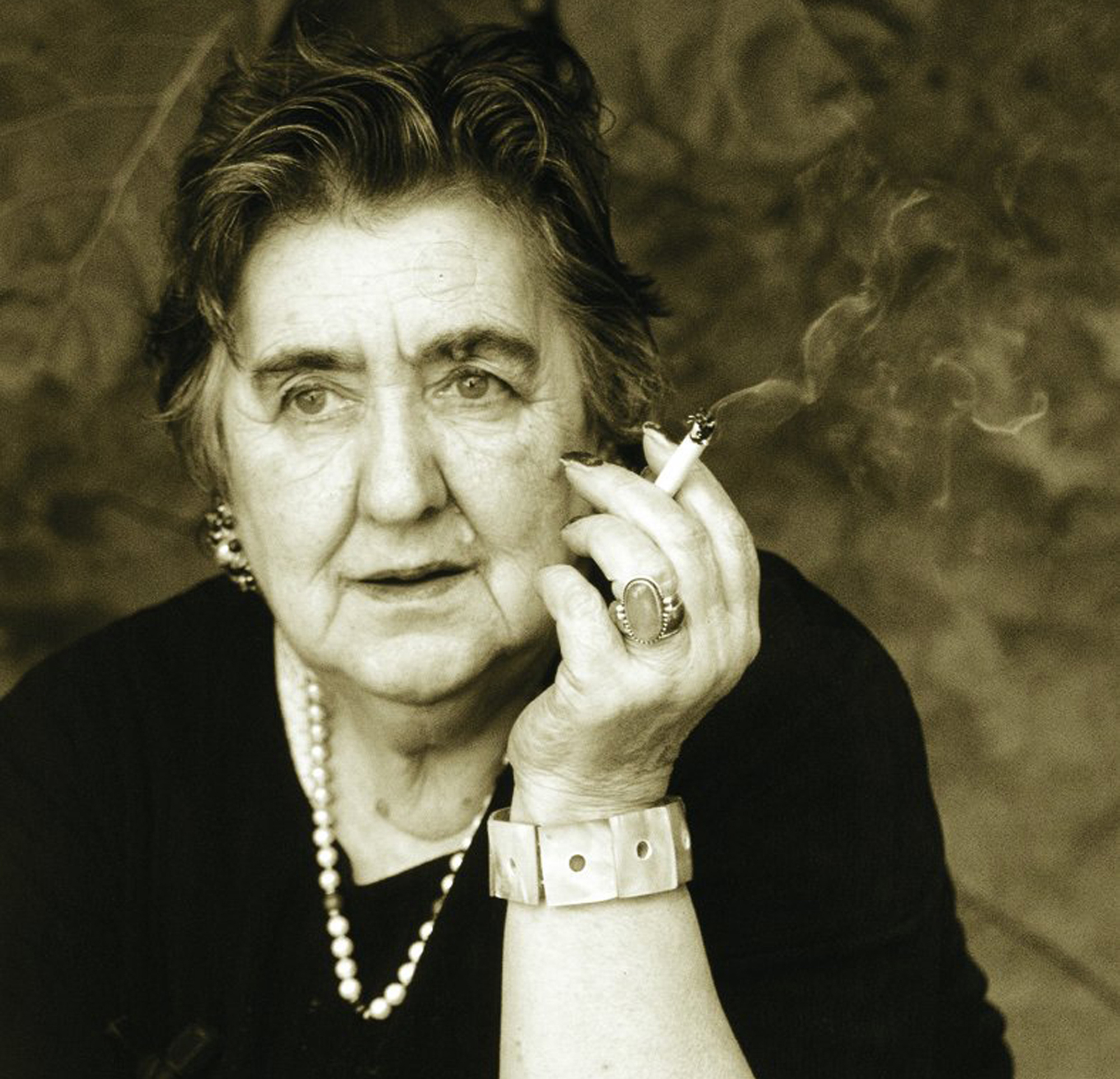

- Garazi Arrula began to investigate self-translation practices in the Basque Country based on three factors: on the one hand, because more and more Basque writers were starting to translate their works into Spanish or French; on the other, because our socio-linguistic situation worried him; and, finally, because he loved literature. If you've read the self-translation and the question has arisen, if we're talking about google translator or what we're talking about, this is your reading.

Magisteritza eta itzulpengintza ikasia, Euskal Herriko autoitzulpenaren inguruko doktore-tesia aurkeztu berri du, Ibon Uribarri Zenekortaren zuzendaritzapean. Besteak beste, Amélie Nothomb eta Anaïs Nin-enak ekarri ditu euskarara, eta iragan urrian argitaratu zuen estreinako ipuin-liburua: Gu orduko hauek (Txalaparta). Orain, langabezian dago.

You just finished your thesis: “Theory and practice of self-translation in the Basque Country”. What is self-translation?

In short, self-translation is to give one's own speech, a pre-existing text, either oral or written, in another language, dialect or linguistic variant.

And what did you look at?

On the one hand, I have analyzed self-translation in its breadth, as a practice, as a widespread practice that we Basques do on a daily basis. On the other hand, I have focused on literature and analyzed the discourse that Basque writers have translated their work in Spanish with respect to practice and how they behave when translating their texts.

How have you studied it?

To begin with, I've chosen a work of ten writers: Northern Rio de Aurelia Arkotxa, 100% Basque de Itxaro Borda, The mouth of Harkaitz Cano, the tram from Unai Elorriaga to the SP, Tigre Ehizan de Aingeru Epaltza, The hands of the Mother of Karmrodriguez ele Jaio, A glass eye of Miren Agur.

Why those ten?

As it is the first examination, I wanted, as far as possible, to take the self-translation of the Basque Country perfectly. These ten are contemporary, prose, and represent the whole geography of the Basque Country. For example, from a gender point of view, it's not a reflection of reality, because I've chosen more women than men, but I've done that on purpose. In general, it is a varied and representative sample.

And once elected?

I have received fourteen self-translations of these ten works – four out of ten have two self-translations, one published in the Basque Country and one outside the Basque Country. I have compared the translations and those of Euskera, and for that I have looked at two things: on the one hand, I have looked at how cultural references relating to national identity have been given, for example, how the Basque, Basque or Euskal Herria terms have been translated, always bearing in mind the context. Then, I analyzed how other languages are cited in the Basque texts and how they are mentioned in the Spanish texts, and some conclusions of this type ditut.Tesi cannot be analyzed 24 very detailed texts, so I made that selection thinking that it would be quite representative.

At first you had the suspicion that literary self-translation was not a marginal or exceptional practice. Confirm your suspicions.

The preparation of the catalogue has been an important part of the thesis. I have departed from the catalog of the Return to Basque Literature made by Elizabete Manterola. It included all the translations made from the Basque language: those made by another person, those made in collaboration and self-translations. I have updated and completed the list of self-translations to have a basis and an overview. Thanks to the catalog it has been seen that self-translation is a widespread practice in our small, since until 2015 I have compiled 325 titles and 125 self-translators, that is, more than one author has self-translated several of his works.

Would it give some general characteristics of this production?

Child and youth literature is the majority self-regulation in terms of gender and we can say that one of the reasons could be that state publishers have agreements with each other. Eight out of ten books have been self-translated into Spanish. There is therefore a great imbalance between French and Spanish. As regards bilingual or multilingual editions, the difference between the main languages decreases slightly. Another significant fact is that most self-translations, more than half, have been published in the Basque Country. Regarding chronology, it is in the last three decades that more self-translations have been published.

You say that self-translation is translation. Do you think otherwise?

Yes. In the self-translations, the editors, the press and the authors insist that what is being translated is not a translation but a version, or an adaptation, or a rewriting… This is always justified by saying that they have made adaptations to the text, but not only in the translations, but also take advantage of the reeditions to introduce changes, as verified by researcher Mikel Ayerbe.

In addition, the translation practice itself necessarily involves adaptations. Functionalism has shown that there is a tendency in the translation to adapt the text to the culture or to the objective reader, although it is not so evident in the literature, since the activity has a great symbolic value. It is quite unfounded to deny that self-translations are translations, on the grounds that adjustments have been made to them. Behind this is the idea that translation is literal. I think there is a lack of knowledge behind this reasoning; that is why other terms are being sought.

There are other factors, of course: commercially it is more convenient to say that self-translation is a second original, or a Spanish version, than to say that it is a translation. The Spanish system, for example, prefers self-translations because, on the one hand, they are more profitable, but also because it responds to a concrete logic.

What is the logic of that?

On the one hand, the translation still has a negative tint, and even more so when it comes to Euskera, it seems that it raises more uncertainty. On the other hand, there is a desire for assimilation. The Spanish literary system has a centripetal force and wants the works produced in peripheral languages to be translated into the hegemonic language and preferably made through self-translation, to be a second original and to function as an original. This entails the risks of any assimilation, and the expression of Basque identity or not is often left to the content. In this sense, I suggest in my thesis that the Basque system reproduces that centripetal force of Spain. Self-translation is driven by public money, either by the delivery of an extra amount in the translation awards, either by the purchase of specimens or through scholarships. Perhaps other forms of translation could be promoted, such as that of minority languages; today, the need to move to the world in Spanish is recognized.

Does the French system also do so?

No, and that does not mean that it is better, because at least Spain wants to assimilate it, confesses that there is a Basque literature that wants to be integrated into it, while in the French State translations have always occupied a very peripheral place, and minority languages are not recognized, there is a greater contempt. The small number of books in Basque translated into French is very significant.

There is no author who has decided to translate himself.

Yes, and our context gives all the conditions for self-refoulement, so I think this option is very important. There are those who find it uncomfortable, both self-translation and translation itself, for example, Joxe Azurmendi. She understands the national construction from language and culture, wants to dedicate her texts to the Basque world, so we can understand her decision in this context, whether or not I agree. On the other hand, Uxue Alberdi, for example, said that she is considered a Basque writer and that she does not feel comfortable writing in Spanish, even though she has been offered it. However, he does not deny that his work is returned by another person. In any case, there are more statements from self-translators than those who have not.

Why have self-translators translated?

On the one hand we can see personal motivations, for example, the desire to develop personal work in another language. Another personal motivation may be the desire to maintain authorship or control of the work; control is quite doubtful, but good. And in relation to this, mistrust towards the translator. But in other contexts, that's all gone, too -- it's not exclusive. There are also external factors, although personal and external are always related, but the “lack of translator” can be considered external – although there are more and more languages – money, time… It also has to do with professionalization: if you want to live from it, in most cases, there is no other way.

Why do you say that control is doubtful?

It seems that the authors are given more legitimacy, as they themselves have created that these works will be the most appropriate to translate that work, because they know what they have said. I have always said that they know what they meant, then another thing is what has remained on paper. On the other hand, this control is limited because we have seen what things the authors have been asked for. For example, Uxue Alberdi has told how Alfaguara offered him [The Game of Chairs] to self-translate, but they asked him to crop and adapt the book to public Spanish and to the trends of the literary system in Spanish. He didn't. Finally, the Spanish edition was edited by a Basque editorial, translated by Miren Agur Meabe.

Last year, you published a book of stories. Would it translate itself?

No. I would like to say that it is a political attitude, but it is not only that, because I do not have such an elaborate literary language in Spanish, and it also seems to me that today there are translators who do so. On the other hand, having conducted a study of this kind and seen the dependencies between systems, asymmetries, etc., I do not want to participate in this game.

If you turn, will we always be subjects?

The socio-linguistic situation of the language influences the practice of translation and translation. For example, it is not the same thing to return between French and English in Europe as in Québec. It does not have the same implications at all, and that is why I say that we must take into account the asymmetry between languages, and that all these complexities of a multilingual, peripheral and borderline culture such as ours must necessarily be taken into account when investigating translation or translation. I am not against the translation of Euskera, I believe that it must be translated from Euskera, clearly, and promoted, but always bearing in mind how it is done, and without falling into that assimilation, precisely because it is very easy for them to fall there. In short, the Basque literature systematically self-translates from subordinate to hegemonic language, and not the other way around.

How can we cope with this desire for assimilation?

You can position yourself at the discourse level. If you say clearly that Spanish is a translation, that means that there is already another text and that it has been created in another context and in another language, with all the implications and connotations that this entails. However, if you say that it is a version or a rewriting, of course there is an original text, but what is in the hegemonic language will always have a higher level, not only in the case of the Basque Country, but in all other asymmetric situations, because the adaptations in question never return to the Basque language or, in general, to the subordinate language.

You can then position yourself in the same text. Look at Agur Meabe, for example, wrote a glossary at the end of One Crystal Eye. That's a positioning, it makes it very clear that Spanish is a translation. The cultural transfer is very remarkable, as in fact the words appearing in the glossary are not so specific, and there was apparently no need to do so. I'm not going to say that now we're all going to make glossaries, it's just one way to avoid neutralization. In other translations, on the other hand, the terms associated with the origin have disappeared in Spanish, not so the references to the language: the Basque language appears even in those where there are no “needs” for it, and I have seen that the revelation of the Basque language can be a way to compensate for the neutralizations that are made in another way and to express the Basque social imaginary.

Idazten eta itzultzen, bietan aritzen direnei sarri galdetzen diete ea zer duten nahiago. Arrulak iskintxo egin dio bata ala bestea aukeratu beharrari: “Autoitzultzaileek identitate bikoitza daukatela eta halako zozokeriak esan ohi dira beti, oinarririk gabe eta argudiatu gabe. Gaur egun, gainera, hain onartua dago identitateen konplexutasuna eta etengabeko eraikuntza… Dikotomiatzat aurkezten dira maiz idaztea eta itzultzea, baina nik ez ditut hala ikusten. Bietan dago sortzailetza. Beraz, galdetuko balidate, horixe esanen nuke: sortzailea naizela”.

I have experienced two very different linguistic experiences in two southern peoples in recent weeks. One at a conference organized by a public institution of a Basque people and another at a school assembly. If we were at the conference more than 80 people, I would say that 90%... [+]

Ekain honetan hamar urte bete ditu Pasazaite argitaletxeak. Nazioarteko literatura euskarara ekartzen espezializatu den proiektuak urteurren hori baliatu du ateak itxiko dituela iragartzeko.

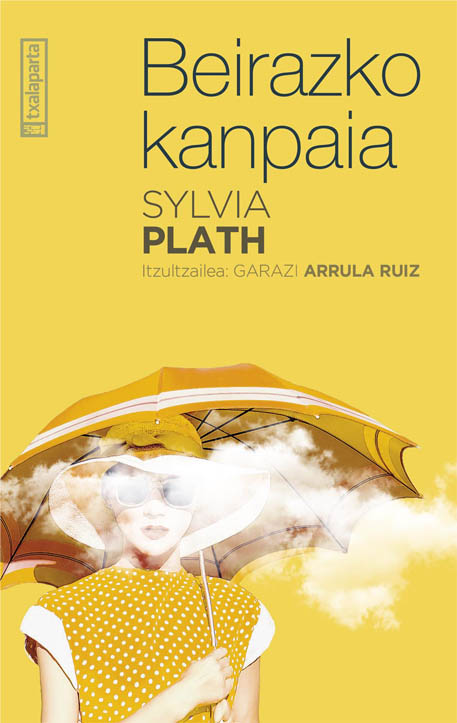

Many publishers rejected the book "The Glass Bell," because they understood it to be a barn and a bit light. It was first published in 1963 with the nickname Victoria Lucas. The glass bell could be a novel, but since it is a story very close to the author's life we could say that... [+]

Barrenetik zulatzen zaitut: 8 ahots itsasertzetik poesia antologia elebiduna argitaratu berri du Liberoamerika argitaletxeak. Ekuador, Mexiko eta Argentinako lau poeta eta Euskal Herriko lau itzultzaile elkartu dituzte. Martxoaren 30ean aurkeztuko dute jendaurrean.