Building Feminist Memory

- Now that the dissolution of ETA is very close in time, we have launched in Euskal Herria a renewed scenario regarding the conditions for resolving the consequences of the armed conflict. On the road to the closure of the cycle, there is still a long way to go: the return of prisoners and exiles and the recognition and reparation of all victims are pending.

What is more, the work is multiplying in this last aspect. In fact, as the intensity of a given violence decreases, other violence that sustains society emerges, as Emagine warned at the Feminist School of 2016. Sexual violence in the context of the political conflict in Euskal Herria is a clear example of this work that is multiplying us.

The tendency to use women's bodies as weapons of war in war contexts has been repeated throughout history. From Colombia to Bosnia-Herzegovina, through Chile, Ireland and so many other countries. The use of sexual violence against women has been one of the most powerful weapons in conflict contexts and Euskal Herria is no exception for anyone. Sexual violence against women has been present in all areas and forms, from internal violations to street violations. On this occasion, and based on the recognition of all victims, we will bring to the center a series of aggressions that the story of history has kept out in general, all of them suffered by women and related to each other.

The name of Ana Tere Barrueta and Mari Jose Bravo can help us to locate us, as we both have fatalities from those attacks. Ana Tere was raped and murdered at age 19 by members of the GAE (Spanish Armed Groups) police group in Loiu. Mari Jose, for her part, was raped and murdered in San Sebastian at the age of 16 by members of BVE (Spanish Basque Battalion), who also seriously injured her partner, dying eight years later for the damage caused by the beatings. The most tragic victims of a series of violations with political demands of the same modus operandi between 1977-1980 are Barrueta and Bravo, who, like the other raped women, have been left out of the official list of victims of the Ministry of the Interior. These cases, like most of the murders perpetrated by para-police groups, have not been prosecuted, and both aggressors and murderers have gone unpunished.

In the first part of the report prepared by the Social Forum on the unresolved cases that have left the conflicts in Euskal Herria, which has been limited to cases that have ended in death, Barrueta and Bravo have been recognized as victims of the conflict. One step further, in a report published by the human rights association Argituz the aggressions with political demands against women in the Basque Country are recognized for the first time and officially. According to the data provided by this association, politically motivated violations by far-right para-police groups were fourteen - in both cases leading to the death of the woman - and several cases have yet to be defined.

These attacks have been grouped by the same modus operandi used in the execution of the attacks and by their intensity over a period of time. Towards the end of 1977, the first violations with political demands occurred in Pamplona. Towards the end of 1979, they began to occur in Bizkaia and Gipuzkoa, in the latter territory the majorities that were located between Pasaia and Irun. The attacks were carried out in villages where political awareness was strong and thought out beforehand and strategically. In all the attacks, two or more aggressors participated, selected young victims, appeared armed and by car, raped victims after interrogation and then politically claimed violations, threatening more. The fact that the last point of the way of acting is a threat, as Argituz explains, shows that these attacks beyond the victims sought to “provoke terror in the different segments of society that shared sensitivity or rebellion against Basque nationalism”. To this end, and once again in history, they opted for the classical technique of using women as weapons of war.

Earth to sow fear of women's bodies

The anthropologist Begoña Aretxaga suggested with her studies that “the political violence exercised on the body and the body cannot be subtracted from the meaning of the sex difference”. In other words, political conflicts have gender. Olatz Harmful obeitia, a researcher in the field of political violence and the gender crossing, underlines this idea as context the case of Euskal Herria. In his study we can read that to persecute people they use their subordinate position in social relations, even in contexts of political conflict. As gender is one of the main vertebral societies, it becomes a significant aspect when it comes to pursuing a party in conflict situations.

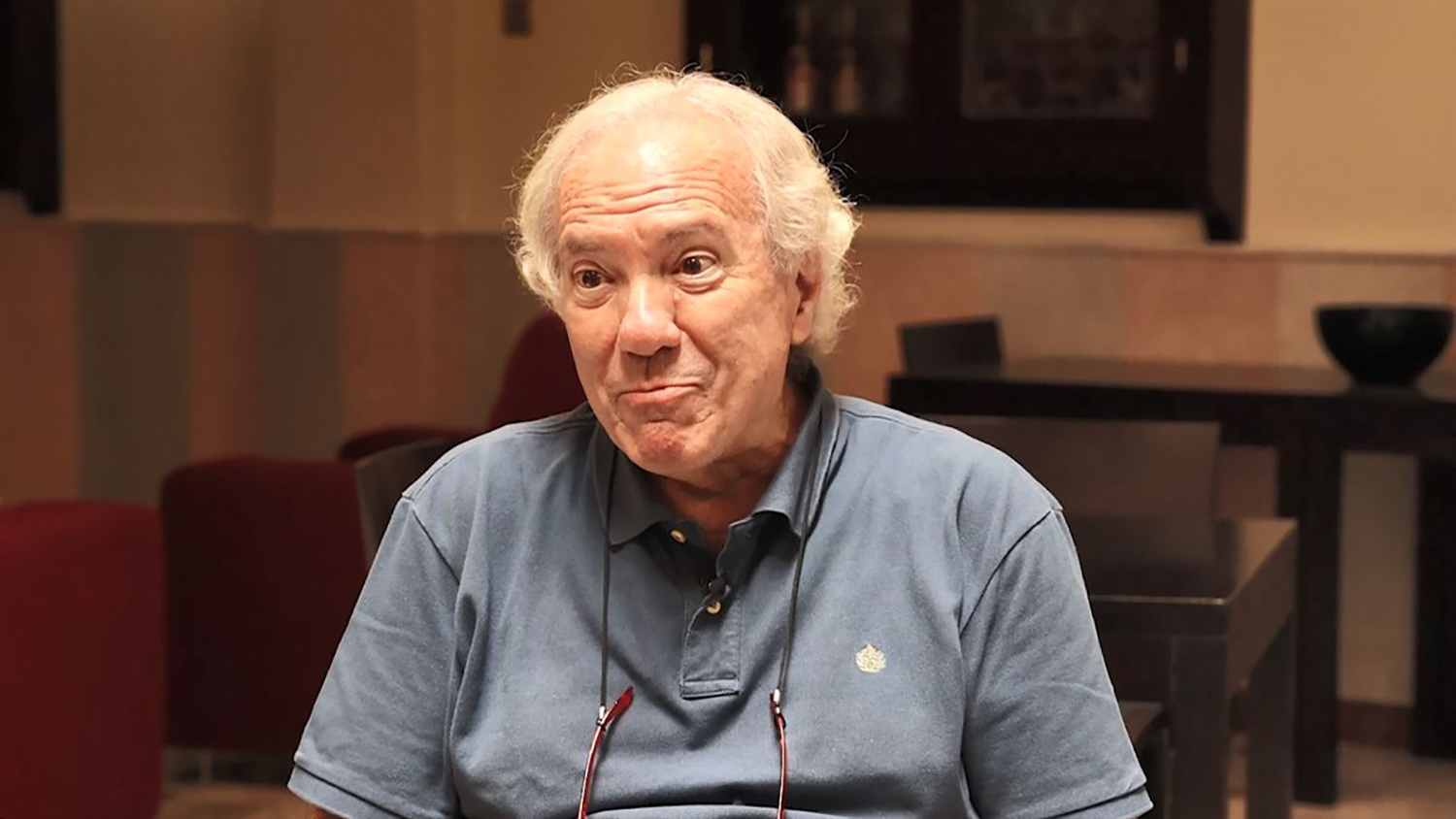

BEGOÑA ARETXAGA

“Political violence

over the body

and the body

cannot be subtracted from the meaning of

sexual

inequality”

“We could conclude that the attack on a particular persecuted body seeks to provoke fear throughout the whole social body or in a concrete community that surpasses it,” explains Harmful Beitia. When women are used and raped as weapons of war taking advantage of the subordinate position of the female condition on the condition of man, the aggressor seeks, through intimidation and threat, the obedience of a community or group of people.

At this point we find the use of the social construction of fear. Although fear is a fundamental emotion for survival and self-defense, its social construction seeks obedience. Injuobeitia emphasizes that things that may constitute a threat or risk are intimately linked to the condition of each person – class, race, ideology, age, gender or sex- and that fears are socially constructed about these conditions. Thus, we could conclude that the fear of gender violation that had been built with the use of women as weapons of war sought obedience and demobilization of an entire community or group that shared common ideas, values and practices.

Women abandon victim status

As the body of women was about to be a useful weapon in warfare, the threat of rape that sought to affect the entire community had a stronger impact on women. However, many women knew how to use fear as a fuel for mobilization in the face of paralysis, a clear example of this is the strong response of the feminist movement to violations in Orereta. Within the Memorandra group that works in the construction of the feminist memory of the locality, Eli Etxabeguren has worked in the construction of the historical account of the feminist response that these violations provoked in Orereta, which considers “a turning point and a great milestone in practice” the response of the feminist movement in the face of the event. Etxabeguren has valued women’s abilities to “overcome fear and transform it into alliance, fraternity, cohesion among women, powerful feminist discourse and struggle”.

Etxabeguren explains that it was difficult to make a gap between all the struggles in the people with the political discourse about the violations in the context in which daily murders occurred due to political conflict, since they had to fight from the female subject, in addition to parapolice groups and with the Spanish State, also with leftist social and political movements of the people. “This led to the empowerment of the feminist movement of the people,” he says. Among the actions carried out by the Women's Group of Errenteria is the Garraxi magazine, which was specifically edited to respond to the violations, the night demonstration to claim that the pickets, the night and the streets are also women, and the general strike called on 17 January 1980 to denounce the violations.

However, many women

knew how to use

fear as a fuel for mobilization

in the face

of paralysis, a

clear example of this is the strong response of

the

feminist movement to violations in Orereta.

Etxabeguren attaches great importance to the construction of memory because, in his words, it allows to continue creating new identities, taking steps and activating the feminist movement. The report of the sexual assaults she performs leaves blank the victimization that grants women the status of passive subjects, as she visualizes the women who are in their entirety active subjects. If psychologist Isabel Piper Shafir defended that memory is a cultural and political construction, here is another example: the report that recovers the memory of women in the face of the androcentric tendency to turn personal experience and the particular contribution of men into something that builds stories about different things. In the absence of a report constructed from the experiences of women, the reading of these aggressions – if they were done – would surely fall into the victimization of women, once again in the armed conflict, with the consideration of women as passive subjects, which would inevitably affect the identities of the women of the future. The Memoranda have been able to properly channel that influence that will reach posterity.

Memory work cannot refuse to be a useful instrument to stop the process of victimization of women and cope with the denial of their agency, which allows understanding women as active subjects of voice and agency at the time of readings of the conflict. In this work are the women who have helped write these lines and so many others. Not only are stories being published by women and the imaginary built up so far, but the story that has triumphed and the way to write it are being questioned. An essential step towards the construction of an egalitarian people, since only a memory that integrates the story of the whole community can create a more egalitarian future society.

Fusilamenduak, elektrodoak eta poltsa, hobi komunak, kolpismoa, jazarpena, drogak, Galindo, umiliazioak, gerra zikina, Intxaurrondo, narkotrafikoa, estoldak, hizkuntza inposaketa, Altsasu, inpunitatea… Guardia Zibilaren lorratza iluna da Euskal Herrian, baita Espainiako... [+]

GALeko biktima talde batek eman du kereilaren nondik norakoen berri Bilbon egindako prentsaurrekoan, Egiari Zor fundazioak eta Giza Eskubideen Euskal Herriko Behatokiak lagunduta. GALen aurkako eta, zehazki, José Barrionuevoren aurkako kereila aurkeztuko dute.

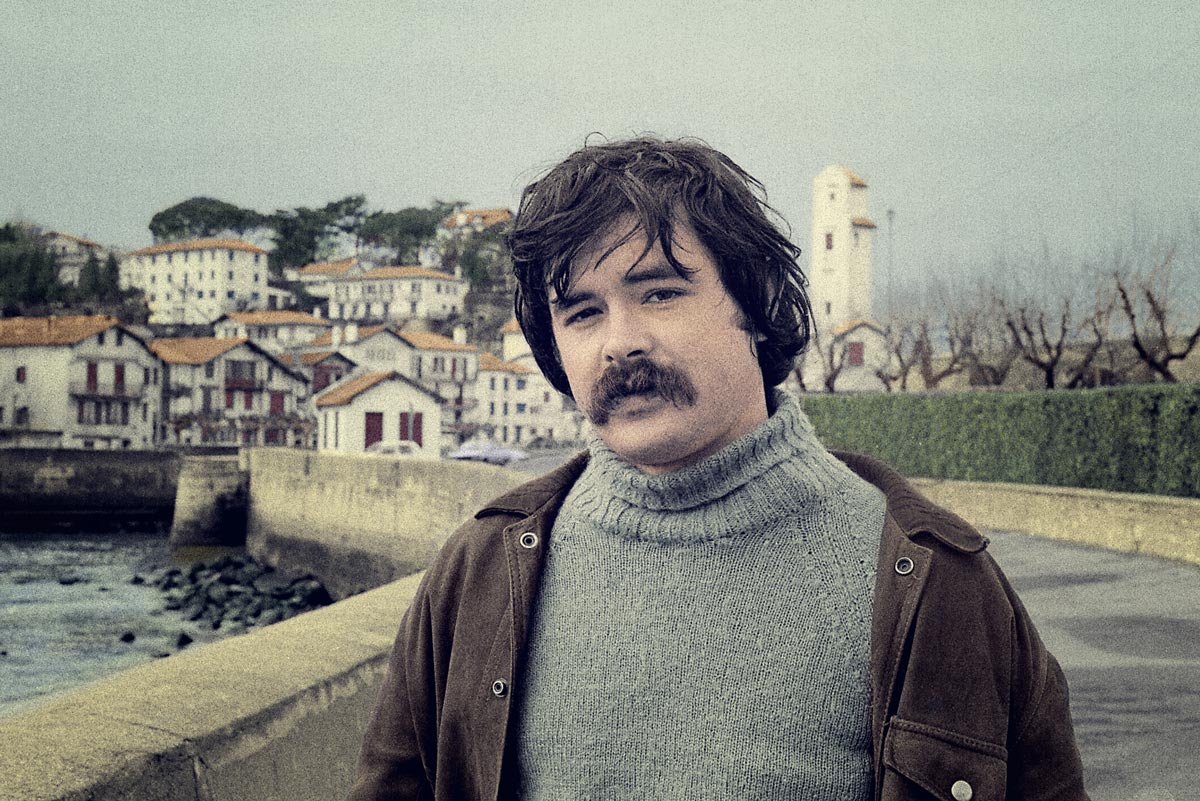

Felipe Gonzálezen garaian Espainiako Barne ministroa zen José Barrionuevoren aurkako kereila aurkeztuko dute, Ipar Euskal Herriko errefuxiatuen aurka abiatu zuen estrategiagatik. ZEN Zona Especial Norte Planaren barruan egindako ekintzen erantzule nagusietako bat... [+]

Maiatzaren 30ean Nafarroako Gobernuak zenbait biktimaren aitortza egin zuen eta senitartekoek Sekretu Ofizialen Legea bertan behera uzteko eskatu zuten. Horien artean, Mikel Zabalza eta Mikel Arregiren familiak. ‘Naparraren’ anaiak ere egina du eskaera hori. Eneko... [+]

Jose Miguel Etxeberria, Naparra, aurkitzeko bigarren saioak porrot egin du Landetako Mont de Marsan herriko inguruetan. Iruñean ostiral honetan egindako agerraldian horren berri eman dute Eneko Etxeberria Naparra-ren anaiak eta Iñaki Egaña Egiari Zor... [+]