'Tretatxu', governor of robbers

- Batxi Landa, Tretatxu, would be no more than another criminal killed in prison if his echo had not persisted in the oral tradition. But, following the trail of short Coplas, journalist Hektor Ortega has produced a biography of an 18th-century rebel who has been arrested. This story shows us that the social bandits were more than what was thought of the Basque Country and that they had the support of the subordinate classes in front of the big ones.

“Ma’am, don’t be afraid, because Tretatxu is a thief,” a voice reassured Francisca Agirre of Bermeo, when at night cox was knocked at the door of his house. A thief that you don't have to fear? This contradictory phrase, which has been hidden among the multitude of documents in a file, carries within itself the essence of social bandits, criminal for justice, hero for the citizen.

The journalist of Deusto Hektor Ortega has recovered from the Archive of the Chancellery of Valladolid this and many other statements by the woman of Bermeo. The book Tretatxu, Governor of Robbers (Txertoa, 2018) uncovers the trajectory of a well-known thief in Bizkaia in the mid-18th century. But in addition to the biography, the author has performed an X-ray of a wide range of societies that identified with her, not for nothing have left us old popular coplas that extol the criminal in the imaginary:

Tretatxu semie

by Larrauri

Landako Governadorie

of the Biscayan thieves

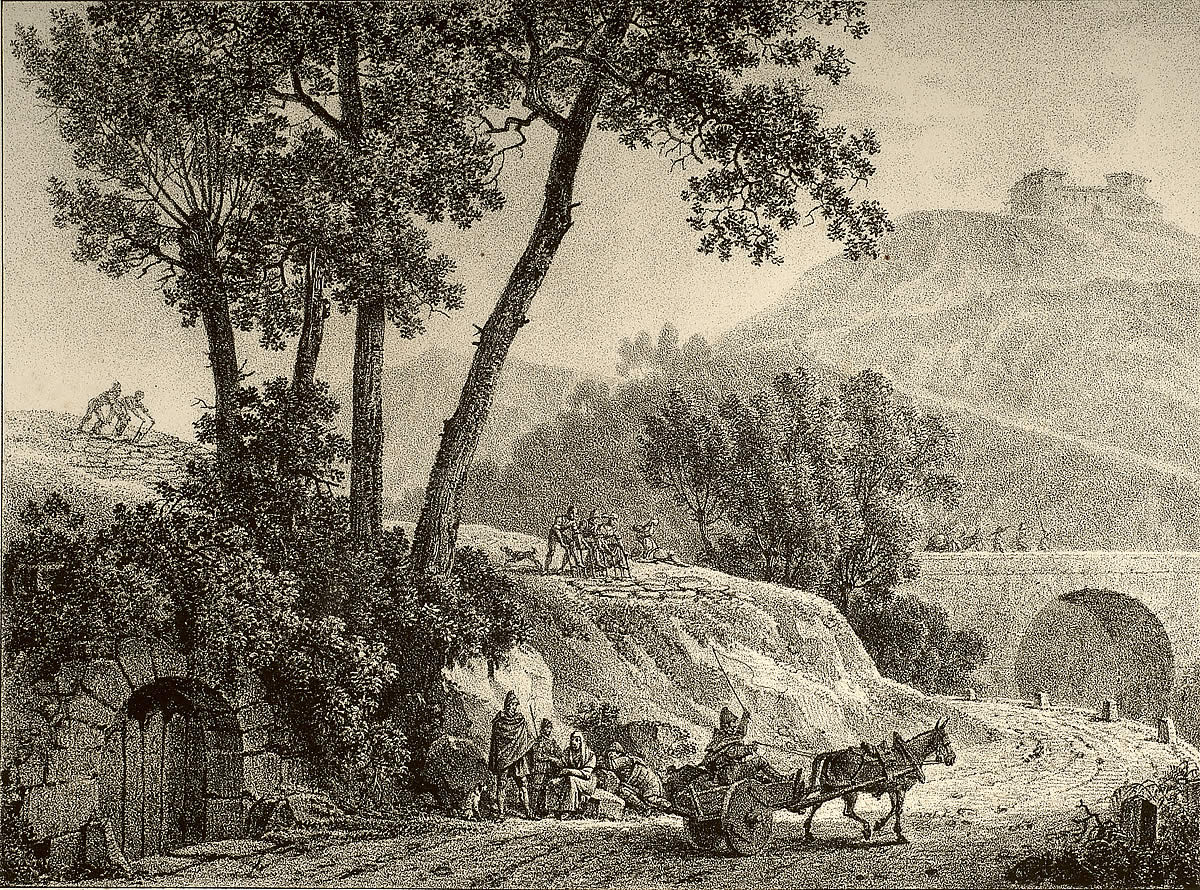

Batxi (Baptist) Landa Tretatxu was born in Larrauri in 1716, in the Landa Solar House, and began his legend on 9 September 1751, when he left Bilbao with three other friends to devote himself to stoning. Short race, which was arrested in 1753 – died eight years later in Valladolid prison, we don’t know how. For almost two years we will see how many robberies, deadly enclosures and leaks occur, especially in the ports between Bizkaia and Álava, going out the way of the arrieros, assaulting the houses of the abades and perhaps also in smuggling, in Baiona, Ataun, Bermeo, Pamplona, Urkiola, Azpeitia... The prosecutor accused him of seven actions, but he implied that he had participated in many more, for which the Bizkaia Corrector sentenced him to death.

A criminal feared in the light of judicial documents or “the excrement of the people” in the mouth of the authorities – as described by the Mayor of Orozko. But separating the fat and broth from here, Ortega has created a very different image of Tretatxu, which has more to do with the social crossbody model proposed in his day by Eric Hobsbawn; the English historian observed that the myth of the generous crossbody that spread around the world had a lot to do with the “prepolitical” protest.

Basque historiography, however, has not so far given such a character to local bandits, except to Manuel Antonio Madariaga Patakon, who embodied the famous phrase “remove the decon and not the deconate”, which also acted “under anti-millionaire instincts”, as suggested by UPV history professor Joseba Agirreazkuenaga. “In Euskal Herria so far we have had the only case in Patako,” explains Ortega, with Tretatxu we have demonstrated a second case, and I am sure there are more cases”.

Why does the journalist say that? In his view, the key lies in reading the sources used to investigate the bandits: you also have to look at the unofficial oral tradition and ask appropriate questions to the official documents. Fortunately, you have found a lot of documentation that had not been analyzed so far about Tretatxu: “It’s a big deal, you have the opportunity to immerse yourself in this person’s life and see what’s behind the words, how people really saw it.”

Hektor Ortega, author of the book: When we go back in history, it often seems that the top guys decided and the bottom guys said "amen." Well, we've already seen that no, if there was a daily resistance, it's clear by reading the coplas on Tretatxu.

In the long pages that make up the judicial criminals, the citizen’s statements require a double decoding: that of the language – we have to know what the translator meant to the words of those Biscayan people who lived in Euskera – and that of the classes, which had a worldwide conception very different from that of the subaltern peasant beggar: “Their concept of justice was not at all the same as what the lords were spreading, they were far away,” says Ortega. The mystified life of Tretatxu thus becomes a battlefield: “It’s very shocking to see that on the sides of the corridors that same thief, the worst of the evil, was the hero that the citizens sang.”

Citizens “did not sell”

A few days after the first robberies of Tretatxu and his friends, on September 13, 1751, writer Manuel Lorra was secretly sent to Mungialde to capture them. Their Chinese were monitored and five other people were brought to Bilbao, but none of them was a crossbody, but the neighbours and relatives who accompanied them. It would not be the only time, since then Tretatxu will flee again and again to the authorities as foxes, you can read in his biography “did not sell it” twice.

Social bandits had the understanding and support of the citizens, such as Tretatxu, and other characteristics that this stereotype gathers: to use violence cautiously and without excesses, to steal away from the community, fame, value… The son of Landa often demonstrated that value. Once, he had the crossing face in the hand of the mayor of Bermeo, who recognized him doing the round down the street: "Batxi, he's standing! ", a woman screamed and the mayor came alive from the isthmus.

This woman was Francisca Barandika Zarra, Bermeo fishmonger and faithful collaborator of Tretatxu. Women will often be seen by the bandits, sometimes collaborating, sometimes covering their actions, always weaving networks: “They are very independent, they do things that were not normal at the time, boldly,” says Ortega. For example, our neighbour of Bermeo had no hesitation in going to Bilbao for weapons and clothing, even though he was in danger, so Zarra was in prison for a while.

The life of Tretatxu, a scene of social conflicts

In Tretatxu's life there is a novel story that will help us understand its nature and its behaviors. Batxi Landa was the owner of the cottage, an honored gentleman linked to the house, “that was a lot in the old Bizkaia law”, but not enough. What happened to him for stoning?

Agriculture was put at the service of capitalism in the 18th century, a few large were enriched and many of the inhabitants were completely indebted due to speculation. The situation impacted in the Uribe area – in Gatika, for example, half of the landlord baserritars became tenants – and also Tretatxu stopped paying interest, even the house caught fire in 1738. According to Ortega, the solution for many was "self-oppression". Or rise up. The route that our thief had taken was obvious.

A 1744 event disrupts the life of Landa, who is caught in bed with a widow. Although she was a woman of the mesocracy of Butrón, of the Tellaetxe family, those great lords will not forgive the humble peasants. They will also not, because they will force him to remarry another person, using the misogynic codes of the Church. Without trial, Tretatxu will be sent to serve in the King's Army for a period of ten years, away from Oran and Cartagena.

This illegitimate punishment will definitively hit Landa's hero, until he is illegalized. After graduating from the Army and repatriating in 1748, Tretatxu and the big ones will continue to face Tretatxu and his colleagues, who will try to persecute him: on their return they will find their wife – the body of the woman used by the power – pregnant, to whom they will appeal in the public square, amid the soka-dantza, on the order of the mayor of Mungia Antonio Tellaetbro. Insult and punishment. Why this hatred? The journalist explains: “It’s an extreme case and it could be a personal case, but when citizenship is set aside, in this case facing the unlegalized, then Tretatxu’s life becomes the scene of social conflict.”

According to Ortega, the case of this crossbody shows that before the subordinate classes had a certain independence, a desire for justice: “When we go back in history many times it seems that the top ones decided and the bottom ones said “amen.” Well, we’ve already seen that no, if there was a daily resistance, it’s clear by reading the Tretatxu coplas.”

Washington, D.C., June 17, 1930. The U.S. Congress passed the Tariff Act. It is also known as the Smoot-Hawley Act because it was promoted by Senator Reed Smoot and Representative Willis Hawley.

The law raised import tax limits for about 900 products by 40% to 60% in order to... [+]

During the renovation of a sports field in the Simmering district of Vienna, a mass grave with 150 bodies was discovered in October 2024. They conclude that they were Roman legionnaires and A.D. They died around 100 years ago. Or rather, they were killed.

The bodies were buried... [+]

My mother always says: “I never understood why World War I happened. It doesn't make any sense to him. He does not understand why the old European powers were involved in such barbarism and does not get into his head how they were persuaded to kill these young men from Europe,... [+]

Until now we have believed that those in charge of copying books during the Middle Ages and before the printing press was opened were men, specifically monks of monasteries.

But a group of researchers from the University of Bergen, Norway, concludes that women also worked as... [+]

Florentzia, 1886. Carlo Collodi Le avventure de Pinocchio eleberri ezagunaren egileak zera idatzi zuen pizzari buruz: “Labean txigortutako ogi orea, gainean eskura dagoen edozer gauzaz egindako saltsa duena”. Pizza hark “zikinkeria konplexu tankera” zuela... [+]

Ereserkiek, kanta-modalitate zehatz, eder eta arriskutsu horiek, komunitate bati zuzentzea izan ohi dute helburu. “Ene aberri eta sasoiko lagunok”, hasten da Sarrionandiaren poema ezaguna. Ereserki bat da, jakina: horra nori zuzentzen zaion tonu solemnean, handitxo... [+]

Linear A is a Minoan script used 4,800-4,500 years ago. Recently, in the famous Knossos Palace in Crete, a special ivory object has been discovered, which was probably used as a ceremonial scepter. The object has two inscriptions; one on the handle is shorter and, like most of... [+]

Londres, 1944. Dorothy izeneko emakume bati argazkiak atera zizkioten Waterloo zubian soldatze lanak egiten ari zela. Dorothyri buruz izena beste daturik ez daukagu, baina duela hamar urte arte hori ere ez genekien. Argazki sorta 2015ean topatu zuen Christine Wall... [+]