"Every single fight is all at stake."

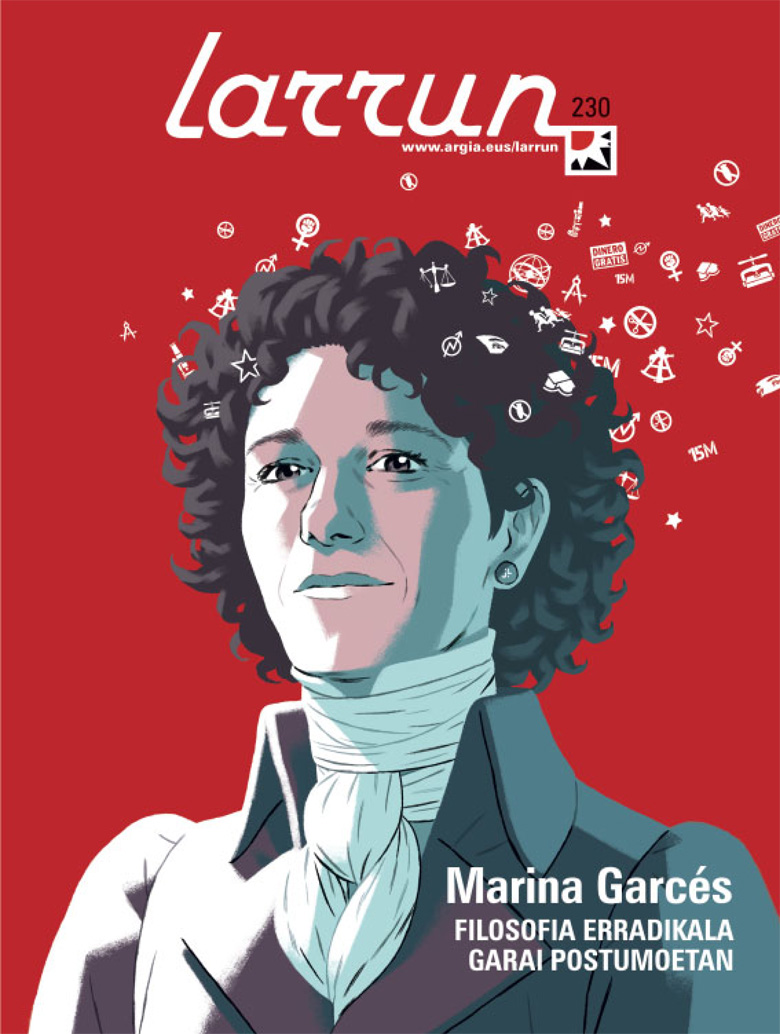

- The astonishing capacity of the Catalan philosopher Marina Garcés (Barcelona, 1973) to make the deep ideas comprehensible and tangible, the clarity of connecting thought with everyday experiences, and an attitude in the convulsive times in which we live: united with those who bet on transformation, more than radical answers, to raise new questions. At the University of Zaragoza he teaches philosophy in recent years and since 2002 he has also promoted the Espai En Blanc project, whose objective is to promote critical thinking and imagine new alliances between philosophy and action.

He has just published two important books, Nova il·lustració radical (Anagram, 2017) and Ciutat Princesa (Galaxy Gutemberg, 2018), because the first makes a rigorous diagnosis of the impotence that many of us feel at this historic moment – “we know everything, but we can’t do anything” – and puts on the table a commitment to deal with this situation: stop believing and thinking otherwise. In Ciutat Princesa, since the occupation of the Princesa film in 1996, he writes a philosophical and vital chronicle of his political experiences during the last two decades. A political autobiography that narrates the transformation of a city and its inhabitants, from the anti-globalization movements to the opposites to the turistification of Barcelona, through the referendum of October 1, 2017, among others. From these two works we have done the interview that you can read below. In his answers he has given us his feet to ask us new questions.

After participating in the conference “The Philosophy Behind the Rojava Revolution”, Marina Garcés has met with us at the cafeteria of the CCCB cultural center in Barcelona. Despite the cloudy morning in the Catalan capital, the Azadi platform, which promotes solidarity with the Kurdish people, has brought thousands of people together. The experience of the Kurds here, at the moment, is of interest, there is no doubt. In his inauguration speech, Garcés assured that there is no revolution without philosophy, no philosophy, no radical transformation. And on Rojava's experience, he stressed that this is not an abstract concept developed on the void, but rather a concrete one that advances in the face of common problems. From this relationship between theory and practice it has much to say, thought and experiences, ideas and experiences will connect throughout the dialogue: the thought that transforms life, the life that transforms thought.

In the book Ciutat Princesa you mention that, from a few words from Michel de Certeau, all the crises bring to light what was somehow latent in society. Given the situation in Catalonia, but also the global refugee crisis, the rise of far-right parties… What is emerging from this crisis that we have been experiencing in recent years?

I would say that they are different faces of the same deep, overlapping crisis: the experience of the limits of civilisation of the economic and political system in which we live. Global capitalism is at a stage where, instead of continuing to spread beyond limits, it has to constantly overcome the borders that it generates. It is clear that the frontiers related to the environment are the most obvious, but the political and institutional limits also appear: classical capitalism was linked to the state nation, it was the one that articulated the world, a world of national and colonial markets. This included a guide dynamic, an extirpation and manufacturing dynamic… A series of dynamics that are not so obvious at the stage of today’s capitalism. And also that idea that at the end of the 20th century and the beginning of the XXI.aren we called globalization, that markets had already globalized the world and that the State was nothing more than a waste that lasted from the previous order, has begun to come into contradiction.

"We can think differently if we live alone in another way, and we will live differently if we only dare to think differently"

In this sense, in Nova il·lustració radical talks about the border and the precipice, as well as the fascination produced by the apocalypse. As you explain, this fascination is due to the inability to imagine a future that does not go through total destruction. It's caught our attention lately, seeing neo-fascist phenomena like Trump or Le Pen, seeing the symbols of critical thinking like Slavoj Zizek are basically good news, because as the system's contradictions get worse, the conditions for transforming it will arise. Is this “the worse, the better” logic a version of apocalyptic paralysis?

Apocalyptic paralysis is really a paralysis of the imagination. The policies that seek emancipation have always been the place to sow the imagination: the political imagination, which is also cultural imagination, the aesthetic imagination, the affective… All that allows you to imagine ways of living otherwise, even leading to a utopian end, to other worlds. This use of the Revelation, both by the factual powers, with their strategy of fear, and by those who announce the death of capitalism, basically expresses the paralysis of the emancipatory political imagination. And that's why my commitment to go and look for the sources of radical illustration that are not the basis of capitalist modernization of the world, but quite the opposite: the possibility of thinking in dissonance with the futures that are written.

He also questions a concrete idea of the intellectual in the last two books: this figure with the mission of showing the truth behind alienation. Is part of your commitment to the field of thought to break the hierarchical relationship between theory and practice?

Yes, and not only as an objective, but also as a condition. One of the most important learnings that has shaped me politically and philosophically has been precisely to live and be in that indissoluble relationship between theory and practice, not only in classrooms and books, but also in my experience in collectives and in social movements. This does not mean that all theories have to go into action or vice versa; it means that we can think differently if we live alone in another way, and that we will live differently if we are willing, if we dare, to think differently in doing so. The thought is to do, the act is to think. That for me is a living learning, not something that has come from some readings, but from many years of political experience, from experimenting with this thinking that transforms life, from this life that transforms thought. That is philosophy to me, understood as a commitment to life, both personal and collective.

"The same arguments you hear anywhere in the press are used to promote the tourism industry: 'Another person has to come to create economic activity, I'm not worth it on my own'

Of course, that completely changes the place of the intellectual. It changes, for political reasons: you place yourself somewhere else in relation to who we are. And, for example, it doesn't let you speak in third person, something I can't tolerate, but it's very widespread among many critical intellectuals who are always talking about "them" or "people." I often participate in debates and think that when someone starts talking about “people” in third person: Who are they? Why not learn to say “we”? That has been one of the main strands of my writings and bets. Learn to say “we”. Not to try to catch the other's identity, but to the contrary: the only way to build a common thought is to work on common problems. They don't have to be the same problem, the same issue, but they do have the attitude to deal with each other together. This places you in a place where intellectual practice and criticism lie within the framework of complicity and alliance. And, therefore, there is no monopoly on knowledge and truth. And that bothers a lot of intellectuals and a lot of others who want to be intellectuals.

It seems to us that in his last book he questions the utilitarian logic that we often use to look at the past, that is, he renounces to value the struggles of the past in terms of “success” or “failure.” Can we rethink social struggles rather than looking at what they got, the possibilities that they opened up?

When I started working on the basis of these writings that have ended up being Princess Ciutat, the question was: What do you want to count? That is, the need to count is one thing, because we have a human need to tell what you have experienced. But what do you mean by what you have lived through? I was not interested in taking stock of successes and failures, of successes and failures. But then, what does what counts? I understood that this was a serious matter, which was to follow the footprints of the effects of the transformation of what we have experienced, rather than what we have gained and what we have lost. What has changed our experience? This is a question that appears at the beginning: what has happened to us, in that profound sense; what we have transformed ourselves and what we continue to transform.

"The experience of the world is becoming impossible. We consume facts, information, knowledge… but they do not create experience and it is the experience that transforms you"

I believe that all this has more to do with studies than with conquests. There is a whole revolutionary and emancipatory epic that is still based on the language of conquest. And social conquests are fine, but the other side of conquests are failures. What I wanted to tell you, because I think a lot more about this politically, is that the subjective transformations that come from struggles, from experiences, from studies… from their experiences. I think if there's something that doesn't turn back on the things that you've experienced, it's there, not on the objective facts. We are lately trapped in ideas such as the “counter-revolution”, the “counter-reform of reform”, or now, from the M15, we open moments of rebellion and suffer the subsequent involution. These dynamics are changing more and more rapidly. Meanwhile, inside, you're moving the edges, the limits, the ways of seeing the world, and that's changing. I believe that the observation of these transformations gives us the keys to making political readings very different from our present day.

This coincides with some passages of the radical Nova il·lustració, which looks to the past, to the great project of the Enlightenment, but without falling into the logic that indicates the failures that the project had. Instead, he seems to have tried to sharpen the tools that the Enlightenment brought. What value does it have to look at the past like this? How can we once again grasp concepts such as critical emancipation, once exacerbated?

You tied my last two books as if they were an exercise for the past, and it's true that there are, but I don't know if I would say so. Perhaps because it was a real intention, not to look at the past, but to look at what the previous book called “unfinished philosophy”, something that seems very similar to the style of Walter Benjamin or Gilles Deleuze. An idea that tells us that our present is full of what has not happened, of what has not taken place in the construction of this world. Or, to be more accurate, as I say at the end of Ciutat Princesa, which is made up of everything that has not agreed that things are like this.

"There's a political job to do. Learning to pursue situations of oppression, which today are much more vague than before. If we can detect these situations, we have more ability to say 'no'.

Everything that is not put in a place, what is not up to date, what has not happened, what has no place, I do not understand it as a failure, are threads, and over time we can go looking for them, both in the past and in the present. And that gives us future memories, those I mention at the end of Ciutat Princesa. Recovering the final image of the radical Nova il·lustració, these “injunctions” are. And I think I do this in my latest work: weave time to work experience, because I think one of the wars of our time is against experience. This was also said by Benjamin, and it's a contemporary condition: making experiences about the world is becoming impossible. We consume facts, information, knowledge… but they do not create experience and it is the experience that transforms you, and in addition, it can be transmitted and retrieved. The information tells us: “This has happened.” And yes, what do you understand, but how do you make the experience from there? I think the condition is that time is sewn, that does give us very strict tools. In the Spanish edition of the book I didn’t know very well how to put that “sharpening” in Spanish, mixed “sharpening” and “fine-tuning” and I don’t know which one I put at the end. I joined the figure of the uncompromising weavers and put that we needed “sharp tools,” as I had a needle in my head. But they were also “tuned,” because they had to be very thin. Also tuned in the musical sense, because you have to invent them with the record of what you mean. And I think that's basically the task of critical thinking, not so much to judge reality or to bring it to judgment, but to do a very fine job of discrimination, to discriminate, to adjust things that are not tight, and that's what these tools have to work on.

As he mentions “the unfinished”, he says that the M15 movement was a turning point, because the references that brought him to the collective imaginary have perhaps been diverted, but have not been exhausted. What is about to exhaust from the M15? Where can we look for the living footprints left by this phenomenon?

I believe that in one of his most well-known expressions: “They don’t represent us.” Perhaps we are at a stage where this “do not represent us” has been inverted: as they do not represent us, we vote for the strongest; and that may also be one of the faces of the phrase “do not represent us”. But I don't think anyone feels represented by a party that they accuse of being a criminal group, that is, the PP. This whole mechanism which served to legitimize some political institutions and some economic policies has been broken. But being broken doesn't mean that something good is going to come out of it. The M15 declared this break, the end of the consensus. The logic of the “least harm” of the Spanish Transition no longer serves any purpose.

"One of the main bets of my writings is to learn to say 'we', because the only way to build a common thought is to work common problems"

This opened a hole, a crack that was expressed in very different ways. He also pointed out one direction, and I think there are some small traces, for example, that saying “they don’t represent us” doesn’t mean that what is public is not ours. I think this is something that has been forgotten about the M15, and it was very important. It worked with the M15 and the Tides and, indeed, it could be said that in the face of the crisis and corruption – one of the great achievements of the M15 was that the crisis and corruption entered the same yoke – that the health is ours, that the school is ours, that “this will not touch”… Because it is ours, not yours. On this plane, I believe that the delegitimization of power still holds him, but turned into his instrumentalization. On the other hand, the regeneration of the public, understood as “the public but not the state”, has been greatly reduced, although it remains alive in some strata, such as that of the social economy or, very clearly in Catalonia, that of the defense of the public school. But I think the north is lost, because there is an extreme disproportion between the erosion that supports the public and the common and the concrete possibilities of defending it. But there it is, and for me it's key. At the end of Ciutat Princesa, I turn to that, to how to make public what's public, which surely means to disstate, but not marginalize.

In the book he mentions a slogan from the late 1990s: “Consensus is censorship when everything can be said.” Now, however, it seems that we are returning to a harsh sense of censorship, in which we are told that everything can no longer be said. Is this a sign of the strength of the system or, precisely, of its weakness?

I believe that our generation has difficulty in putting ourselves at this present moment – things are happening that are in days, hours, minutes – and in part it can be because we are emerging, like Jacques Rancière, from that consensus-based democracy. This idea said that there is no more power than that which is able to create and impose consensus, especially because it has the capacity to impose a thought: that only what is agreed is democratic, thus expelling all discrepancies from the democratic sphere.

"It is more important for me to follow the traces of the transformation effects of what we have gained and what we have lost. What has changed our experience? If there's something that doesn't turn back, there it is."

In the current situation, power is being reinforced with actions of direct repression and, therefore, also classical censorship; and for me, at least from the last experience of what is happening here, the most terrible thing of censorship: self-care. Without having lived through the forms of classical censorship, it was something I didn't think about: that when there is censorship, the greatest censorship is self-care. And we're already living that, it's happening. So is power weaker or stronger? It is clear that it is more violent when it comes to fulfilling its duties. And I don’t like to fall into easy readings, saying that “the more violent power is, the closer death is.” We say it many times, perhaps to reassure ourselves: “Trump is the agony of the United States,” “agonic capitalism is extremist capitalism,” “state power hardens when it loses legitimacy”… Yes, I think all that is true, but not only that. I think it's a rather complacent diagnosis, as if we're looking at the agony while we're being killed. I have doubts, I don't know. It may act hard because it's strong. And power is strong. This democracy of consensus may have accustomed us to an almost administrative situation, to totally depoliticizing logics. And when politics returns, so does the struggle of sovereignty, because after all that is: Who decides what? This is the fundamental question of politics.

Certain traditions on the left have criticized the M15 or the Zapatistas for wanting to transform society without taking power. Do we have to rethink the issue of power takeover, seeing the fascination that wakes up among those who want to change things?

In my experience of politicization, of the time and of the generation, that fascination of power hardly existed. The parliamentary left was entirely in the hands of the system and, therefore, the question was not whether it was fascinated with power, but that it was part of power, even as an opposition. And the movements that made a more radical critique, the ones that proposed a more transformative politicization, we didn't look to power, a territory that was completely out of our interests. A part of the surprise that has led me to write Ciutat Princesa has been that the step has been taken to create what in the Spanish state has been called “new politics”, which we have also seen in other places, such as Mexico: To say “we must return to the institutions”. On the one hand, because they're stealing everything. But on the other hand, because we've been doing revolutions for 20 years that don't change anything. There is a double diagnosis: on the one hand, the urgency – social, by the crisis, by corruption… – and on the other, a kind of tiredness, the impotence, to be in a constant mobilization that only indicates what is not changing.

"Critical thinking, in my opinion, is not so much judging reality, but doing a very fine job of discrimination, discriminating, adjusting things that are not tight."

I try not to fall into dichotomy. Not purism – “you do not have to touch power”, understanding power as acting in some institutional functions – but it does not fall out of the donkey either, as if the movements had suddenly reached political maturity, as if in the end they had become “responsible”, because “occupying places and in the jungle of Lacandona we do nothing”. I try to think, like those lines that I've taken Gabriel Ferrater, "dare to be able." That idea: What is it really to dare to do? to dare to do things without seeking refuge in the self-indulgence of the minority, but without justifying power, without thinking that only the one who has power can change things, which is something I will never believe, because the one who has power normally does not change things, stabilizes and monopolizes. I look for that place that can empty the power of a power. And I think there are ways to do that. For example, this meeting today on democratic confederalism. This way of de-statalizing power, creating institutions capable of self-organizing their statehood, their accumulation of powers… And on that there are many experiments: from the holding of political parties that do not professionalize politics, which will be platforms of delegation of collective tasks and not tools of concentration of representation and power. The human imagination is capable of thinking many things and in that direction a lot has been thought about. And I think the road is in the search for that line.

It has also drawn our attention to the importance it attaches to the places of political action. In Ciutat Princesa you have questioned the centrality of the neighborhood as a place where to carry out transformative political actions. He mentions, for example, the problems that the M15 had when he tried to spread from the plazas to the neighborhoods. Is it important to rethink the relationships between territory and political action?

It is an important issue, given that political geography is undergoing a very rapid and violent transformation. Real estate violence, migrations, precariousness of work, we no longer think that we live in the same house more than a rental contract... So many things are happening, which is no longer just a global phenomenon being analyzed in recent years, but a concrete vital experience: the relations of proximity and distance have changed. On the one hand there is the old premise, that of radical democracy, direct democracy or basic politicization, which postulates that the place of autonomy is in proximity, the space of encounter in the face of political experience, and on the other hand, the question we should ask ourselves: Where is the closeness today? I still believe that there are relations of closeness, which are key to building a radical democracy, but perhaps that closeness is no longer in what the imaginaries of the previous politicizations gave as close.

"When politics has returned, so too has the sovereign struggle: Who decides what? This is the fundamental question of politics."

The neighborhood, as an element, has a whole tradition of struggle, of neighborhood movement, a collective identity. I see that today, in a city like Barcelona, it is being taken as a new map of political work: the city is the neighborhoods of the city. And so, from José Luis Oyón, a very interesting anarchist urbanist, I return to the idea of “neighborhood”, which is not exactly the same. The neighborhood, if objective, I don't know where it is today: that there are basic services, for example, a library or a health center, is something else. The neighborhood as a unit, as a common place to live for each of us, is sewn with many other spaces and times. How could we analyze our neighbourly relations today, taking into account the exchanges of our usual vital elements, but in our current lifestyles? The maps that would surely leave us would be very different from those that would be published in a Barcelona in the 1930s, for example. I think there is an interesting solution to break with another dichotomy, the dichotomy of “global or local”; “neighborhood or globalization”; “patio of my house and neighbors or global networks”… When distance is not contradictory to proximity, we can learn to draw political maps that will not turn us into some sort of abstract citizens of the global world, nor some new indigenous people living in fundamentally false neighborhoods.

In this last book he says: “Living on the sidelines only temporarily alleviates the usual obstacles to coexistence.” We have understood this phrase as a criticism of the construction of community experiences away from life on the streets and outside the cities. 219. In the interview we gave to Kristin Ross at LARRUN, he put this debate on the table, but emphasising that people like the ZAD in Brittany have been able to make progress thanks to the existence of non-urban phenomena. What can we learn from this tension between the city and the rural environment? What possibilities does each space offer for transformation?

In Espai en Blanc we have always used a phrase that says: “We want to grow on the margins without being marginal,” and I think it answers the question. I am convinced that, as far as experiences like the ZAD are concerned, there are times for decentralization, to go in the form of an angle, where you can go to a place where there are no hotbeds of news, speculation and many violence that cross our world. And that there is a power, the power of the escape line, those other worlds, those other forms of struggle and those other relationships that allow us to come in and out of the heart of the beast.

"There are closeness relationships that are key to building a radical democracy, but maybe that closeness is no longer the same as we already knew."

What I wanted to see with this phrase was an idea, not a very new one, that there is no real exterior. One thing is, you put yourself on the edge so you can do and fight for a habitable life, and another thing is the possibility of actually going out, and not just ideas based on radical self-sufficiency. We take her with us. In this life balance in Ciutat Princesa – which have gone, which has not, what has happened to those who have gone, what have found in those other ways of life… –, there are softeners, but there is no salvation. And I think it's good to know that it's not to fall into the fascination of the apocalypse, but quite the opposite, to know that there are different experiences of oppression, but that no one is saved. And if no one is saved, the corresponding forms of survival, forms of struggle and relationships must be built from each place.

In relation to this, where we go, where we go, he defends in Nova il·lustració radicació the critical power of knowing to say “no”. But maybe things were easier, let's say, in the 1970s? The worker who worked in the assembly chain knew, at least, who he had to say no and where he had to go. But if we are our bosses, if our factory is our own life… To whom shall we say no and where are we going?

Perhaps we are obliged to have a perception of the relationships of domination, exploitation, alienation and disdignity, much more linked to the situation. It is not so much a question of saying “no” to the patron, but of “no” to this situation. And we're constantly going through humiliations and outrageous situations, whether or not they're more obvious. There is outstanding political work, also aesthetic, perceptive, sensory, and that is learning to detect those situations, which are much vague. And as we acquire the capacity to perceive the situation, we achieve a greater subjective capacity to say no “yes” or “no”, but to what extent. Everything “how far”. In the precarious lives, in which they are in permanent transformation, in which nothing has clear interiors and exteriors, those “no” become “to what extent”: “I have come here, I will not renew the contract”.

It offers a strong vision of the tourism industry: rethinking tourism as a extremism. We're used to talking about extractivism in other words, like the plundering of natural resources, which is normally colonial relations in and behind the countries of the Global South. Can we say that we are living in our cities some forms of exploitation that have previously been applied in those countries?

In one of the talks this morning you said that: don't forget that colonialism is always auto-colonialism and that auto-colonialism has never ended. One of the lessons I've given in these years in college has been the Comparative Philosophy of East and West, and I've always said this: colonialism never happens just from the West to the world. For the West to exist, it needs a process of colonization of itself and, therefore, we cannot decolonize the world without decolonizing ourselves from this West, which as a center we have built, in whose peripheries other things happen; but those other things have also happened here.

"In order to exist the West needs a process of colonization of itself and, therefore, we cannot decolonize the world without decolonizing ourselves"

I think it is important to take the usual extremism and take this leap by applying it to the mass tourism industry, because so the logics of exploitation are followed up. There's an image, a kind of mirror that has built the center-periphery relationship, and it says that from here we make you look at what's going on in other places, as if it's something different. This often makes us very incapable of seeing the logics of exploitation that occur in our own territory, which, in reality, are the same logics under other aspects and with other levels, perhaps not in intensity, but in their consequences. For me, to see in evidence that the tourism industry is an extractive industry, it is enough to apply the parameters that define extremism, and I do so in this chapter of Ciutat Princesa. It is part of a talk that I made at the CCCB and that caused a total scandal: there were the majority of the leaders of the previous city council, the tourism consortia, the companies that manage the brand Barcelona… We were all and, of course, this round in the mirror, saying “now let’s look around”, gives a very different result from us. And it breaks it, and that was my goal, with the arguments of the colonized that we use to justify tourism: “If not, what are we going to do to live?”, “tourism brings investments”… These are the same arguments that you hear in any place that has put you in a situation of oppression, that is, “another has to come to create economic activity, I myself am not worth it.” The arguments to justify tourism are always of this kind, let us listen carefully and see if we accept that game. But if we admit that, let's not think that this is more beautiful than a soy field or any other grass in Central America.

It seemed to us that this reading of tourism has to do with a process of reorganisation that is suffering the division of labour at international level. To deal with it, it would seem that we have only been able to develop very local repertoires of struggle, but it also said this morning that “every concrete struggle is a challenge of everything.”

It's related to a way of doing philosophy. More than abstract theories that contain everything, what we need is to see what implications are there in every thing, in every struggle, in every book, in every case, in every question, towards the totality. It is a reverse reading: from the whole to the part it has been a way to develop revolutionary and modern thinking. The opposite is that, starting from the concrete, do not remain in the particular, which has also been one of the derivations of postmodernities, of some ways of understanding the concept of difference, or the idea of the fragment… One of the diseases that current critical thinking has is the poor fragmentation, which is condemned to particularism, to micro issues, and that is not a well-understood micropolitics. For me, a well-understood micropolitics is that in the concrete struggle everything is at stake: in every life that goes crazy, in every life that says that “so can’t live”, in every rental we recognize; even in every war, in the city of Kobane, which seems to be in the limbos of time… in all of them are woven all the struggles.

If we put ourselves there, the impotence of our time can start to spin and also the concept of power that we mentioned before. Because the sum of each part will not produce the change of everything as a result, the parts will not be added, but each one is our world. I can't cover the whole world, none of us can experience the whole world. But in every dimension of our lives is integrated a way of imposing the limits of the world. I think we have to learn how to touch them and open them from the lives of each of us, where we actually got to touch them.

Haurtzaroaren amaiera eleberri distopikoa idatzi zuen Arthur Clarkek, 1953. urtean: jolasteari utzi dion gizarte baten deskribapena. Eta ez al da bereziki haurtzaroa jolasteko garaia? Jolasteko, harritzeko, ikusmiratzeko eta galdera biziak egiteko unea. Ulertzeko tartea zabalik... [+]

Une delikatua igarotzen ari den zure lagun minak Taylor Swiften kontzertura joatea proposatu dizu, baina kide zaren elkarte ekologistak elkarretaratzea deitu du, abeslariak sortuko duen kutsadura salatzeko; nora joango zara? Dilema etiko horri erantzun diote gazteek, baita... [+]

Epistemology, or theory of knowledge, is one of the main areas of philosophy, and throughout history there have been important debates about the limits and bases of our knowledge. Within this we find two powerful corridors that propose different ways of accessing knowledge: The... [+]

Entrepreneurship is fashionable. The concept has gained strength and has spread far beyond economic vocabulary. Just do it: do it no more. But let us not forget: the slogan comes from the propaganda world. Is the disguise of the word being active buyers? Today's entrepreneurs are... [+]

Isn't it a sign of pride to look at the people in front of me as if they weren't people? Yes, of course yes. But how can we expect others to understand? Understand, observe, look. Does wanting to understand others not require this proud attitude? Knowing what it is to be a person,... [+]

Are we running out of shame? This is the diagnosis of several authors today. Is there no longer a look that can embarrass us? Another thing that Jean-Paul Sartre described in 1943 around shame is that on the other side of the lock, with the eye stuck in the key slot, a person is... [+]

Predicting the end of anything has become fashionable. The end of the human being, ideologies, community, authority, philosophy, or democracy. Are they labels full of sensationalism?

Maybe it was Francis Fukuyama who started that final fashion. After the collapse of the Berlin... [+]

The most promising futures are more concerned about the future than the long-term ones. It's the CCCLXIX law of life. It seems like a mouthpiece, but the laws of life I don't write them, but life itself.

That law, like all authentic laws, has exceptions, but what exceptions are,... [+]

Today there are many apps to buy friends: The best known are AlquiFriend and Ameego, which seem to work very well, especially in the big cities of the United States. They have about 600,000 users. Pay 120 dollars to someone and for a couple of hours you go to the restaurant... [+]