Women have the key to quenching the thirst of the Sahara

- It is known that water is essential for the life of living beings and human beings. The United Nations has integrated into its bases the right of all human beings to water. But how does that right live, for example, those living in the Hamada desert? The difficulties in obtaining quality water in the Sahrawi refugee camps have made it a challenge to ensure that all citizens have access to water. The Association of Friends and Friends of the RASD of Álava is working for this.

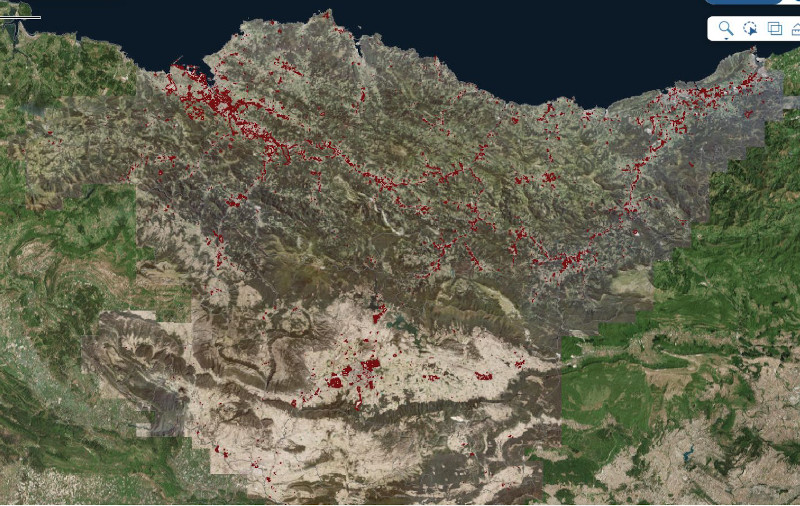

Elma: In Hasaní, in the Sahrawi language, water. Elmaa is a word of particular relevance in the refugee camps in Tindouf, Algeria. In the dry area, where the temperature is 45 degrees during the summer, it is no less. Some 165,000 Sahrawis have been living in the camps created in the Hamada desert for over 40 years, waiting to return to their country. The Sahrawi struggle is a symbol of resistance and the daily life of refugees in the camps becomes a form of resistance.

In 1975, Morocco occupied the Western Sahara, until then a colony of Spain, through the invasion known as the Green March. As the war broke out, thousands of citizens were forced to flee their homes for a time that was supposedly very short. “As they fled the war, the Sahrawi refugees headed to where there was water to set up camps,” explains Geert Demon, a member of the Association of Friends of the DARS of Álava (Democratic Saharawi Arab Republic).

In fact, there are large bags of water beneath the land of the Tindouf refugee camps. In the early years, refugees were extracting water from family wells from probisional wells by themselves by hand. However, in 1994, torrential rains caused flooding and the lack of an adequate sanitation system caused water pollution and a cholera epidemic in El Aaiún. The Sahrawi authorities closed the family wells and began organizing water management.

Fossil water under the desert

It is a complex water supply system that is currently being used. They extract the water from wells that are about a hundred meters deep outside the urban centers. “Fossil water is the one under the camps, which has been accumulating for thousands of years. Fossil water means that the amount that comes out will never return, it's like oil." However, Demon has immediately underlined that under the winter camps there is a quantity of water for thousands of years.

However, the water quality they obtain from the drilling is not entirely good: “Contains large amounts of salt and nitrates.” That is why osmosis plants have been built for water treatment and a chlorination system has been introduced. “However, these facilities do not have sufficient capacity to provide treated water to all the inhabitants of the camps. Therefore, they alternate in several willayas (camps): for a time the treated water, not treated in another section,” explains the colleague. In Dajla's willay, for example, they only take untreated water, because they don't have osmosis plant.

Once the water is extracted and treated in plants in some cases, how is the distribution performed? They have two forms: in some camps through tankers and in others with piping networks. The trucks collect the water at the outside points of the camps and dispose it in the tanks that stack the families along the road, led by a representative from each neighborhood, always a woman. The water distribution network by pipelines does not reach each house either: there are community sources, and it is the representative of each neighborhood who is in charge of incorporating the flexible tube into the source and filling the deposits of the families. “After 40 years they are very well organized and very accustomed to distribution,” says Geert.

The Saharawi woman, responsible for water distribution

Although the right to water belongs to all, women in the Sahrawi camps are responsible for that right. “Every woman with family obligations is entitled to a cubic meter of water. It doesn’t matter if the woman is married, separated, or divorced,” says Geert. However, after this official division, a certain redistribution of water is carried out through solidarity between families and neighbors, depending on the needs of each family.

Women are also protagonists in the organization of water distribution. Each of the dairs, urban centres spread within the willay, has its own Water Committee, all of them female, composed of representatives of the four districts of each of them, the President and the Secretary. The presence of women in the regional direction of water and, at the national level, in the Ministry of Water and the Environment is lower, as as the chain increases, men are being imposed.

.jpg)

Asked about this important role of the women’s committees, Algerian activists have told us that it not only stands out on the issue of water, but on the whole of society’s organization: “There are also other committees, such as food or certain services, in which women also predominate. They have control of what is distributed in the camps and they are in charge of reaching out to everyone,” explains Usune Zuazo, a member of the association. In fact, it was the women who built the camps and organized local society, and although after the war there was a new division of roles and functions, they have all stressed that the Sahrawi woman has played a very important role in local society.

Association of Friends of the RASD of Álava and water project

“Our task is, among other things, to support the work of the SEAD Government and to defend the right of self-determination of the Saharawi people.” These are the words of Raquel Calvo, a member of the association. In its 30 years of experience, many projects have been launched with this perspective, including water.

The members of the association observed that the water distribution, despite its problems, was more or less correct, but failed at the last point in the chain: “The families’ cubic meter deposits had great problems: they were zinc galvanized and were very obsolete, oxidized,” Geert explains. The rust had drilled many deposits, so the water was lost and the water quality deteriorated. A deposit substitution project was submitted to the Basque Government in 2015 and a subsidy was requested: with the aid received, the RDA Government was able to purchase almost 3,000 new polyethylene deposits and brackets for its height.

In this first project it was possible to modify half of the deposits to be replaced as a matter of urgency, and in 2017 the Basque Government approved the second part of the project, in which a further 1,700 deposits and supports are to be replaced this year. In addition, a tanker truck and parts for repair will also be sent to the camps within the project.

Saharaz Blai bideo lehiaketa antolatu berri du Arabako SEADen Lagunen Elkarteak. Euskal Herriko eta Saharako errefuxiatu kanpamentuetako gazteak uraren gaineko hausnarketa egitera bultzatzea izan du helburu lehiaketak: “Zein harreman dugu urarekin? Ba al dakigu nola eta zein baldintzatan iristen den gure etxeetara? Nork kudeatzen du? Zer gertatzen da isuri kutsatzaileekin?”. Galdera horiek planteatu zizkieten parte-hartzaileei elkartekoek.

Daniel Bengoechea de la Cruz eta Oihane Alonso Escudero lehiaketako irabazleek Tindufeko errefuxiatuen kanpamentuetan ura kudeatzen duten emakumeen inguruan dokumental labur bat grabatzeko aukera izanen dute orain. Elena Molina dokumentalistaren gidaritzapean eta EFA Abidin Kaid Saleh kanpamentuetako zinema eskolako ikasleekin batera eginen dute lan gazteek esperientzia aberats horretan.