The cry of the forgotten in demand for truth and justice

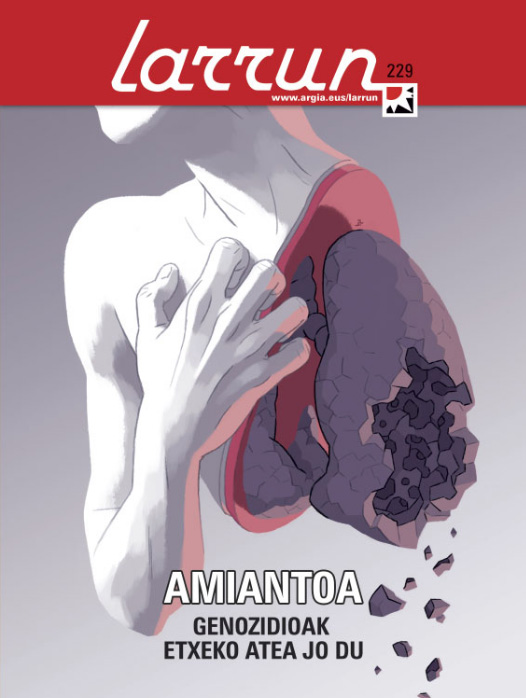

- We can close our eyes and say that the alarming amounts of cancer are the toll to pay for today's life. But the truth will continue to penetrate into the bones of buried corpses: every disease has a origin and a responsible one. Asbestos will kill millions of people in the coming years, probably the first genocide in history to be known beforehand. It could be avoided but it was not done. The fibrocement lobby intentionally concealed its risk and from the 1960s to the 21st century it has been massively eaten and breathed by both workers and the environment. 40 years later, we call death. Thanks to the work of victim associations, public institutions are becoming increasingly difficult to get through – they have recently agreed in the Spanish Congress to set up a Compensation Fund. But those affected by asbestos still have to make a long crossing through trials or gain recognition from the administration, which happens in many cases after their death. Despite the fact that in Euskal Herria and in most places in the West asbestos is banned – what is different is the damage that will result from thousands of tonnes accumulated in buildings, schools and corners – in countries with more than 70% of the world’s population a lot of lethal mineral is being produced and manipulated. At the end of this LARRUN brings us a fragment of Maria Roselli's book The Asbestos lie (Asbestoaren gezurra): “Unfortunately, it’s not a historical curiosity,” says the journalist.

The newspapers have scarcely let the teletype go. The woman worked for 22 years in an Errenteria Insulator Factory, worked with car battery covers, but they were not empty plastics, but dangerous artifacts made from asbestos fibers, and he sank each day one quilt after another, took off the tips with his hand or blowing. Three decades after leaving their job, asbestosis occurs and now, the multinational that bought it must pay 30% of the benefit for occupational disease through a judgment of the High Court of Justice of the Basque Country. But the sentence is not firm and it is very likely that the woman will have to go back to court about to burst her lungs, as she has done over the past five years.

This kind of news comes to us frequently, even more serious. As we write these lines, a short message has been put on the timeline of Twitter: the sixth person died from asbestos this year, the artajone working woman of the foundry of Tafalla Victorio Luzuriaga, today belonging to the cooperative Fagor Ederlan, who had not yet recognized her occupational disease. When the reader receives the journal, the list will be longer, as Euskal Herria is getting wet with this epidemic. Only in the four territories of Hegoalde since 1993 has official statistics indicate that at least 1,494 people have lost their lives.

Mesothelioma or pleura cancer is directly related to the use of this mineral, also produces asbestosis and lung cancer, and recent studies indicate that cases of laryngeal, esophageal, and even ovarian cancer may be related to asbestos. Being so dangerous, why has it been used?

Asbestos can be found in over 3,000 products, in some cases directly and in most cases mixed with cement. It is believed that it can be in a home in 25 places: kitchen, tubes, scissor, heating system, thermos and abrasive toothpaste. Although it is already banned, it is still there, it is not a problem yesterday.

It can be said that the reverse story of the memory is that of the victims of asbestos: the first forgetfulness and finally the drama. In short, as the expert Paco Puche says in his last book, these have also remained in the “corners of the margins of the history of asbestos”.

Its curse is a striking feature for resistance: getting rid of chemically or with heat is very difficult and has great flexibility. Asbestos, in the Greek sense, means “inextinguishable”, and the other word, asbestos, is “incombustible” in the original Latin used to refer to this mineral. The tiny horizontal crystallized fibers aren't seen, they don't smell, they don't feel, they're so small that they're suspended in the air or trapped by water, which facilitates access to the body. Over time, moreover, it is broken – it is not blurred – and it spreads further.

As an insulator it is a totally efficient material, that is why it went through the automotive – in all its forms of transport – the buildings and industries and workshops of the Basque Country in the 1970s, 80s and 90s. Of these powders, the deaths of today, because the disease occurs at thirty or forty years old.

“Asbestos is synonymous with death,” Juanjo Basterra has told us, it is also a synonymous silence, a business at the expense of the lives of others, the intrusion of those who have the power... but above all it is a struggle.” The journalist who has researched the subject in Euskal Herria has given voice to the victims of asbestos in the book Cuatro Lunas (Pepe Rei Kultur Elkartea, 2016): “Those who for years are tearing and undoing inside, although fear and suffering have knocked them on the door, have given their faces.” It can be said that the reverse story of the memory is that of the victims of asbestos: the first forgetfulness and finally the drama. In short, as the expert Paco Puche says in his last book, these have also remained in the “corners of the margins of the history of asbestos”.

War Booty, Slavery and Capitalism

Puchek Asbestos. In his publication A hidden and unpunished epidemic (Catarata, 2017) has summarized all his knowledge – one of the basic sources of this report – and among other things has linked the oppressive origin of the asbestos industry with capitalism. In 1920, the Swiss family Schmidheiny bought a company with a fibrocement patent and baptized it with the name of Eternit – remembering the eternal nature of asbestos. That's where it all started.

The asbestos industry spread to many countries and together with other families linked to the company Eternit created a large oligopoly around this business. With the largest asbestos companies in the world, they held the SAIAC poster, including the British Turner & Newall, the American Johns Manville and the Spanish Roviralta, which would later be handed over to the March family under the name of Uralita. The concentration of capital was huge, as at times these companies benefited from 20% of the yields.

But all this money was based on the oppression of workers, on relations with dictatorships and totalitarian states. In 1992, Stephan Schmidheiny closed his factories and mines in South Africa. Why? This is what Maria Roselli, a journalist, asked a South African trade unionist: “For with the end of apartheid he could no longer exploit the blacks.” They have long learned that slavery can be one of the substrates of modern capitalism, both Catalan and Basque businessmen, in the plantations of Cuban spiders.

A similar situation was taken advantage of by the banker Juan March Ordinas in the post-war autarchic Spain. After financing the 1936 coup, it acquired the monopoly of the importation of asbestos and in 1943 it was made with the large Cerdanyola fibro-cement factory to produce the well-known Uralita, manufactured with the asbestos of the Russian Urals. Franco declared asbestos as a “mineral of interest for national defense” and started a white gold mining business in the Sierra de Ronda, Andalusia. Hundreds of poor peasants from villages like Mijas, Ojén and the like were “hired” to land, transporting dust carcinogens with donkey without any kind of protection.

And in the Basque Country what? There were no big businesses in the production of asbestos, but Basterra said it was very present in many places: “It should be noted that in the Spanish State some 800 companies were imported and in Hego Euskal Herria they were about 85. We're a black spot. Asbestos was mainly used in furnaces, shipbuilding and train and car brakes, the most important sectors here.” In a study carried out by the Spanish Foundation for the Prevention of Occupational Risks in 2002 we can observe that all relevant firms in the Basque industry imported asbestos: Patricio Echeverría, Altos Hornos de Vizcaya, CAF, Trash Española, Michelín, Laminaciones Lesaca… All had to do with the Franco regime, some even participated in the uprising and in the so-called “war booty”.

By that time many epidemiological studies had been carried out to alert them to the risks of asbestos. Lucy Deane Streatfield gave the first serious warning in 1898. She was one of the first women to work as a labour inspector in the UK and saw in a textile factory that asbestos was harmful in any quantity. In 1930 it was demonstrated that it produced asbestosis, in 1955 lung cancer and in 1960 mesothelioma.

"Asbestos is a synonym death, a synonym silence, it is doing business at the expense of the lives of others, the intransigence of those who have the power... but above all, asbestos is a

struggle" Juanjo Basterra

Those responsible for the asbestos industry, who knew it, voluntarily concealed it. One of the goals of the first asbestos cartel created worldwide was to control technical and medical information, according to a recently declassified internal document. With the creation of the International Asbestos Association (AIA) later on, the objective was the same: to organize conferences (London, 1971) and courses among managers, with a strategy of collective reaction against research that multiplied the risk of asbestos. Disinformation has always been the effective weapon of dirty war.

Forty years later, companies ask for a kind of amnesty, arguing ignorance. “The victims have suffered a silence because mutual societies and governments have not been by their side,” says Basterra. Many times employers try not to relate to asbestos, because they know that working with asbestos is the ‘lottery’ of the disease.” They accuse victims’ associations and militants of judging the past on current knowledge. But this argument was tarnished by a ruling of the Spanish Supreme Court in 2012: companies are indebted to the safety of workers, above and beyond what the regulations of each moment require. They couldn't look the other way.

10 million deaths

Asbestos is a report praised by propaganda and censorship of counterinformation. It may thus be understood that 97% of patients diagnosed with asbestos in the Spanish State are unrecognized and unprotected. According to Puche, “this hard and invisible core is part of the conspiracy of silence”, unrelated to other European countries such as the French State.

The researcher has created an algorithm to quantify the number of people who will die of asbestos in the Basque Country. To this end, it has taken into account the relationship between asbestos consumption and cancer – a mesothelioma for 130 tons –, the life span of the mineral for 40 years and the period of onset of the disease. In this decade alone, 32,692 people will die each year in the world from mesothelioma, and considering the cases of asbestosis and lung cancer that must multiply from the scientific literature, he estimates that ten million people who were in contact with asbestos in the twentieth century will die. The World Health Organization is not far from that figure: asbestos will kill 107,000 people every year.

The Basque association of asbestos victims, Asviamie, says that at least 25,000 workers in Hego Euskal Herria have been in contact with the pollutant in the past and that "one third will die prematurely". A report commissioned by the Basque Parliament in 2015 for the presentation of the compensation fund notes that between 2019 and 2023, 507 annual pleural cancer pleurals and 350 asbestos mesotheliomas in the CAV could occur. In a guide on asbestos published by LAB it can be read that in Euskal Herria between 6,000 and 10,000 people can die from the disease of minerals, “depending on certain measurements”.

What is that if it's not genocide? Isn't that making systematic suffering and death happen? Genocide is behind an intention and a strategy, according to the United Nations Convention that was adopted in 1948. And in the 2014 trial against Stephan Schmidheiny and Eternit in Turin, it became clear that something like this happened behind the asbestos industry.

In that important trial Prosecutor Sara Panelli and he considered that the chiefs of Eternit “intentionally” concealed what they knew about asbestos: “The company’s senior management had complete indifference to the safety of workers, despite the damage caused by asbestos.” It was so clear that, on the third day of the trial, a judge compared Eternit's strategy with the plan for the deportation of Jews to Madagadascar by the Nazis in 1943. In those days in Turin, however, the power demonstrated the extent to which the shadow continues: the billionaire entrepreneur went unpunished – with the abolition of the sentence of 18 years in prison that corresponded to him – because the crime was prescribed. "The dead don't prescribe! ", "This is a shame! was heard aloud in the courtroom where the victims were sitting.

In any case, the sentence allows the head of Eternit to be prosecuted again, as he does not say that he is innocent. In 2015, a new complaint was filed against him by the relatives of the 258 victims who were murdered – and have not prescribed – between 1989 and 2014. How many men are responsible for death? Puche dares to say figures in his book: Eternists can have between 360,000 and 450,000 bodies behind them – the owners of Uralita between 23,785 and 37,630. “They could be tried in complete peace of mind at the International Criminal Court in The Hague,” says the investigator.

Like many others, Schmidheiny has wanted to cover his past through philanthrocapitalism. In 1994, it created AVINA, a foundation to “promote sustainable development” in South America, and years later made available to a society some of its companies worth $1 billion to fund the foundation. You have read it well: capitalism at the service of society. Schmidheiny has supported gigantic projects such as Ashoka, a new line of business linking social entrepreneurship and turbopatitalism, as well as Jesuit universities. The Swiss has had a direct relationship, for example, with the Berber theologian Luis Ugalde. The former rector of the Universidad Andrés Bello de Venezuela is known in the Basque Country and has been received by lehendakari Iñigo Urkullu himself in Ajuria-Enea, but it is not so well known that the pedagogical mission promoted by the Basque Jesuit Fe y Alegría was based on the benefits of the asbestos industry taking advantage of its friendship with Schmidheiny.

Pain of victims

Many of the victims who filled the Turin Court of Cassation were Casale Monferrato. In this Italian town of Piedmont, Eternit had until 1986 one of its main factories and for tens of years both children and adults transported it by train and after flying the trucks extended to the center of the town “white and light clouds that soon became a very familiar family”, according to journalist Giampiero Rossi in his book La obra della salamandra used the factory waste and the policy of filling the streets and streets. In this population of 34,000 people, more than 2,000 people have died from asbestos, not in vain is known as “the world capital of pain”.

One of the protagonists of the book is Romana Blassoti, a woman of almost 90 years old who is currently a symbol of the fight against asbestos. The husband who worked at Eternita died at the age of 61 due to a mesothelioma; six years later his sister died because her husband and son took home the deadly dust in their clothes; then a cousin who lived near the factory; and finally his daughter died to Romana, although she never worked with asbestos. This latest death caused great indignation among the citizens: “Romana was exhausted by pain and didn’t cry much,” says Rossi in the book. He still feels such anxiety when remembering. But then the only thing that really mattered was for the massacre to demand justice from other families in the village for the suffering it had caused.”

In the late days prior to his death he needed 400 ampoules of morphine for four days, through a pipe that was placed with a pump in his arm.

But in order to know the pain of the victims and their families, it is not necessary to go to Italy. In Euskal Herria we can find hard testimonies in any town, such as those collected by Juanjo Basterra in his book Cuatro Lunas. One of them is Begoña Vila, whose husband, Marcos Albitre, worked for 25 years for Renfe and Wagons Lits and was diagnosed with asbestos inhalation pleura cancer in the cars on the trains running. In the late days of his life, he needed 400 ampoules of morphine for four days, through a pipeline that put him in his arm with a pump: “Tears fell down his sore cheeks. I couldn't sleep in bed, I did it in the living room," says Vila in the book.

Albitre died in 2006 at the age of 46 and after his death “Begoña lived with great powerlessness the disregard of the company,” explains Basterra. However, after many fights, a hospital in Barcelona managed to show that her husband died of mesothelioma and after five years in the courts, with the help of Jesús Uzkudun of CCOO (see later interview), he had a favorable ruling. “The processes are long, it is true,” the journalist said. They spend many years from the beginning to the end and many affected do not see the end.” Basterra uses data from the office of the lawyers of Asviamie Nuria Busto and Blanca Ruiz de Eguino: in the processing of the associations there have been 113 firm judgments, 80 in favour, 17 against and in 16 cases they have reached an agreement.

Dark stories covered with stone slabs

One of the objectives of the Asbestos Victims Compensation Fund is to prevent the passage of this judicial suffering. At the request of the representatives of the Basque Parliament in the Congress of Spain, in 2017 the constitution of the fund was approved, but there is no lack of scepticism: “We will see what happens, because since November they are delaying the presentation of resources,” says Basterra. This fund would guarantee a minimum for victims who cannot resort to specific companies, either by the disappearance of the company or by indirect contagion to it.

Recently, the Spanish Supreme Court has issued a major judgment against Uralita for the alleged crime of contamination of neighbours in the Catalan town of Cerdanyola. The Col-lectiu lawyers' association had been trying for years to prove that the factory not only infected its workers and their families, but also those living in the vicinity. The ruling condemns the asbestos company to pay EUR 2 million to 39 people for the incidents.

But in addition to Cerdanyola, there are other places that have the dark history of asbestos covered with a slab. In the Basque Country, for example, Fibrocementos Vascos, S.L., worked in full Franco in the center of Altza, where there is now a sports club, which has generated dozens of concerns and concerns in the recovery of this industrial past. In the district of Retuerto, in Barakaldo, was the plant of Montero Fibers and Elastomeros, one of the fifteen largest importers of asbestos in the 1950s, 1960s and 70s of the Spanish State. Now there are only department stores and homes, but raising the slab is not difficult to see the ghost of cancer and hear the shout of the forgotten asking for truth and justice.

Fortunately, most industrial companies start to understand, after the many convictions, that a small exposure to asbestos fibres, without adequate respiratory protection, is sufficient to cause a serious lung disease that causes ten times more deaths than accidents at work, even... [+]