"Elbira Zipitria crossed many borders and I also told her story."

- Many times there are ideas that require a long journey; others, the ideas themselves are the ones that meet you. Something like this happened to the filmmaker Maider Oleaga (1976, Bilbao). Since then, there have been six years and so many hours of work, but in the end the film Muga, which is called Pausoa, has finished. The documentary tells the path he has taken to meet Elbira Zipitria, a pioneer in the world of education and politics.

When he returned from Mexico after seven years, a friend asked him: if he had a house in the Old Part of San Sebastian that he wanted to rent someone he trusted and if he was going to take him. When he saw the house, he nodded with his head. He knew beforehand that he had belonged to a certain Elbira Zipitria, but he did not care. He found out who Zipitria was and that this same house had been used as a clandestine school. He couldn't resist the temptation to tell a story in his turn. He has worked for six years. Meanwhile, he has been involved in two other projects: Directed The last site, requested by ETB, in Berlin, and has everything prepared to host the Kuart Valley film which has as its axis a Western made in the village of Kuartango.

What brought you to the documentation?

I started signing. I studied audio-visual in Pamplona and film direction in Madrid. I was educated as a fictional director, and then I did some work in Mexico as a director. But I didn't master the tools of work -- cameras, post-production -- I felt the need to get closer to film in a more artisanal way. I made a short in Bolivia with all those jobs within my reach, and that changed something in me. I still want to go back to fiction, but before I wanted to have more to do with the documentary and with reality. These documentaries have served to deepen my relationship with film.

“Bringing the past to the present helps us understand many things today”

Those who were my teachers learned with Elbira Ziptria, and they gave us more or less information about it. But if you ask here or there, nobody knows who it was.

For all the work he did, it's nothing known. Almost seven years ago, I started doing research, and there was almost nothing on the Internet. There's some weird book they did to him when he died and others who talk about pedagogy. But there's almost nothing about his life. I was researching for the first two or three years, and I ended this process with a lot of saturation. To understand the moment he lived and all the things he did, he had to scrutinize a lot. Language, politics, education… He worked in a thousand fields. This has led me to meet many people: their friends, their students… To a large extent, I have felt in the world of Elbira.

You have stressed that the boundary between fiction and reality is delicate.

It is a very broad issue. For me, there's always fiction, even in a documentary. As I entered my documentary character, I created a fiction. In this case, Elbira Zipitria is a historical character. However, the resources I have had to approach the person are imaginative: the memories of others and my relationship with an already dead person. That's also noticeable in the form. I didn't want to make a biography: although at first I did an exhaustive study, then I was released. The search has not been so historic, but personal. I wanted to know what that woman was like and why that had happened.

You, too, are part of the documentary. When documentaries are made, the figure of the filmmaker who enters a search is common. Did you feel comfortable in that role?

In this film it was essential that I appeared. A few years ago, out of shame or something, I doubted. But being honored with myself, it was inevitable. When we started recording, I forgot about the discomforts. I had to do it, and it's enough. We recorded it for three weeks in my house, in a group of five people. That Maider who shows up there is a character. It's me, but it's not me. He's a character with a conflict. And I've put it at the service of the movie. I've also put the voice off, and then I've felt more naked.

“The focus should also be on

works outside industrial cinema,

but there are many aspects

to be touched on”

The title in the process has also changed: The border is called Paso now.

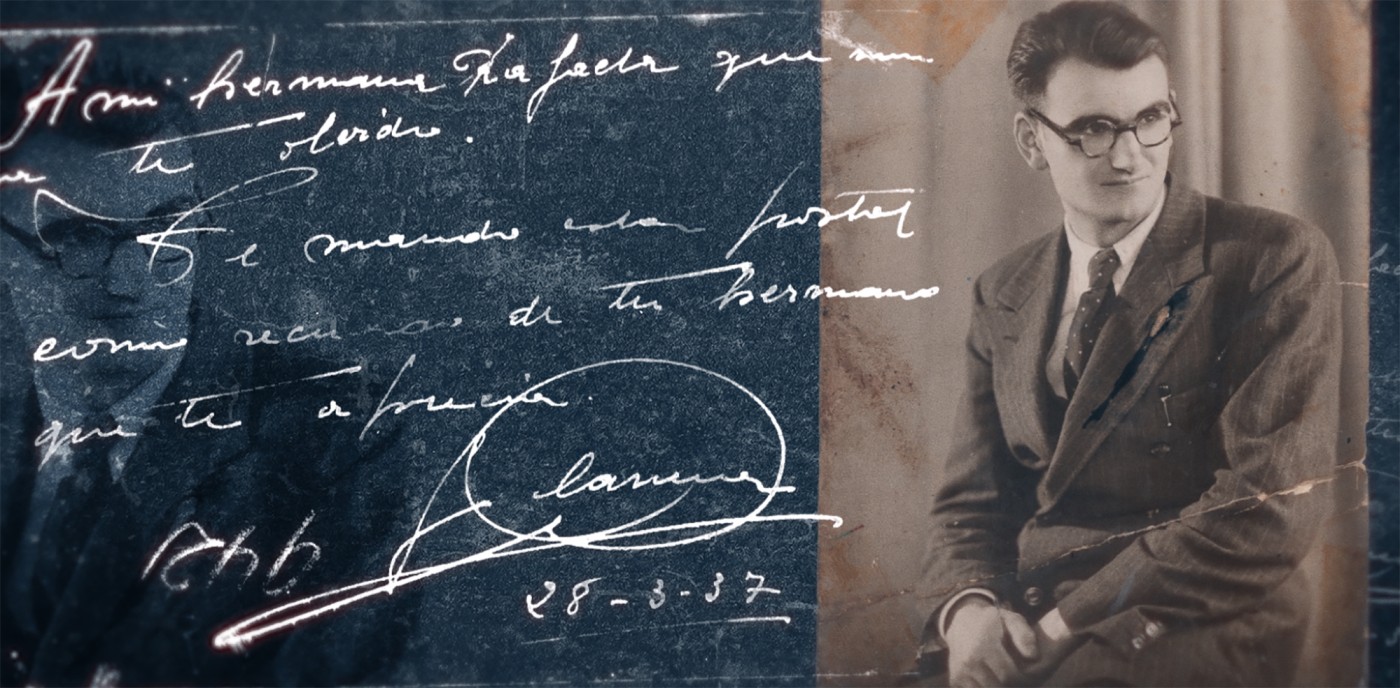

When the project started, I named it IRA26-2. His nickname was Ira, and the address of the house is 26-2. For me, the house has a lot of weight, and that's why I gave it that name. In addition, the first indent consisted of 26 chapters, in which the original indent was projected. As new versions are being made, the one of the 26 chapters becomes meaningless, and that number does not appear in the film either. The phrase “Muga is called step” was used by a friend of Elbira Zipitria when she spoke to me. This is a phrase extracted from a poem by Pedro Mari Otaño. I pointed it out because I really liked it, and then, when it came to riding, I saw that it made sense. I think Elbira overcame many limitations in his life, and I too did the film: first, the frame itself; that it appeared in the film.

While working with the documentary on the cistern, you’ve also made the movie Past a Berlin site. At the request of ETB you have approached the times that the Lehendakari Agirre gave in Berlin. Has it been difficult to combine the two jobs, one on request, another very personal?

It was very well for me to undertake the task of ETB. He was already quite saturated with Elbira. I spent a year doing The Past in Berlin, and five months doing it in Berlin. I think he has favored the Step called Muga. The way to give the film has been very difficult, and at that distance, I have seen it clearer.

The two films tend to get to know the historical characters from the people of today.

This indicates my conduct and my interest in the past. We have to do historical research to understand those contexts, but I think we always have to approach the past from the present. In the case of Elbira it has been particularly investigated since now, from here. Bringing the past to the present helps us understand many things today. Of society, of our identity… It is essential to move forward. So I'm trying to approach these historical characters personally. In Berlin there was also an effort to imagine what Lehendakari Aguirre could be like through the people of today. That is what they have to do.

“If we get used to connecting cinema only to Hollywood’s model and entertainment, it’s hard to see and enjoy a movie with

another feature.”

What is the language of your work? As far as Elbira Zipitria is concerned, has the film asked you to do so in Basque?

I studied in Madrid and then spent seven years in Mexico. I've worked a lot in Spanish, and it's called Muga. The step has been the first one I've ever done in Basque. For me, the relationship with Euskera has changed a lot with Elbira, it has brought me a lot closer to Euskera. I knew it before, but I wasn't at the center of my life. Entering the elbira world, I understood, as well as my bodies, that it is a choice, and that you decide to live like that or not.

It is often said that documentaries are made in the assembly. But it is often decided, though, whether or not a film is advancing in search of funding, when mounting is still a long way off. Do you feel comfortable with this way of doing?

We must admit that this is the case. Sometimes you feel like you're lying, because when you write the idea, you know there's still a lot of decisions to make. But whoever reads the dossier also knows that this is the case. It's not easy for me. But I think it's a nice exercise, because it forces you to imagine the movie. It is also true that I have a lot of idea in the drawer, and it will still happen to me. But I think you have to be very clear that you believe in a project and want to move forward. If you're not convinced, it's going to be very difficult to make the way. You need that force because the process is very difficult and long. In the case of the Paso it's called Muga, I already knew, with funding or not, that I wanted to make the film.

Errementari and especially Handia have been very successful. Does this also benefit the filmmakers who work on a very different path?

Success is, of course, satisfactory. But normally the most spectacular movies are big. There are many kinds of movies, and the public doesn't know many people who are working. There's a lot of stuff behind it. The focus should also be on work outside industrial cinema, but many aspects must be taken into account. In education, for example, film has very little space. If we get used to connecting cinema only to Hollywood's model and entertainment, it's hard to see and enjoy a movie that later has another function.

Making a movie about a movie is your next project: Kuart Valley.

That has also been a coincidence. I went to the town of Kuartango randomly, and there I learned that they had made a western. I thought there was a movie there. Later, Mario Madueño, producer of The last site of Berlin, called me telling me that a producer in Madrid had heard about the film and that they wanted to do something. They were looking for a director, and I said yes. We are still in the initial phase, but the goal is to tell how the film was made Something more than dying in seven years, amateur and with the help of the citizens, adapting all the people for it… The process of immersion will start from March and then we will decide how to count it and represent it. That will be the challenge.

Itoiz, udako sesioak filma estreinatu dute zinema aretoetan. Juan Carlos Perez taldekidearen hitz eta doinuak biltzen ditu Larraitz Zuazo, Zuri Goikoetxea eta Ainhoa Andrakaren filmak. Haiekin mintzatu gara Metropoli Foralean.

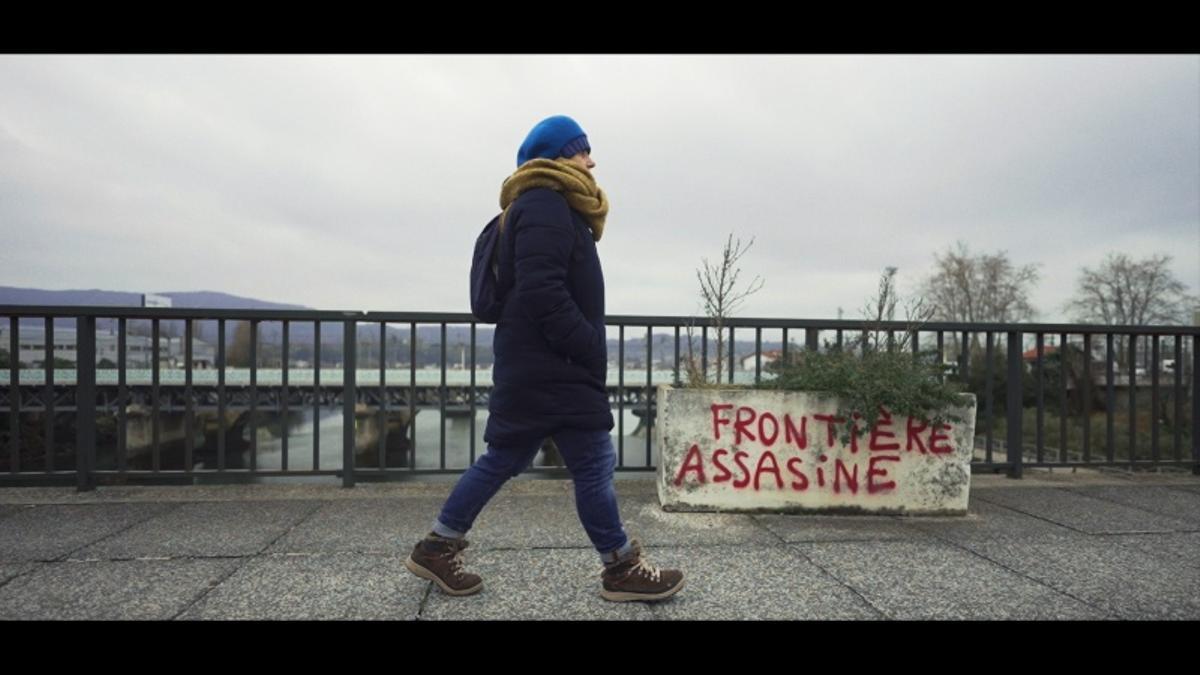

Projection of the documentary Bidasoa 2018-2023

Where: Martutene prison, Donostia

When: Friday, 22 December, 16:00h

Available as a network: Perfect on the platform

------------------------------------------------

It's Christmas. Friday after lunch. Let us go through the long... [+]

FIPADOC Nazioarteko dokumental jaialdia berriz heldu da Miarritzera. Urtarrilaren 19tik 27ra ospatuko dute, eta seigarren edizio honetan «Italia eta Afrika» izanen dira protagonistak.

Hands have a varied symbology. With hands the world is driven and with strong fists the command is supported. Power also fights with fists, picking fingers and raising hands up. Hands are necessary for those who have always been the losers of life, for that alone has been an... [+]

Lana finantzatzeko diru bilketa abiatu dute; ahalik eta gehien zabaldu nahi dute ikus-entzunezkoa, protagonistak sufritutakoa ezagutarazteko eta torturak salatzeko. Bi arnas kontatzen dira, torturaren eraginez itxi gabe dauden bi zauri: Sorzabalena eta haren ama Maria Nieves... [+]