"March 3 was the biggest crime after Franco's death."

- Every year is March 3. Five deaths in Vitoria-Gasteiz and hundreds of wounded, most of them bullets, in 1976. Imanol Olabarria came to Vitoria to work a few months earlier. Between November 1975 and the destruction of March 3, he participated in the protests, assemblies and mobilizations that took place in several factories. Moreover, he was one of the agents.

Apaiz langileetakoa izan zen, Trapagarango Zugaztieta auzoan ari zen 60ko hamarkadaren hasieran, eta Gernikan ere bai geroago. Zamorako kartzelako apaizetakoa izango zen, lehenago ihesi joan izan ez balitz. 1975eko udazkenean heldu zen Gasteizera eta barru-barrutik bizi izan zuen Martxoaren 3 haren aurreko borroka.

You were in Vitoria in early 1976.

Yes. I came from Bilbao and tried to get into Michelín. I remember, at five o'clock in the morning, at the door of the factory, doing the tests, doing the tests and handing over to the appropriate person. I had to try to fool those in the factory by saying it was a pawn. I got the test and my managers came: “You didn’t answer this question,” “I think it was going to be an intuitive answer.” I regretted having said that. The pawn doesn't use the intuitive word. Of course, I didn't fool you. “Unable to be a pawn,” I received the letter. They told me that in another factory, called Cablenor, they needed staff, they didn't pay much, but they got them without any kind of test or control. However, they asked for military service, but I had been a cure and I had not done military service. So I told them it was from the Cupo of 37. And to work.

At the beginning of January there were several strikes in Vitoria-Gasteiz.

They did not come from scratch, they were also not the accounts of four demagogues, nor the initiative of a party or union. When people start to wonder about 3 March, they want concrete answers, but, on many occasions, they forget the social situation, the struggle then. After Franco’s uprising, after the dictatorship, the meeting was banned: there was no party – except Phalanx – there was no union – but Vertical, of the regime – there was no right of assembly or demonstration. After World War II, people expected the allies to knock Franco down, but that wasn't the case. Even worse, in 1953, the United States came into contact with the Franco regime and the following year the Vatican did the same. In 1955 Spain was recognized as a member of the UN.

In the 60s of the last century, what was the situation in Vitoria-Gasteiz?

Many companies came here at the time, from both Bizkaia and Gipuzkoa, and from Eibar, Elgoibar and Oñati. People also came to work in Vitoria-Gasteiz in the small towns of Álava. And also from Extremadura, Galicia and Andalusia. In Cablenor, for example, most of the people who came from Extremadura were from Extremadura. At that time, they worked six days a week, eight hours a day, the worker even included overtime, and yet the wage did not live. Fixed expenses of one and the increase in the consumer price index of the other, the worker had a low purchasing power.

When he started working in Cablenor (Vitoria-Gasteiz) in November 1975, what was the weather of the company?

My peers had worked as labourers, and they had no awareness of struggle. Some of the workers had police officers or civil guards among their relatives and talked about them normally; unlike those here, I mean, because those here knew the repressive forces. His colleagues did not have a firm opinion about the employers, or about the trade union or the press. Despite this atmosphere in Cablenor, fifteen days before Franco's death, we began to gather in Vitoria-Gasteiz several people. Because we didn't have the right to meet, we would meet in some bar, talking. In these meetings, there was no shortage of disputes, as everyone wanted to show their acronyms.

What were their acronyms?

I didn't have acronyms. It was marked by the strike of the Etxabarri Bands [initiated in November 1966, which lasted 163 days], in which the assembly ordered. It seemed to me the most enriching thing. Everything was decided in the assembly. For example, as soon as we went out to the Cablenor strike, Forjas Alavesas, Mercedes and Aranzabal were also on strike. In the end, we were twelve companies on strike. We belonged to various sectors, but we went on strike at the same time. This was the characteristic of the strikes in Vitoria-Gasteiz: we broke the legal regulations at the time, since each sector had a month of negotiation of the agreement. In Vitoria, on the other hand, we left together.

You were on strike for four days.

In the morning, we went to the factory and agreed to enter the new pavilion that was empty. We didn't work. After four days, the company closed the factory. However, this was not the first case, as other factories were in that situation and, in the meantime, took the church in San Francisco. We also took this path in our company and entered the church of Judimensiondi, against the will of the priests. But we, ours, from respect, but ours. We started making open meetings so that the people of Vitoria-Gasteiz know from a good source if they want to know anything. We knew the police were sending their secrets, but we continued.

You were on strike, with the factories closed, and you were locked in the churches of Zaramaga and Judimendi.

And in the church of Judimensiondi the workers of the furniture factory Apellaniz were also closed with us. Every company on strike met every day. The assembly helped us all a lot, because we were afraid. We exchanged information there, we analyzed the problems. Each assembly became a school, a school for workers between the ages of 20 and 65. Every day we talked about something and then we voted. Those meetings helped us a lot. At the same time we were also making demonstrations in Vitoria-Gasteiz, although there was no right to do so. The police began to charge the demonstrators, arresting the workers, who have been arrested. And when the police arrested a worker, or the employer fired a worker, we responded to all the companies that we were on strike. In fact, on Thursday afternoon we began to meet all the workers on strike in the church of Zaramaga, and that meeting was attended by the committees of representatives of all the companies on strike. We workers form a common front in Vitoria-Gasteiz, a unitary list of demands. When the employers accepted our economic demands, we did not, until we took the workers who were laid off again. And then, when the dismissed were received again, not until the arrested were released. When the situation in one company was resolved, the knot of another factory had to be released. We put freedom before any negotiation, all workers at once. We were together, but the employer wasn't.

Thus came the strike of 3 March 1976.

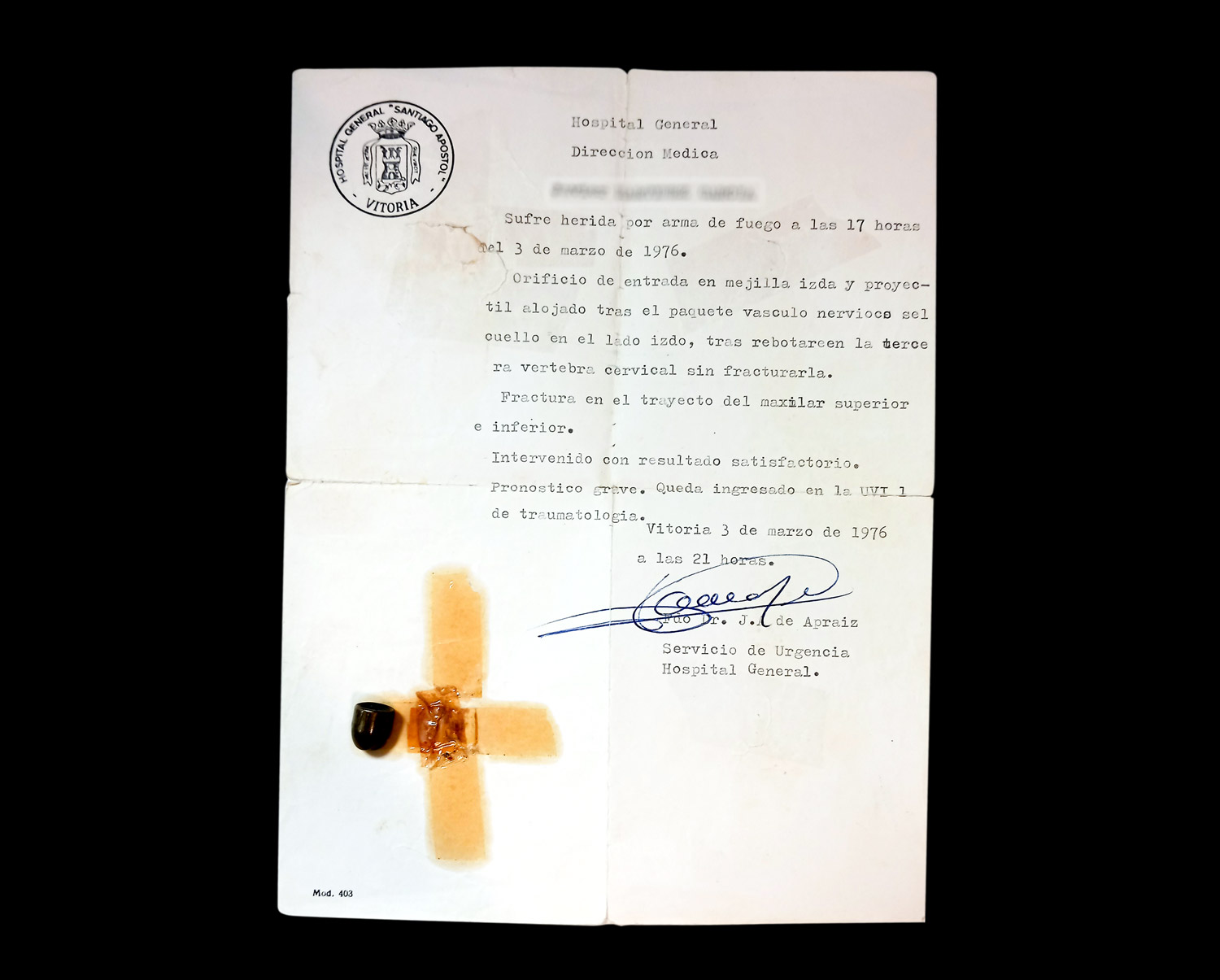

The joint assembly on Thursdays convened three times the general strike called by the central government for this year. The first had no echo; the second had more; the third was March 3. On that day, the police opened fire in the morning. Injured in the Ormaetxea of the town of Urbina. Andoni Txasko was also severely beaten that morning in his only eye. After lunch, before the Church of San Francisco meeting, the factory representatives met in the Church of Judimensiondi to prepare a joint meeting. When we finished ours and went to the church in San Francisco, we saw that the police had the temple surrounded. We threw ourselves into stones, but it was in vain. Then, it is known, the church workers were attacked and, upon leaving, the police started shooting and shooting.

"Shoot, shoot, shoot people! you hear it in the words of the police.

As we know, Agirre, manager of Forjas Alavesas, moved to Madrid with other entrepreneurs. It was four or five. They met with the Minister of the Presidency of the Government of Spain, Alfonso Osorio, and three days later the Minister of Government of Spain met on 3 March. According to our interpretations, after hearing the one I had heard at that meeting, the Government issued an order to shoot so that there would be nowhere else what happened in Vitoria-Gasteiz, which was intended to kill workers.

Three days later I was in Madrid.

With date 8, Jesús [Fernández] Naves and I had an invitation to go to a radio station in Bilbao to tell what happened in Vitoria. That day we had a meeting in the basement of the church of the Pilar, and an employee came and told us that the police knew the meeting. We left. Three hours later, on the street, I was picked from behind. They tied my hands and put me in a car. I was held there half an hour before Jesus was also arrested. I went to the police station and stopped with a couple of blows, but not with torture. Threats. The police officers were angry. “We take you to the swamp, you swallow all the water!” Detained, standing, facing the wall, and two hours later, in Madrid, he has been arrested.

The indictment was sedition.

We were held at the General Directorate of Security, at the Puerta del Sol, in Madrid. Three days there and Carabanchel. While we were there, we learned that we were accused of sedition. “And what is that sedition?” the lawyers answered. “Attack on State security.” Like that! The Spanish minister, Fraga Iribarne, and his colleague, Martin Villa, intended to set the workers in motion. They thought they were going to roast the workers, but they didn't believe it. The following day, several protests took place and the police killed one worker in Tarragona [Juan Gabriel Rodrigo, 6], then another in Basauri [Vicente Antón Ferrero, 8] and another in Rome [Mario Marotta, 14] in the solidarity mobilizations with Vitoria-Gasteiz. The authorities then made a different reflection: “We cannot walk like this, we are throwing wood into the fire.” And they changed the speech. We were in jail and we didn't fully understand it. Then, upon leaving, we realized the change.

What was that change?

Discussion sessions were suspended and briefings were set up to impose the slogans of political parties and trade unions. We were called to vote and since then we left the leading role in the hands of others. We went from being against power to shouting “the workers to power.” We refuted the strikes and invented “days of struggle”, a day and a weekend. The repressive forces changed the color of the uniform and began to call it “law enforcement workers.” We went from the resistance fund to the reserved funds of the State and lost autonomy. Those of us who work together submitted to acronyms, sectarians. At a time when the Boards of Delegates were rejected, we now have representatives with a four-year privilege. Before it was a vertical union, then there were seven or eight “vertical” unions, they are now each for their interests. “Social anesthesia,” said Fernández Durán.

What do you say about the fight then?

I have a sweet sour cocktail inside. We had a dream of freedom, we wanted to end that vertical union, we wanted to control working conditions. We fought for the dignity of the workers, we set up assemblies to make them spaces for debate and decision-making, we set up committees for spokespersons, so that we reject them at any time. We are trying to work for the equality of the workers, for the linear increases of money. We called for economic improvements and better working conditions, but we prioritised the readmission of redundant workers, the release of detainees and the maintenance of their jobs. Three months of struggle.

It takes a critical view of the events currently being organised around 3 March.

A floral offering is made and a tribute, which I respect. It is reminiscent of the five dead, but not of their dreams and forms of organization, which can be a way of putting a stop to the struggle. It's certainly not the intention of unions and workers, but I think the will of some organizations is that, like saying they were killed, "Beware!" Then came the era of anesthesia of society that says Fernández Durán [anti-globalization movement activist]. They designed ways to steer the labor struggle, so that there would be no harm to capital. Today, I think and would say that since the death of Franco, and until now, it is the greatest crime we have known: more than five deaths and more than a hundred wounded, before thousands of witnesses and not charged.

“Puerta del Solen, Madrilen, polizietako batek galdetu zigun: ‘Zer dela-eta ekarri zaituzte Gasteiztik hona?’ Eta azaldu genion, ez baikenuen ezkutatzekorik. Eta poliziak: ‘Gasteizko Michelinen jardun ninduan lanean. Anaia diat hango lan-batzordean. Ke beltza sailean ari ninduan lanean, sail toxikoa, ezin nuen eraman, osasunagatik, eta polizia sartu nintzen. Baina hau ere ezin dut eraman, uztekoa naiz. Zigarro bat nahi?’ Komunera eraman ninduen, erre nezan. Eta polizia negarrez!”.

“Emakumeek eraman zuten borrokaren zama astunena, ikusi ez zena. Eurek eutsi zioten familiaren ekonomiari, eurek sufritu zuten gehien eguneroko garraztasuna, eurak joan ziren ikastolara eta banketxera ordainketak atzeratzeko eskatzera, eurak izan ziren erresistentzia kutxaren zutabe nagusiak, eurak manifestatu ziren eskirolen kontra. Emakumeek ordu arteko moldeak apurtu zituzten eta mobilizatu ziren”.

Hiru bideo dira (albiste barruan ikusgai). Batak jasotzen du, grebak antolatzea leporatuta, Carabanchelen espetxeratu zituzten Jesús Fernandez Naves, Imanol Olabarria eta Juanjo San Sebastián langileak espetxetik atera ziren unea, 1976ko abuztuan. Beste biak Martxoak... [+]

49 urte eta gero Espainiako Poliziak Gasteizko Maria Sortzez Garbiaren katedralean eraildako bost langileak oroitu dituzte beste behin astelehen arratsaldean. Milaka pertsona batu dira Zaramagatik abiatutako eta katedralean amaitutako manifestazioan. Manifestari guztiek ez dute... [+]

Martxoak 3ko sarraskiaren 49. urteurrena beteko da astelehenean. Grebetan eta asanblada irekietan oinarritutako hilabetetako borroka gero eta eraginkorragoa zenez, odoletan itotzea erabaki zuten garaiko botereek, Trantsizioaren hastapenetan. Martxoak 3 elkartea orduan... [+]

1976ko martxoaren 3an, Gasteizen, Poliziak ehunka tiro egin zituen asanbladan bildutako jendetzaren aurka, zabalduz eta erradikalizatuz zihoan greba mugimendua odoletan ito nahian. Bost langile hil zituzten, baina “egun hartan hildakoak gehiago ez izatea ia miraria... [+]

Martxoaren 3ko Memoriala hornitzeko erabiliko dira bildutako objektuak. Ekimena ahalik eta jende gehienarengana iristeko asmoz, jardunaldiak antolatuko ditu Martxoak 3 elkarteak Gasteizko auzoetan.