The civil society struggle in Lebanon comes from the rubbish.

- Lebanon is a small paradigm in the Middle East. Being the smallest and most plural country in the region, all the conflicts and crises in the environment affect it. Thus, the Lebanese have become accustomed to living in a situation of instability in the country. In recent decades there have been numerous conflicts, interventions by foreign armies, ethnic and religious clashes... In 2015, tens of thousands of people were threatened by the fall of government on the streets of the capital. Few had foreseen the reason: the waste management model.

Until 2015, most of the waste from Lebanon was shipped to the Naameh landfill, that is, almost all the waste from a country of three and a half million inhabitants was collected in one place. As if space and time were unlimited, the authorities did not seek solutions until the landfill was completed. Politicians were unable to agree on the location of the new landfill and the shortage of both collection and recycling infrastructures caused waste to accumulate rapidly in Beirut and in the vicinity of the Sierra de Lebanon. About 150,000 protesters participated in the protests in August of that year, the largest protests in the last decade.

In Lebanon waste management has been the excuse for fighting an entire corrupt political system.

Many took a big surprise, as an ecological fact caused people’s outrage, not ethnic or religious clashes. However, waste management was only an excuse to oppose an entire corrupt political system. And it served to change the political map of Beirut. Those who were fed up with sectarian politics created Beirut Madinati (my city, Beirut), a party that wants to change the politics of the whole country through an environmental political agenda. He is currently in the capital.

The party response was always indifferent; they hoped that the problem would be solved by opening two landfills on the coast. The first was inaugurated in Burj Hammud, an Armenian neighbourhood located north of Beirut. The other, south, next to the airport, and even if it looks like a bad joke, on a beach called Costa Brava. The two landfill sites survived over several months, but remain open after two years. Receiving the old in Lebanon.

The mobilizations of two years ago were the result of several decades of negligence and two models were opposed: selective collection vs incineration, a debate that is well known in the Basque Country.

Waste Coast

Burj Hammud and Costa Brava were exceptional measures, as explained by Ziad Abi Chaker, leader of the Cedar Environmental group and promoter of the Zero Zabor Libano platform, which he described as "absolutely unusual". The Lebanese are clear that landfill policy has no future and are looking for new models.

Many proposals have been made, but Abi Chaker believes they will continue in the same direction until the model of politics is changed: "Most parties support the incinerator project, because it is a way to continue speculating. As long as waste management is a monopoly, the economic benefits will continue to be prioritised.”

The two landfills will continue to be filled until they overflow. Burj Hammud is one of the most populous neighbourhoods in Beirut, and as sanitation deteriorates considerably, the fires caused by the neighbours are becoming more and more frequent. The landfill of the Costa Brava, for its part, has put at risk the viability of the airport, which accumulates over a hundred streets. The risk of collision with aircraft engines has led to the fact that they have been forced to take action on several occasions. Acoustic alarms have ceased to be effective and have begun to bury the remains of the Costa Brava, which has further blurred the coast.

Symbol of a management crisis

The two landfills are nothing more than symbols of the crisis, as Lebanon itself has become a large landfill. It has 10,000 square kilometres – half of the Basque Country – three and a half million inhabitants and a varied geography. Mediterranean coast, cedar forests, mountains 3,000 meters high and desert. On the road from Tripoli to Tyre (163 kilometers), thousands of plastic bottles are piled as blue as the sea. In addition to the cities, in any town in the interior you can see the land used for the dumping of waste.

Chaker believes that the attitude of citizenship should be much better. In his view, the lack of education means that “most complaining do not recycle.” “There is still a lot of work to raise awareness; on the other hand, those who want to recycle have few resources.” Recycling is a matter of will in Lebanon. Everyone has to pick up, sort and take to the recycling area. Colourful containers are scarce and hardly found in the slums.

Overpopulation does not help either, and the situation of millions of refugees is particularly serious. Since 2011, Lebanon has hosted 1.5 million Syrian refugees, according to data from the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). However, since 2014, no account has been taken in order not to enhance the political balance of the country.

On the other hand, we cannot forget the Palestinian refugees who have been in Lebanon since 1948. In both cases, the lack of waste management has led to serious hygienic problems and an increase in the number of diseases. In the Shatila refugee camp, for example, some 40,000 people live in half a square kilometre – data must be taken with care because they vary greatly – according to the UNWRA organisation, which is responsible for Palestinian refugees in the Middle East.

Decentralisation solution

The Cedar Environmental Association of Abi Chaker proposes a local response to the problem: “If each region managed its waste, the system would be much more efficient and corruption would be reduced.”

The fact that waste from all over the country is subject to a monopoly is a cumbersome and slow system. Lebanese politicians do not take into account the general interest, but that of their respective communities. Environmental agents believe that the issue of waste will become more complicated if this sectarian political system is not changed.

Ziad Abi Chaker, however, goes beyond decentralization, as in recent years he has made a determined commitment to selective collection. The entrepreneur is known as Mr Zero Waste, because he believes in the possibilities offered by waste: “My success comes from the garbage.”

Abi Chaker is very critical of states and public institutions. The role of the State is to protect the welfare of the population and to guarantee human rights, but it believes that in Lebanon politicians are opposed to that possibility. He says that change has to come from the bottom, “when parties ignore people’s requests, civil society has to improvise.”

Private initiative alleviates the disease

At the moment, attempts at solutions come from the private sector: there are cooperatives and companies promoting selective collection throughout the country.

Curiously, the system that seeks the welfare of society is the result of private initiative. Cedar Environmentale works in partnership with municipalities. The effectiveness of the system is palpable, since in the city of Beit ed-Dine, in the Chouf region, the waste accumulated in the street has been drastically reduced, the rates of garbage have been reduced and many jobs have been created.

Cedar Environmental is not the only one who has opted for change; cooperatives and companies that promote selective collection have emerged throughout Lebanon, including Recycle Beirut, one of the most prominent social enterprises. It works with Syrian refugees and refugees from other countries.

The waste crisis in Lebanon has shown the two sides of the coin. On the one hand, the ecological and social consequences of irresponsible management are obvious, and the authorities do not seem to be going to change much. On the other hand, the Lebanese have known the power of civil society, and many have shown that they are prepared to assume it if they do not receive the support of the State. The incinerator’s project is moving forward in Lebanon, and opposition from a large part of civil society is against it. Two years ago, it was demonstrated that citizens could leave government. It will have to be seen what response they will give to the incinerator and what can be learned from it.

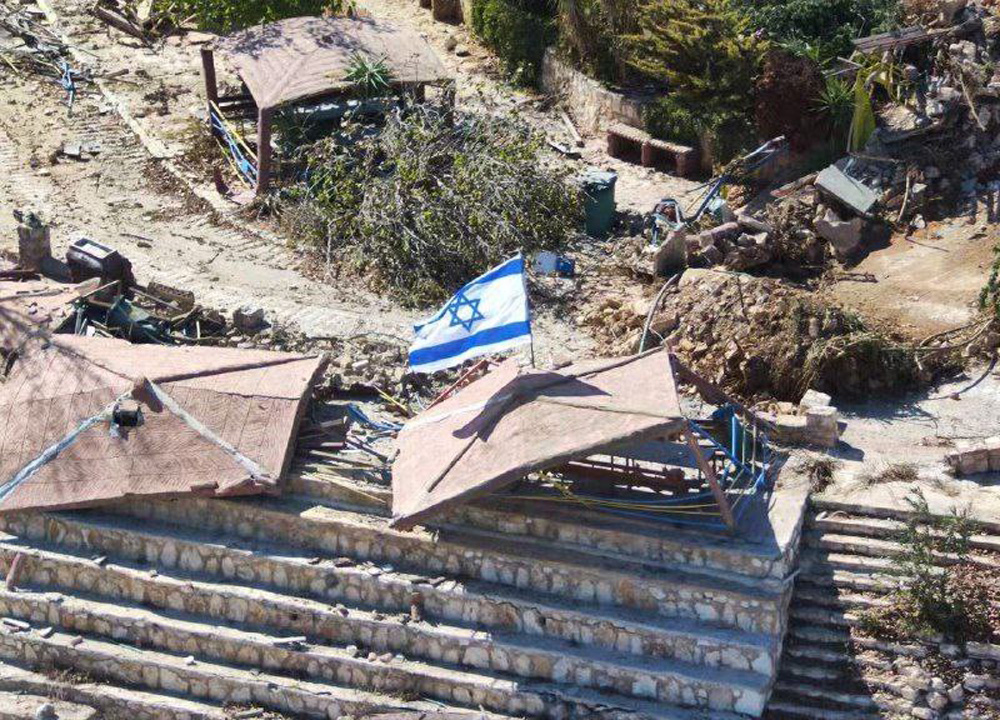

On the pretext of leaving Hezbollah out of play, Israel has attacked Lebanon, which has been rejected. As a result, small Switzerland in the Middle East has been placed in the media spotlight, but remains an unknown country. In ancient times it was the origin of an important... [+]