How Lafarge, in addition to cement, has ignited labor law in Greece

- Work contracts without health and social security, predominance of private employment agencies, contracts for days and hours, forced days without pay, redundancies without limit, constant wage cuts... How has this brutal precariousness of workers happened? It was already known that the employers of large companies have promoted the strategy of oxidizing the labour law of each country. In Greece, even with documents, it has been seen how a multinational has been driven by it.

“In Greek public opinion, the fact that the country’s labour legislation has been brought down under pressure from lobbies has spread. So far, however, there was no evidence to corroborate it. A November 2011 e-mail shows that the French cement multinational Lafarge, which has already been involved in several scandals, successfully intervened in the historic reform of the working code that the Athens Government then decided.”

The journalists Benoit Drevet, Leila Minano and Nikolas Leontopoulos, who work in the collective Ryanair-Europe, have given the news: “How Lafarge, a cement builder, called for and managed to break down Greek labor regulations.” It is composed of nine journalists from eight different countries who have started this work from confidential emails that the Greek newspaper Efimerida ton Syntakon was able to obtain.

To focus the issue at the time, he recalls that Prime Minister Social Democrat Georgios Papandréu fell from his post in 2011, crushed by the debt crisis. By then, Papandréu ordered Greece to submit in a referendum a very tough economic plan to restructure its external debt. In those months there was talk of the possibility of Greece coming out of the euro. However, Papandréu left office under pressure from both sides.

While everyone was looking at the parliamentary game, the economic forces, which the modern now call real powers, show how the emails of Lafarge President Pierre Deleplanque were going, the Dutch Bob Traa, the representative of the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

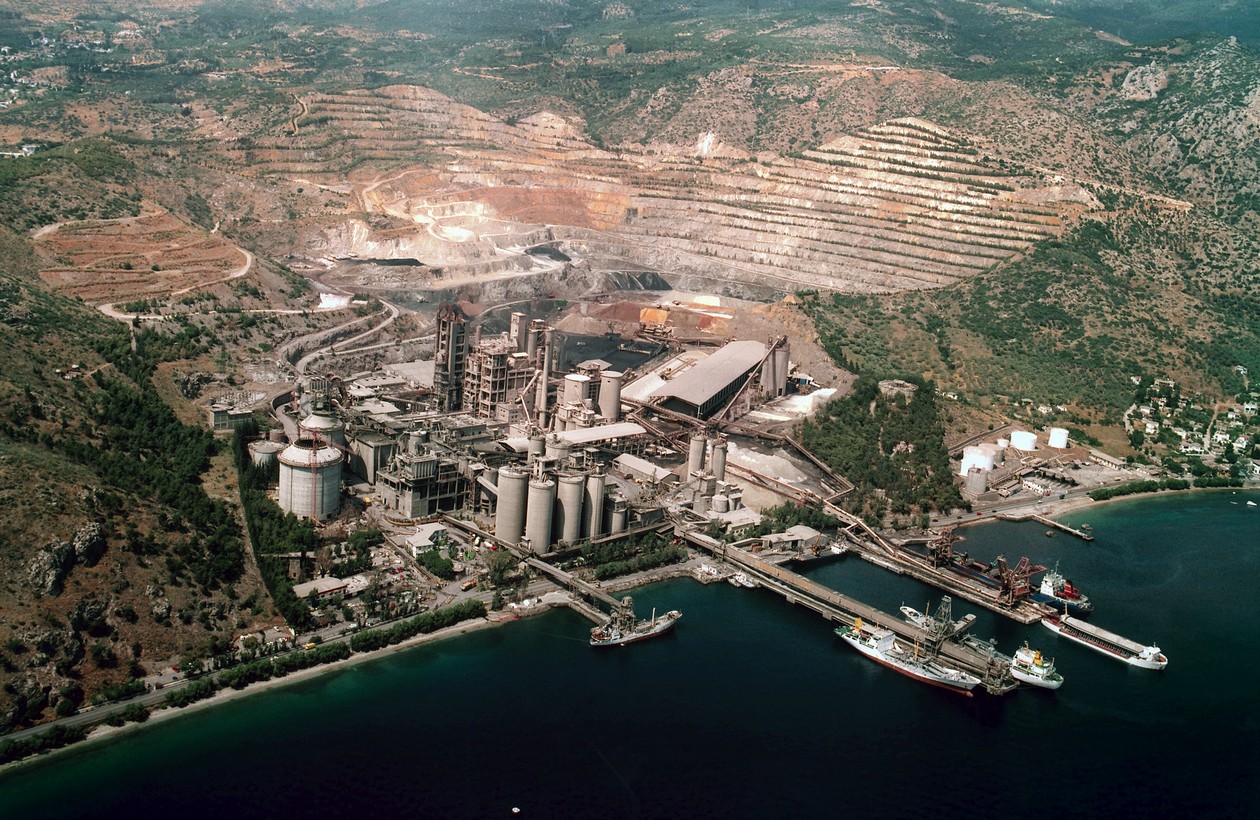

Hertrailers-Lafarge has 1,800 employees in Greece, sales of EUR 422 million and returns of EUR 41 million. It has three cement factories, one of them in the municipality of Volos, the largest in Europe, with its own port next to the export of cement by sea. 100% belongs to the French multinational Lafarge-Holcim: With 100,000 employees, their sales reach EUR 25 billion in 100 countries worldwide.

Lafarge’s leader, in his message to the bureaucrat sent by the IMF to involve the Greek economy – in addition to asking for the names of the most responsible people who carry the Greek dossier in the European Commission – says: “As promised, attached to this document summarising Lafarge’s position on the most urgent structural reforms in Greece.” It seems to the multinationals that four measures should be applied.

First, to replace the institution of mediation in conflicts between adults and workers established by Greek law, with the creation of new committees composed of well-known employers and non-political professionals to minimise the power of workers in mediation and to facilitate measures on the minimum wage.

The second demand is to make the conditions for the expulsion of workers more flexible, since those who are excluded in the way the laws are at that time (2011) have too easy to go to court. This simplification of redundancies, announced by the owner of Lafarge, should bring immediate benefits to companies, to the Greek State in debt and, of course, to the workers themselves.

Personnel dominance measures

The third measure that the multinational is asking for for in Greece is to abolish the sectoral conventions and confine them to each of the companies. Finally, leave the company fully entitled to the expulsion of workers due to economic loss.

Throughout 2012, all Deleplanque’s requests became laws, within the second plan to save Greece. The European Trade Union Institute (ETUI) has summarised that “these structural changes have resulted in the fragmentation and collapse of collective bargaining, the drastic fall in wages – the minimum wage in Greece was lowered from 751 to 568 in 2012 – and the reduction in social security income”. And, as if that were not enough, the institution that mediated in labor conflicts was left without strength.

In 2014, El País and the Wall Street Journal published some of the IMF's internal roles, where the team in Greece admitted that private companies proposed reforms to Greece with restrictions, privatizations and other violent measures that would then apply troicas.

What have these reforms brought in since then? A report released in October by the Greek Confederation of Workers reveals that the situation of the Greek economy, not to mention that of workers and ordinary people, is truly dramatic, unable to think of the great shipwreck of 2013.

Investment in Greece is 63% lower than in 2008, when the world was plunged into the biggest economic crisis of the last 80 years. “It is estimated that we will not return to the investment level of 2008 until at least 2033.” Consumption is 23% lower, “and it will not increase with the austerity measures we have today if no marginal measures are taken in jobs and wages”.

Unemployment rates have also tripled, the 99.000 unemployed in 2008 have now been 267,000, while in 2017 the unemployment rate is officially 21%. These figures do not take account of the large number of workers in black jobs or other fictitious jobs. On the other hand, the union has warned that all those who have contracts of 8 months a year with an EU aid programme are excluded from these figures.

The increase in precarious jobs has also led to significant wage changes, as the average earnings of temporary workers in 2016 were 397 euros.El 34.7% of full-time contract workers and 42.13% of those on hourly contracts charge less than the minimum wage, up to 586 euros. As a result, more and more workers are living below the poverty line. Meanwhile, the state has made brutal cuts in social aid, as well as in public services.

Keep Talking Greec, who closely monitors Greek news, wrote that “in a Greece marked by unemployment and austerity, wages have collapsed. Employers want to spend as little as possible on wages, workers are forced to accept unthinkable businesses before the crisis. The bosses, without shame, ignoring each law, offer them a peanut with this ultimatum: ‘If you want, leave it in another way’. This is the blackmail that the desperate unemployed cannot reject.”

.jpg)