An unexpected visit to Rafael Chirbes

- Settled an old debt, we have been at the house of Rafael Chirbes, in Beniarbeig, Alicante. We have taken this opportunity not only to learn the role of the foundation that bears the name of the writer, but also to trample on the geography that saw the writer born and died, which so often appears in his books.

The last message is June 2013. That spring Rafael Chirbes pulled out a horrible On the shore, I proposed an interview, but to see if we left it for after the summer: “I’m terribly dry, I don’t know how many conversations later.” Back in 2008, after taking out a terrible Crematorium, I regretted having done that first remote interview, rather than taking the car and heading to Beniarbeig. I don't know what happened next in the fall of 2013, I don't remember it, but the next news I had from Chirbes was that of August 2015. His death surprised us in Galicia, probably in the sweetest holiday period of all time. It was pointless to insist later on: I had definitely missed the opportunity to interview Chirbes at home.

Being a Catalan speaker, but not writing in Catalan, produced a contradiction, as noted in the article 'Places and languages'.

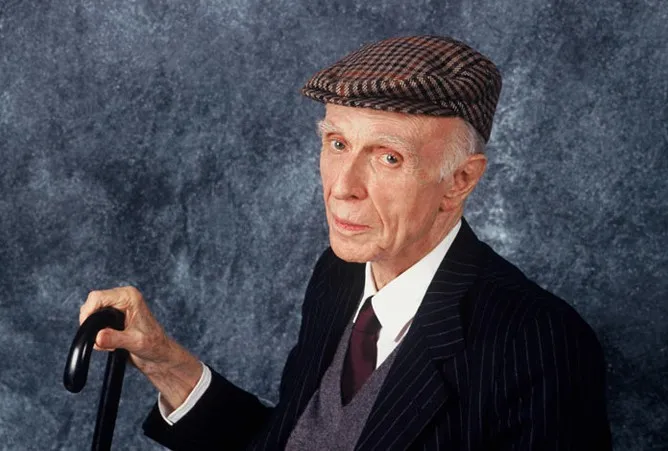

I did not want, however, to visit the house of Chirbes. Moreover, when I learned that his family, his nephews, a nephew, Manolo, had created a foundation dedicated to his uncle and offered the possibility of visiting the house of Beniarbeig. My uncle's wish was that for almost twenty years, the last ones, visitors should be opened to the house in which he lived, and the books and texts that were there should be presented for consultation and research. The Library, of some 6,000 copies (including Bernardo Atxaga, Kirmen Uribe, Harkaitz Cano), is now in the process of cataloging. Perhaps more important: you can read unpublished manuscripts, including novels. Unpublished novels, which the writer wrote in his youth and never wanted to publish in his life. Although I have had the opportunity, which the family will not publish either, “who we are now to frustrate my uncle’s will”. Another thing is the writer's memoirs, the six places he left on the street.

Another of the works carried out by the Foundation is precisely the dissemination and dissemination of the work of the writer. The novel La buena letra, translated into Valencian Catalan, will be published at the end of this year in ETB-2. Chirbes, Catalan, always cared about the mother tongue, which, having been educated in Spanish and in Castile (when her father died, in the schools of orphans of railway workers), never lost. Its status as a Catalan language, but not as a Catalan language, as indicated in the article Of Places and Languages: “I felt the pain of having lost that language to my writing again.” The protagonists of the novel La buena letra will thus have the opportunity to speak in the language they spoke for themselves in the near future: “We found it strange,” says Manolo, “not being able to read in his mother tongue a writer who has returned to German, English, French, and even Chinese.”

In the short narrative The year that snowed in Valencia, recently published with the house Anagram, there is also the clash between languages, as the writer understood it, as a class conflict: the people of the capital do it in Spanish, those who come from the villages in Valencian, the bottons and the subjects are exposed. Always within fiction, but in this story you can guess the signs of the writer's biography: the father just died, the family joins in a birthday party with a little farewell. Not in vain, the child narrator, instead of going to the real Ávila de Chirbes, will go to the fictional Coruña: “I was already beginning to know that we were nowhere.” I presume that, having previously shown accession to the place of origin: “I wanted to be part of all this.” The Chirbes Foundation organized an international conference in 2018 to celebrate the 30th anniversary of the publication of its first novel, Mimoun.

Marina Alta

However, the intention of the trip to Beniarbeig was not only to know the house of the Chirbes, who have been witnesses. Not only with much mime, meet a nephew who bears the name of the writer, Manolo. There has also been a desire to know the geography that the writer was breathing to see, smell, touch his lost paradise, his recovered paradise. It has already been said, forced to move here and there since the eight years, Ávila, León, from one school of orphans to another, to study universities in Madrid, teachers in Morocco, Barcelona, A Coruña now, lived for twelve long years in a small town in Extremadura. Without forgetting, in his work for the gastronomic magazine Mesa toured every corner of the world (some of the articles he included in his book The Sedentary Traveller). And yet, “I have had the impression that all the trips have served me to better read the place of origin.” In literature, he went back and forth to his places, to his geography, to his small country: “I’ve returned – The Good Letter, The Hunter’s Shots, The Long March – almost involuntarily to the distant stories of the past of my life that occurred here in Valencia.” Until its physical lap, around the year 2000.

"I have had the impression that all the trips have served me to better read the place of origin," Chirbes wrote.

Beniarbeig, Marina Alta, Alicante. Tavernes de la Valljusto, 40 minutes from the native country he calls Bovra in fiction, appears as Misent in the Dénia of his parents, in the Crematoria or in On the terrible shore. Behind Monte Segaria, opposite the large Mediterranean (“flea paquidermo”), the beach of Marineta Casiana, so close to the house of the grandparents, that somehow closes the vital circle of Chirbes, where its ashes spread. In Dénian himself, on the verge of death, the family met and the last meal was celebrated. Or he had spent the last few years from his detached house to the urban area, not slow to reach the taverns, through the oranges. In the literature, it had a maximum: you have to tell what's out there, even if it upsets someone, what you see. And what Rafael Chirbes saw from his home is this. He who had caught him in the books. Landscape after the outbreak of the real estate bubble. Abandoned vegetable gardens. Zarzal. Waste covered with grass by fall rains. The land remained on the verge of urban grading.

You are right: the idea was not just to know the house. Not only with much mime, meet Manolo, who bears the name of the writer. I didn't even know the geography that the writer was breathing. I would say that my intention was to make a visit to which I was unable to make a living.

Ereserkiek, kanta-modalitate zehatz, eder eta arriskutsu horiek, komunitate bati zuzentzea izan ohi dute helburu. “Ene aberri eta sasoiko lagunok”, hasten da Sarrionandiaren poema ezaguna. Ereserki bat da, jakina: horra nori zuzentzen zaion tonu solemnean, handitxo... [+]

Adolfo Bioy Casares (1914-1999) idazle argentinarrak 1940an idatzitako La invención de Morel (Morelen asmakizuna) eleberria mugarritzat jotzen da gaztelaniaz idatzitako literatura fantastikoaren esparruan. Nobela motza bezain sakona da, aparta bere bakantasunean, batez... [+]

Ekain honetan hamar urte bete ditu Pasazaite argitaletxeak. Nazioarteko literatura euskarara ekartzen espezializatu den proiektuak urteurren hori baliatu du ateak itxiko dituela iragartzeko.

Aste honetan aurkeztu da Joseph Brodskyk idatzitako Ur marka. Veneziari buruzko saiakera. Rikardo Arregi Diaz de Herediak itzuli eta Katakrak argitaletxeak publikatu du poeta errusiar atzerriratuari euskarara itzuli zaion lehen liburua.

"There were women, there they were, I met them, but their families locked them in the mental hospital, put them in electroshock. In the 1950s, if you were a man, you could be a rebel, but if you were a woman, your family would lock you in. There were some cases, and I met them... [+]

Gauza garrantzitsua gertatu da astelehen honetan literatura euskaraz irakurtzea atsegin dutenentzat: W. G. Sebalden Austerlitz argitaratu du Igela argitaletxeak. Idoia Santamariak egindako itzulpenari esker, idazle alemaniarraren obrarik ezagunena nobedadeen artean aurkituko du... [+]