"We are descendants of a world that has passed through the sink of history."

- We have met in Hernani with the Barcelonés who live in Valcarlos, in the space of after the meeting and the desk. In the search for information about Marc Badal, it is usually found with organic farming, occupation, self-management… In fact, since 20 years ago he knew the libertarian experiences of the mountain and the countryside, he has been immersed in the practice of social transformation.

Nou Barrisekoa da baina urteak egin ditu Pirinio inguruetan, Huescan eta Nafarroan. Ingurumen zientziak ikasi zituen, eta agroekologiaren alorreko master bat egin. Artikuluak eta liburuak idatzi ditu landa-eremuko talde esperientziez, nekazalgoaren historiaz eta hazien joan-etorriez. Gaur egun, Cristina Enea fundazioko Haziera hazi artxiboaz arduratzen da, eta Kanpoko Bulegoa kolektiboko kidea da.

Where does the interest in the rural environment come from?

Within the rural occupation there are very diverse people, there are people who came from the punk environment, who abandoned the crazy life of the city and went to the mountain, then other more hippies… But we were native militants of the city. I myself, my friends and those who today are colleagues, were immersed in the movement of occupation of the city and approached the rural and rural environment through political militancy.

While we were in Barcelona we had experiences of this kind, occupied villages such as Sasé (Huesca) and Arizkuren (Navarra), and some members of self-managed social centers began to make self-criticism, to see if what we were doing, selling beer in parties of okupas houses, was self-management.

“You left the barricade and went to plant lettuce.” What's that like?

In Barcelona, we were told that, literally. At first I started researching those who had gone to the mountain and then I became them. I discovered a new world in those occupied villages, and that feeling is very strong. They tend to be amazing places, other than where you live, and the projects also look amazing to you. Then, as you go deeper, you also see deficiencies, but in that 20 year effervescence you think that in a place like this you can work much more on the self-management of everyday resources, not only in the material, but in the relationships and organizational forms. Another thing is what's really there, and we could talk a lot about gender relations and power roles, but those are the miseries of practice, because in all projects, in principle, it's about transforming all of that.

Where did you go?

First I was in Sasén, which was at risk of being evacuated and finally evacuated. There we gathered a lot of people waiting for the Civil Guard, and because they didn't come, they sent us to go to meetings that they had organized in Arizkuren, and there we went. Then I returned to Barcelona to finish the career and studied the experiences of Pyrenean occupation for the final study work, especially in the counties of Garrotxa and Ripollès. I spent eight years at home, back and forth, coordinating things. Navarre, Huesca and Alta Garrotxa were my main areas.

What kind of projects were they?

Areas that are usually chosen in this regard are rather extreme, so most projects focus on self-sufficiency. In these places, you can usually do it by working outdoors, collecting money, grapes or apple, or perhaps with a small production of homemade cosmetics. If you want to produce and sell vegetables or meat ecologically, there are more suitable sites, so people who want to do so can turn to other sites.

After the initial “euphoria”, you published other kinds of reflections on the limits of the rural shake (Erratum Faith: Rural agitation against its limits).

I have been giving lectures throughout the State on these issues for many years. Then, Dani López and I, from the Madrid collective Under the asphalt is the orchard, coordinate a collective book with texts and experiences of 50 people. Dani was in Madrid and I was going and coming, the fanzines in my backpack. For many years I had to work as coordinator and dynamizer, and all of a sudden, some authors, quite read in the environment, began to talk about rural occupation as if it were the solution to all the problems of the world and in the talks there was always someone who said that: “What we have to do here, like those of Lakabe, is to leave everything and go to the mountain.” I wrote the text to respond to this trend. We have been selling and disseminating our projects for many years, and it is all very well, I am not saying that our projects are absurd, but let us not deceive ourselves or others, saying that this is the panacea and that everyone should do as we are.

The text mentions the material limits.

On a material level, the issue of self-management is quite limited, you cannot get out of the whole of the industrial production network of goods: you need gasoline, materials, tools… You can cut a lot, and it is true that in Sasén, for example, small slabs were built with clay and native stones, but that is an exception. And then, what is the self-sufficiency of food, because some chickens, the orchard, milk… Nobody plants cereals or legumes all year round. It is therefore clear that this needs to be rethought.

In any case, in his view, immaterial borders are the key.

Personally and in coexistence, our projects fail there. It's not just about us, everybody in general fails, conflicts are in any workplace and in any family. We are no better than others, but no worse. It is true that one of the main objectives of our projects is to establish a new framework of relations, coexistence, personal growth ... Each one will know with what intention it has gone to a certain place, but I would say that it is not, as such, about having an orchard; the orchard is a means, you want to help you eat what you have sown, to build with other people, etc. However, since there are many people who have known and left that community, I know people who have spent many years in Arizkuren or Lakabe and who are willing to go on there. So…

You haven't returned to the city and now you live in Valcarlos.

Those of us who have been in these kinds of communities, and despite leaving them, we wanted to stay on the mountain, 90 percent of us have targeted smaller groups. It's been clear for some time that I didn't want to live in large groups. I've lived with four other friends, with two other friends, and for five years we've been in Valcarlos.

What has changed since the first few years?

Relationship with local people. Looking back, I would say that this has changed considerably, we at that time had no relationship with the rest of the people who lived in the countryside, we lived on the sidelines and, in most cases, there was a dispute. It’s true that it’s easier to relate to two people (and they also consider you husband and wife) than to 20 people, as neighbors don’t know who lives there or who doesn’t, or if you have livelihoods. But, at least in my case, and I think it was for everyone, at that time we had no interest in the history of the people around us.

But now it's different. Slowly I also got in touch with peasant organizations, etc., outside the ghetto, and I started to read more about the history of agriculture, analyzing what has happened in that rural world we live in and, therefore, what people think that is not like us.

You are talking about the disappearance of the old rural world in the book that has just been republished: Outdoor lives, nostalgia and prejudices about the peasant world.

Many of us who have gone to the mountain accuse us of nostalgic, because they say that we want to recover a world that they have thrown out of the sewers of history, but the truth is that most of us don't know that world, although most of us are descendants of peasants in the second or third generation. The people of the old rural world never wrote their story, but others, especially men. I wanted to review and dismantle the topics that have been written about the rural world.

How has this world gone by the gorge of history?

It is a consequence of many factors and each territory has its own characteristics. But if we go back a bit, the closure of the communal lands was a tremendous failure, in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, with the creation of a modern, centralized, monetarized state by the state of the agricultural economy... The question of the management of the territory changed radically, and the plain people suffered a tremendous blow; moreover, at that time, and not by chance, industrialization and the proletarian began.

On the other hand, we must not forget the project of European colonization. This was, on the one hand, one of the main foci of the original accumulation of capital, which would later serve the Industrial Revolution, but also, for the first time in the plantations of the Caribbean, in modernity, attempted a large-scale monoculture, approached by slave workers. Sugar, above all. He tried a new logic of production. Then, the great European owners – Codorniu and Freixenet, for example – started, thanks to the money earned in the colonies and the Enlightenment, to set up farming schools and introduce new techniques into their lands. A new vision of agriculture was formed, the food industry was launched…

What about the Spanish state?

In the Spanish state, in the 20th century, something called Franco happened, and in those 40 years great atrocities were committed, but among other things, the countryside was emptied, agricultural production destroyed and the collective strength of the organizations and unions of the primary sector was dismantled.

I have not been able to prove it 100%, but I would say that the phenomenon of the abandoned peoples is entirely Spanish, and I say it Spanish because it is a consequence of Francoism: In the Pyrenees there are over 400 empty villages. Villages, yes, with church, fifteen houses and 70 great leaps. In the State there are about 1,500 villages abandoned, not to mention the dwellings, the masses and the cortijos.

Returning to the subject, after the Francoism there was a transition, and the first professional sector was already crushed, both in the organizational and the anonymous, and in 1986, when Spain wanted to enter Europe, there was the last blow of the sword: The Netherlands, Germany and France accepted entry, provided that they sold certain agricultural sectors, especially dairy cattle, which affected the Cantabrian coast.

The difference is, therefore, noticeable in the South or North of Euskal Herria…

Yes, in Valcarlos it looks clear. The case of Gipuzkoa and Bizkaia is special, because of industrialization, but the Upper Navarre, for example, was very affected by everything I have told you now about Franco, and contrasts with that of Behea or Zuberoa. In the North you see a lot of young people with the herd, thanks to the food craft law they can sell cheeses without doing so much investment, there are big fairs and, above all, the collective organisations in the North and, in general, the agricultural unions in France have a great deal of strength. In any case, there is a trend, and in Iparralde too small farms will have to close in a period of 20-30 years.

What trend is that?

It makes no sense to cook in Europe today, because it comes from Russia or Brazil or whatever. The technical imperative promised by the economic imperative says that only large-scale economies are profitable, and as it is now possible to take things away thanks to oil, small-scale family production has no future. It must be remembered, however, that there are still people living from agriculture in our environment, but the data cannot be denied. In Gipuzkoa, and this is a historical fact, only 0.8% of the working population was engaged in agriculture. It is precisely the degree of development and modernisation of countries that is measured in the same way: the less agriculture, the more modern and the more developed the country is. There are many factors, but, as has been said, fossil fuels allow us to eat as we eat today, and we know that those will be exhausted before it is too late… So, we may not see it ourselves, but the trend will necessarily change.

Kanpoko Bulegoa kolektiboan dabil buru-belarri Badal. Hanka bat Luzaiden dauka, landan, eta bestea, berriz, kultura garaikidean: hala, “hor tartean dagoen eremua jorratu nahi dugu”, eta horretarako sortu dute kolektiboa, “landako kulturari eta lurraldeari eskainitako gogoeta-eragilea”. Aurten, Arnegi eta Luzaideko ibarraren bi aldetara bizi diren jendeak bildu dira, eta horren fruitua da bilduma baten lehen alea: Endemis[t]moak: muga bizileku. Informazio gehiago, Baserriko Arte Sarearen webgunean.

Dozenaka auzokidek babesa agertu diote proiektuari igandean. Alde Zaharreko lokala udalaren jabetza da, eta hiru urte dira hainbat eragilek elkarlanean okupatu zutela.

Pasa den asteko "kaleratze ilegala" salatu dute hainbat herritarrek, ostiral arratsaldean.

Joan den asteko kaleratze "ilegala" salatzeko, manifestaziora deitu dute ostiral arratsalderako.

Ustez, lokalaren jabetza eskuratu dutenek bidali dituzte sarrailagileak sarraila aldatzera; Ertzaintzak babestuta aritu dira hori egiten. Birundak epaiketa bat irabazi du duela gutxi.

Protestak 24 ordu bete dituenean, suhiltzaileak bertaratu dira udaletxera eta kateak moztu dizkiete bi gazteei. Bi kateatuek gaua bertan igarotzea "udaletxearen hautua" izan dela adierazi du Gazte Asanbladak, eta udalaren ordezkariek "ekintza deslegitimatzeko eta bi... [+]

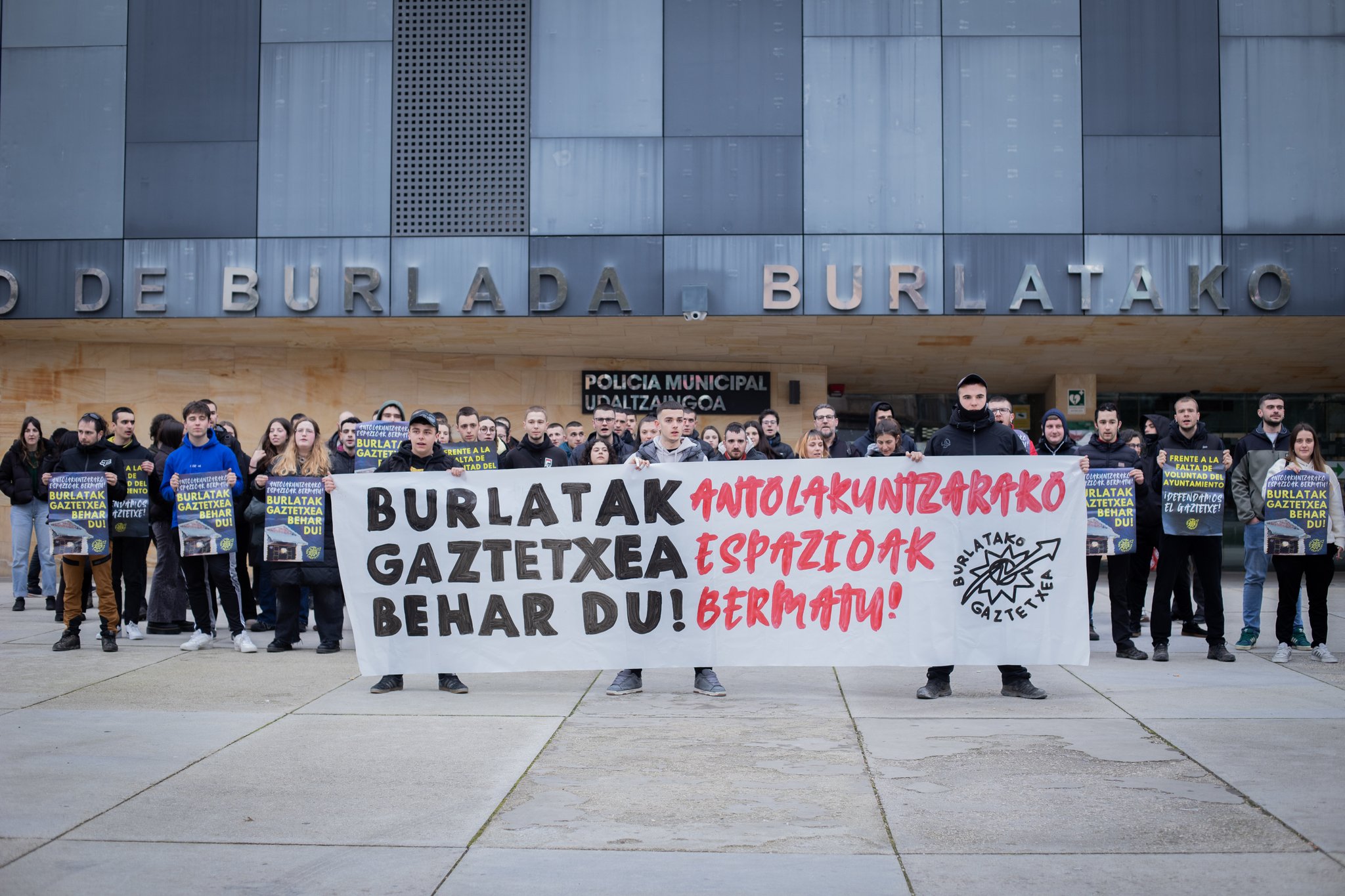

EH Bildu agintean dagoen udalak gaztetxearen etorkizuna ziurtatzeko aterabide bat adosteari "uko" egin diola salatu du Burlatako Gazte Asanbladak. Beste hainbat gaztek udaletxe kanpoan kanpatu dute, eta goizean zehar bertara hurbiltzeko dei egin dute.

Iruñerrian bat egin dute hainbat Gazte Asanbladak, Burlatako Gaztetxearen alde. Etxarriren desalojoa gelditzera deitzeko, bestalde, manifestazio bat antolatu dute Bilbon hilaren 28rako.

Asteburu honetan hasiko da Gaztetxeak Bertsotan egitasmo berria, Itsasun, eta zazpi kanporaketa izango ditu Euskal Herriko ondorengo hauetan: Hernanin, Mutrikun, Altsasun, Bilboko 7katun eta Gasteizen. Iragartzeko dago oraindik finala. Sariketa berezia izango da: 24 gaztez... [+]

Festa egiteko musika eta kontzertu eskaintza ez ezik, erakusketak, hitzaldiak, zine eta antzerki ikuskizunak eta zientoka ekintza kultural antolatu dituzte eragile ugarik Martxoaren 8aren bueltarako. Artikulu honetan, bilduma moduan, zokorrak gisa miatuko ditugu Euskal Herriko... [+]