"We crawl to one side or the other of the conflict and devour our our contradictions and weaknesses."

- Uxue Alberdi (Elgoibar, 1984) has just published the novel Jenisjoplin. It's developed over the last three decades, in the whirlwind of political conflict. The documentary includes, among other things, the experiences and shocks of two generations that have a difference of 30 years. The writer has skilfully combined two-stroke fluctuations with people's trends; the atmosphere in the bar hole and the explosive atmosphere of gaztetxes. Alberdi is a writer and bertsolari. An episode of the 2013 Bertsolaris Championship finals is important in history, although it is rarely mentioned. The novel has multiple, sharp edges. The interviewer has grabbed one of these sharp edges to start the colloquium, aware of the possibility of slipping. Bertsolari Uxue Alberdi and actress Nagore Vargas (Jenisjoplin) have become one of the most daring protagonists.

“He was not a great fan of Bertsolarism, nor did he enter the profile of the inventoried patriot...” says Nagore Vargas at the end of the novel.

I belong to a family that has the profile of “inventoried patriot”: Euskaldun, fond of Bertsolarism, mountaineering… However, in adolescence I had colleagues of origin very similar to the protagonist Jenisjoplin. At the time of the institute, which I came from the ikastola, I was accompanied by the children of Spanish origin. It is strange, by chance, that I did not become friends with those who touched me a priori, with eight Basque surnames, but of Spanish origin. I had the opportunity to get to know other realities. Some of them were Basque, rebels like Nagore [Jenisjoplin inherited the Basque from his mother Arantzazu Alkorta], others knew Basque, but they usually spoke in Spanish, some showed a strong ideology of the left of the family, but under the epithet of “models” they had misgivings about the liberation of Euskal Herria. I was going to the place of those friends, and on the wall was a Spanish flag next to the Ikurrina. The Spanish flag was for me an aberration. I began to become aware of the identity confusion that existed in our people around the age of twelve. I wanted to reflect that novel.

How has the political conflict influenced the bertsolari of your generation?

According to Garai, the relationship with the conflict has been very different according to age. It's not the same to be born in 74, 84 or 94. The events surrounding the conflict have been recorded in different ways in our heads, and according to them, bertsos are also being sung today. Those of our generation have lived the crudest moments of conflict when we were children and adolescents, we still did not have thought organized, we still have the experiences of when we were young. There was no talk “with determination” of the conflict surrounding us, and a teenager organizes the thought in a bicentric way: good and bad, nice and ugly. The messages you receive in the midst of a conflict of size seem very contradictory to you. They tell you “killing is bad,” but then you’re in the middle of the conflict and you realize that there are many factors at stake, you don’t know how to act on that.

Jenisjoplin is a portrait of the conflict in Basque society. Woven into the thread of your experience, it reflects the complexity of this society.

In the novel, identities appear mixed and sometimes clashed. It is, in a way, a testament to the marginality that I met in Elgoibar in the 1990s. That's been within me so far. For a moment, I decided to form the character of Nagore Vargas and build his environment. The conflict has lasted for several decades, and in time, nuances of nuances, most of us have slipped back and forth, we have devoured our contradictions and weaknesses, and each of us continues with our group.

How have you experienced the conflict the bertsolaris of your generation when you have sung bertsos?

Well, according to how and where we were. I did not dare to sing through the cracks, I sang without betraying my ideas, more or less in accordance with what my semejantes.Empec could agree to at 22, in 2006. To start with, I already had a lot of work riding the bertso. When you jump to the plaza first you have to understand how the bertso works in each session, you are learning the genres: bertso-afari, festival, event, bertso-poteo, championship... At the same time, you must meet the bertsolaris who work with you.

“As a writer, I still find out what I do pretty well and what I do not do well”

Then, it comes and becomes more critical of your donation. “What am I here for?” she asks. As your weak points become stronger, you sing for your contradictions. Times and themes change, and you see that your previous generation also questions some things, and you also get that path. The bertsolaris of our generation (Julio Soto, Miren Amuriza, BEÑAT Gaztelumendi...) came after a very powerful generation [Lujanbio, Iturriaga, Elortza, Maia, Irazu…]. They transformed the Bertsolarism of their predecessors, both politically and aesthetically. We have been their youngest brothers and sisters, we have acted under their protection. Now is the time to draw our environment and draw the conflict, that's what we want, but it's not making it easy for us, nor for the people younger than us. Beyond the bertsos, until about ten years ago, there has been a way of talking about politics, but how can we give voice and aesthetics to our socio-political framework? How do we put those who today are 20 and 50 years old talking together about politics? How do you do that interview? In what code? We still lack bridges for it.

It would be worthwhile to write a novel that remembers the conflict, since the Bertsolaris are the protagonists.

Yes. I have also thought that on one occasion, but it is very difficult. Because we're a very small town, because people and characters would be very identifiable, in the case of Bertsolaris. It's hard to get it right, but it's a very interesting world, which has barely gotten to fiction. It's true that if someone were to get the bertsolaris environment right into the novel, they would see an incredibly rich context.

The novel ends with a moment of the 2013 Bertsolaris Championship final at Barakaldo’s BEC. On the occasion of the clash between Maialen Lujanbio and Amets Arzallus, AMETS won. Nagore spoke to “Itzel. Rome loves heroes,” she tells her friend Irantzu. In this sense, he has affirmed that “some bertsolaris of our generation have begun to defend the culture of fragility”, “we are on the path from the culture of heroes to that of vulnerability”. Please get away with that idea.

Singing about conflict or other issues and giving them political meaning is not easy, singing from fragility is not easy, it seems that vulnerability is not rational. That is precisely the challenge now facing us, that of guessing contradictory doubts and feelings within a political framework. But how do we build the context? In other words, vulnerability, pain, anger and pain are not personal and private issues. The wounds left by the political conflict, each has its own and must be left. That passage in the book, in which the characters comment the face to face of the bertsolaris championship, I have included it in the novel because it coincided in time with the hospitalization of Nagore and the Championship. And also because the opportunities that Amets and Maialen did or the roles they took allowed me to delve into the topic I wanted to deal with.

What did those roles mean?

We've done a lot of epic in bertsos, and in the finals there's been a lot of epic. The listeners also, unintentionally, ask the bertsolaris for an epic. Amets sang at that end, among other things, from the role of a civil guard and from that of Zaitut, and, with the word "Altzoa", he addressed the whole mother and the big figures, which is very normal, surely what most of us would do and not as well as him. You're at BEC, you've got 14,000 people in front of you, and inertia leads you to epic. Maialen, for his part, escaped from these pulses and drew the anti-heroes. He referred to the time of the return, but not the return to the Basque Country, but to South America. She put herself on the skin of an immigrant woman who has been caring for the elderly. An anti-hero. Upon hearing the lap, Miguel Strogoff, conscious, escaped to his mother's skirts. Constantly fleeing from our heroes and myths. The verses were a reflection of our times, they served me a lot, I saw myself far from the great figures of Maialen. Some were clouded by Maialen's performance, the Bertsos didn't come to them. According to Nagore and Irantzu in the novel “we all want the epic to die.”

Can you win the txapela who supports the anti-epic pulse?

Of course. But the path of the edge, of the weak, of the vulnerability, of the antiheroes -- it's more difficult because it doesn't require primary emotions. These kinds of roads pull the inner layers and demand the depth of thought. When you touch the shores, when bertsolari runs unwalked roads, it is not certain that Rome will follow you.

Returning to the novel, “My aunt Karmen Vargas died of AIDS in May 1987. He was twenty years old. Seven years earlier, one morning in 1980, Rosa Moreno, my grandmother found a syringe in the house umbrella,” says Nagore. The novel starts in 2010.

The novel is developed and set in different eras and spaces, and what has cost me the most is to combine them well. There are several turning points, for example, in the case of Nagore being diagnosed with AIDS. I couldn't put that in the beginning, but I couldn't delay it too much, so I decided to take two parallel chronologies, one from 82 to 2003, and the other from 2010 to 2014. I decided to use different rhythms in both of them. I begin with the second, in those times there are many activities and the dialogues of the protagonists are more intense, the passages of the past are more narrative and descriptive. I realized that the alternation of the two eras could help each other, that understanding what happened in the past could help the reader understand the present, understand Nagore, give a new depth to their own decisions, where they came from, where they came from.

“When we talk about identity, in a small town like ours, we turn to the essence, we ask where we came from and why.”

The pair of Nagore Aranburu consists of Luka Moretti and Nagore Aranburu, respectively. It gives an appropriate touch to history, its character is the right one to express the conflict.

Above all, because it's very quiet. As I wrote, I read an article called The Sociability of the South. The text highlights five features of the sociability of society in the South. Luka had those things, but when I read them, I further completed their nature: courtesy, tranquillity, play, not drama, another way of living time. Nagore is more from Iparralde, needs immediate results, understanding things and rationalizing them… Luka flexibly looks at problems, knows how to say things across, then leaves them… Nagore has to understand why Luka is with him, but Luka doesn’t have to reflect on it. Luka is from Euskal Herria and from the world, it has no roots here, its identity is not essential, but built. When we talk about identity, in a village as small as ours, we turn to the essence, namely where we come from and why. For Luka only serves for what, love is not why, but for what. The same was true of the clashes. What for? Why not?

We've seen Nagore in the hospitals. You have reflected well on the hospital environment and learned well about AIDS.

Yes. I have to thank Felix Zubia [She works in the Intensive Care Unit of Donostia Hospital. It's bertsolari, because it has helped me in the medical aspects of the novel. If I got into a topic like that, I couldn't brush it up and it's over. If I wanted to write accurately, I had to learn. Felix taught me the San Sebastian Infection Unit. They did it in the 1980s, and room bars are still being kept, so there's talk of a lot of suicide attempts. Currently, 90% of the users attending this unit are patients diagnosed with AIDS. Every two days a case of AIDS is diagnosed. I've read many of the books that came out in the '90s. The letters of the relatives of the sick and the speeches of the doctors and parents of the deceased were also detoxified. One of those books is At the foot of the horse, by Justo Arriola. Arriola is from Elgoibar, the Karmen Vargas generation. I have read it carefully, I wanted to write from my point of view of generation, without too much influence, because otherwise the novel would not be counted from the perspective of the protagonist, Nagore Vargas.

The book is alive, largely built through dialogue.

Yes, writers do it from our capabilities. I had the story in mind, I knew what I wanted to tell, and I've done a lot of tests before. Some have served me and some have not. I once told the editor, “I’ve begun to describe this passage along, and I’ve realized I’m not Saizarbitoria.” I mean, I don't know how to build a six-page text about a woman going to bathe on the beach, a text that works, of course. At least yet. [Lili and I talk about novel]. For me, these scenes have a great literary value. Saizarbitoria knows how to do it, each knows what its powers and its limits are... I still discover what makes me pretty good and didn't guess what.

You are bertsolari and writer. How do you feel treated as a writer? Because it is said that bertsolaris are better “treated” than writers. Or not?

I'm doing two things, because I like both. Fortunately, I am sorry to have the attention of a group of readers. Jenisjoplin has been a three-year job, I've given everything I've ever been able to, the process has been very intense and expensive, but very nice. I've slept a little a year, I've been worried that I get a bill later, because I've written without ceasing to sing bertsos in the plaza, and also the custody of two children. I have narrowed a lot in that regard.

On the treatment with the writers you say, I think there are very different cases. The attention each writer receives is different, and the sensations of each writer will also be different, in relation to that attention. And the truth is, probably, the ratio between the writer's work and the attention he gets is not always fair. But not in the case of the bertsolaris. I understand that many writers say they don't get the attention they deserve, but I also know so many other bertsolaris who feel the same. Today, we are not so many of the bertsolaris that we often walk from place to place. For example, there are championships that have a very high level and that have no place in the plaza. “Life is neither logical nor just nor coherent: learning to live with it,” the challenge psychologist once told me. I try.

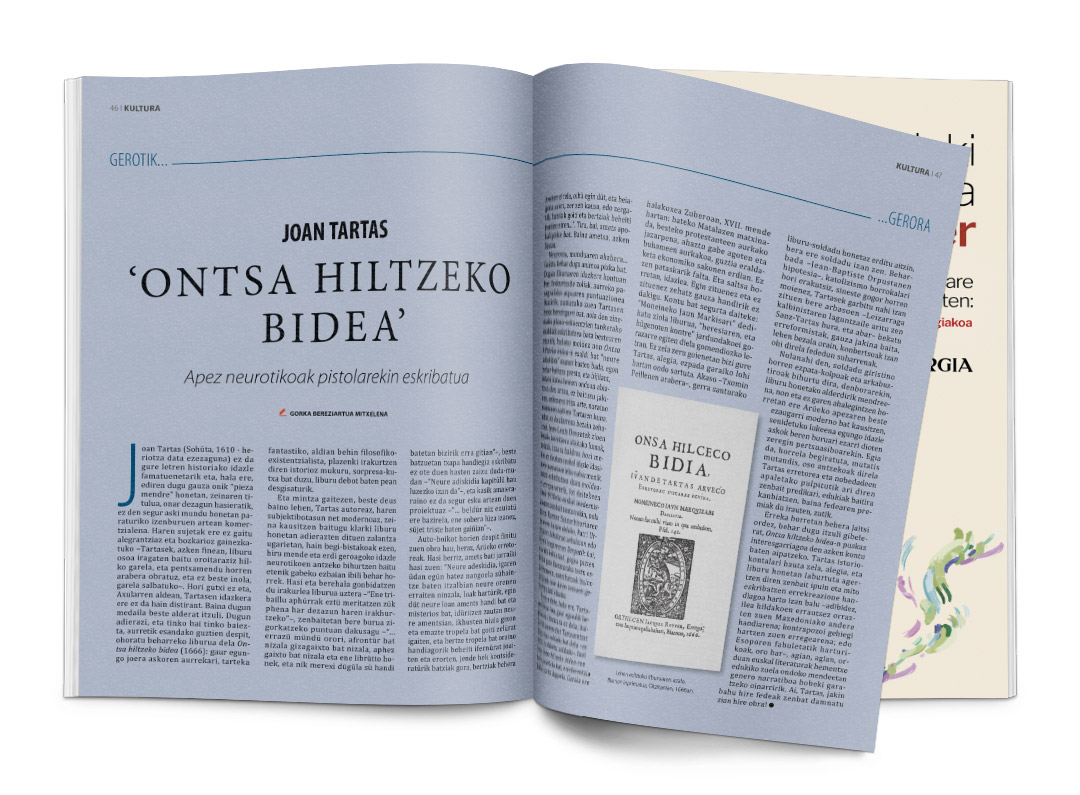

Joan Tartas (Sohüta, 1610 - date of unknown death) is not one of the most famous writers in the history of our letters and yet we discover good things in this “mendre piece” whose title, let us admit it from the beginning, is probably not the most commercial of the titles... [+]

ilbeltza-(1).jpg)

.jpeg)