Guaranteeing new, increasingly weaker drugs

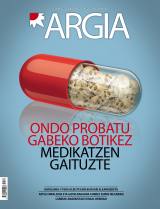

- There is no completely safe medicine, so the company that wants to bring a new medicine to the market must demonstrate that the benefit it brings is greater than the harm it can cause; however, in recent decades the criteria used to ensure it have been “reassured”. A proposal by European regulators to shorten the procedure for admitting medicinal products is now on the table, and many voices in the health sector have expressed concern about the risk that this may entail.

The body that grants or refuses marketing authorisations for medicinal products in the European Union is the European Medicines Agency EMA. In the United States, it's the FDA that does that work, and in most countries around the world, it also respects what those two say. But the system hasn't always worked that way. Until the mid-1960s, medicines could be marketed with very few tests. The Thalidomide scandal changed the situation.

Thalidomide is a drug that was sold between 1957 and 1963 and given to pregnant women to relieve nausea. At first it was a success in Europe, which was not marketed in EE.UU, because the FDA refused authorization, but left serious consequences: thousands of children were born with severe malformations because of it. In response to the tragedy, the Western agencies conditioned the authorization of medicines to the conduct of clinical trials that we know today.

Juan Erviti, Worker of the Department of Health of Navarra:

“There has been deregulation since the 1980s; regulatory agencies increasingly require pharmaceutical companies to be able

to market a medicine”

“The conditions for granting authorizations became increasingly strict – in the strictest sense of the word – until the early 1980s,” explains Juan Erviti, head of the Medicines Evaluation Service of the Department of Health of Navarra, “but since then there has been a deregulation that is required of pharmaceutical companies less and less to be able to market a medicine.”

According to Erviti, one of the main milestones in the deregulation process was the establishment in 1990 of the International Harmonization Council (ICH). ICH is composed of the regulatory agencies of the United States, the European Union and Japan, as well as representatives of the pharmaceutical industry of those countries.

“That draws attention,” says Erviti, “it’s like participating in the exam design that a student will have to overcome later.” The ICH takes important decisions on the regulation of medicinal products which are subsequently incorporated into national legislation.

From better to not worse ... or yes

In the past, the creators of a medicinal product had to demonstrate that the compound they intended to market was more effective than those already used for the same disease. “But from a moment,” Erviti tells us, “it was decided that it was enough not to be worse.” In addition, the interpretation of “not being worse” is too flexible, according to the Navarro pharmacist: “Although the new drug is slightly worse, it is considered the same, as it is taken for granted that this small loss of quality is not clinically important. But the way to measure the difference is very subjective and debatable.”

On other occasions, the comparison of the new drug in clinical trials with placebo alone is supported and the efficacy of the molecule in tests with respect to the reference compounds available on the market is not analysed.

This generous practice often causes drugs that are inferior to their history to go out into the market and also take away space because pharmaceutical companies promote new drugs. In fact, the oldest alternatives on the market, when the patent is exhausted, can often be sold in a generic way and do not represent a major benefit for companies.

In the best cases, few improvements that come from the hand of the new drugs are significant, as most of the new molecules that make up the private laboratories are usually variants of the existing ones, which only bring small benefits for patients (see attached table).

Flexibilizing in the face of insecurities

The safety criteria for new medicines have also been reduced, according to Juan Erviti: “Today, some drugs that have shown symptoms of safety problems in clinical trials are accepted to be marketed.” In this case, the commercialization of the new molecule is conditioned to the elaboration of the so-called Risk Management Plan, which foresees, among other actions, the carrying out of phase IV research. This means observing the effects of the medicine on patients after its marketing.

It should be noted that, even in the largest clinical session, there are far fewer people who test the medication than those who are actually going to do it. A harmful effect may occur in one out of 5,000 or 10,000 receptors; in the trial phase it is difficult for the medicine to be given to a large number of people, so it is advisable to observe the effects of the new substances even after they are placed on the market. That is precisely one of the tasks of the service run by Juan Erviti.

“Unfortunately, these phase IV investigations set out in the Risk Management Plan are not carried out in most cases,” he criticizes, “they ask for extensions, delays occur… Once in the market, it is very difficult to ask the producer to do such tests.”

As an example, he recalled a medicine for COPD (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) authorised in 2014, called Anoro. During clinical tests, it was found that its use may increase the risk of heart or brain problems. EMA gave the green light to marketing, but conditioning the producer – the GSK company – in carrying out a Phase IV study for risk measurement.

“The problem is,” Erviti complains, “that the deadline for presenting the study results is 2024, ten years after the authorization, for which the company will surely no longer have any interest in this product”.

Accelerating does not improve quality

Until a few years ago, there was a single type of authorization of drugs, which was overtaken by phase III clinical trials. But regulatory agencies have opened up other avenues for marketing some drugs that admit the scientific evidence to be weaker.

One of these is the authorisations granted under “exceptional conditions”. Juan Erviti explains that they are mainly administered to “orphans”, that is, to those who are going to be used as a treatment for some rare diseases. “Because the number of patients is very low, it is good that previous research will be of poorer quality and that both efficacy and safety data will not be as good as desired.”

“Conditional Permission” is another type of license on the same line that has been opened in recent years. “At one point, the EMA and the FDA decided to speed up the release of certain drugs into the market,” says Erviti, “especially against life-threatening or highly vulnerable diseases.” Accelerating means that overcoming phase II testing, so testing in few people is sufficient to be able to market the new medicine.

“That has its good side and is successful in society because, in theory, it is beneficial for patients to have new alternatives at hand as soon as possible, as regulatory agencies are arguing, but in practice it is being seen that, in general, the measure has not had benefits,” says Erviti. According to an article published in the journal of the European Society of Oncology, the significant reduction in the time allowed for the marketing of medicinal products has not been a significant therapeutic advantage for patients.

Other recent research has similar effects. According to an article published in early October by the European journal British Medical Journal (BMJ), 57% of cancer medicines approved by the EMA in Europe between 2009 and 2013 (a total of 39) had not been shown to increase survival or improve the quality of life of patients at the time of their marketing. Six years later, only six of the 39 had shown that they had some improvement. Very similar numbers, something worse actually, were found in 2015 by a similar study done in the United States. It should be borne in mind that new cancer treatments have an average annual cost of EUR 75,000.

With the new authorisation figure that they want to implement in the European Union, the door will open much more to the marketing of medicines tested with very few people.

Other researchers have concluded that in many cases where new medicines are an improvement, this improvement is virtually nil. For example, the lengthening of patient survival for a couple of months on average, always with regard to cancer treatments, to which it should be added that these small benefits have been frequently observed in trials with patient groups not in accordance with reality: they are usually younger than most patients and have few health problems together with the disease being studied.

It is precisely another major flaw in the current system of authorisation for medicinal products that people who choose clinical trials laboratories are very different from those who are then actually taken: “They reject the elderly, also those who have more than one pathology… They are fictional samples. Therefore, in practice, it is observed that many medicines give many more problems than expected after they have been marketed”. The Professor of Pharmacology at the Autonomous University of Barcelona, Joan Ramón Lapor, gives the following example: “In 70% of clinical trials for the treatment of infarction, the participation of people over 70 years of age is not allowed, but 70% of those who died from infarction are in this age group.”

Final step: adaptation pathways

At the moment, the European agency EMA is trying to add a new step on the road to deregulation, as many health professionals and groups have denounced. Adaptative pathways is called in English, we could translate “paths of adaptation” into Basque. Juan Erviti uses the “adaptation permit”. According to him, the entry into force of the pathways would mean extending the possibility of granting conditional approval to any type of medicinal product, provided that “there are unmet clinical needs”.

Accordingly, the new medicinal products may be marketed simply by overcoming phase II of the tests, leaving for the future the presentation of the evidence usually obtained in stages III and IV.

Europe is studying ways of adapting through a pilot test. EMA has made a positive assessment of these tests, so it is possible that a new authorisation figure will soon be incorporated into the regulations, despite the concern of many professionals. This will satisfy the old wishes of the pharmaceutical industry, which consider the current authorisation system too long. Companies in the sector and patient associations, among others, argue that the current model of regulation is not sustainable and demand a paradigm shift that allows to put in the hands of patients the new drugs that can save lives as soon as possible.

An article published in August by the British Medical Journal says that NEWDIGS think tank, funded by industry, is responsible for the new regulatory model that the EMA has adopted. The article, signed by a work team led by biologist and physician Peter Gotzsche, strongly criticizes the intention of the EMA, remembering that half of the new compounds that successfully exceed phase II fail in phase III.

An attack on public health?

“[EMAk] also assumes that once these drugs are placed on the market, solid clinical trials can be carried out quickly,” can be read in the BMJ article. However, the authors do not agree: “In the European Union, evaluations of medicines published under conditional authorisation were completed on average four years after marketing, with a significant delay of half.” As a main conclusion, the signatories claim that they are under the pressure of the EMA industry by accelerating the authorisation procedures and that the application of the adaptation permits may pose a risk to the marketing of medicinal products without knowing their benefit and damage balance.

Spanish journalist specializing in health issues Miguel Jara has signed the article entitled “The new European system of authorisation of medicines, a risk to public health”. “I very much agree with this statement,” says Juan Erviti. He has reminded us that iatrogenesis, i.e., death from medication intake, is already one of the leading causes of death in the West: “There is an English expression: the elephant in the room. And this is a great elephant; with drugs, we heal, but we also kill a lot, and nobody wants to see it. We've sacralized medicine and we don't want to hear it's imperfect."

“Araudia biguntzen hasteaz gain, 80ko hamarkadan beste aldaketa garrantzitsu bat eman zen: marketin sailek hartu zuten laborategi farmazeutikoen kontrola, sail zientifikoen ordez”, dio Juan Ervitik. Horren ondorioa izango litzateke farmaindustriari maiz leporatzen zaion jokabide bat: inbertsio handiena sustapenean egin eta gutxi arriskatzea benetako aurrerapausoak ekarriko lituzketen baina garatzeko zail eta garestiak diren sendagaiak ekoizten.

Hala, egile ugarik azpimarratu dutenez, konpainia farmazeutikoek kaleratzen dituzten medikamentu berri gehienak dagoeneko existitzen diren beste batzuen aldaera soilak dira, terapeutikoki oso hobekuntza txikia dakartenak, edo, ikusi dugunez, batzuetan ezta hori ere. Ingelesezko me too (ni ere bai) esaldia erabiltzen da halakoak izendatzeko.

“Horrela jokatuz, nahiko erraz sortzen dituzte produktu berriak, hogei urterako patente baten babespean”, azaldu du Ervitik; “salmenta prezio altua ezartzea lortuz gero, diru asko irabazten dute. Nafarroako Osasun Saileko langilearen esanetan, merkatura ateratzen denaren %85 mota horretako produktuak dira. “Gainerako %15 oso sendagai onak izaten dira, baina jendeak ez dakiena da horien bi heren inguru AEBetako sistema publikoak garatzen dituela, ez laborategi pribatuek”.

AEBetan funts publiko asko eskaintzen zaio sendagaien garapenari, eta legeak baimentzen du molekula garatu duen funtzionarioak patentea enpresa pribatu bati saltzea, gobernuak sosik jaso gabe. “Sistema horren bidez, farmazeutikek merke antzean erosi eta oso garesti saltzen dute”; dio Juan Ervitik, “AEBetako unibertsitate eta zentro publikoetan zertan dabiltzan behatzen ari dira etengabe”.

Beste ondorio bat sendagai gehiegi egotea da. “Espainian 10.000 medikamentu finantzatzen du sistema publikoak”, dio Joan-Ramon Laportek farmakologoak, “baina 400 inguru besterik ez dira behar. Nor da gai 10.000 gauza ondo ezagutzeko?”.

Saiakuntza edo proba-saio klinikoa sendagai baten garapenaren azken urratsa da. Laborategian lortu den molekula berria gizakiekin probatzean datza, eta lau fasetan banatuta dago:

I fasea: pertsona osasuntsu gutxi batzuei ematen zaie substantzia berria. Molekulak giza gorputzean zer nolako portaera duen behatzen da, baita toxikotasun zantzurik ba ote dagoen ere.

II fasea: I fasea gaindituz gero, tratatu nahi den gaixotasuna duten pertsonei –200 ingururi, gehienez– ematen zaie konposatua, medikamentua zein dositan eraginkorra den neurtzeko, gehiegizko dosia zein den ezartzeko... Beste talde bati une horretan merkatuan dagoen botika ematen zaio, edo plazeboa, molekula berriarekin konparazioa egiteko.

III fasea: ehunka edo milaka pertsonarekin egiten da, behin dosia ezarrita. Sendagaiaren benetako eraginkortasuna ezagutzea da helburua, baita ordura arte atzeman ez den efektu kaltegarririk dagoen behatzea ere. Lehen derrigorrezkoa zen fase hau gainditzea medikamentu berri bat baimentzeko; gaur egun, kasu batzuetan, aski da II fasea gainditzea, eta aukera hori zabaldu nahi dute europar agintariek.

IV fasea: sendagaia merkaturatu eta gero hartzaileengan dituen efektuak aztertzean datza. Oso portzentaje txikian ematen diren bigarren mailako efektuak atzemateko balio du, baita ere botikaren eraginkortasuna epe luzean neurtzeko.

Sendagaien kontsumoa handitzen ari da –bai gizakiona, bai abereena– eta horrek sendagaien hondakin bolumena handitzea dakar. Sendagaien hondakinek ingurumenean duten inpaktua aztertu nahi izan du Saioa Domingoren doktore-tesiak.

For a while, girls and boys from families in social difficulties, wanting to participate as little as possible in the oppressive socio-economic system, try to settle in the world of manufacturing: they cultivated their creative capacities in the production of jewelry or... [+]

The Ekin Emakumeak association operates in Arrasate. “Our three axes are Euskera, diversity and women,” said Amagoia Muniozguren Urkiza. During the months of February and March, a workshop of herbs for women to work on self-management of health has been held.