"We wanted a tall, believing man, not a monster."

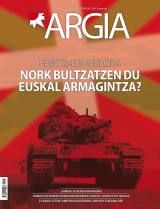

- The relationship and experiences of Migel Joakin Eleizegi, the Giant of Altzo, and his brother Martin, spin "Handia", selected to compete in the Official Section of the San Sebastian Film Festival. We've played with reality and myth, story, character psychology, technical challenges -- with movie directors.

On the one hand, myth and legend, on the other hand, reality. Time, distance, personal memory -- they transform reality.

Aitor Arrangi: When we started documenting about the Altzo Giant, we saw the same thing. There are historical data, not many, and many legends and small stories (lees that drank 20 liters of cider, another tells you that he raised a bull from the branches…). What is reality and what is myth, it's a matter that's very closely linked to this character, because the stories about it are also being transformed and deformed.

Jon Garaño: Just like other characters create myth around Altzo's giant, the movie does the same thing, we're part of that game.

My brother's vision predominates.

J. Garaño: At first the protagonist was Migel Joakin, but then we realized it was more interesting to see the giant through the eyes of another, both to tell the story of the giant and to talk about everything that was around the giant, of society at the time. For us, in the film this context of the nineteenth century is fundamental: there are two forces in the conflict, the old world and the new world, through the Carlist wars, and before that one of the brothers takes a position. You don't want to change, but you're doomed to change it; the other wants to change it, but it's limited.

You say that the movie is part of that game between legend and reality. What benefits and risks does it have on the basis of real history? How far have you left yourself when it comes to betraying reality?

A. Arrangi: When it's based on reality, people give another dimension to history, although it's just one more narrative element, because you're never going to tell it exactly, because you have to synthesize it, because there are black holes -- in this case there's little documentation and black holes were going to be filled. In addition, you have to give fiction a logic that often doesn't have reality. The material is real, but you have to take it to your ground, you have to be flexible and know how to make your story, because if you feel like you're a slave to the data, you can put aside the story; and at the same time you have to set limits to be honest with the story and with the character. This exercise has been carried out continuously.

J. Garaño: There's a lot of real data in the movie, a lot of important data that we know about the giant, and anyone who's read about it will find it in the movie. We have also taken care of some details: you see the reproduction of a Madrid newspaper of the time, the illustration they made of Handia… Let people find out what is true and what is invented.

“Like other characters create a myth around the Giant of Altzo, the film does the same, we are part of that game.”

You have made your story. I've read to you that if we don't tell our story, others will tell it.

A. Arrangi: Not only the story of an era, we also hope that it is a story that contributes to our cinema, that it dialogues with other films, as a complement, but not with the ambition of being a unique story.

J. Garaño: It's clear that we put our perspective on history, and it's also clear where the roots are.

“Not only the story of an era, but also a story that contributes to our cinema, with the ambition to be a complement and not a single story”

And from your point of view, in some circumstances the film does a political reading of the time.

J. Garaño: I would say that the characters in the film have no political conscience, but social consciousness. They realize that something is changing, that there are different worlds, and what interests us is how they deal with those changes. Some are able to adapt to the situation according to their interests and others have no intention of adapting, they want to maintain what they always have. In the Basque Country, for example, there has been a tendency to tradition and to want to keep things as they are.

A. Arrangi: The identity element has a great weight in the film.

.jpg)

The story revolves around two protagonists full of nuances, a psychological film based on the story of two brothers. The work of the actors is fundamental in these cases.

J. Garaño: It has been a very tough film for everyone, because the technical conditions have not been so easy, and the actors have also done a great job. Although the film is a very broad portrait, the truth is that it is basically a psychological film and it is important to count beyond what is said, for which the work of the actors is essential. We are very pleased with the outcome of all the actors, and in the case of the protagonists, Eneko Sagardoy [the Giant of Altzo] is a camaleonic actor, very physical and with a great technique, who has achieved something very difficult: Make the giant Miguel Joaquín credible, bearing in mind that the character has a great dramatic evolution. Joseba Usabiaga [Brother Martin] transmits a lot with her eyes through little gestures and gives authenticity to the character, draws the struggle between what he is and what he wants to be; getting the characters to see themselves and the spectators otherwise, that's a big challenge. And the chemistry among them is very important, because the film reflects that, despite being very different characters, they have moments of connection, that something brings them together.

You like symbols and metaphors. Is the wolf of Handia the sheep of Loreak?

J. Garaño: There's a lot of symbolism, yes, but those things don't count, that every viewer does their own interpretations. There are a lot of details, we like to put them to the viewer, although not everyone will watch them. They are also assiduous to us, assiduous ones that indicate that the film wants to tell something, about society, about identity, about freedom, about change, about adaptation… We try not to be cryptic, but not too evident.

A. Arrangi: The giant itself is a metaphor for us: the physical evolution itself in the film somehow reflects the myth that grows and transforms, that cannot stand and grows, because the only thing that is unchangeable is change.

Have you been asked for a long time to decide what features the Basque people are talking about?

J. Garaño: It's given us some headaches, because it's not the most realistic treatment, but in the end we've decided not to put the characters to speak just Gipuzkoan, because to begin with, we don't know how it was actually talked at that time. Characters donostiarras, navarros, coasters… they also speak different languages. And we've made some gestures to the current Basque of Altzo. After all, it is certainly not the most realistic Basque, but we have preferred naturalness, and on that road we have had the help of many.

“The chemistry between the two main actors is very important because the film reflects that despite being very different characters, they have moments of connection, something unites them”

To roll you have crossed almost the entire Basque Country. What is the importance of landscape in the movie?

J. Garaño: The landscape and the earth are of great importance, as they mark the story and the characters: where they are, what route they make and where they end. The landscape unites us to the universe of the characters, because the environment also makes the person.

A. Arrangi: Playing with the landscape also allows you to combine the epic with the intimate space.

In 80 days you mentioned the qualitative leap from the film to Loreak (in aesthetics, in assembly…). This time you've had the challenge of taking a leap further and representing a giant. Do you like taking risks?

J. Garaño: This has been a challenge to see that the team is able to make such a production, as technically it is a great production for us. In addition, LOREAK brought us many joys and nice things, but in the end we ended up tired and we were clear that this film had to be something else, different. Realizations, the way we bring history -- they have another style, although then we've realized that there are more connections between the two films than we believed; we recognize the things of our universe, more than we believed.

A. Arrangi: We have had many challenges: To create the 19th century convincingly, to work with animals, to imagine war -- and the giant himself. We've combined analogue tricks and digital effects, and every plane and scene has been an analysis and a fight, because what was worth on a shooting day might not work on the next one. We've always been clear that we wanted a tall, realistic, convincing man, natural, not a monster, for the viewer to come into history and not always thinking about the techniques behind getting the giant. The giant protagonist, who will develop emotions, who will be in contact with the other characters and who at the same time will not cover the story, has not been easy to balance.

You seem to end the tired flowers of the film, but the comparison is going to be inevitable. Do you fear or trust the antecedent?

J. Garaño: There will be comparisons, yes, and the new film will have another reception and a tour, but we are calm, because we have made a different film and we have not wanted to make Loreak 2.

A. Arrangi: Because of the influence of Loreak and the attractiveness of the character of Altzoko Handia, we have noticed that there is a lot of expectation, yes. It's a little scary, yes…

.jpg)

“We have realized that ours is not a personal seal, but a team seal: we are able to recognize Moriarti in our films”

It is understood within the philosophy that you have in the production company Moriarti, but someone will say: Together with Garaño he worked as director of LOREAK to replace Jose Mari Goenaga, and now there is Aitor Arrangi.

A. Arrangi: In our case, it's normal and it's not a big change, because we've been based on teamwork and we've been handing out and changing roles in short, documentaries and fictions that we've done right from the start. Jose Mari is where I was in Loreak. If it has logic in the way we work, let no one think that Jon and Jose Mari have become angry, haha.

J. Garaño: Aitor and Jose Mari are very different and therefore the dynamic has also been different, but we have not had to adapt, as in Moriarti we have worked together from the beginning. Over time we have realized that ours is not a personal seal, but a team seal: we are able to recognize Moriarti in our films, we repeat the issues that interest us and the ways to treat it. By performing different films, we find connections and connections between them.

A. Arrangi: In our work you will find paradoxical characters, communication problems, identity…

You are accustomed to the red carpet and, in part, as representatives of the Basque film industry, you said that you feel responsible. Is it a burden or a pride?

A. Arrangi: No weight, no pride. We're not the only ones, our contribution is one that can attract spotlights at any given time, but fortunately there are a lot of people doing interesting work, and if we're opening doors to those who can come from behind and show that in Euskal Herria there's a chance to make movies, it's a joy.

J. Garaño: Nobody has appointed us as a representative, but it is true that our films have travelled abroad and that it is a good opportunity to make known the reality, the culture, the language here. Despite the fact that ours is a small industry, it is increasingly larger and diverse, and I think that in the Basque film they come years long, there are interesting projects on the way.

Watch trailer:

James Francoren Urrezko Maskorra, Anahí Berneriren eta Sofía Galaren zilarrezkoak eta Handiak jaso duen Epaimahaiaren Sari berezia dira aurtengo palmares ofizialeko puntu nabarmenenak.

Jendeak barre egin nahi du, eta negar; sentitu, emozionatu. Beharbada horregatik irabazi du tragikomedia batek Publikoaren Saria.

James Franco zuzendariaren The disaster artist filmak irabazi du Donostiako Zinemaldiko film onenaren Urrezko Maskorra. Jon Garaño eta Aitor Arregiren Handia filmak Epaimahaiaren Sari Berezia eskuratu du.

Bai, zaharrek ere desio sexuala dute, eta bizitzaz gozatu nahi dute, maitasunaz. Eskubidea dute erokeriaren bat egiteko, euren kabuz erabakitzeko, aske izateko… eta gustuko ditugu hori guztia gogorarazten diguten filmak.

Dena iritsi behar da, goizago ala beranduago, amaierara: maitasuna, gerra, filmak eta aurtengo Sail Ofiziala. Der hauptmann alemaniarrarekin itxi da lehiaketa ostiral goizean, erretirada prestatzen hasi da prentsa, baina larunbatean palmaresa ezagutu arte, apustuak egiteko... [+]

Sail Ofizialaren azkenaurreko egunean izen bat nagusitu da: James Franco. Zuzendu eta protagonizatu duen The disaster artist filmak publikoaren algarak eragin ditu.

Dibortziatu eta bakoitza bere aldetik zoriontsu izan nahi dute, baina euren bizitzak berregin ahal izateko zama bat kendu behar dute gainetik: semea. Posible al da ama batek, aita batek, haien semea ez maitatzea? Galdera batzuek erantzun konplexua dute.

Kotxean zoaz, autobidetik. Aurretik doan ibilgailua zure arrebarena dela ohartu zara. Aurreratzea erabaki duzu, klaxona jo eta agurtzeko.

The Goonies eta Indiana Jones. Nire umeetako film kuttunenak zeintzuk diren galdetuz gero, horiek nire bi erantzunak.

Normaltasuna fikzio eskuraezina da, baina ustezko normaltasun hori lortu nahian gabiltza denok. Happy End filmean, goi-mailako familia burges protagonista ere normala da… itxuraz.

Garrantzitsuena ez omen da nondik zatozen, nora zoazen baizik, baina Zinemaldiko Sail Ofizialaren seigarren egunean ikusi ditugun filmetako protagonisten kasuan, jatorriak erabat baldintzatzen du beraien istorioek izango duten bilakaera.

Dokumental dibertigarri, ero, sinestezin eta surrealista honen protagonista absolutua, karisma harrigarria duen Julita dugu.

Ogia eta atzamarra labana berarekin mozten direla dio esaera zaharrak eta Zinemaldiaren Sail Ofizialean hori gertatu da: egun berean etorri dira film onentsuenetakoa eta errefusaren ontzian botatzekoa.

Sutsua, gerrillaria, pasionala da 120 battements par minute, Act Up taldearen aktibismoa bezalatsu.