Basque Country forest to forest

- With the arrival of the solar station, it is common to see our people from the coast fill up with local people and from outside. The beaches are often revolted, massively, almost without space for placing the towel. It seems that in the good time we forget not only the maritime destinations, but also the possibilities of exit to other natural spaces, such as forests.

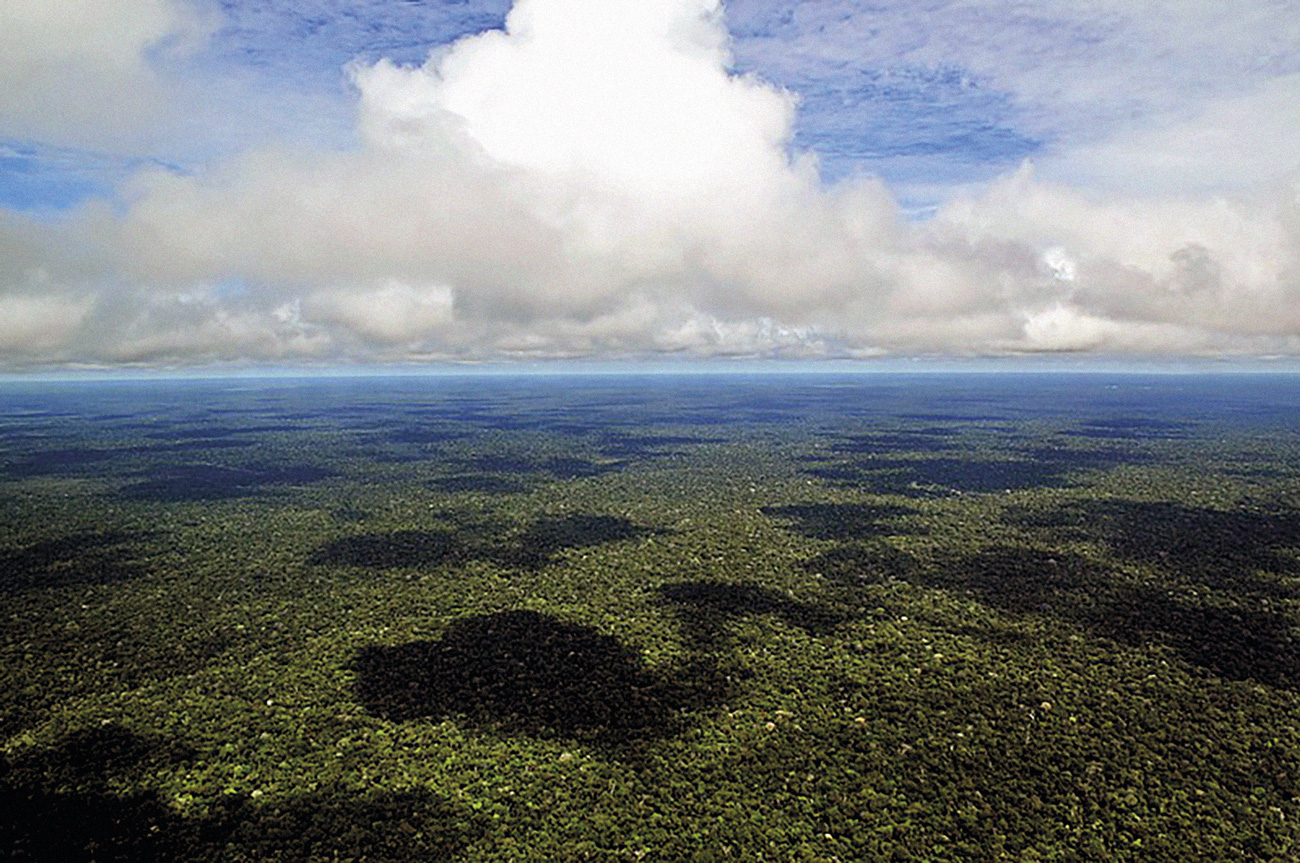

We have eleven forests in the Basque Country, each with its forms, characteristics and characteristics. Some of them are located within the Natural Parks, in protected areas. Many others are not part of any known park or natural space: the visitor will be surprised by the amazement at the charms of these little-known forests.

What does the forest offer us? What is the charm of the forest? Some will bring it together to calm, to freshness in the shade, to loss between animals, plants and trees. It will approach the area in search of other forests: fruits, mushrooms, medicinal herbs… The forest is generous. Whatever the reason it is lost, we cannot deny that we all become a little more “savage”, that sense makes us sharper and gives us time to feel part of nature.

In this report we propose a trip: We will cross Euskal Herria from one side to the other, moving forest to forest and making stops in some of them. We have drawn the route following the border marks between countries, from west to east. So, come on!

Starting point: The Izki Forest, a Maternity Paradise

We will start the tour of the Izki Natural Park. It is a forest nestled in the Alavesa Mountain, within the municipalities of Bernedo, Arraia Maeztu and Campezo. Among all plant and tree species, the Izki forest has a main protagonist: Ametza (Quercus pyrenaica). Approximately half of the 9,000 hectares of forest are occupied by the marojals.

“In Izki there is an important correlation between geology and vegetation: the center of the forest, the valley through which the Izki River passes, is a very sandy environment formed by Ameztias. The peripheral areas are more rocky areas and are made up of bladders and bladders,” explains Jonathan Rubines, a Natural Parks technician in Álava.

On the other hand, despite the fact that they occupy a very small area, Izki is characterised by the muddy areas that go to the earth’s surface, the small, packaged waters. These wells, known by their inhabitants as “zapaka”, are very rich spaces of flora and fauna, since they contain many species that do not exist anywhere else.

In the vegetation, the technician stands out a type of narcissus that grows inside the forest: the common lilipa (Narcissus pseudonarcissus). It's one of the first to flourish in spring. In the March-April area, in the interior of the still brown forest are formed the pastures of narcissus of yellow color, giving a special touch to the landscape.

When entering the forest, it is advisable to keep your eyes and ears, both from the ground and from the air, as many animals can be found in Izki. If the mother reigns among the trees, the woodpecker has that role among the animals. The park has six species of woodpeckers, which occurs in very few areas of the Iberian peninsula. In addition, Izki is home to about 30% of the peninsular population of the median peak (Dendrocopos medius), the main species of the park. “This is a very important environment for the conservation of this species,” explains Rubinés.

Izki Park receives around 50,000 visitors a year, but Rubines is clear that Araba Park has the chance to receive more people.

Gorbeiatik Aizkorri-Aratz: on the land of the beech

To the north-west of the Izki Natural Park we find Gorbeia, on the border line between Álava and Bizkaia. Declared Natural Park in 1994, it has an area of 20,016 hectares and a large number of forests of oak, beech, pine and other species. The beech forests predominate in the Álava area: The most significant example is Altube's vast hayedo.

East of Gorbeia, we left Bizkaia behind and followed the Gipuzkoa-Álava boundary until reaching the new destination: Aizkorri-Aratz Natural Park. The director of the Aizkorri-Aratz Natural Park, Valentin Mugarza Martinez, explained that about 10,000 of the 19,400 hectares it has are forests: “On the one hand there are natural forests created naturally, such as hayedos, robledales and meljares, and on the other the planted forests, formed mainly by different types of pines and allergies.” The beech trees dominate the surroundings of Aizkorri-Aratz, as of the approximately 7,000 hectares occupied by the natural forests, 6,000 are hayeds. Towards Álava, however, marshes and jigs, which occupy about 1,000 hectares, also play a leading role. “The beech is spreading, and that has a bad face: the site is being devoured into the oak. One of the objectives of the park is to keep and take the oak trees to the surface,” the director tells us.

In fact, pedunculated oak (Quercus robur), a typical tree species in the Basque Country, was lost a lot in Gipuzkoa and Bizkaia due to the logging and the availability of land in private hands. In Aizkorri-Aratz, today, the robledales, both hot and not hot, make up about 400 hectares. By the unreed oak (Quercus petrea), there are about 200 hectares in the park. “It is one of the largest forests of this species in the CAPV.

The exploitation of these forests for the production of coal means that the current forests of the park environment are mainly young forests between 60 and 70 years old. “This directly affects the fauna: old trees, dead wood, etc. are necessary for the richness of the fauna.” However, the Natural Park of Aizkorri-Aratz, despite not possessing the same wealth as in the old forests, hosts many species of animals: in addition to birds of prey and others such as the alimoche, the red milano, the black peak, the triton of the summits, the Iberian frog, the snow terrain and many other animals.

Road to the Lordship of Bertiz, crossing hayedos and robledales

From Aizkorri-Aratz to Navarra, we cannot fail to mention the natural parks of Urbasa Andía and Aralar. In the border line of Álava, Navarre the first and in that of Gipuzkoa-Navarre the second, beech forests predominate.

Following north the border line between Navarra and Gipuzkoa, we will cross the third natural park of the stage: Peñas de Aia. Significant are the forests of robledales and hayeds surrounding the Añarbe reservoir, places of great diversity of animal species. In addition to the surface richness, the underground space should be highlighted: The visitor approaching Aiako Harria will have the opportunity to immerse himself in the mines of Arditurri.

By Aiako Harria we entered Navarre and headed for Ipar Euskal Herria, we finally reached the third and final goal of the tour: Natural Park of the Manor of Bertiz. When I spoke to him about the idea of the report on the forests of Euskal Herria, Miel Mari Elosegi, a biologist and forestry technician from Navarra, he immediately referred to Bertiz. “Trees are born, ripe, die and rot, that’s the entire natural cycle of a forest. And that looks great in Artikutza and Bertiz,” he explained.

It is surprising that Bertiz, a forest so close to the nuclei of Oieregi and Oronoz-Mugairi, has suffered so little human intervention. How is that possible? Well, to find the answer, you have to explore a little bit the curious history of the Bertiz forest. In 1898, Mr. Pedro Ziga Mayo and Mr. Dorotea Fernández bought the Lordship of Bertiz, and on his death they gave the estate in a will to the Provincial Council of Navarra of the time. The only condition he was required to maintain the forest, without interference, without any change.

Hayedos and robledales live in the 2,040 hectares of Bertiz Park. Less, but there are also smoothies, meljars and brezals. And of course, the stately environment, especially for jungle birds, is the right place for many species of animals because of their forest richness.

"Dead trees are rotting, and that looks like a mess. Many say, ‘This is forsaken!’ But no, the point is that forests are like this,” says Elosegi. What Bertiz is is not regular and controlled. The biologist compares the forest with any society, there must be trees of all ages: old, young, newborns…

After the return of the rich Bertiz forest, here we end our forest tour. We could go ahead and pick up the border line of Navarre–Iparralde, and cross the famous Irati forest, and then continue towards the Pyrenees, and… As we have said before, there are many forests that we have in Euskal Herria, and all the impossible can be included in a single report. In any case, we hope that in summer we have turned on the worm to lose ourselves in the forest, always with our heads: let us leave the car at home, take care and respect the environment and avoid the massification of the beaches in the forest. It ended if not ...

Zertan da basoa udan? Zein fase bizi du urtaro oparo honetan? Jakoba Errekondok eta Miel Mari Elosegik bat egin dute azalpenean: udan lanean ari da basoa, hosto guztiak aterata eguzki energia aprobetxatzen, fotosintesia egiten, bere gorputza fabrikatu eta zabaltzen, udazkeneko uztarako eta negua pasatzeko prestatzen. “Udan dena dago bor-bor: landareak, animaliak, perretxikoak… Guztia!”, dio Errekondok. “Basoaren iraupenerako fase garrantzitsuena da uda”.

Gizakion biziraupenerako ere ezinbestekoak dira basoak, beharrezko dugun oxigenoa sortzeaz gain igortzen dugun karbono dioxidoa xurgatzen baitute. Zuhaitz motaren eta bestelako ezaugarrien arabera aldakorra izanik ere, U.S. Forest Service and International Society of Arboricultur erakundearen arabera, zuhaitz hektarea batek 19 pertsonarentzako adina oxigeno sortzen du urtean. Horrek esan nahi luke, adibidez, Arabako biztanleen erdia Izkiko basoak sortzen duen oxigenoari esker bizi dela. Ez da makala!

Iratiko Basoko Lizardoia eta Isabako Aztaparreta pagadiek jaso dute UNESCOren izendapena. Uztailaren 7an, Europako jatorrizko zenbait pagadiri aitortu zien “salbuespenezko balio unibertsala” nazioarteko erakundeak, eta horien artean daude Nafarroako biak.

“Duela urte mordoa hainbat babes neurri jarri eta basoen sailkapena egin zuen Nafarroako Gobernuak. Zenbait basori ‘Erreserba integral’ izendapena eman zien orduan. Babes osoko gune horietan ezin da ezer egin, ezin dira ukitu, eta baso lanik ez da egin ehun urtetan”. Lizardoiako eta Aztaparretako basoez ari zen Miel Mari Elosegi, UNESCOren izendapena ezagutu baino lehen. Izendapena jaso duten bi horiez gain, Ukerdiko Erreserba Integrala da babes osoko hirugarren gunea Nafarroan, Larrako mendigunean.

“Oso ikusgarriak dira pagadi horiek, basoak berez nola funtzionatzen duen ikusteko aukera ona ematen dute, baina eremu oso txikia hartzen dute: Lizardoiak adibidez, 200 hektarea ditu, irlatxo baten modukoa da”, zioen Elosegik. Babes osoko irla txiki horiek handitzen hasteko balioko ote du aitortzak?

Naturaz gozatzeko aukera ez ezik, iraganera bidaiatzeko eta gure historia ezagutzeko aukera ere eskaintzen digu basoak. Urteetan, hamarkadetan eta mendeetan, gizakiak harreman estua izan du bere inguruko oihanarekin. Basorako gure irteerak, beraz, bestelako kultur eskaintza eta jarduerekin osa ditzakegu. Hona hemen horietako batzuk:

Antzinako aztarnategiak: Historiaurreko aztarnategi ugari daude Euskal Herriko mendi eta baso inguruetan, antzinako gizakiaren lekuko. Trikuharriak, tumuluak, harrespilak eta zutarriak dira horietako batzuk, baita kobazuloak ere. Horietako asko topa daitezke erreportajean aipatutako Aizkorri-Aratz inguruetan, besteak beste.

Meategiak: XIX. mendearen bigarren erdian garrantzi handia hartu zuten meategiek Euskal Herrian. Horien aztarna dira egun gure lurraldean sakabanatuta dauden meatze zaharrak: Aizpeakoak Zerainen (Aizkorri-Aratz) edota Arditurrikoak Oiartzunen (Aiako Harria), beste askoren artean.

Interpretazio zentroak: Erreportajean aipatutako parke guztiek dituzte interpretazio zentroak. Bisitariari harrera egiteaz gain, parkeko eta bertako basoetako informazioa emanen diote bertan: fauna eta flora, geologia, historia, antolatutako jarduerak...

Museoak: Basoen eta Parke Naturalen inguruan hainbat gairi buruzko museoak bisita ditzakegu, tokian tokiko errealitateari erantzuten diotenak. Esaterako, Egurraren Museoa Zegaman edo Gatz Museoa Leintz-Gatzagan.

The dust has lifted the actions of a group of strangers against a Kutxabank monoculture in the Urola valley. In this regard, ENBE, ENBA and GBE (Gipuzkoako Basozale Elkartea) offered a press conference. They condemned the fact and called for the perpetrators to punish it.

After... [+]