"Those here also have to approach those we've come from outside."

- Sometimes things come like this. On Friday you have an appointment with Tarana Karim, in Tolosa, as there is the Azeri activist Astindu, and a few days earlier, when you are preparing the questions, when Mursego opens two songs together with the people of Oion and advances the album he has created to foster coexistence. In the course of the interview, one cannot remove from the lips the melody that seems to be put about the situation: “I’m not you / and you’re not me / but we’re the two together.”

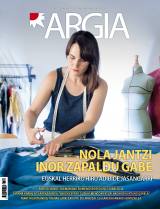

Ikasketaz abokatua da Tarana Karim; ostalaritzan eta itzulpengintzan jardun da besteak beste, eta gaur egun aktibismoan ari da buru-belarri. Bizitzak hala ekarri duelako, orain 15 urte Euskal Herrira etorri zenetik hainbat elkartetan ibili da boluntario, hala nola Caritasen eta Gurutze Gorrian. Orain dela hiru urte Ana Yurd izeneko emakume-elkartea sortu zuen, munduko emakumeak biltzeko, eta Tolosako Emakumeen Etxearen Aldeko Taldean ere badabil. Bi urte egin ditu SOS Arrazakerian lanean, eta, hori baino lehen, lau urtez aritu zen elkarbizitza bultzatzeko Bizilagunak proiektuan dinamizatzaile. Aisialdian, ipuinak kontatzen ditu: hura aditzeko aukera, Hernani Hitzetan jaialdian.

First of all, I should like to ask you to come forward.

I am Tarana Karim, Azerbaijani, born and raised there. I have lived 15 years in Euskal Herria, studying, raising my children… For my life or for my different origin, it has touched me to fight on a daily basis and break stereotypes, so several years ago I became a fighter, especially as a stranger and as a woman.

Did you study law in your hometown, do you have any relationship to your martial passion?

I would say that my eagerness to fight comes from my day to day, from the need. If you study right or not, that's what makes, of course, you know what your rights are, but as a person, at a given moment you realize that things can't be that way, that you have to change and that there's another way to do things.

Why did he come to live here?

I was younger and I found some work obstacles in my society. While I was there, I met my partner, who was from here. I arrived in San Sebastian, and I followed around.

What obstacles did you find in your hometown?

Azerbaijan, as a town, is very nice: nature, rich culture… To do tourism, it is beautiful. For the people there, there are more and more obstacles; today it is a dictatorship: you do not have freedom, the internet is controlled, the media is closed, people who want to do things are imprisoned… In my time, when entering work and university, there was a lot of corruption, and that has also worsened. If you don't have money, you can't go to college or in dreams; officially it's public, free, but everything works through money. For the people there, life is very difficult.

How did it stop here?

I arrived without knowing the language, and it was a big hurdle for me. I've been very lucky when it comes to working, there was always someone who was working in English, and I started working right away. During the first four years of my arrival -- work and home -- those were my sites, but then, after I was born children, I didn't work so much outside, and it gave me time to think about a lot of things. When you go to the park, to the library or to the store, you realize how society welcomes you. A lot of people expect us to be like the ones here, that we will act like the ones here: that's a process, and if you want to do that process, maybe you need your whole life to do it. In any case, I’m clear that I don’t want that: I don’t want to become anyone, I want how I live my life.

How did you start positioning yourself in society here?

You get a kind of filter: before, Euskera was a filter for me. In places where its inhabitants usually gather, it stays outside. I started thinking about how I could get into those places, because I live in this society, but it seems like I'm not. When I grew up a little bit, I began to participate in the projects organized by the City Council of Tolosa, to give my opinion… I am a member of society and I want to be in my place and take my opinion into account.

You learned Basque, you passed the filter and then…

I got to the places where the Basques come together, and at first they looked at me in awe, but then they've seen that I'm going to a lot of things, and they've gotten used to it. I'm in many projects, I try to participate and take the view of my collective. The municipalities say that they are in favour of equality, yes, but the possibilities given to locals may not serve foreigners, because we have other needs. Women who come from outside do not have that much network and in many situations we have other needs: that must be taken into account when making policies. On the other hand, when municipalities or associations organize things, they do not take into account that people who come from another society have another rhythm: they organize projects for everyone and say that foreigners do not go. Well, maybe those of us who come from outside don't do things like this: come and see them, ask, know ...

After the attacks that have taken place in several European cities in recent times, have you noticed differences?

The matter is going to get worse. We have come out of Muslims saying that the people who have committed these attacks are not Muslims, but terrorists, and I believe that that is why things have been clarified at least in some aspects of society, but on social networks, for example, they give us firewood to right and sinister. In addition, to the women we fight, we have topics about Muslims and machismo: we don't have to accept them, but I don't want to give explanations to those people. If you want to understand what I do, I will gladly explain it to you. But I want to get closer, as I try to get closer to Basque customs. The effort has to be bilateral, those here too have to be of interest.

Any nasty situation you remember?

For example, once I went to the Ertzaintza, because robbers entered my house, and the Ertzaina asked me if I had rented that house in which I lived, and if I received subsidies, because in that case I had to declare that it was for rent… I told him that I had my obligations to the treasury fulfilled; and besides, the work of the Ertzaintza is not that: I went to denounce, because I did not because I did not. But because I'm wearing a scarf and I have a different surname… If Etxeberria or Aranburu were to leave, they wouldn't tell him anything about it. However, these kinds of experiences, and not only my own, but those of others, give you tools to know what to do when they happen. You learn from these kinds of situations and you know where you have to set the limits.

Is it useful to share this kind of experience with others?

Yes, in addition, other women often tell that at the time they did not know what to do, and then we leave together or study ways to respond. Some people think that outsiders can be told anything, and not.

The issue of Income Guarantee has also been the subject of controversy in the Basque Country.

To collect this subsidy or anything else you have to meet certain requirements: if you meet those requirements you have the right to receive them, and it is, no matter where you are. The other thing is that there are conditions that keep the locals out, because the aid is organised in a certain way: that is not the fault of what comes from outside. The government should be required to change its conditions or otherwise call for aid.

Since you came here, you have done a lot of work, right?

Like many outsiders, I started from the bottom. I started in hospitality and started in activism and volunteering in 2003, a year after my arrival, in most of the places where there were people from outside. The hospitality work is 15 hours a day, in which it runs the whole life, but when I had time, I worked voluntarily. Then I was teaching, in English and Russian language schools, and then the Basque Government launched a project to help children from outside, for four months in school: to do translations, to be with them in exams, to go with them to the doctor… That is what I did in different locations of Gipuzkoa, including Irun, Andoain and Zizurkil.

He now works at SOS Racism. How did you start doing it?

I did slow year and peak work, but in the time when I've worked less, I've activated women's association and activism. I started to spend two years ago at SOS Racism, and there work and activism go hand in hand, it's not like making pastries, this kind of work you have 24 hours in your head and in your life.

What lines of work do you develop within this partnership?

We are working to raise awareness in order to deal with any discrimination, but above all with racism and xenophobia. We work in all areas: in society, in institutions, in schools… I manage the following projects: The Bizilagunak project, which consists of meals between families or groups inside and outside; an exhibition on refugees, especially in schools; and another project that we have been running since spring: “Muslim woman against Islamophobia.”

What does it consist of?

We offer training workshops for Muslim women to make them see what Islamophobia is, because some didn't know it: they told us that this and that had happened to them, but they didn't know it was Islamophobia. We have had very good results: in May we finished the workshops, and women, to put it another way, have woken up, have started to make contributions, want to participate… That is necessary. From what I had realized in my day, they are now warning themselves: “I have a place in society and I must participate in whatever I can.” We will not all participate in society in the same way, of course, but everyone will contribute whatever they can and will take whatever is appropriate. I think it is a process of welcoming and delivering society.

How does Islamophobia combine with gender oppression?

Islamophobia is against Muslims, yes, but when you're a woman, it's worse, you're considered weak. Sometimes they tell women what they can't tell men. In addition, they tell us that Muslim men oppress us. Once, when I was in a workshop on Islamophobia and feminism, a woman from there said to me: “They force you to wear your scarf, to see when they release you!” Imagine a woman who was in a feminist workshop! Answer: “Listen, every morning I wear this scarf, I don’t have anyone at home who sends me the scarf.” Many times, with the scarf, I'm freer than many of the women here. The freedom that you have inside your head, that's what happens; how you see the world, if you own your life… That's freedom, and don't take your scarf or not take it.

“Gure testua, Korana, gizonek interpretatu dute, eta begiratzen baduzu nola bizitzen den islama Iranen, Turkian edo Indonesian, ez dute berdin egiten: liburu bakar batetik baldin badator dena, zergatik da hain diferentea? Interpretazioak direlako. Adibidez, feminismo islamikoan dabiltzan emakumeak, arabiera ondo ezagutzen dutenak, Koran originala ari dira ikertzen, genero-perspektibarekin, luparekin. Nik ez dakit arabieraz, baina hizkuntza horretan hitz batek hainbat esanahi izan ditzake: gizonek, gehien interesatzen zaizkien esanahiak hartu dituzte, eta horri beste ikuspuntu batetik ere begiratu behar zaio”.

“Iaz, Ramadan bitartean, iftar bat antolatu genuen kalean, meskitarekin batera. Jateko momentua da iftar: egunean zehar ez dugu jaten eta edaten, eta gaua heltzean egiten dugu. Plazan egin genuen eta alkatea ere gonbidatu genuen, jendeak ikus zezan zer den, beldurra baitaukate beti ea zer egiten ote dugun meskitan, ea magia egiten dugun edo zer [barreak]. Kalean egin genuen dena: errezatu, jan, hitz egin, zalantzak argitu… Beldurrak uxatu nahi genituen, batzuk nahiko urduri daude eta”.

Gizakiok berezkoa dugu parte garela sentitzeko beharra. Parte izateko modu hori jasotako hezkuntza, ingurua... formateatzen joaten da.

Identitateak ezinegon asko sortzen du gizakiongan. Batzuetan, banaketak ere eragiten ditu, ezin dugulako jasan beste baten identitatearen... [+]

International Migrants Day is celebrated on 18 December. Last year, an institutional event was held at the Alhóndiga in Bilbao in cooperation with the social partners and I was invited to participate. There I had an unbeatable opportunity to meet new creators and, above all, to... [+]

Dorleta Mikeok esango digu elkarrekin baina nahastu gabe bizi garela, ez dagoela bizikidetzarik bertakoen eta beste jatorri batzuetatik etorritako familien artean. Mikeo eta Lola Boluda Donostiako Egia auzoan, Aitor ikastolako jolastokian, abiaburua izan zuen egitasmoa garatzen... [+]

The current Basque society is culturally very diverse, people from different backgrounds live in the municipalities, and our centers have noticed this cultural diversity, as in recent courses the enrolment of foreign students has increased considerably. According to the latest... [+]

Rosario Palomino Liman (Peru) jaio zen eta 30 urtetik gora daramatza Bartzelonan bizitzen. Katalanez erraz egiten du, eta hala ere, katalan hiztunek gaztelaniaz egiten diote, kanpotar itxura duelako. Badaki errespetuaren izenean egiten diotela gaztelaniaz, baina bera... [+]

But the rain has come at the end: How to hold Euskal Herria so green, if not,” they say. And he really has it. But in our mother's country, the earth acquires a dark tile color when it rains, as if it wasn't very clear what it's made of: tiles by land or tiles. Green meadows are... [+]

Serious situation? To whom is the extremely serious situation addressed? Who cares? If the 2018 studies, studies and surveys show that the Basque lives behind his culture, who cares?

My friend told me what it's hard to get together, at dawn, when we were in Azpeitia Square... [+]