As many plastics as animals at sea

- The issue of plastic waste that pollutes our oceans is taking a lot of pages in the media lately. The UN itself has announced that it will take action on single-use microplastics and plastics by 2020. What damage do we do with this waste?

On May 14, 1901, the whale appeared on the coast of Orio. That is what the series of bertsos that we know each other in Euskal Herria says. Something similar happened this February on the Norwegian island of Sotra. There also appeared the whale on the coast, but the cetacean, sick, came to the dying shore. Scientists found 30 plastic bags in their stomach. The case of whale can be seen as an example of what is happening, or is being done, in marine ecosystems.

In the ten minutes you will need to read this report, ten full garbage trucks will be discharged into the oceans

“For every minute we throw away the amount of waste that a garbage truck has.” With this phrase, economist Ibon Galarraga started his speech at the EkoFish Conference held last March at the Aquarium of Donostia. What does that data mean? Well, in the ten minutes you need to read this report, ten garbage trucks are discharged into very oceans. Approximately 120 tonnes of waste. There's something.

Plastic islands

In recent years, garbage accumulations in the oceans known as “plastic islands” have been known. Marine currents work like our sinks. The so-called “ocean revolutions” are gigantic mill-shaped currents reaching thousands of kilometers in diameter. Plastics and waste distributed in the sea tend to concentrate in the middle of the mill. This is how the five “plastic islands” that currently exist in the Pacific, the Atlantic and the Indian Ocean have been born. The largest, the North Pacific, has an area of 1.4 million square kilometres, more than double that of the rest of the Iberian Peninsula.

According to several studies, and as explained by the AZTI researcher Javier Franco in the EkoFish Days, there is currently more plastic at sea than plankton. “2050. By the year 2000, it is estimated that there will be more plastics in the sea than fish, depending on the weight.” But where do we get so much garbage into our seas? What are the main sources of this waste?

About 80 per cent of marine waste originates from land-based activities: industrialized environments and densely populated areas are the main springs, and most plastics have access from land to the sea by streams, in particular 80 per cent of land-based plastics reach the oceans in this way.

In the Pacific, the Atlantic and India there are five “plastic islands”; the largest, the North Pacific, is more than twice the Iberian Peninsula.

On the other hand, fishing is the most waste generated by maritime activities. Mention should be made, for example, of the influence of “ghost fishing” on marine ecosystems: abandoned nets or inactive fishing materials continue to trap and damage marine animals and organisms for long years, all the time it needs to degrade plastics.

Killer of marine ecosystems

When talking about the damage that plastic waste causes to marine living things, it is important to make a classification according to the size of plastics. “Large waste affects larger organisms such as whales or fish. Smaller residues, such as nanoparticles, microparticles, affect lower level biological structures,” said Javier Franco.

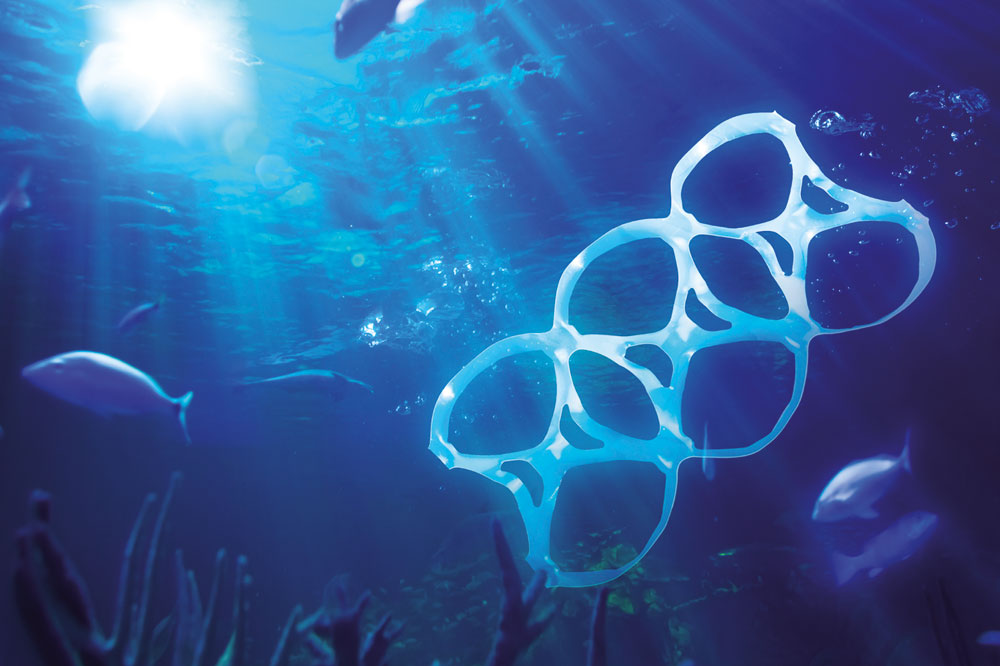

In his speech, Javier Franco focused on macroplastics: fishing nets, plastic bags, six cans plastics, bottles and plastic packaging… How does all this affect marine fauna and flora?

On the one hand, many organisms get entangled or hanged with plastic pieces. In the case of seabirds, for example, of some 400 species, 103 are affected (25%), while among marine mammals they are about 42%. Knots affect these animals in many ways: they trap the mouth and prevent feeding, reduce freedom of movement, cause amputations of the body parts or cause infections, for example. Many animals die as a result of these problems.

Another consequence is suffocation and drowning. Due mainly to plastics accumulating at the bottom of the sea, several organisms are unable to perform their main physiological functions properly. For example, the growth of many plant species and communities has been reduced in areas with many residues, as they do not allow sunlight to pass. Residues prevent the proper photosynthesis of plant species and organisms from mangroves, phanerogams and marshes. In some coral cases, scientists estimate that up to 85 percent have been lost because of these problems.

.jpg)

(Ed. : Chris Jordan

Another common problem is the intake of plastic. 40% of seabirds are affected by this problem, which affects half of the mammalian species. Animals often mix plastics with their prey, where the colour of plastics influences a lot, and in other cases, such as that of filtering animals, they are swallowed involuntarily. The same is true of secondary swallowing, that is, when one animal eats another with plastics in the stomach.

Plastic confetti on the high seas

We already know that the long time it takes to degrade is a characteristic feature of plastics. This is one of the biggest problems of plastic waste today. As you can see from the graph attached, once in the sea, plastics can spend years, decades, or even centuries floating to disintegrate. And what happens during that long time that plastic is in the water? It gradually divides.

“As a result of mechanical fractures and processes of photodegradation and biodegradation, marine plastics are becoming fragmented, to the extent that many of them are transformed into microplastics or nanoplastics.” Amaia Orbea is a researcher at the UPV/EHU and a member of the PLASTOX project. The influence of micro (less than five millimetres) and nano (between 1 and 100 nanometers) plastics on marine ecosystems is being analysed, among other things.

The special feature of plastics, and the main problem with their management, is the long time they need to degrade. Once in the sea, you can spend decades or centuries floating to disintegrate.

There are currently some 200,000 particles of microplastics in the sea per square kilometre, according to Ekologistak Martxan in the Marine, Plastic and Microplastic Waste report. These small pieces of plastic usually have very sharp vertices and often cause injury to the animals that devour them. As if it were not enough, given that plastic that has been in the sea for years contains many microbes, in addition to the physical wound, microplastics are the source of many pathogens for fish, birds and many other animals.

The main risk is that due to their size they can be ingested by basic organisms in the trophic chain. These small organisms inherit microplastics from their descendants, causing damage to the entire trophic chain, in some cases until they end up in our plates. “This problem affects the entire ecosystem. Ecosystems are very complex systems that are in constant contact and when one part is affected the whole system suffers,” Orbea explained at the EkoFish Conference.

Nowadays, in addition to the microplastics generated by the degradation of larger plastics, plastics of this size are also generated specifically for industrial use. Many cosmetics companies, for example, use plastic microspheres for creams and scrubs. Billions of microspheres end up at sea every day through our sanitation systems.

How did we get here?

Since the 1950s, the mass production of synthetic plastics began, the production and consumption of this material has been growing exponentially. In our society today, we have total dependence on plastics, that material is everywhere. “Plastic is one of today’s major industries, moving millions and millions of euros and dollars each year,” Amaia Orbea said in her speech.

Around 300 million tonnes of plastic are generated worldwide each year and, if the growth trend continues so far, by 2050 it is expected to reach 2 billion tonnes of production. The most serious thing is that, according to calculations, half of the plastic products that are manufactured have a single use. “The issues of plastics and marine waste are yet another example of the poor management of our resources,” said Ibon Galarraga.

.jpg)

In fact, in addition to the obvious damage that plastic waste produces to the environment, the economist considers that the economic aspects are also important. “After all the oil used in plastic production and all the damage we have caused, 95% of the material’s value is lost each year. We make such misuse of plastics that we lose most of their value, as if we shed about €100 billion through the toilet hole.”

To this must be added the losses that marine plastics cause in significant economic sectors, especially in tourism and maritime leisure. The European Union (EU) spends EUR 630 million each year on the cleaning of coasts and seas, among other costs.

The best plastic, the one that is not created

What to do to minimize damage? Ekologistak Martxan, in the aforementioned report, makes a number of recommendations to start taking steps towards a circular economy of plastic: first of all, to reduce, reuse and recycle plastic (the 3 Rs: Reduce, Reuse, Recicle) would be the basic measures to move to this circular model. “We have always considered the plastic cycle as something linear: taking, producing and throwing raw materials,” Galarraga said. It's about turning it around.

But it's not enough to memorize those 3 R's. Society needs to understand the need for a circular economy and integrate in a global way the way we act, for example, in our homes and in our businesses. Although it is important to ask governments and institutions to take action, when we go shopping we will take a fabric bag, disposing of single-use packaging or buying bulk products, we will be taking the first steps to change the real situation with these small actions.

Energiaren Nazioarteko Agentziak (IEA) astelehenean argitaratutako txostenaren arabera, %2,2 igo da energia eskaria 2024an aurreko urtearekin alderatuta, besteak beste, egiturazko arrazoi hauengatik: beroari aurre egiteko argindar gehiago erabili beharra, industriaren kontsumoa... [+]

Kutsatzaile kimiko toxikoak hauteman dituzte Iratiko oihaneko liken eta goroldioetan. Ikerketan ondorioztatu dute kutsatzaile horietako batzuk inguruko hiriguneetatik iristen direla, beste batzuk nekazaritzan egiten diren erreketetatik, eta, azkenik, beste batzuk duela zenbait... [+]

Lurrak guri zuhaitzak eman, eta guk lurrari egurra. Egungo bizimoldea bideraezina dela ikusita, Suitzako Alderdi Berdearen gazte adarrak galdeketara deitu ditu herritarrak, “garapen” ekonomikoa planetaren mugen gainetik jarri ala ez erabakitzeko. Izan ere, mundu... [+]

Ur kontaminatua ur mineral eta ur natural gisa saltzen aritu dira urte luzeetan Nestlé eta Sources Alma multinazional frantsesak. Legez kanpoko filtrazioak, iturburuko ura txorrotakoarekin nahasi izana... kontsumitzaileen osagarria bigarren mailan jarri eta bere interes... [+]

Greenpeaceko kideak Dakota Acces oliobidearen aurka protesta egiteagatik auzipetu dituzte eta astelehenean aztertu du salaketa Dakotako auzitegiak. AEBko Greenpeacek gaiaren inguruan jasango duen bigarren epaiketa izango da, lehenengo kasua epaile federal batek bota zuen atzera... [+]