"I just want my uncle's bones to be returned to my family's grave."

- He is a left-wing rebel painter and militant, who cannot lead to the slavery of the political party discipline. We talked for a while and he drove us to the cemetery of Our Lady. Among the dead there was no painting, but the living memory of the dead.

Irakasle izana. Hainbat herri eta eskolatan jardun zuen lanean 1972az gero, harik eta oposizioak gainditu eta plaza irabazi zuen arte. Besteak beste, Karrantzan bertan, Lekeition, Barakaldon eta Bilboko Otxarkoagan irakatsi zuen. 80ko hamarkadaren hasieran laster jo zuen gaitzak, erretirora sasoiz eraman zuen depresioak, margotzera eraman zuenak José Barceló artistarekin. Pintzelen bidez hegan egiten ikasi zuen. Militantea, ekintzailea, zirikatzailea… Osaba Mari zenaren memoria zaindari oraingo egunean.

I've come to look for the painter in the hope that we're in the paintings, and you've drawn me to the Turtzioz cemetery.

Because the mother's older brother is buried here, José María Eletxigerra Matienzo, our uncle Mari. We've still figured out, he doesn't believe it. At home we only knew that he had died on 13 August 1937. We didn't know where or how. The truth is, I don't know how the war entered our valley. My late mother and Uncle Jesus said that Mari should be in Sopuerta or somewhere in Arcentales, but they never knew exactly where he was buried. The two died unknowingly.

Jose Mari didn't know where he was.

My mother didn't say a word about it. It's quite a drama to know that you've been killed, actually, by your brother, and more drama is not knowing where that thing you love, even if it's your bones. The mother remained silent, despite everything. For Uncle Jesus, I knew something. We had a special relationship, we confessed to each other. Obviously, he would tell me the same stories as my uncle. He told me that Franco had killed his brother on 13 August 1937. Nothing else.

But you have known something else.

I went to Aranzadi saying that my uncle had died and disappeared in the war. However, the story begins earlier. A few years ago he attended the Durango Fair, with a stand and two stands, swimming between letters, a collection, civil Gerra in the Basque Country, 1936, and one of the open volumes from par to par: The page was named after José María Eletxigerra Matienzo. "It was our uncle! I told myself. Then I went to Aranzadi, citing the collection, the number and the page of the volume, and the UGT-10 Battalion, also mentioning the Reserve, that is, a copied note of the book.

He was a socialist, Uncle Mari.

I don't know. He was in the UGT battalion, but we don't know if it was for ideology or for fortunation, because, for example, Uncle Jesus made war in the Abellaneda battalion. My mother was also Abertzale, and maybe Jose Mari was too, but I don't know, my mother didn't say anything, I told you. It was taboo. My mother had never skipped the subject. Never. For my uncle, I know how little I'm missing.

Between the chaos of books and letters in the Durango Fair, you read your uncle's name.

It was in 2011. My sister and my brother-in-law were standing next to me, and I remember my sister said, “Wow, he bears the name of our uncle!” and the brother-in-law: “We have it at home, and that encyclopedia!” We went home and read it again. But I didn't insist on that. I thought elsewhere. Two years ago, my nephew informed me of Aranzadi's address and I wrote it by e-mail. They also answered, but Aranzadi's response went to the message box I don't want. Suddenly, her sister said: “Did the Aranzadi answer you?” “No. I'll write them back." I entered the mailbox and the computer told me that I had filled, that the messages had to be erased. The usual puppet! I started erasing, and in messages I didn't want, Aranzadi's. I responded instantly.

What was the Aranzadi response saying?

Here, in this same cemetery. First they told me that José María Eletxigerra Matienzo does not appear anywhere, but José María Etxigerra. I immediately told them that it had to be our uncle, because the dates of death agreed, and our last name has suffered a thousand and a distortion since our great-grandfather was murdered. It is Aretxederra Sanchoyerto, born in Gordexola. But his successors are Etxigerra. Documents also include Aligurra, Adigerra and other pearls read. Obviously, the etxiger is the Eletxiger, our uncle José Mari.

However, there are others buried in the same pit.

“Pedro Aldai, Demetrio Ayuso, Casimiro Mena, José María Etxigerra, Luis Valbuena… On 13 August 1937 dead soldiers buried in grave 62”. In this Turtzioz cemetery, of course. The Aranzadi people told me that I would receive the notification from the Basque Government, and I received it eight days later. I was moved to know where my uncle was buried. “It seems like a lie, I cry for something I have not known in my whole life,” he said. I didn’t know him, but I met him… I met my uncle José Mari through the silences of my mother and the confidences of my uncle Jesus.

You’ve already said, “confidences.”

It was my sweetheart, Uncle Jesusin. Actually, I think it was welcome, that I loved him. For example, don't think about telling my parents that I went to such a demonstration. But my mother guessed something, because that's where it started. “I’ve been told you’ve been at the demonstration…” I'm sure no one told her anything, but the mother guessed what motherhood is. I didn't need to hide with my uncle Jesus. He told him clearly, he told him that he had been at the demonstration. It was he who had confidence in these things.

Your confessions to your uncle, he yours to you.

Yes. He, among other things, sang to me those who sang before the war... “If Sabino Arana comes to your window, treat him with affection that he is Bizkaitarra. If Indalecio Prieto comes to your window, give him two strokes, which is a makeover.” And as for things, my mother hadn't sung that to me, but a month before her death, two months earlier, she started singing to me what my uncle had sung to me. What I had never heard him say. My uncle was a singer. “If you go to Mount Artxanda, don’t think of the Chiribitas, who are strewn with nationalist blood.” Of course, my father didn't sing any of that, because my father was Spanish, but he wasn't Spanish as usual. I wouldn't say that. As far as I am concerned, I did not dedicate myself to Spain, but to patriotism, perhaps a lawyer for the lost causes.

What?

Take the bones out, if possible, and if the law allows it. In that I am making efforts to the Gogora Memory Institute of the Basque Government and to Aranzadi. I would like our uncle not to be in exile, but to rest with the family in the parish of San Miguel de Ahedo, where they were born, made communions, married and died all my maternal ancestors. In Ahedo are all I love: parents, uncle Jesusin, brother, brother-in-law… All.

I assume there will be obstacles, will it not?

There are a lot of mass graves here, and there are also a lot of cuts from the Basque Government. They say no, but the cuts are kept... I, for my part, have told the Aranzadi that I am willing to go where I need to go and do DNA tests. However, I'm reading what tests can be done between family members, and it seems that in order to compare DNA between grandparents and grandchildren, you need males, it's not worth the comparison between male and female. When I read it, I felt like I was hit in my head with the anvil. This bewildered me. I would almost have liked, had I not known that I was in this cemetery of Truces. So close, on the one hand, and so far away, on the other, I'd had a kind of anxiety attack. Another thing is to compare the DNA of the bones of Uncle Mari buried in this mass grave with that of his brother Jesus, although to do so we would have to exhume our uncle Jesusin. If that were the case, I know I couldn't be there, I know.

So yes, would you have peace?

So, bring family members together in this graveyard, invite those who work the memory of the shot, also attend to those of Aranzadi and pay a small tribute. I just want my uncle's bones to be returned to my family's grave. So, it's over. I'm sure when I'm there, my uncle would see it willingly. His mother too, though I wouldn't say so.

We've collected the story in Karrantza. Karrantza is always unknown to us.

There is no talk about Karrantza unless something has been wrong, negative. Little positive is heard of Karrantza. Before it was worse, however… We are forgotten, Karrantza, and Commissions in general. I don't know if it's a matter of transportation, alone. I'm sure so. I have already told him that my mother did not count very much, but I know that, before the war, we had a batzoki next to home, they held rallies, and in them they said they were going to tunnel to connect Karrantza with Balmaseda. On one side of Mount Kolitxa is Karrantza and on the other Balmaseda. What they said at the then rallies was that the quilt had opened and that it had tied to it. Far away! Today they would do so because of the slowness, but it has been more than eighty years since the pre-war rallies and we are still here, for the second time, with a third or fourth category road. From Zalla to Bilbao, yes, but from Zalla to here nothing. The administration has completely forgotten us.

Not attractive in Karrantza? What a beautiful valley!

It's not broken, no. Not enough has been touched. And the spectacular Pozalagua caves are always there. It was wonderful -- it's still wonderful -- but they took a bunch of stones out to make an amphitheater. The stone was cut with a laser. During the summer, a music festival was held at the Bilbao Main Theatre. The lights were channeled in such a way that they produced terrible effects on the stones: one was the head of a ram and the other was the mouth of a deformed being. They made the amphitheatre – something gray, cold – reminds me of the Valley of the Fallen of Franco. Moreover, they opened a day when I was 18 July, so I didn't attend the opening. There are a few dates that have to be kept in memory and inaugurated on 18 July, I find it unpleasant. Anyway, the Pozalagua caves are spectacular.

I was surprised by the present Kontxi Wheat Eletxiger, or Aretxederra. Where is the painter of you?

In places. I would have to wake up a lot of essence of trementine to repaint. When my father died, in 1999, I got naked. Then I took care of my mother, until she died in 2006. So I felt even more empty. And with the empty interior, what are you going to paint? You couldn't paint anything. When my uncle Jesus died, I was also unpainted for a while. Suddenly he took the brushes, started painting and the darkness reigned in my paintings. Renovating a piece of furniture, that's what I do now from time to time, but painting, soiling the canvas, giving it color? No. I've been stuck. Isn't it a crime?

Don't paint artists as a crime.

“Artist” is a great word written in capital letters. I'd like to be an artist, but that's why we have to work a lot, and in my case years ago I haven't worked a lot, a lot, a little bit: nothing. I'm empty, and the vacuum takes up a lot of space. Don't you think so?

“Ez dakit Espainiako gerra zibilak nola jo zuen Karrantzan, baina bonbardaketak izan zirela bai. Gure amaren auzoari senarra hil zioten. Aita mendian ezkutatuta zegoen ‘liberazioa’ etorri zenean, nazionalen ‘okupazioa’, alegia. Osaba Pedro, berdin. Amaren familia abertzalea zen; aitarena, aldiz, eskumakoa. Baina uste dut zintzoen eta gaiztoen artean banatzen zuela mundua, beste barik”.

“Telebista piztu eta ez da memoria historikoa baino ageri. Lehengo batean, Legutio azaldu zen. Berrikiago, 87 urteko agure bat, Avilakoa zen edo Valladolidekoa ez dakit, Espainiakoa behintzat, aita gerran hildakoaren hezurrak hobi komunetik atera eta sendiaren panteoian sartu gura zituena. Agureak zioen, Administrazioak memoria historikoa berreskuratzeko hitza emana duela, baina berari urratsik egiten ez diotela laguntzen”.

“Familiaren zuhaitz genealogikoa egiten ari nintzela, gure benetako deitura azaldu zen: Aretxederra. Eta galdera egin nion neure buruari: ‘Zertan izan behar naiz ni Eletxigerra, Karrantzako arbasoak Aretxederra badira. Garaiko inkisidorearen eskuak oker eman zuen gure izena. Etxigerra, Aligerra, Agigurra…’. Aldatzekotan nintzela, osaba Jesus hil zitzaidan, eta Eletxigerrari eustea erabaki nuen, beraren memorian”.

Elkarrizketa egin eta egunetara, berri ituna du Kontxi Trigo Eletxigerrak. “Hilobia hustekotan ziren Aranzadikoak, baina ezetz, ez datozela esan didate. 1942an atera zituztela guztien hezurrak osabaren hobitik eta alferrik saiatuko direla inoren hezurren bila. Hezurtegira bota zituztela hezurrak eta ez dagoela haien berri jakiterik. Jota nago, hondoa jota!”.

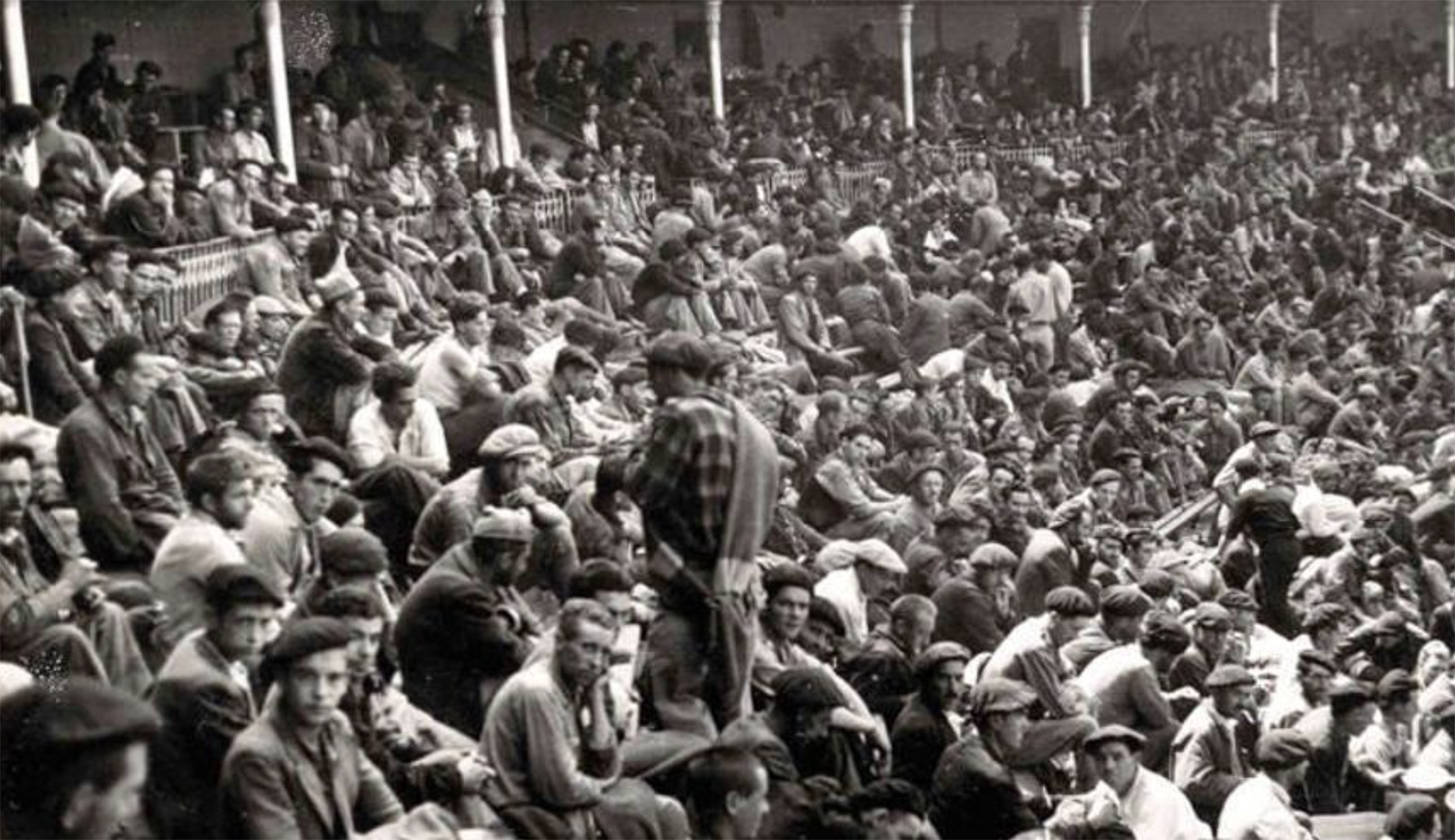

Pamplona, 1939. At the beginning of the year, the bullring in the city was used as a concentration camp by the Francoists. It was officially capable of 3,000 prisoners of war, at a time when there was no front in Navarre, so those locked up there should be regarded as prisoners... [+]

Segundo Hernandez preso anarkistaren senide Lander Garciak hunkituta hitz egin du, Ezkabatik ihes egindako gasteiztarraren gorpuzkinak jasotzerako orduan. Nafarroako Gobernuak egindako urratsa eskertuta, hamarkada luzetan pairatutako isiltasuna salatu du ekitaldian.