The title of Communal Luxury suggests a controversial definition of luxury, beyond the conventional connection between luxury and big capitalists. It brings us to the head of the Italian autonomous movement, how it denounced in the 1970s the pretension of limiting workers’ rights to basic needs, as if luxury was an exclusive right of the major classes; and to denounce it it used slogans like “we have the right to eat caviar”. Is the “communal luxury” proclaimed in Paris in 1871 the first time such a shattering concept of luxury was proclaimed?

I don’t know if the “communal luxury” proclaimed in the Paris Commune was the first manifestation of such a way of understanding breakthrough luxury, without ideas. I don't know if it's especially interesting to try to genealogy the idea. As far as we are concerned, now, at the moment of our present, when, in the name of austerity, we are seeing that the states redistribute wealth to the richest, the important thing is to bring the idea back to fruition. “Communal luxury” was not one of the Comuna’s most audible voices. The term was found in the last sentence of the manifesto signed by the artists and craftsmen of the Community, written at the time when the federation was being formed. It became a kind of prism for me, and observing it, I was able to refrain from some of the Community's key and key ideas. Today, the creator of the term, the poet and decorative artist Eugène Pottier, is known for another reason: At the end of the Bloody Week, the blood was poured into the massacres before it was dried, having written La Internacional. Precisely, Pottier’s contribution to the Federation of Artists has been difficult to see, as the attention of the sages has been obsessed with a much better known comrade and president of the Federation: With Gustave Courbet. For researchers the pathos of Courbet has been attractive because it is considered responsible for the destruction of the Vendôme column, and

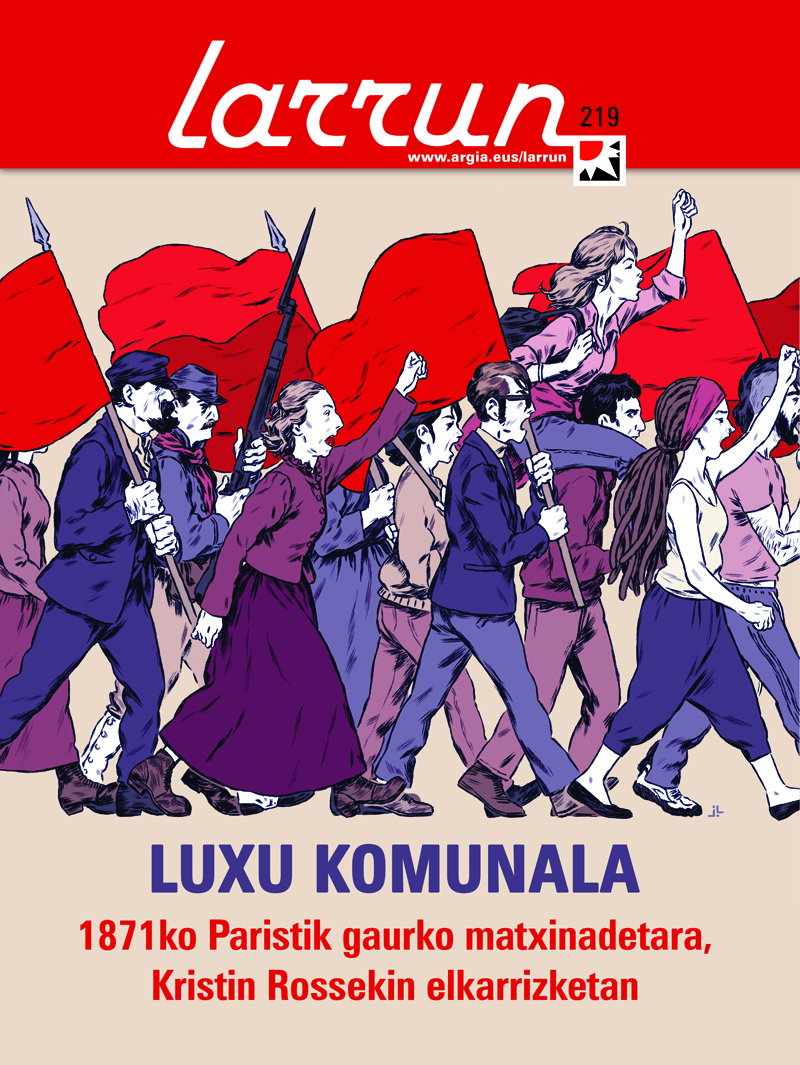

"In the Paris Commune art and beauty leave the private sphere, are fully integrated into everyday life"

Pottier is secluded. But if we reject Courbet – as I do in the book – we see that the hierarchy that was in the middle of the art world was subverted by Pottier and the Federation. This hierarchy gave artists of fine arts a huge privilege, as well as the status and economic advantages that, in the Second Empire, decorative artists, actors and specialized craftsmen could not access these privileges, status and economic security. The Federation’s manifesto concludes with the following sentence: “We will work together to achieve our regeneration, to create communal luxury, the glories of the future and the Universal Republic.” Pottier and other artists with the term “communal luxury” meant “public beauty”: improving the housing environment in cities and towns, the right of all people to live and work in a pleasant environment. That requirement may seem humble, perhaps pure decoration. But, in addition to fully reformulating our relationship with art, it is also a question of reformulating our relations with work, social relations and the living environment. To this end, it is necessary to set in motion the two slogans of the Community: decentralization and participation. Art and beauty leave the private sphere, are fully integrated into everyday life and are not housed in private salons or in obscene nationalist memories. The world is divided into two groups: those who have the luxury of playing with words and images and those who do not. Common luxury will overcome this divide. The actions of the members of the community made it clear that the aesthetic resources and achievements of a society should not be the form of a “deficient Napoleonic tapesty” to recover the words that William Morris used to define the Vendôme column. In other words, the Community meant the total dismantling of the old socially defined artistic customs.

One of the most interesting parts of his last book is the character gallery. You've already mentioned Pottier, but you're also studying other eye-catching characters like Napoles Gaillard, the "shoemaker" and the barricator slug.

The shoemaker Naples Gaillard, or the shoemaker artist, as Gaillard himself said, was reinvented by saying that he was a barricades strategist and architect, building the art and knowledge of the defense of the street, as he had modeled art and his own knowledge about shoes. Communal luxury is, therefore, a way to construct a daily aesthetic process, an act of self-evident emancipation. And from there, we can develop the end of class-based luxury and analyze the new perspective of social wealth that opens up an idea of this kind. The best development of these points of view is seen in the work of William Morris, whose critical analysis of his beauty and useful production is at the center of the transmission of the ideas of the villagers, but also in the useful things that Morris did and in the works on the fact of being an artisan, in which art and usability began to be increasingly separate. In fact, what initially seems to be a decorative requirement of decorative artists requires reinventing wealth and social values, beyond the value of exchange. At the end of the book, in the passages I find in the works of the Community refugees such as Élisée Recruits and Paul Lafargue, what I have called “community luxury” with the words of Pottier becomes the draft of a viable society in ecological terms.

Marx, Recruits, Kropotkin, Morris… All had different starting points to analyze the Community. We see the synthesis work in your book. Should we abandon the segmentation established by the Communist and Anarchist tradition in order to achieve a deeper historical and political analysis of private property and capitalist profit?

Once the bathroom is finished, we see in the works of the community member Recruits, William Morris, Piotr Kropotkin and others that in this demand to flourish beauty in everyday life there are a series of ideas that would today be considered “ecological”, as the ecological sensitivity typical of Morris’s “critical analysis of beauty”, or the importance of self-sufficiency in the Kropotkin region. At the most speculative extremes, “communal luxury” has criteria and values that go beyond the criteria or the system of values given by the markets to decide what society believes. Nature is not considered a resource warehouse: it is estimated by itself.

"In Versailles' propaganda poverty was the only thing that could be shared; Communal Luxury responded to that idea by saying that we all have the right to be part of the best"

The “communal luxury” also had a controversial aspect, which may be useful in our time. The “communal luxury”, as a motto or project, meant the struggle against the concept of mismanagement used by the Versailles: a concept used by the Versailles to explain to the communists who welcomed Paris those who lived in rural areas. To despise the members of the community they used the term partageux, “distributors”. Sharing in Versailles' propaganda was simply sharing poverty. The “communal luxury” responded to an absurd idea: that we all have the right to be part of the best.

In the introduction of the book, he highlights the similarity between the historical context of the Paris Commune and the current political situation. He says that most of the workers who intervened in the Community took longer to seek work than to work. Are we going back to working conditions before the 20th century? Is it a way of questioning the historical teleological and linear narratives of the paid work a revision of the bathroom?

Many people have argued that current and late 19th century working conditions are similar. Alain Diu recently states that as people get tired of theorizing about financial capital or about neoliberalism, the truth is that we have before us all the characteristics of classical capitalism: the world market, the concentration of capital, compulsory imperialism. Thus, when I began to read about the lives of artisans of the late nineteenth century, those who dedicated themselves to the simple unions, the day labourers and the art workers – from these social categories the villagers were born – I would say that I was struck by their true internationality. If we take Eugène Pottier or someone like him – at the time of the Community he had a small workshop where the craftsmen produced everything: lace, painted porcelain, ceramics… – in his study they worked Spanish, Italian and other non-French. As in the current work situation, people sought long distances in search of work and, in addition to going from country to city, it was common to walk between European cities.

The importance you have placed on individuals has brought us some comments from Rancière in The Names of History. Rancière questioned the obsession of some academic historians with the masses, traditionally regarded as “good lessons of historical knowledge”, and asked that attention be paid to subjectivity, taking into account the experience of the individuals who participated in the political struggle. Although most “progressive” historiographies have used the narratives of the masses, does it have the liberating power to investigate individual trajectories?

To see how far an event reaches and its centrifugal consequences, it is necessary to reconstruct the specific phenomenology of this fact, as well as to collect and analyze the voices of the participants of the past. We have to respect the uniqueness of an event, such as the one that the creators of the Community did and said, the one that they thought and said about what they were doing, the words that they used, borrowed, imported, discussed and abandoned, the multiple meanings that they gave to the words and desires that shaped their lives, if we want to imagine that event or struggle in our day by day and consider it a future. I think literary education is an aid, because it highlights the scenario of subjectivization, which is better to start with subjectivity than concepts. I believe that all of this has a benvenistic part, and in that I agree with Rancière: precisely when we say “I” we generate subjectivity; sharing the pseudonym “I” makes possible a profound equality; each one who says that pronoun stays with the full language. With Rancière's hand, I learned to listen to and pay attention to the utterance. According to Rancière, the voices of the workers of the past and those of whom theories about them are later elaborated deserve the same attention if their context and conditions are denaturalized, so that the people of the past, and especially the workers, seem to us subjects and not mere data. To free myself from being merely a representative of their social situation, I organize encounters that are sometimes not expected, tactical restructurings that open up their topicality, or I reconstruct the phenomenology of the event using indirect references. And once positioned, I try to listen to the dynamics that give rise to these encounters. What is at stake is not the search for authenticity, the real worker, the voice of the real community, or the one that really is from here; what is more, the search for how the discourses and projects were built at a given moment and in a given world.

"Scientists and political theorists start with concepts and then use the masses to show the viability of concepts."

Scientists and political theorists start with concepts and then use the masses to show the viability of their concepts or structures. The fact of immersing myself in literature and in the form of a novel has emphasized to me that the personal and concrete decisions about life that are taken in concrete conditions are precisely the essence of historical-geographical change. If we want to show people “historically present”, we cannot start with concepts. Raymond Williams knew this reality well and reflected it in theories, criticisms and novels. And it was no coincidence to use the novels to try to express what he understood as “militant particularism”. I think the only way to imagine today's revolution or freedom is to build or stage the social movements that are now fighting or that were once fighting against specific enemies.

The Karl Marx who describes us, from the time he wrote about the Toilet, is flexible, almost libertarian. He regards the 1871 revolution as a turning point in Marx’s political and intellectual trajectory. Was this a new finding for you? One of the objectives of his book is to recover a Marx beyond Marxism?

I think what happened in Paris in the spring of 1871 had to move Marx completely. On a personal level, I knew some of the wrestlers on the street, and some of them were friends and friends. On a political-existential level, for the first time he saw people pushing a life that was not capitalist, in a situation in which it was actually occurring. For the first time, he had the opportunity to see how people behaved as a life-owner, and not as a wage slave. And I think Raya Dunayevskaya is right when he says that that actual experience made Marx a complete break from the concept of theory. At that point in her work, she went from researching the history of theory to researching the history of class struggle, and that was her true theory. And that's what mattered to him after the toilet.

For me, that idea wasn't new -- in fact, in my first book, The Emergence of Social Space, I said the same thing in another way, analyzing some of Marx's early works, like the criticism of Hegel's 1843 state doctrine. In this book I highlighted Marx’s clash with that “invention of the unknown” – that is, of the Community – and how through this he discovered that freedom depends on political forms that by themselves are liberating. I sometimes call that his “moment of understanding Audre Lorde.” The poet Audre Lorde was a Jamaican American saying that the house of the owner cannot be dismantled with the utensils of its owner. The “operational existence” of the Community made it clear to Marx that the working class cannot use the bureaucratic forms of the State to carry out its purposes. It has to find ways that by themselves are liberating.

"The Community made it clear to Marx that the working class cannot use the bureaucratic forms of the State to carry out its purposes"

As I was writing The Emergence of Social Space, a book taught me a lot, and I still consider it one of the most important works of Marxist theory. Late Marx and the Russian Road (late Marx and Russian route), edited by Teodor Shanin. The arguments presented in this book, those of Dunayevskaya or my working ideas on the Community, have recently been captured and developed by some interested in Marxism outside Europe such as Kevin Anderson and Harry Harootunan. In my opinion, this line of research is fruitful in the field of Marxism studies, much more productive than detailed studies of theories of values that are too academic and seemingly unfinished.

THE PAST CAN BE UNDERSTOOD DIFFERENTLY

The Community, or May 1968, tends to be seen as a “failed revolution,” precisely because they did not gain power or were unable to maintain it. With your books we give you another image, that is, that the achievement of the Community and of May 1968 was already there, in the “operational existence” you mention, using the term Marx. In order to assess the political movements of the past, should we revalidate the taking of power and the logic of failure/victory?

Yes, the logic of failure/triumph that you have mentioned does not offer us much of the movements of the past, but it is a very persistent logic. I recently spoke to Alain Diu, who regarded the Community as an example of failure. I wanted to ask him what the Toilet would look like, which would triumph at that time. It's always been hard for me to know what success is and what failure is. In English we have an expression: “How many swallows do we need to be spring?” In my opinion, there is no other event in history that has generated as many specialists as the Paris Commune in the post-factual analysis, it is a paradise for rear seat drivers, as I say to you. Why didn't the villagers take Versailles? Why didn't they have better military organization? Why did they waste time (assuming they were aware that the Commune was about to end and that the time was precious) in the debate in the City Hall? Why didn't they get the bank's money? The endless comments and analyses of the common raise questions such as this one or enumerate the “errors” of the villagers – who also make those who love the memory of the common. It is terrible for me to see how indelible that desire is: the desire to teach something to the past, or the use of the “failures” of the past to teach us something (and that in essence is the same). With Diu, I tried several ways to avoid the pedagogical paradigm I used with respect to the past. I told him that for those who lived in the Community a real sense of freedom and a network of solidarity had emerged. I referred to the ideas that I had opened up and that we can now take into account thanks to the imaginative nature of the event. I talked about the need to clearly distinguish the toilet and the state crime that had ended it. And despite all this, Médials, the host of the debate, published the interview with the title “The Lessons of the Toilet.”

"Many progressive thoughts continue to function as if there were a project of goals to be achieved, as if it was possible to define exactly those goals"

All of this, in my opinion, shows that many progressive thoughts on freedom work as if there is still a draft of objectives to be achieved, as if it were possible to define exactly those objectives and to measure objectively whether or not they have been achieved, using traditional standards or those that have been drawn up in 2017. Of course, it gives us great pleasure to give ourselves the ability to decide at a particular moment what is possible, impossible, soon or too late to do so, if it is obsolete or unfeasible. But when we take that attitude, experimental aspects of art and politics are lost. I have had to leave behind all the remains of that balance sheet logic that I have described in order to analyse the Community as a laboratory of political invention and to see the potential that the common people, working together, are putting in place to manage their affairs.

The book refers to a conceptual change that occurred before the 1871 rebellion: in the popular meetings held in clubs and associations, people were called “citizens”. You say that those small details – which according to traditional historiography happened long before the starting point of the Community – had profound connotations with society. Can the Community be understood without these new subjectivities that did not fall into the traditional category of the middle class?

Whether fictitious or not, the most important framework of a narrative is its beginning or end. The opening of a chronological framework for narrating an event is effective in transforming the way of understanding “what happened”: it broadens the social or geographic point of view and offers us a panorama of broader experiences, such as regions or participants that we did not know or considered before. Starting from another place, we can see a new aspect of the development of the liberating movement and say something about it, “denaturalizes” all the myths that have been fixed around the beginning of an event. As a matter of fact, the Paris Commune presents us with a special challenge: As Claude Roy once said, there is no other event, so rigid and independent, that it fulfils so exactly the three characteristics of the tragic genre: place, time and action. Seventy-two days inside the city walls ended in a bloody and fiery cataclysm. The State torpedly tried to disarm the workers of Paris, regressed and proclaimed the Community. In other words, the temporality of the State had been interrupted and, after seventy-two days, thousands of workers had been slaughtered, resumed.

He mentioned the “temporality of the state”. Could I develop that idea a little bit more?

The problem with the narrative that's usually told is that it starts with the state and ends with the state. Finally, it becomes a state narrative. For me, what the states do is interesting, but I find it more interesting not to start with the traditional principle, on March 18 and that of the guns, and instead to start with the working meetings that flourished in the city at the end of the Empire and recreate the phenomenology of those meetings: they met for the first time in Parisian and non-Parisian neighborhood groups, old militants of 1848 and young members of the International, From the experience of these meetings, from the new relationships in which the principles of collaboration and cooperation were tested, the desire arose to create a common human being or something. The structure and customs of the meetings were the embryo or the silhouette of the Community, so the community member Arthur Arnould stated that the Community already existed when he saw how Paris organized its business. From that moment on, the history of the Community is reported and its causality emerges from the situation of war against a foreign force: earlier it was said that material deficiencies, food for zoological animals and frustrated patriotism led workers to rebellion. Now, the war in Prussia becomes a simple moment of war into a much more important political and temporal fact, the ongoing civil war. And as war and patriotism disappear from sight, we can begin to see the internationalist intentions of the working culture of the time, which were the support of a social community.

In the book May ‘68 and Its Afterlives, it also seems to us that you are trying to question the traditional historical narratives of May ’68.

When I started the study on May 1968 in France, many French people told me that the violence that happened in Paris at the end of the Algerian war in the early 1960s had nothing to do with the student revolt that happened a few years later. For many people, between the tumultuous beginning of the 1960s and the relaxation of the late decade, there was a chasm that generated this kind of journalistic topic: “The year 1968 was a lightning bolt that came out of a quiet sky.” Instead of starting with the students, I decided to start with the first mass rebellion in the 1960s, the Algerian demonstration against curfew on October 17, 1961. From there, viable follow-up was achieved among students and activists – minority, yes, but important – previous national freedom efforts and anti-colonialist efforts, as this succession was previously invisible by topics such as “boring France”. Of course, the advantage of starting is that the framework comes out of a narrow national narrative – and with global events such as that of 1968 we have to act like this.

"The problem with many political narratives is that they start with the state and end with the state. They become state narratives."

But the finals are also important. For me, where to start and where to end a narrative is not based on a mere chronology, not even on a narrow historicist issue in terms of dates; for me, the question is the influence they have on heritage and political transmissions and the debates about them – and all of them are part of the political struggle. I'm going to give you an example. In 2008, several narratives were published to commemorate the events of 1968, some of which, like Artières and Zancarini-Fournelena, began to incorporate the events of Algeria into the history of 1968. But I was surprised by the length of time they had proposed. The 1968 years, according to them, ended in 1981, when François Mitterrand won the elections. Why use the State’s criteria – “politique des politiciens” – to mark the end of a radical succession? Once again, state narration demands primacy – it does not support other kinds of expressions or its temporary claim. And historians give up. I am convinced that the years of May ended before that, with the great movements of Lip and Larzac poorly analyzed, and with the shift towards a melancholic and opportunistic movement against totalitarianism, launched by those who repented of 68 and by the New Philosophers, often the same people. It is important to see that the 1968 offensive ended there, so that the anti-capitalist movements that emerged from 1995 are more clearly seen, and Larzac, for example, became a useful resource or file for movements like Notre-Dame-des-Landes. Historians decided in 1968 to delve into the counter-revolution that took place in the mid-1970s – the demarxification of France and the “rise of the left against totalitarianism” – without making it clear that it was a counter-revolution, which gives us little hope with the books we will have in 2018.

You cast doubt on the fact that the Community enters the history of the French republic. On the contrary, it highlights the international image of the villagers: Universal Republic. Do you see similarities with the M15 movement or with Occupy Wall Street? These movements were limited to national environments, but they were fighting for global change. Who, in your view, has best followed the true international character of the Community?

I find local movements very interesting, with specific and limited geographical positions in a territory. It may be a paradox, but I think those limited movements that have to do with reality have the most international and centrifugal consequences, precisely because they have to do with reality. Their relationship with people's daily lives gives them authority and ability to reverb. David Harvey has interesting views on this topic: he tells us that geographic struggles generate a dialectic of the “this or the other” type, which has little to do with the transcendental dialectic of Hegelianism. They demand a political, existential decision. The problem is not theoretical, there is only one enemy to fight. The construction of an airport in rural areas. If you're going to dig a 90-kilometer tunnel in the Alps. I have just finished a translation and a preface to a book by a group of ZAD from Notre-Dame-des-Landes, on their struggle and that of the NoTAV from northern Italy, the movement against the TAV that is to be built through the Alps. The ZAD, as you will know, is a kind of bathing going on: it is precisely the occupation of the airport that is to be built in western France and the fight that currently lasts longer in France. Last spring, the inhabitants of the ZAD invited me to come to him to discuss the follow-up and break-ups of the 1871 rebellion and what is currently happening at Notre-Dame-des-Landes. We were very well thinking about the idea of “common luxury” in the context of what they are trying to create in the ZAD. I believe that these very limited movements (the ZAD has only 1,650 hectares) are very international, both because of the exemplary struggles they have with the states, and because of the new form of political intelligence that is emerging. They have lasted over time – and this did not happen in other cases, like Taksim, Occupy or Madrid, all of them in urban areas, not by chance.

He mentioned the contemporary movements taking place in rural areas and the efforts of the villagers of Paris to establish relations with the camp workers are of great importance in his book. We are currently seeing the development of the “new extreme right” discourse, Front National attracts the working classes and the Alt-Right of the EE.UU. uses the discourse against the “liberal elites of cities”. Is it urgent to work strategies against the division between the rural environment and the city?

I am asked whether the speeches of the “new extreme right” such as the Front National and the Alt-Right of the EE.UU. They were born in the countryside, but I would like to underline one thing that has just appeared: a new rural life, very alternative and fighting, at least in France. This rural life is opposed to industrial agriculture, to the destruction of rural areas, to the privatisation of water and other resources, and to the State, together with large multinational companies, developing infrastructure projects of all kinds (public-private agreements). When in America they deal with “gigantic, tax and absurd” infrastructure projects, it is usually the indigenous people who carry out these actions, such as the Standing Rock and other previous movements, such as Brazil against the Xingu River dam or Chiapas itself. In Europe, on the other hand, there are many who participate in these movements – nuns, anarchist blocks… – and learn to work together, creating an effective coalition. The duration of these movements is one of the most striking features. Immersed in a concrete struggle, they feed on the values shared by the occupants, who are especially heterogeneous. The maintenance of coalitions requires a kind of reciprocal and special relationship, which occurs only in specific places and over time. The practical aspect of everyday life - building buildings, animal care, planting crops, library organization - does not generate a biased vision that we can expect. The ZAD is a very social experiment, and although it is a form of secession with the State, or perhaps for that reason, it does not turn its back on society. The daily life actions, the awareness of daily life and the full responsibility of it create an experimental center, a point of view, a commitment of active perception with all the components of the world, where the small scale allows us to rethink what we have among all and, in doing so, we analyze the world from beyond with a new critical attention. In my opinion, a movement like the ZAD, which is by the way a very feminist movement, is a sign of a change in political sensitivity that begins at the end of the century and is already underway. In these years, people began to realize that the effort to change social inequalities had to be reconciled with another factor: caring for the ecological and living foundations of life. The widespread denial of capitalism to the anguish generated by the intervention of life, not only of young people, is a reflection of the widespread denial of the ZAD. But it also suggests that, from now on, our relationships with living beings in important political movements will be at the center of those movements. In this sense, in the middle of the last century, the living conditions of the planet became a new and undeniable meaning of political struggle.

THE POSTREBEL THEORY

The Commune of Paris and May 1968 are seemingly distant facts, but the links you make between them are very convincing. How is it possible to produce those echoes beyond history?

My first research work, influenced by the interest in dealing with issues related to the cultural movement of Rimbaud and the Paris Commune, arises from the perspective of May 1968, in which I read thinkers like Henri Lefebvre and Jacques Rancière, who remain fundamental in my thinking. But it has to be borne in mind that my thinking about literature, history and historical processes is a production of the 1970s. Born in the post-1968 era, at the time of conception of “bottom-up history”. So I came across the first works by Rancière and those by Révoltes logiques magazine, and I translated some. The journal Révoltes logiques was not the only one who tried to write the story in a different way – at that time many historiographical experiments were carried out, and on some of them I wrote in May ‘68 and its Afterlives. Precisely, one of the main conclusions of 1968 was that there was a great debate about who should write the story, who had the right preparation to write the story and how it should be written. And then the non-professional historians appeared. In France they were called “historiens sauvages”, in the United States they were called “the history from below”, in the United Kingdom they were called History Workshop Journal...

Were these radical contributions of historiography the basis of your work?

In my opinion – and I would say yes in many others – these experiments were a kind of solidarity with that recent political past, the possibility of continuing with a type of work, even if it did not listen to a university, or even sometimes despised that work at a university. Therefore, when asking about the connections between the Community and May 1968, we must first take into account the possibilities of framing them so that these connections can be shown. Most historians – those who understand their work as a guild and, in many cases, those who understand historical research in a very narrow way – do not allow that point of view. Therefore, to me, the lack of formal education as a historian was an advantage. And so, I was very lucky to learn at the Santa Cruz “experimental” Campus of the University of California, which was a product of 1968. The students planted vegetables in the cafe and there were no notes. And at that time -- Vietnam, the bombing of Cambodia -- many of us were involved in popular militancy activities.

All of this doesn't look much like the university we know today. What was the school like?

Thanks to innovative methods, the Santa Cruz School attracted a wide range of multidisciplinary professors, including N.O. Classicist Brown, Freudomarxist and sometimes his friend and competitor Herbert Marcuse; schizophrenia theorist Gregory Bateson; urban theorist Reyner Banham; and others. The most interesting teachers, by far, were Marxists or, at least, materialists who knew the Marxist theory well. Seen from the cage or the carapace of current academic standards, authentic farms for specialization and opportunism, that group was, in comparison, a very lively group. Brown, in particular, stressed the importance of the theme of desire being in the forefront of all Marxist analyses, and introduced me to a number of thinkers who would help me to illuminate that path, such as Walter Benjamin, Ernst Bloch, William Morris, Blake, Charles Olsen and style poets.

But graduate studies were something else. I studied at Yale University, and at that time hyper-intellectualized textual formalism was at the center of the lessons, so it was hard for me to find my way, to see what was important. Fortunately, Fredric Jameson went into college and helped me regain the continuation of the education I had received and teach Lefebvre's work. Using my case as an example, what I want to describe is the strength and fragility of political transmission, especially in counter-revolutionary times. In this regard, it would be very interesting to study in France a figure like Daniel Bensaid.

In the time he described, the theory of history was radically redefined. But in France, the 1970s was, at the same time, the time to rewrite the past and not in a liberating way.

When I began my research on Rimbaud and the Comuna, the cultural history that I found in Révoltes logiques was especially exciting for me, as it dismantled the literary approach and the sociological determinism of Marxism: these stereotypical expressions also appear in the works of the most progressive social scientists and political activists, both before and now. In the journal Révoltes logiques, the base and the superstructure did not correspond openly; there were hardly any model reports about the good workers, and the field of class relations was fraught with misunderstandings. It seemed that work and life were much more complicated, contradictory and complex than we wanted.

"From the beginning, my bet was that we could see better the customs of the villagers through poetry than through the speeches of the social scientists"

But at the time after 1968, when I was starting, those who were activists soon became famous and began to give up their previous participation in the movement, it was a certain process of distancing that would re-write the entire French revolutionary tradition in a revisionist way. They were rewriting as if the French Revolution had not happened, or they became the American Revolution, with the intention of creating a genealogy that would explain the recognition of neoliberalism in the early 1970s. The guardians of the 1968 official memory met with historians such as François Furet, who wanted to spread that terror permeates all the impulses in favor of social change, and that this whole matter of revolutionary history has nothing but the purpose of achieving the power of the “major thinkers”. Revolutionary events were concealed and their status as events was denied, prioritizing continuity and homogeneity over the unpredictability and contingency. Historians of the furet type and similar not only devoted themselves to it: the most important historiography school in the postwar period, the Annales school, also dedicated itself to it. I believe that the political context in which it was darkened left a very clear question uncovered: “What’s going on, for what future?” I was drawn to the moments when those so-called anti-motalitarian leftists disappeared. The Paris Commons, for example, or 1968 itself. Working on Arthur Rimbaud and the culture of the Community, I thought he was addressing a field of thought and action that he opened in 1968. My bet was that we could see better the customs of the villagers through poetry than through the discourse of social scientists, and that we could better illuminate the work of Arthur Rimbaud in the context created by the workers, the scientists, the beggars and the geographers, than in the context created by other poets. Refracted through the culture of Common Poetry, and through poetry, I had the opportunity to attack the post-structuralist zepo that united literary research back then.

In some cases, this “solidarity between times” had a very concrete form; Lefebvre, for example, wrote a great deal about the Community. In other cases, it was produced without direct relationship with the original sources. In this regard, Communal Luxury mentions the special relationship between Recruits and Bernard Lambert.

Bernard Lambert was an important person in Western France. He was a self-taught baserritarra and in 1971 he wrote a classic text: Les Paysans dans la lutte de classes (Peasants in class struggle). Lambert had never made that connection with Recruits, and I don't think I'd ever read it. I myself made the connection between these two works, and so I argued that both the workers and the peasants were on the same side as the opposite of capitalist modernity and that they used the same rhetorical strategy. I refer to the “solidarity between the times” that they mention, that the years between the Community and the 1970s were linked to the beginnings of a new sensibility, carried out by people like Élisée Reclus, to which we must call ecological, although at that time we do not use words of this kind. This kind of eco-thinking got deep asleep and didn't wake up again until a hundred years later, when the important American thinker of ecology and grooming Murray Bookchin wrote about it. Even in that case I don't know if Bookchin had studied or recognized Recruits' work. The most striking thing is that Recruits wrote at the time about the issue, since no one thought about agricultural issues. Very few Europeans visited the West of the United States and, like Recruits, saw it underway.

Through the reading of his books, it can be concluded that the main insurrection movements provoke critical thinking. Is this situation repeated throughout history?

I am not surprised that great theoretical blooms occur after great social revolts and revolutions – as in 1968 or in the Paris Commune. And it is not uncommon for the theoretical lines of thought that appear at the moment to resemble, or even overlap, creating echo systems; all this is to be expected, since acts of this kind, as Sartre wrote about the Vietnam War, “open up the field of possibilities.” At that time the State regresses, its political temporality is broken or interrupted, and we begin to see the existence of ways of organizing material life that escape the logic of benefits. Debates then take place that are outside the scope of experts and that deal with our common interests. And when this happens, people get back to the experience of owning their own life, rather than being wage slaves.

Macron made his press conference on 12 June to read the elections to Parliament. Above all, it has had the time to repeat that the right end and the left end are both landers exactly the same. Although he has criticised one and the other, he has opened up ideas of charm of the... [+]

I will spare you too many explanations and details, the esteemed reader who looked at this text. The issue is very simple. I'll talk about you, about me, about all of us. I am going to refer to the amazing travellers of this boat that is still floating without direction and ever... [+]

The crisis on the left jumps to Latin America. Until recently, progressive governments could be found on almost the entire map of the region. But things are changing in recent months. The three presidential elections marked a turning point: Daniel Noboa won in Ecuador, Javier... [+]

“And what is the weather she perceives for Thursday?” I asked the feminist militant that she was organizing the A30 strike. “The truth is that lately I’ve had my head in a conflict at school,” he replied with a serious face.

The Vox Solidarity party union called for a... [+]

When analyzing the history of social movements and protest, the most abundant studies are those of the Contemporary Age. Sources are more abundant, conflicts are more abundant, and researchers also share the view of the world of research. That is, as we pass through the sieve of... [+]

French and Spanish leftist parties and movements have a different relationship with the concept of nation and with nationalism. This completely conditions the relationship with the Basque nationalists. But why? The key to the theme lies in the different processes of creation of... [+]

Euskal Herrian "paradigma iraultzaile berria" zabaldu eta garatu nahi duen Kimua ekimen herritarra zenbait herritan aurkezpen bira osatzen ari da. Hala Bedi irratian Kimuako kide batekin hitz egin dute proiektuaren inguruan gehiago jakiteko.