"We don't have to have Diogenes syndrome with the Basque Country."

- Young and practical philologist, professor of teaching, researcher of ancient texts and demystifier of Basque myths.

1987, Iruñea

Filologoa, Nafarroako Unibertsitate Publikoko Filologia eta Hizkuntzen didaktika departamentuko irakaslea, Fontes Linguae Vasconum aldizkariko zuzendari berria, Nafar Ateneoko euskara eleduna, Aziti Bihia filologo eta hizkuntzalari gazteen taldeko fundatzailea, Monumenta Linguae Vasconum taldeko kidea eta euskal testu zaharren maitale eta aztertzaile nekaezina.

You're working on training future teachers. What is your work at the Public University of Navarra?

My students are studying to be Kindergarten and Elementary teachers. With the Euskaldunes we try to improve the linguistic communicative resources, while the Castilian speakers give the Basque in the first course from scratch, as well as issues related to the history of the Basque Country. Many have contact with the Basque Country for the first time. The concepts that are acquired about Euskera in these years will be very important for them and their future students.

Some students complain that the first year of Basque learning has been compulsory and then disappears from the program. We abandon the students. I think we should offer it as an optional one.

On the other hand, from the next course we will open the Euskera line in the Master's Degree in Secondary Education Faculty offered by the UPNA

There was a time when there was a lot of concern about the Basque level of the profesores.La preoccupation a hundred years ago was that the Basque was not worth home, and now I begin to notice a

contrary trend, as many of our students, especially those who have been Euskaldunizado in the school, have a problem with the Basque home and street. The students of the Vascophony area are also very much transformed when they come to Pamplona.

What to do?They are

used to learning grammar and should work more in the communication field, but the university does not offer too many possibilities. I'm telling you very clearly about my experience: I developed Euskera in college, but not just in the classroom. I have always learned Euskera since I was young, but I have really learned to speak in Euskera in the Basque countries; with the lekeitiarras, the Segura, the baztandarras…

The 18-25 period is a very important time, since the Basque language goes from being the language of the adolescent to the adult. Suddenly, language has to occupy other spaces, and that's the key. It is often observed that young people who have undergone compulsory Basque studies are Castilian or Spanish speakers when they attend higher education in Spanish or are going to study outside and back.

There is also concern about the quality of Euskera among young people. What do you think?

From home, the Basque of a Basque is not the same as that of a child who speaks Model D, but the new Basque must not be criminalised. Everyone has developed a number of skills. It is a question of seeking balance. Many times we take care of everything, we keep everything, without thinking too much for what we want. We cannot turn the world into a museum. You can't save everything. It's OK to pick up the names of the tools in the farmhouse, but we'd have to consider to what extent our students would have to learn. We have to measure the strength and money we put into these kinds of things and for what purpose. We shouldn't have Diogenes syndrome with the Basque.

I wrote an article with the philologist Juan José Zubiri on children's language. Child language, the way adults talk to children, is pretty rich in Basque and has some special characteristics, but it's being lost. We set out for what purpose to save it, for what purpose. The conclusion we draw is that child language is not an obstacle to learning the language, while it performs certain functions. We believe that it can serve in the Euskaldunberris families of the city to bring the Euskera from the school home and recover the Euskera that the parents learned in the school, with great emotional value. Very good materials have been created, such as Xaldun Kortin, in Navarra.

.jpg)

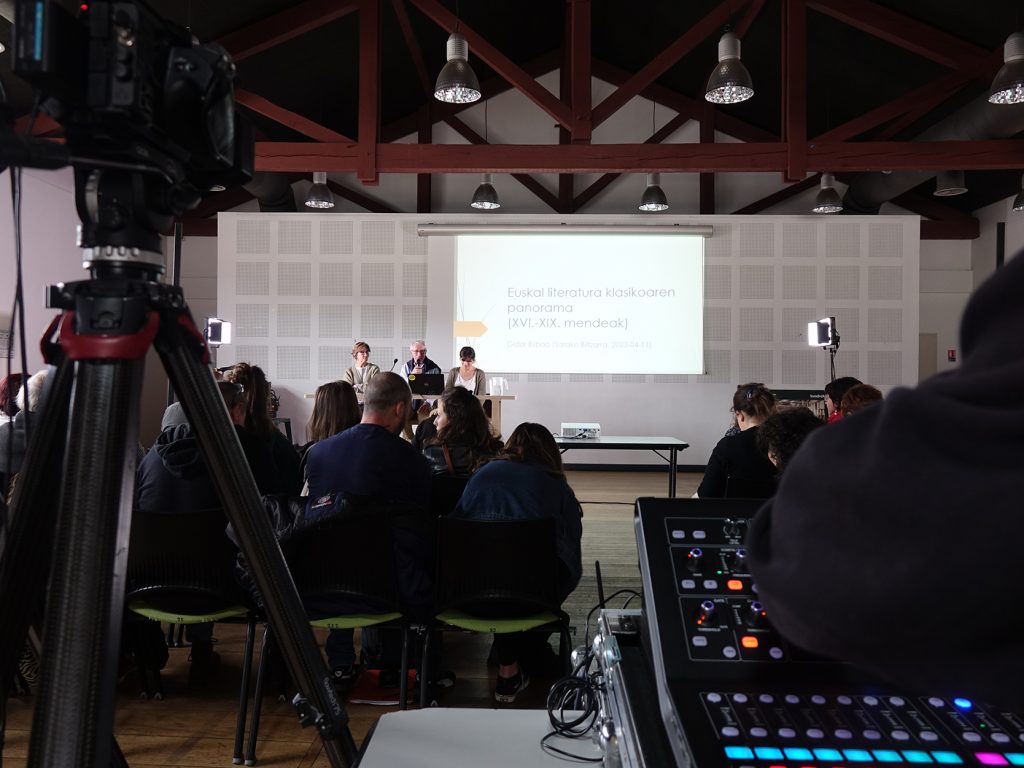

What did you create for the group of philologists Aziti Bihia?

There are few philologists and linguists who investigate the history of the Basque Country, but at the UPV/EHU a nice generation of young people emerged around the faculty of Vitoria-Gasteiz, and we thought it was better to meet. Teamwork allows us to work other ways, help us, bring together the knowledge of all and all, and serves us to do projects within and outside the university environment, as well as for mutual comfort. We believe it is very important to socialize the bases and methodologies of linguistics and philology developed in the university.

Many times demystifying myths about Euskera. What myths are they? The

idea of romanticism is that Euskera is an isolated and strange language, and I have tried to put everything in its literary, political and social context, in various courses and conferences. History shows that the Basques have always been in contact with other cultures. For example, people remember the legend of Gartxot: the Basques isolated in a corner between mountains. That is why I like to put next to the literary image of that zarauztarra the beautiful baroque altarpiece of the church of Ezcároz or the dances of Muskilda. The Basques have been there until yesterday and yet have not lived behind the scenes of the time, quite the opposite. These peoples have become small and isolated in the last centuries, but they have had great relations and social movements ever since, and they still have much to say in the social structure of Navarra.

He has also referred to the Gené isolation tico.Se says that Euskera

has no kinship, but the only thing it means is that by applying a scientific and rigorous comparative methodology, with the quality and quantity of data we have, at the moment we have not been able to associate Euskera with another language. This does not mean that you have never had a relative, but that at every moment we do not have enough reliable data to find our relatives by applying the scientific method. Today, there are more than a hundred languages isolated in the world, so it's not uncommon.

It is also often heard that Euskera has rare characteristics, but the “rare” things of Euskera can also be found in other languages. The ergative, for example, is very common in the world, for example in Australian languages. Putting the verb at the end of the sentence is also a very normal thing in the world; perhaps the most normal thing. In this sense, most languages of the world are like Spanish (verb in the center) or as Euskera (verb in the end). The point is that so far we have had a Europazentrist vision, among other things, because we have had very little data and descriptions about the languages of the world. If, instead of comparing Euskera with the European languages, we compare it with those of the rest of the world, we will see that it has very few things that are nothing more than its own.

For example?

Typologically, the rich txistus system is quite peculiar. Today we have six, although it hasn't always been like this: x, s, z, tx, tz, ts.

And is it the oldest language in Europe?The origin of languages, of any language, is lost in time, because it is a continuum in which the language constantly changes and we cannot say when that language has been

invented; it always comes from something else that existed before, changing and changing until we reach the current situation. I ask the students what is the oldest language, the Basque language or the Spanish, and they answer that it is usually the Basque language, because the Spanish comes from the Latin language, but one is as old as the other. What happens is that there is a terminological fraud: it is a trap to call Basque what was done five hundred, two thousand or five thousand years ago, as if it had always been the same language, and to Castilian, on the contrary, to say romance, Latin Indo-European or whatever.

It is the Aziti Bihia that you found two years ago in Denmark a copy of the doctrine of the Franciscan Esteve Materra of the seventeenth century (and at the moment only one). Your best-known job, you adjust.

It is a very interesting text, as it is the first text published in the classical laboratory of 1617. The first edition was lost; since the second edition, that of 1623, only one copy is kept in Oxford and in the Basque Country, the copies of research were not of very high quality; it deserved philological attention. It was a boom. After two months of constant media presence, we were left with a sour sweet taste. The attention of the people and we were content with it, but sometimes we saw that the interest of the people and the media did not correspond to ours. People were focusing on discovery, not on text, but on luck, but there is an infrastructure and an investment in the university environment; the development of Basque philology has been tremendous in recent decades, and trained researchers are working on it. They know what they're looking for, how to look for it, and they have the knowledge and the basis to bring their philological value to the text.

What has been for you the oldest text you have analysed?

It's not an easy answer. If I were to mention one, I would refer precisely to one that I have not worked: The manuscript by Joan Pérez de Lazarraga is being analyzed in depth for various reasons by colleagues from the research group Monumint Linguae Vasconum. It is an Alavese text with few old texts. On the subject, it is not a religious text, but a poetry written or copied by a humanist teenager. In the Basque Country that it uses, there are many interesting features, some unknown until then, and others not witnessed in that area or at that time. In addition, as noble was poetry in Basque, it has shown us a rather unknown socio-linguistic situation.

.jpg)

And how is the economic value of the old texts determined?

We don't get into that. We analyze the text and contextualize it, but economic value is based on market criteria. In 1995, for example, the Navarre Savings Fund purchased a copy of the Leizarraga New Testament of 1571 for 30,600,000 pesetas, almost 184,000 euros, and in 2008 Euskaltzaindia purchased another copy for 24,000 euros. Why that difference? The causes are above philology.

What do you have now in your hands? The

work never ends. A handwritten doctrine related to Lizarraga de Elcano has recently appeared in Roncal, and I would like to analyse it. Moreover, I have just arrived from Paris, because as a history of Navarros and Basques handwritten in French by the gentleman Belako de Maule in the 18th century has come to my hands, I wanted to see the works of this author in the National Library of France. The texts of the gentleman are a great treasure for history, ethnography, and as far as I am concerned, for the Basque Country, which also offers passages. Recently a small doctrine has appeared written in Zarauz by the otsagabarra Garralda de Ciria in 1895, which together with others we are studying.

He has just taken over the direction of Fontes Linguae Vasconum. What are the main challenges?

Fontes' challenge is twofold. On the one hand, following the line it has since its creation, it intends to be the nest of ancient texts in Basque. On the other hand, to the extent that Basque linguistics is a university discipline, we must adjust our journal to the strict requirements that the current university system imposes on international journals and researchers obliged to publish in them, if we want to attract researchers to our journal, which is not easy in a field as small as the Basque one. But we have to try.

What is the photo blog?

I do philological tourism, I'm pretty geek and I take pictures of places and things that have to do with the history of the Basque Country. I wanted to share all those images with people and put them on the blog. There are, for example, an 18th-century crucis of Iturmendi with texts in Basque; the tomb of Captain Duvoisin, collaborator of Prince Bonaparte; or that of Prince Bonaparte. I put the places on the map so that people can easily find them and the photos are available to everyone.

“Euskalkiekiko izugarrizko begirunea izan dugu eta altxorrak dira, baina ulertu behar dugu hiztunen arteko harremana galtzen denean sortzen direla, eta hizkuntza berez batzen dela hiztunak elkartzean. Euskara bereziki azken 200 urtetan dialektalizatu da. Euskara, hizkuntza guztiak bezala, eta euskalkiak bezala, aldatzen ari dira etengabe: gauzak sortzen ditu, uzten, edo beste leku batetik hartzen. Adibidez, Erronkaribarreko eta Zaraitzuko erakuslearen k- (kau(r), kori, kura) forma, kontu berri samarra dela susmoa hartzen hasiak gara. XVI. mendeko adibide apurretan ez da horren arrastorik agertzen, esate baterako. Horregatik ez naiz gehiegi kezkatzen hizkuntza aldatzeaz. Ondo entzuten bada Iruñeko gazteen artean, eta ez ongi, aldaketa onartu behar dugu. Behintzat euskaraz ari dira”.

Antton Kurutxarri, Euskararen Erakunde Publikoko presidente ordearen hitzetan, Jean Marc Huart Bordeleko Akademiako errektore berriak euskararen gaia "ondo menderatzen du"

You may not know who Donald Berwick is, or why I mention him in the title of the article. The same is true, it is evident, for most of those who are participating in the current Health Pact. They don’t know what Berwick’s Triple Objective is, much less the Quadruple... [+]

Is it important to use a language correctly? To what extent is it so necessary to master grammar or to have a broad vocabulary? I’ve always heard the importance of language, but after thinking about it, I came to a conclusion. Thinking often involves this; reaching some... [+]

Adolescents and young people, throughout their academic career, will receive guidance on everything and the profession for studies that will help them more than once. They should be offered guidance, as they are often full of doubts whenever they need to make important... [+]

Maiatzaren 17an Erriberako lehenengo Euskararen Eguna eginen da Arguedasen, sortu berri den eta eskualdeko hamaika elkarte eta eragile biltzen dituen Erriberan Euskaraz sareak antolatuta

Ansorena´tar Joseba Eneko.

Edonori orto zer den galdetuz gero, goizaldea erantzungo, D´Artagnanen mosketero laguna edo ipurtzuloa, agian. Baina orto- aurrizkiak zuzen adierazten du eta maiz erabiltzen dugu: ortodoxia, ortopedia, ortodontzia... Orduan (datorrena... [+]

We have had to endure another attack on our language by the Department of Education of the Government of Navarre; we have been forced to make an anti-Basque change in the PAI program. In recent years, by law, new Model D schools have had to introduce the PAI program and have had... [+]

"Ask for your turn and we'll join you," the willing and cheerful announcer who speaks from the studios tells the young correspondent who walks through the streets of Bilbao. The presenter immediately addressed the audience. "In the meantime, we are going to Pamplona..." They opened... [+]